From the turn of the century and immediately after the war. Completed in 1895 by architect Franz Schwechten as a 'gift' to Germans from Kaiser Wilhelm II, serving as a memorial to his grandfather Wilhelm I. Its bells, made from bronze from guns captured in the Franco-Prussian War, fell victim to material shortages during the war when four of the five bells were removed from the tower on January 7, 1943 and melted down again for war purposes. Only the smallest bell remained for the congregation. When the church was destroyed, this bell was badly damaged and in 1949 it was delivered to the Schilling bell foundry in Apolda, where it was once cast. The church itself was substantially destroyed during a bombing raid in 1943 when, during the night of November 22-23 the church building caught fire during a British air raid, causing the roof structure over the nave to collapse and the top of the main tower to snap off. The Nazi leadership promised the community that after the war the destroyed Memorial Church would be rebuilt just as large and magnificent. In contrast, the victorious powers of the Second World War found this plan relatively difficult; the building also reflected Wilhelmine-German national pride. In the post-war period the ruins were left to decay for the time being. It wasn't until 1956 that demolition of the choir, which was in danger of collapsing, began. Several different options for the church's redevelopment were considered, including the construction of a new church made from glass in the old church's ruins, and also its complete demolition and replacement with a new structure. Eventually it was decided to leave the ruined tower as a memorial to the futility of war, (or specifically to remember Germans killed in British retaliatory bombings) and create a new church around it with a breathtakingly ugly building next to it for some reason. The new church was consecrated on May 25, 1962 - the same day as the new Coventry Cathedral. On Breitscheidplatz, its eastern

terminus, the landmark Kaiser-Wilhelm-Gedächtniskirche stands quiet

and dignified amidst the roar. Allied bombs left only the husk of the west

tower intact; it now contains the Gedenkhalle whose

original ceiling mosaics and marble reliefs hint at the church’s pre-war

opulence. The adjacent octagonal hall of worship, added in 1961, has

intensely midnight-blue windows and a giant golden Jesus floating above

the altar. On November 14, 1940 the Germans obliterated the

city centre of Coventry including its Gothic cathedral from the 14th

and 15th century. Already in January 1941 the people of Coventry held

mass again in the burnt out church, having rebuilt an altar from

rubble, and using charcoaled beams as the holy cross and made a cross

with three hand-forged nails they found in the rubble. On January

7, 1989, on the occasion of the inauguration of the Memorial Hall, the

Nail Cross of Coventry was given to Kaiser-Wilhelm-Gedächtniskirche as a gift where it remains as a reminder of peace and reconciliation.

July 19, 1945 and standing in front and inside, next to the Cross of Coventry which has a prominent place in the Memorial Hall of Gedächtniskirche. The former entrance hall of the old building was converted into a room commemorating the events and destruction of the Second World War on January 7, 1987 on the occasion of Berlin's 750th anniversary. One of the central exhibits here is the Coventry Cross of Nails as a symbol of reconciliation. The nails from which it was formed are from burnt roof beams of Coventry Cathedral , which was destroyed in German air raids on November 14, 1940 and also deliberately preserved as a ruin.

At the dedication ceremony on September 1, 1895, the eve of the Day of Sedan, and in front in 2024. In fact, at the time of its dedication the entrance hall in the lower section had not yet been completed; that part of the church was not opened and consecrated until February 22, 1906.

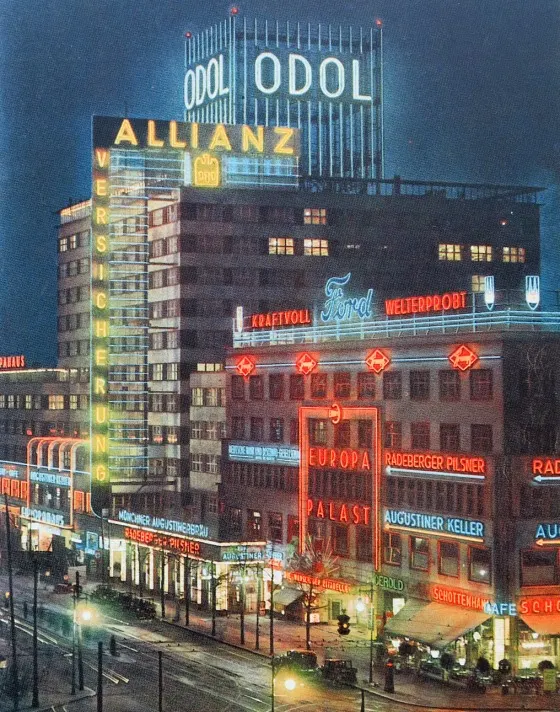

Goebbels, writing the article “Rund um die Gedächtniskirche,” for the January 23, 1928 edition of Der Angriff, described the area in which

Comparing the scene during the Christmas market of 1929 only two months after the Wall Street Crash and 2016 after yet another example of terror with the church providing the latest backdrop for Merkel-era terrorism caused the summary acceptance of a million immigrants, many men of fighting age, she allowed to enter the country, mostly without any screening or background checks. In this case the perpetrator was Anis Amri, an asylum seeker from Tunisia. It wasn't until four days after he had hijacked an HGV and killed the driver before turning lights off and driving the stolen lorry into shoppers at a Christmas market at 40mph killing twelve and injuring 48 that he was finally killed in a shootout with police near Milan in Italy. On December 19, 2016 at 20:02 the terrorist ploughed a len truck through the Christmas market, causing the deadliest terrorist attack in Germany since an attack at Oktoberfest in Munich in 1980, which killed thirteen people and injured 211 others. The truck came from the direction of Hardenbergstraße, drove about 160 feet through the market, and destroyed several stalls before turning back onto Budapester Straße and coming to a stop level with the Kaiser Wilhelm Memorial Church. Several witnesses saw the driver leave the truck and flee towards Tiergarten. One witness, Łukasz Urban, ran after him. He was found dead in the passenger seat of the truck cab having been stabbed and shot in the head with a small-calibre firearm.

At the dedication ceremony on September 1, 1895, the eve of the Day of Sedan, and in front in 2024. In fact, at the time of its dedication the entrance hall in the lower section had not yet been completed; that part of the church was not opened and consecrated until February 22, 1906.

Goebbels, writing the article “Rund um die Gedächtniskirche,” for the January 23, 1928 edition of Der Angriff, described the area in which

[i]n the middle of this turmoil of the metropolis the Gedächtniskirche stretches its narrow steeples up into the grey evening. It is alien in this noisy life. Like an anachronism left behind, it mourns between the cafés and cabarets, condescends to the automobiles humming around its stony body, and calmly announces the hour to the sin of corruption. Walking around it are many people who perhaps have never gazed up at its towers. There is the snobby flaneur in a fur coat and patent leather; the worldly lady, garçon from head to toe with a monocle and smoking cigarette, taps on high heels across its walkways and disappears into one of the thousands of abodes of delirium and drugs that cast their screaming lights seductively into the evening air. That is Berlin West: The heart turned to stone of this city. Here in the niches and corners of cafés, in the cabarets and bars, in the Soviet theatres and mezzanines, the spirit of the asphalt democracy is piled high. Here the politics of sixty-million diligent Germans is conducted. Here one gives and receives the latest market and theatre tips. Here one trades in politics, pictures, stocks, love, film, theatre, government, and the general welfare. The Gedächtniskirche is never lonely. Day plunges suddenly into night and night becomes day without there having been a moment of silence around it. The eternal repetition of corruption and decay, of failing ingenuity and genuine creative power, of inner emptiness and despair, with the patina of a Zeitgeist sunk to the level of the most repulsive pseudoculture: that is what parades its essence, what does its mischief all around the Gedächtniskirche.Return of Evil to Merkel's Germany

Comparing the scene during the Christmas market of 1929 only two months after the Wall Street Crash and 2016 after yet another example of terror with the church providing the latest backdrop for Merkel-era terrorism caused the summary acceptance of a million immigrants, many men of fighting age, she allowed to enter the country, mostly without any screening or background checks. In this case the perpetrator was Anis Amri, an asylum seeker from Tunisia. It wasn't until four days after he had hijacked an HGV and killed the driver before turning lights off and driving the stolen lorry into shoppers at a Christmas market at 40mph killing twelve and injuring 48 that he was finally killed in a shootout with police near Milan in Italy. On December 19, 2016 at 20:02 the terrorist ploughed a len truck through the Christmas market, causing the deadliest terrorist attack in Germany since an attack at Oktoberfest in Munich in 1980, which killed thirteen people and injured 211 others. The truck came from the direction of Hardenbergstraße, drove about 160 feet through the market, and destroyed several stalls before turning back onto Budapester Straße and coming to a stop level with the Kaiser Wilhelm Memorial Church. Several witnesses saw the driver leave the truck and flee towards Tiergarten. One witness, Łukasz Urban, ran after him. He was found dead in the passenger seat of the truck cab having been stabbed and shot in the head with a small-calibre firearm.

Plötzensee Gaol (Strafgefängnis Plötzensee)

The eight killed in this way were Robert Bernardis, Albrecht von Hagen, Paul von Hase, Erich Hoepner, Friedrich Karl Klausing, Helmuth Stieff, Erwin von Witzleben and Peter Graf Yorck von Wartenburg. Hundreds more would follow, both at Plotzensee and throughout the Reich where persons distantly connected to the plotters and various miscellaneous resistance figures were swept up in the purge.

The prison was built between 1869 and 1879 near Lake Plötzensee in Charlottenburg off Saatwinkler Damm. During the Nazi era, over 2,500 people were executed including members of the Red Orchestra (Rote Kapelle), Kreisau Circle (those accused of the plot against Hitler's life on 20 July 1944 at the Wolfsschanze), Czechoslovakian resistance fighters, and various others declared to be 'enemies of the state' by the Volksgerichtshof ("People's Court").  At the entrance has been built this memorial wall "[t]o the Victims of Hitler's Dictatorship of the Years 1933–1945." Kershaw describes in Hitler:

At the entrance has been built this memorial wall "[t]o the Victims of Hitler's Dictatorship of the Years 1933–1945." Kershaw describes in Hitler:

Once the verdicts had been pronounced, the condemned men were taken off, many of them to Plötzensee Prison in Berlin. On Hitler’s instructions they were denied any last rites or pastoral care (though this callous order was at least partially bypassed in practice). The normal mode of execution for civilian capital offences in the Third Reich was beheading. But Hitler had reportedly ordered that he wanted those behind the conspiracy of 20 July 1944 ‘hanged, hung up like meat- carcasses’. In the small, single-storey execution room, with whitewashed walls, divided by a black curtain, hooks, indeed like meat-hooks, had been placed on a rail just below the ceiling. Usually, the only light in the room came from two windows, dimly revealing a frequently used guillotine. Now, however, certainly for the first groups of conspirators being led to their doom, the executions were to be filmed and photographed, and the macabre scene was illuminated with bright lights, like a film studio. On a small table in the corner of the room stood a table with a bottle of cognac – for the executioners, not to steady the nerves of the victims. The condemned men were led in, handcuffed and wearing prison trousers. There were no last words, no comfort from a priest or pastor; nothing but the black humour of the hangman. Eye-witness accounts speak of the steadfastness and dignity of those executed. The hanging was carried out within twenty seconds of the prisoner entering the room. Death was not, however, immediate. Sometimes it came quickly; in other cases, the agony was slow – lasting more than twenty minutes. In an added gratuitous obscenity, some of the condemned men had their trousers pulled down by their executioners before they died. And all the time the camera whirred. The photographs and grisly film were taken to Führer Headquarters. Speer later reported seeing a pile of such photographs lying on Hitler’s map-table when he visited the Wolf’s Lair on 18 August. ϟϟ-men and some civilians, he added, went into a viewing of the executions in the cinema that evening, though they were not joined by any members of the Wehrmacht. Whether Hitler saw the film of the executions is uncertain; the testimony is contradictory.

Once inside Plötzensee, the prisoners were allowed only time to change into prison garb. One by one, in accordance with prison drill procedures, they crossed the courtyard in wooden shoes, under the ever-present gaze of a camera, and entered the execution chamber through a black curtain. Here, too, a camera recorded their every step as they arrived and were led to the back of the chamber to stand under hooks attached to a girder running across the ceiling. Floodlights brilliantly illuminated the scene. A few observers were standing around: the public prosecutor, prison officials, photographers. The executioners removed the prisoners handcuffs, placed short, thin nooses around their necks, and stripped them to the waist. At a signal, they hoisted each man aloft and let him down on the tightened noose, slowly in some cases, more quickly in others. Before the prisoner's death throes were over, his trousers were ripped off him. Every detail was recorded on film, from the first wild struggle for breath to the final twitches.

Once inside Plötzensee, the prisoners were allowed only time to change into prison garb. One by one, in accordance with prison drill procedures, they crossed the courtyard in wooden shoes, under the ever-present gaze of a camera, and entered the execution chamber through a black curtain. Here, too, a camera recorded their every step as they arrived and were led to the back of the chamber to stand under hooks attached to a girder running across the ceiling. Floodlights brilliantly illuminated the scene. A few observers were standing around: the public prosecutor, prison officials, photographers. The executioners removed the prisoners handcuffs, placed short, thin nooses around their necks, and stripped them to the waist. At a signal, they hoisted each man aloft and let him down on the tightened noose, slowly in some cases, more quickly in others. Before the prisoner's death throes were over, his trousers were ripped off him. Every detail was recorded on film, from the first wild struggle for breath to the final twitches.Hitler had already "eagerly devoured" the arrest reports, information on new groups of suspects, and the statements recorded by interrogators. Now, on the very night of the first trials and executions, the film of the proceedings arrived at the Wolf's Lair for the amusement of the Führer and his guests. The putsch, he announced to his assembled retinue, was "perhaps the best thing that could have happened for our future." He could not get enough of watching his foes go to their doom. Days later, photographs of the condemned men dangling from hooks still lay about the great map table in his bunker. As his horizons shrank on all sides, Hitler took great satisfaction from this, his last great triumph.Fest (302-3) Plotting Hitler's Death: The Story of the German Resistance

The execution chamber at Plötzensee Prison showing the guillotine that was used to behead most victims until the sheer number of executions during the Third Reich made it impractical. Today there is a memorial inside the gaol commemorating those executed by the Nazis, dedicated on September 14, 1952. All that remains now is the execution shed, a small brick building with two rooms, where the victims were either hanged or beheaded. Cadavers of the condemned would be delivered to the anatomical institute at Humboldt University to be used for dissection under supervision of Professor Stieve.

(translated by Pete26 at Axis History Forum)

The severed head fell into the basket, eyes wide open. Because the body was not strapped to the guillotine bench, the body could move freely after decapitation. The torso reared up, the legs twitched and threw off the wooden clogs. The blood spurted out of the severed neck in a high arc into the drain.

In this place of execution, everything represented the power and glory of the Nazi state. The executioner and his three assistants in black suits, the prosecutor and pastor in back robes, the clerks in green uniforms, the prison doctor in a white coat, the guests in uniform. On the table were two candles in tall candle holders. At this place of death ruled law and order, and each step was determined by the protocol. For the guests there were tickets and a note: "At the execution site the German greeting [Hitler salute] is to be avoided." The condemned were expected to behave according to the protocol too: "Calm and composed." Only rarely did the condemned fight back. According to protestant pastor Hermann Schrader, "I remember no one who has cried, screamed, or resisted."

In this place of execution, everything represented the power and glory of the Nazi state. The executioner and his three assistants in black suits, the prosecutor and pastor in back robes, the clerks in green uniforms, the prison doctor in a white coat, the guests in uniform. On the table were two candles in tall candle holders. At this place of death ruled law and order, and each step was determined by the protocol. For the guests there were tickets and a note: "At the execution site the German greeting [Hitler salute] is to be avoided." The condemned were expected to behave according to the protocol too: "Calm and composed." Only rarely did the condemned fight back. According to protestant pastor Hermann Schrader, "I remember no one who has cried, screamed, or resisted."From the command "Executioner, do your duty" to "Mr Prosecutor, the verdict is enforced", it took only twenty to 25 seconds in peacetime, and during the war only seven or even four seconds, to carry out the execution. For every execution, an A5 form had to be filled out. Many of the over three thousand executed here are left with not even a photograph. The oldest victim was a worker 83 years old, the youngest just seventeen. Forty one couples were executed here and they were not even allowed to say last words to each other. Mothers, who gave birth whilst in prison, were not spared. A total of 250 women were beheaded.

An old shoemaker cut the hair of the condemned short the night before the execution to expose the neck for the blade. The old man did his duty without emotion and with some kind of satisfaction. For each police sergeant who led the condemned from the cell block to the execution shed, there was a reward of eight cigarettes per person. The executioner's assistants would deposit two corpses into one coffin; each twenty centimetres shorter than usual and sprinkled with sawdust to soak up the blood. The guillotine was eventually dismantled and delivered to the administration of the Soviet occupation zone shortly after the war.

The repositioning was then carried out at a distance of 33 metres between the columned halls, which made it possible to pass through the two 14.50 metre wide carriageways and the four meter wide median. In order to achieve an architectural unity of the new bridge with the gate, the parapets were made of tuff stone and the bridge structure was clad with sandstone. Bernhard Schaede, the architect of the gate, was involved in this work as a manager. Street lights designed by Speer were installed along the entire east-west axis for the street lighting which are still seen in places today. There was a further need for electricity from the lighting of the festive decorations of the street, which were taken into account during the expansion. Nine underground network and switching stations were installed to supply these systems with power. One of them was built in the immediate vicinity of the northern portico of the Charlottenburg Gate. The access to the maintenance staircase in the gate also served as access to this network and switching station. As part of the festive decoration of the street, the Nazis repurposed the gate as a flag holder. Oversized swastika flags were hung between the pillars and across the road on the front sides of the columned halls on appropriate occasions. Above shows Canadian troops from Les Fusiliers Mont-Royal on July 14, 1945 under the pompous five metre high bronze statue of Friedrich I which had accompanied his wife Sophie Charlotte on the other side of the gate. On the stone pillars facing the street were originally two bronze sculptures created by the sculptor Georg Wrba, the loss of which has damaged the overall appearance of the building since 1945. The northern figure represented a woman riding a stag with a veil blowing over her head; the southern figure shows a man riding a horse with a shield and sword in his hand. The Zentralblatt der Bauverwaltung commented on the two bronze sculptures with the words "It is not easy to untangle these intertwined bodies, and it is even more difficult to find their meaning"

The repositioning was then carried out at a distance of 33 metres between the columned halls, which made it possible to pass through the two 14.50 metre wide carriageways and the four meter wide median. In order to achieve an architectural unity of the new bridge with the gate, the parapets were made of tuff stone and the bridge structure was clad with sandstone. Bernhard Schaede, the architect of the gate, was involved in this work as a manager. Street lights designed by Speer were installed along the entire east-west axis for the street lighting which are still seen in places today. There was a further need for electricity from the lighting of the festive decorations of the street, which were taken into account during the expansion. Nine underground network and switching stations were installed to supply these systems with power. One of them was built in the immediate vicinity of the northern portico of the Charlottenburg Gate. The access to the maintenance staircase in the gate also served as access to this network and switching station. As part of the festive decoration of the street, the Nazis repurposed the gate as a flag holder. Oversized swastika flags were hung between the pillars and across the road on the front sides of the columned halls on appropriate occasions. Above shows Canadian troops from Les Fusiliers Mont-Royal on July 14, 1945 under the pompous five metre high bronze statue of Friedrich I which had accompanied his wife Sophie Charlotte on the other side of the gate. On the stone pillars facing the street were originally two bronze sculptures created by the sculptor Georg Wrba, the loss of which has damaged the overall appearance of the building since 1945. The northern figure represented a woman riding a stag with a veil blowing over her head; the southern figure shows a man riding a horse with a shield and sword in his hand. The Zentralblatt der Bauverwaltung commented on the two bronze sculptures with the words "It is not easy to untangle these intertwined bodies, and it is even more difficult to find their meaning"

Haus der Jugend

The Haus der Jugend at Reinickendorfer Straße 55 on Nauener Platz in Berlin-Wedding. It was constructed between 1928 and 1930 as the Gemeindeschule der jüdischen Gemeinde zu Berlin, a Jewish community school financed by the Berlin Jewish community and designed by the Jewish architect Alexander Beer. The school opened in April 1930 and initially housed a primary school, a secondary modern school, and administrative offices of the Jewish community. By 1933 it accommodated approximately 450 pupils. Under the Nazis the school continued to operate under increasing restrictions imposed by the Nuremberg Laws and successive anti-Jewish decrees. From 1935 it functioned as one of the few remaining Jewish schools in Berlin because Jewish children were progressively excluded from state schools. In 1937 the Reichsvertretung der Juden in Deutschland established a teacher-training institute within the building. By 1938 the complex served multiple purposes: classrooms, a kindergarten, youth club rooms, and accommodation for Jewish youth organisations such as the Ring-Bund jüdischer Jugend and the Kameraden. Following Kristallnacht in 1938 the Gestapo confiscated the building. The school was closed immediately and the pupils dispersed to other remaining Jewish institutions.  In early 1939 the property was transferred to the Reichsvereinigung der Juden in Deutschland under duress and then sold at a fraction of its value to the city of Berlin in 1940. From 1939 the building was repurposed by the Hitlerjugend and the Nationalsozialistische Volkswohlfahrt. It officially became the Kreisheim der HJ-Bann 184 Wedding and was renamed Haus der Jugend. Extensive internal alterations were carried out in 1939-1940 including the removal of Jewish symbols and the installation of Hitler Youth facilities such as meeting halls, a gymnasium, and sleeping quarters.During the war years the Haus der Jugend served as a regional headquarters for Hitlerjugend Bann 184 which covered Berlin-Wedding and parts of Reinickendorf. It housed training courses, ideological instruction, and accommodation for HJ leaders. The building also functioned as a collection and distribution point for the NSV winter relief campaigns and as temporary quarters for evacuated Hitler Youth units from bombed areas. Air-raid shelter facilities were added in the basement. The structure suffered moderate bomb damage in 1943-1945 but remained usable. After May 1945 Soviet and later British occupation authorities used it briefly before it was returned to the reconstituted Jewish community in 1946. From 1947 it again served Jewish educational and youth purposes until the community sold it in the 1980s.

In early 1939 the property was transferred to the Reichsvereinigung der Juden in Deutschland under duress and then sold at a fraction of its value to the city of Berlin in 1940. From 1939 the building was repurposed by the Hitlerjugend and the Nationalsozialistische Volkswohlfahrt. It officially became the Kreisheim der HJ-Bann 184 Wedding and was renamed Haus der Jugend. Extensive internal alterations were carried out in 1939-1940 including the removal of Jewish symbols and the installation of Hitler Youth facilities such as meeting halls, a gymnasium, and sleeping quarters.During the war years the Haus der Jugend served as a regional headquarters for Hitlerjugend Bann 184 which covered Berlin-Wedding and parts of Reinickendorf. It housed training courses, ideological instruction, and accommodation for HJ leaders. The building also functioned as a collection and distribution point for the NSV winter relief campaigns and as temporary quarters for evacuated Hitler Youth units from bombed areas. Air-raid shelter facilities were added in the basement. The structure suffered moderate bomb damage in 1943-1945 but remained usable. After May 1945 Soviet and later British occupation authorities used it briefly before it was returned to the reconstituted Jewish community in 1946. From 1947 it again served Jewish educational and youth purposes until the community sold it in the 1980s.

In early 1939 the property was transferred to the Reichsvereinigung der Juden in Deutschland under duress and then sold at a fraction of its value to the city of Berlin in 1940. From 1939 the building was repurposed by the Hitlerjugend and the Nationalsozialistische Volkswohlfahrt. It officially became the Kreisheim der HJ-Bann 184 Wedding and was renamed Haus der Jugend. Extensive internal alterations were carried out in 1939-1940 including the removal of Jewish symbols and the installation of Hitler Youth facilities such as meeting halls, a gymnasium, and sleeping quarters.During the war years the Haus der Jugend served as a regional headquarters for Hitlerjugend Bann 184 which covered Berlin-Wedding and parts of Reinickendorf. It housed training courses, ideological instruction, and accommodation for HJ leaders. The building also functioned as a collection and distribution point for the NSV winter relief campaigns and as temporary quarters for evacuated Hitler Youth units from bombed areas. Air-raid shelter facilities were added in the basement. The structure suffered moderate bomb damage in 1943-1945 but remained usable. After May 1945 Soviet and later British occupation authorities used it briefly before it was returned to the reconstituted Jewish community in 1946. From 1947 it again served Jewish educational and youth purposes until the community sold it in the 1980s.

In early 1939 the property was transferred to the Reichsvereinigung der Juden in Deutschland under duress and then sold at a fraction of its value to the city of Berlin in 1940. From 1939 the building was repurposed by the Hitlerjugend and the Nationalsozialistische Volkswohlfahrt. It officially became the Kreisheim der HJ-Bann 184 Wedding and was renamed Haus der Jugend. Extensive internal alterations were carried out in 1939-1940 including the removal of Jewish symbols and the installation of Hitler Youth facilities such as meeting halls, a gymnasium, and sleeping quarters.During the war years the Haus der Jugend served as a regional headquarters for Hitlerjugend Bann 184 which covered Berlin-Wedding and parts of Reinickendorf. It housed training courses, ideological instruction, and accommodation for HJ leaders. The building also functioned as a collection and distribution point for the NSV winter relief campaigns and as temporary quarters for evacuated Hitler Youth units from bombed areas. Air-raid shelter facilities were added in the basement. The structure suffered moderate bomb damage in 1943-1945 but remained usable. After May 1945 Soviet and later British occupation authorities used it briefly before it was returned to the reconstituted Jewish community in 1946. From 1947 it again served Jewish educational and youth purposes until the community sold it in the 1980s.  The former Haus der Reichsjugendführung, originally opened in 1928 as a department store, became under the Nazis the headquarters for the Reich Youth Leadership, established after the Nazi seizure of power in March 1933, in order to guarantee the ideological orientation of the German youth and thus to secure the future rule of the Nazis. he Reich Youth Leader stood at the head of the Hitler Youth. Baldur von Schirach was the first Reich Youth Leader, eventually replaced on August 8, 1940 by his deputy Artur Axmann. Tasks of the Reich Youth Leadership were the Gleichschaltung the existing youth associations, the political and ideological indoctrination of German youth with the aim of educating convinced National Socialists and the control and suppression of deviant from the Nazi ideal youth cultures. After the seizure of power, the Nazi regime tolerated no other youth associations in addition to the Hitler Youth. The other groups were dissolved, unless they volunteered. One of the largest of these groups was the "Bündische Jugend" - a collective term for youth groups influenced by the youth movement in the 1920s. The young people came mainly from bourgeois classes. Common to the groups was the idea of self-determination ("youth educates youth"), as well as joint actions such as hiking and camping, playing music and singing. A strong bond to home and nature showed in particular the two dominant directions, the Wandervogelbewegung and the Boy Scouts.

The former Haus der Reichsjugendführung, originally opened in 1928 as a department store, became under the Nazis the headquarters for the Reich Youth Leadership, established after the Nazi seizure of power in March 1933, in order to guarantee the ideological orientation of the German youth and thus to secure the future rule of the Nazis. he Reich Youth Leader stood at the head of the Hitler Youth. Baldur von Schirach was the first Reich Youth Leader, eventually replaced on August 8, 1940 by his deputy Artur Axmann. Tasks of the Reich Youth Leadership were the Gleichschaltung the existing youth associations, the political and ideological indoctrination of German youth with the aim of educating convinced National Socialists and the control and suppression of deviant from the Nazi ideal youth cultures. After the seizure of power, the Nazi regime tolerated no other youth associations in addition to the Hitler Youth. The other groups were dissolved, unless they volunteered. One of the largest of these groups was the "Bündische Jugend" - a collective term for youth groups influenced by the youth movement in the 1920s. The young people came mainly from bourgeois classes. Common to the groups was the idea of self-determination ("youth educates youth"), as well as joint actions such as hiking and camping, playing music and singing. A strong bond to home and nature showed in particular the two dominant directions, the Wandervogelbewegung and the Boy Scouts.

After the war the building was seized by the Communist regime until 1956 where it was then used to house

the Communist Party archives and the Central Committee’s Historical

Institution. Renamed the Zentralausschusses der SPD and nationalised, after the forced union of the political parties KPD and SED in 1946 it was turned into the main quarter of the SED party leadership and from then on called the "Haus der Einheit”- note the portrait of Stalin above the entrance. The first and only President of East Germany, Wilhelm Pieck, as well as Prime Minister Otto Grotewohl had their offices here. This was also where the Stalinist party model for the SED was worked on, where the party was “cleansed” from critics and where politically justified death penalties were pronounced against regime opponents. Another event defining the history of this building were the protests on June 17 in 1953, when protesters from the national uprising gathered mainly here as well as in front of the “Haus der Ministerien.” After German reunification the building was legally

returned to the descendents of its original owners, but has remained

derelict until now where it is has been renamed Soho House, located at Torstraße 1 on the corner of Prenzlauer Allee. Ironically given its 'socialist' past, it's now a private members’ club with forty bedrooms set over eight floors along with a spa and gym, rooftop pool, restaurants, bars, a screening room and a private dining area.

Children playing on a Pz.kpfw.-Bodenturm Panther turret in 1945 from Hans-Christian Adam's Berlin: Portrait of a City and the same building behind today.

Children playing on a Pz.kpfw.-Bodenturm Panther turret in 1945 from Hans-Christian Adam's Berlin: Portrait of a City and the same building behind today.

As the the war inevitably began to turn against the Germans, the Wehrmacht desperately came to the decision to employ use Panther tank turrets as improvised fortifications as seen here, even though the Panther itself was still being produced as the main medium German battle tank. Initially, these turrets used were from standard production models leaving the Allies to conclude that either "the [Panther] chassis is not too satisfactory or that its production has been hindered by our air attacks." As it turned out this was in fact now a standard German fortification. Although the first installations captured by the Allies mounted standard Panther tank turrets (primarily from the older Ausf. D, but also the later Ausf. A turret) purpose built turrets were also encountered. These turrets were simplified versions of the standard production model with the main visible difference being that they were fitted with a flat hatch rather than a cupola added to the turret roof being constructed using a 40 mm plate as opposed to 16 mm given that the emplaced turrets were more vulnerable to artillery fire. Once the turret had opened fire it had effectively highlighted its location to enemy artillery and therefore needed to be able to withstand the inevitable barrage. German tests showed that the additional armour meant that the turret could withstand a hit from a 150 mm artillery shell. Such fortifications were not improvisations but specially developed as seen from the fact that they were mounted on purpose built shelters.

Located on Hermannplatz, where Kreuzberg meets Neukolln, the Karstadt department store was one of the most revolutionary buildings to be constructed in Berlin before the war. Opened in 1929 as Europe's biggest department store over nine floors with a total of around 72,000 square metres of usable space, it had its own underground station and 56 metre-high art deco twin towers that were strikingly reminiscent of a Manhattan skyscraper. Wartime bombs left little of its original grandeur intact, yet it was promptly rebuilt and is still one of Berlin's most popular department stores. The ϟϟ used its twin towers as an observation post as four separate Soviet armies entered the city. In the Battle of Berlin, Hermannplatz became a focal point of the final battles of the war. Cornelius Ryan would write how, in the afternoon of April 25, “the huge department store blew up. The ϟϟ blew it up in order not to let the Russian hands fall into the hands of the 29 million marks it had stored in the cellar. There were several deaths."

Only one wing of the original building survives, on the southwest corner as seen in the photo above.

Only one wing of the original building survives, on the southwest corner as seen in the photo above.

Petty crime skyrocketed as the inhabitants of Berlin turned to looting as a survival strategy. One of the looters' targets was the huge Karstadt department store on Hermannplatz. Thousands of people crammed into Karstadt, grabbing everything in sight but especially food and warm clothing. The store supervisors eventually let them get away with whatever food they could find, though they tried to prevent them taking anything else. Later, after driving the remaining civilians out, the ϟϟ, rumoured to have had 29 million marks' worth of supplies in the basement, dynamited the store to prevent the Russians from appropriating itscontents.

Bahm (140-1) Berlin 1945 - The Final Reckoning

Standing at the site in 2011

There has been a dramatic account of the looting of the Karstadt department store in the Hermannplatz, where queuing shoppers had been blown to pieces during the first artillery bombardment on 21 April. According to this story, ϟϟ troops allowed civilians to take what they wanted before they blew the place up. The explosion was said to have killed many over-eager looters. But in fact when the ϟϟ Nordland Division took over the store several days later, they did not want to blow it up. They needed Karstadt's twin towers as observation posts to watch the Soviet advance on Neuk6lln and the Tempelhof aerodrome [...] The twin towers of the Karstadt department store provided excellent observation posts for watching the advance of four Soviet armies - the 5th Shock Army from Treptow Park, the 8th Guards Army and the 1st Guards Tank Army from Neukolln and Konev's 3rd Guards Tank Army from Mariendorf.Beevor:

A

Sturmgeschütz III (StuG III), Germany's most-produced armoured fighting

vehicle during the war, waiting on Invalidenstrasse for the Red Army to

arrive.

An IS-2 heavy tank (the IS for “Iosif Stalin”), dubbed the “Tank of the Victory," at Proskauerstraße during the advance down Frankfurterallee- a triumphal arch would later be set up in Frankfurterallee which was later to become one of the showpieces of Stalinist

architecture. The IS-2 was the first production model

and mounted a long-barrel 122-mm gun and was in service until the late

1960s. The tank saw combat late in the war in small numbers, notably against Tiger I, Tiger II tanks and Elefant tank destroyers. The Battle of Berlin saw scores of IS-2s employed to destroying entire buildings thanks to their powerful HE rounds in support of the 7th separate Guards (104th, 105th and 106th tank regiments), the 11th Heavy Tank Brigade’s 334th Regiment, the 351st, 396th, 394th regiments from various units and the 362nd and 399th regiments from the 1st Guards Tank Army, the 347th from the 2nd Guards Tank Army, all part of the 1st Belorussian Front, and the 383rd and 384th regiments of the 3rd Guards Tank Army (1st Ukrainian front). They would be tactically arranged into small units of five IS-2s supported by a company of assault infantry, including sappers and flame-throwers. Despite its sloped 4.72 inch thick frontal armour at an angle of 60° and massive 14.8 inch main gun, the shortcuts taken would prove real issues on the long run, starting with the gun itself, slow to reload and with bulky two-piece naval ammunition. Perhaps it shouldn't be too surprising that the Red Army suffered a a considerable

loss of tanks by this stage of the war despite it being the "finishing

blow". Leaving out the frontier battles which are otherwise misleading

given the high numbers of abandoned vehicles, the Battle of Berlin was

in terms of tank losses per time the third most costly operation of the

Red Army in the war, losing roughly 87 tanks per diem, 1,997 in toto.

An IS-2 heavy tank (the IS for “Iosif Stalin”), dubbed the “Tank of the Victory," at Proskauerstraße during the advance down Frankfurterallee- a triumphal arch would later be set up in Frankfurterallee which was later to become one of the showpieces of Stalinist

architecture. The IS-2 was the first production model

and mounted a long-barrel 122-mm gun and was in service until the late

1960s. The tank saw combat late in the war in small numbers, notably against Tiger I, Tiger II tanks and Elefant tank destroyers. The Battle of Berlin saw scores of IS-2s employed to destroying entire buildings thanks to their powerful HE rounds in support of the 7th separate Guards (104th, 105th and 106th tank regiments), the 11th Heavy Tank Brigade’s 334th Regiment, the 351st, 396th, 394th regiments from various units and the 362nd and 399th regiments from the 1st Guards Tank Army, the 347th from the 2nd Guards Tank Army, all part of the 1st Belorussian Front, and the 383rd and 384th regiments of the 3rd Guards Tank Army (1st Ukrainian front). They would be tactically arranged into small units of five IS-2s supported by a company of assault infantry, including sappers and flame-throwers. Despite its sloped 4.72 inch thick frontal armour at an angle of 60° and massive 14.8 inch main gun, the shortcuts taken would prove real issues on the long run, starting with the gun itself, slow to reload and with bulky two-piece naval ammunition. Perhaps it shouldn't be too surprising that the Red Army suffered a a considerable

loss of tanks by this stage of the war despite it being the "finishing

blow". Leaving out the frontier battles which are otherwise misleading

given the high numbers of abandoned vehicles, the Battle of Berlin was

in terms of tank losses per time the third most costly operation of the

Red Army in the war, losing roughly 87 tanks per diem, 1,997 in toto.

Soviet troops with PPSh-41 submachine guns entering the Frankfurter Allee station during the climactic Battle of Berlin on April 28, 1945 and my Bavarian International School students during our 2020 school trip. The sign reads: “Public air raid shelters are situated in Frankfurter Allee 113.” At the time this subway station was in the area of urban fortification ring in the defence sector number 2. Berlin, Germany. Nevertheless whilst in the north and east of Berlin the Soviets they encountered fierce resistance from the Flak towers in Humboldthain and Friedrichshain, such sectors as that on Frankfurter Allee in the east saw surprisingly weak resistance. That said, as one American writer, Eddie Gilmore of the Associated Press, who was amongst the first group of correspondents allowed to spend more than 24 hours in the smashed metropolis, wrote on June 9, 1945: "[t]he capital of the Third Reich is a heap of gaunt, burned-out, flame-seared buildings. It is a desert of a hundred thousand dunes made up of brick and powdered masonry. Over this hangs the pungent stench of death . . . It is impossible to exaggerate in describing the destruction . . . Downtown Berlin looks like no thing man could have contrived. Riding down the famous Frankfurter Allee, I did not see a single building where you could have set up a business of even selling apples."

When General Krebs had finally returned to the bunker that afternoon with General Chuikov’s demand for unconditional surrender Hitler’s party secretary had decided that his only chance for survival lay in joining the mass exodus. His group attempted to follow a German tank, but according to Kempka, who was with him, it received a direct hit from a Russian shell and Bormann was almost certainly killed. Artur Axmann, the Hitler Youth leader, who had deserted his battalion of boys at the Pichelsdorf Bridge to save his neck, was also present and later deposed that he had seen Bormann’s body lying under the bridge where the Invalidenstrasse crosses the railroad tracks. There was moonlight on his face and Axmann could see no sign of wounds. His presumption was that Bormann had swallowed his capsule of poison when he saw that his chances of getting through the Russian lines were nil.

Shirer (1019-1020) Rise And Fall Of The Third Reich

An IS-2 heavy tank (the IS for “Iosif Stalin”), dubbed the “Tank of the Victory," at Proskauerstraße during the advance down Frankfurterallee- a triumphal arch would later be set up in Frankfurterallee which was later to become one of the showpieces of Stalinist

architecture. The IS-2 was the first production model

and mounted a long-barrel 122-mm gun and was in service until the late

1960s. The tank saw combat late in the war in small numbers, notably against Tiger I, Tiger II tanks and Elefant tank destroyers. The Battle of Berlin saw scores of IS-2s employed to destroying entire buildings thanks to their powerful HE rounds in support of the 7th separate Guards (104th, 105th and 106th tank regiments), the 11th Heavy Tank Brigade’s 334th Regiment, the 351st, 396th, 394th regiments from various units and the 362nd and 399th regiments from the 1st Guards Tank Army, the 347th from the 2nd Guards Tank Army, all part of the 1st Belorussian Front, and the 383rd and 384th regiments of the 3rd Guards Tank Army (1st Ukrainian front). They would be tactically arranged into small units of five IS-2s supported by a company of assault infantry, including sappers and flame-throwers. Despite its sloped 4.72 inch thick frontal armour at an angle of 60° and massive 14.8 inch main gun, the shortcuts taken would prove real issues on the long run, starting with the gun itself, slow to reload and with bulky two-piece naval ammunition. Perhaps it shouldn't be too surprising that the Red Army suffered a a considerable

loss of tanks by this stage of the war despite it being the "finishing

blow". Leaving out the frontier battles which are otherwise misleading

given the high numbers of abandoned vehicles, the Battle of Berlin was

in terms of tank losses per time the third most costly operation of the

Red Army in the war, losing roughly 87 tanks per diem, 1,997 in toto.

An IS-2 heavy tank (the IS for “Iosif Stalin”), dubbed the “Tank of the Victory," at Proskauerstraße during the advance down Frankfurterallee- a triumphal arch would later be set up in Frankfurterallee which was later to become one of the showpieces of Stalinist

architecture. The IS-2 was the first production model

and mounted a long-barrel 122-mm gun and was in service until the late

1960s. The tank saw combat late in the war in small numbers, notably against Tiger I, Tiger II tanks and Elefant tank destroyers. The Battle of Berlin saw scores of IS-2s employed to destroying entire buildings thanks to their powerful HE rounds in support of the 7th separate Guards (104th, 105th and 106th tank regiments), the 11th Heavy Tank Brigade’s 334th Regiment, the 351st, 396th, 394th regiments from various units and the 362nd and 399th regiments from the 1st Guards Tank Army, the 347th from the 2nd Guards Tank Army, all part of the 1st Belorussian Front, and the 383rd and 384th regiments of the 3rd Guards Tank Army (1st Ukrainian front). They would be tactically arranged into small units of five IS-2s supported by a company of assault infantry, including sappers and flame-throwers. Despite its sloped 4.72 inch thick frontal armour at an angle of 60° and massive 14.8 inch main gun, the shortcuts taken would prove real issues on the long run, starting with the gun itself, slow to reload and with bulky two-piece naval ammunition. Perhaps it shouldn't be too surprising that the Red Army suffered a a considerable

loss of tanks by this stage of the war despite it being the "finishing

blow". Leaving out the frontier battles which are otherwise misleading

given the high numbers of abandoned vehicles, the Battle of Berlin was

in terms of tank losses per time the third most costly operation of the

Red Army in the war, losing roughly 87 tanks per diem, 1,997 in toto. Soviet troops with PPSh-41 submachine guns entering the Frankfurter Allee station during the climactic Battle of Berlin on April 28, 1945 and my Bavarian International School students during our 2020 school trip. The sign reads: “Public air raid shelters are situated in Frankfurter Allee 113.” At the time this subway station was in the area of urban fortification ring in the defence sector number 2. Berlin, Germany. Nevertheless whilst in the north and east of Berlin the Soviets they encountered fierce resistance from the Flak towers in Humboldthain and Friedrichshain, such sectors as that on Frankfurter Allee in the east saw surprisingly weak resistance. That said, as one American writer, Eddie Gilmore of the Associated Press, who was amongst the first group of correspondents allowed to spend more than 24 hours in the smashed metropolis, wrote on June 9, 1945: "[t]he capital of the Third Reich is a heap of gaunt, burned-out, flame-seared buildings. It is a desert of a hundred thousand dunes made up of brick and powdered masonry. Over this hangs the pungent stench of death . . . It is impossible to exaggerate in describing the destruction . . . Downtown Berlin looks like no thing man could have contrived. Riding down the famous Frankfurter Allee, I did not see a single building where you could have set up a business of even selling apples."

The former Reichspostministerium on Leipziger Straße. Under the Nazis it had authority over research and development departments in the areas of television engineering, high-frequency technology, cable (wide-band) transmission, meteorology, and acoustics (microphone technology). In 1942, the armed postal security service was subsumed into the ϟϟ; this was just one more step in the national socialisation of the Deutsche Reichspost. After war the Federal Ministry of Post and Telecommunications in West Germany as well as the East German Ministry of Postal and Telecommunications took over the tasks for postal services. Fritz Kölle's eight-metre wide 'Adler' ('Eagle'), dating 1937, was placed on the façade of the entrance to the Reichspostministerium. The building itself was built between 1871 and 1874; its architect was Carl Schwatlo, who was responsible for numerous buildings for the post office. At the opening, Kaiser Wilhelm I gave an appreciative judgement: “Good! A pure and simply worthy style!" From 1893 to 1897 the building was further expanded according to plans by architects Ernst Hake, Otto Techow and Franz Ahrens and turned into the Reichspostmuseum.  Since 1895 there has been an almost six metre-high sculpture by Ernst Wenck on the roof above the main entrance - giants encompassing the globe as an allegory of the global importance of post and telecommunications. In the Berlin vernacular, the massive building was jokingly known as the Post Coliseum or Stephan Circus after the postmaster general. The building remained closed during the war. As a result of the Allied air raids from 1943 and intensive house-to-house fighting during the Battle of Berlin in April 1945, the building suffered severe damage so that by the end of the war only the surrounding walls were left.

Since 1895 there has been an almost six metre-high sculpture by Ernst Wenck on the roof above the main entrance - giants encompassing the globe as an allegory of the global importance of post and telecommunications. In the Berlin vernacular, the massive building was jokingly known as the Post Coliseum or Stephan Circus after the postmaster general. The building remained closed during the war. As a result of the Allied air raids from 1943 and intensive house-to-house fighting during the Battle of Berlin in April 1945, the building suffered severe damage so that by the end of the war only the surrounding walls were left.

Since 1895 there has been an almost six metre-high sculpture by Ernst Wenck on the roof above the main entrance - giants encompassing the globe as an allegory of the global importance of post and telecommunications. In the Berlin vernacular, the massive building was jokingly known as the Post Coliseum or Stephan Circus after the postmaster general. The building remained closed during the war. As a result of the Allied air raids from 1943 and intensive house-to-house fighting during the Battle of Berlin in April 1945, the building suffered severe damage so that by the end of the war only the surrounding walls were left.

Since 1895 there has been an almost six metre-high sculpture by Ernst Wenck on the roof above the main entrance - giants encompassing the globe as an allegory of the global importance of post and telecommunications. In the Berlin vernacular, the massive building was jokingly known as the Post Coliseum or Stephan Circus after the postmaster general. The building remained closed during the war. As a result of the Allied air raids from 1943 and intensive house-to-house fighting during the Battle of Berlin in April 1945, the building suffered severe damage so that by the end of the war only the surrounding walls were left.After the war the ruins were in the Soviet sector of Berlin. When a small postal museum was to be opened in the Urania building in West Berlin in 1966 - a new Bundespostmuseum was established in Frankfurt am Main in 1958 - work began on the old location on Leipziger Strasse. The result was initially a stamp exhibition in a very limited space in the same year. In April 1960, the Postal Museum was reopened with a permanent exhibition on the development of postal and telecommunications in departments on the history of the postal system, telegraphy and telephony, and radio and television with devices, models and equipment. The exhibition area was expanded in the following years. The building was made a listed building in 1977 and a decade later with a view to the 750th anniversary of Berlin in 1987, the Politburo of the Central Committee of the ruling SED party decided in 1981 to completely rebuild the old Reichspostmuseum and to reopen it as the East German Postal Museum. However, work according to plans by the architect Klaus Niebergall was delayed, and in 1987 only part of the planned exhibition space was available. The remaining construction work was only completed in 1990 after the fall of the Berlin Wall, with the reconstruction of the atrium.

Fehrbellinerplatz just after the war in the Wilmersdorf district. Otto

Firle designed the five-story steel frame construction faced with

limestone at the eastern end of Fehrbelliner Platz for a life insurance

company; it can be seen in the background with its roof destroyed. It had been dedicated in 1936. In order to maximise the use of its frontage facing the square, the narrow sides of the long curved building jutted out over the pavements, extending all the way to the street. The sharp-edged window-framing, between which raised stone slabs create an ornamental net structure, lessen to some extent the monotony of the rows of windows on the expansive facade. The relief sculptures by Waldemar Raemisch still exist facing Hohenzollerndamm, whereas the architectural ornamentation by Arno Breker at the opposite end was removed. The foyer of the building was inspired by art deco. It presently houses Berlin's Senate Department for Urban Development and the Environment.

Entschädigungsbehörde in the Wilmersdorf district was built in 1935-36 by the architect Philipp Schaefer as an office complex for the Rudolf Karstadt department store chain; the Nazi-era reliefs are still present.

Its horseshoe shape was laid out in 1934 and is still surrounded by several administrative buildings of the Nazi era, including the former

seat of the German Labour Front finished in 1943, today the Wilmersdorf

town hall. It remains among the most impressive architectural ensembles

of the Nazi period. In 1913 the area used for allotment community

gardens and an athletic field was connected to the public transportation

network through the construction of an U-bahn station. In the mid-1920s

the square was further upgraded when Preussen Park was established. In

1934, various large companies planned new buildings there, and a public

architectural competition was conducted to create a large, uniform

square. Otto Firle's winning overall development plan for the square was

largely completed. Aligned in an horseshoe shape, the buildings relate

to each other through their design and height, opening up toward the

park in the north.

What's now Rathaus Wilmersdorf at Fehrbelliner Platz 4 was the site of the first British HQ from 1945 to 1953- 'Lancaster House' - which had earlier served as the the former centre of Nazi military administration. It was built by Helmut Remmelmann 1941 and 1943 as the last extension to the existing DAF administration building on Fehrbelliner Platz. It was the last Nazi-era building built on Fehrbellinerplatz on a previously-used sports field and was to have served as the headquarters of the German Labour Front. In fact, after completion, the DAF headquarters did not move into the building as planned, but was used by a Wehrmacht administrative office of the Army High Command until the end of the war. The design of the semicircular shape of the Fehrbelliner Platz, which opens onto Preußenpark, goes back to a design by Otto Firle. As concrete and steel were already allocated elsewhere at the time the building was built, it was traditionally designed as masonry with a plastered façade. It is the only building of its kind on Fehrbelliner Platz. The architect, Helmut Remmelmann, worked in the design department at DAF and the curved front of the building completes the semicircular development on Hohenzollerndamm. The main entrance initially leads into the round, column-flanked courtyard in classical style. The floor plan of the building resembles a keyhole with the round courtyard as the head and a larger farm yard. To achieve a representative impression, the ground floor was designed with horizontal, dark-coloured plaster strips as a base. Parts of the architecture, especially the courtyard, were actually based on the police headquarters built in Copenhagen between 1919 and 1924 by the Danish architect Hack Kampmann. Since it was originally planned for a different purpose, it is one of the few town halls in Berlin, such as those in Wedding or Marzahn, without a town hall tower. Beneath was an underground bunker with 1809 shelters which was probably created during the construction of the building.

From 1945 to 1953 it was the headquarters of the British occupying forces and renamed "Lancaster House."

The military train took the soldiers into Charlottenburg Station, which was their introduction to the city, if they were not lucky enough to fly into Gatow. British soldiers in Berlin wore a flash on their sleeve. It was a black circle rimmed with red – ‘septic arsehole’ they called it. British Control Commission’s headquarters in Berlin was in ‘Lancaster House’ on the Fehrbelliner Platz. George Clare described it as a ‘concave-shaped grey, concrete edifice’ in the style of Albert Speer. Under the British Control Commission there were detachments in each of the boroughs under British control, together with a barracks and an officers’ mess. There were messes all over the British Sector. When George Clare reappeared in officer’s garb on his second tour of duty, he was assigned to one on the Breitenbach Platz which was large and lacked social cachet, and resembled a Lyons Corner House. British Military Government was a large yellow building on the Theodor Heuss Platz. This was the former Adolf Hitler Platz in Charlottenburg, the name of which was changed to Reichskanzlerplatz until it was realised that Hitler too had been chancellor. On the other side of the square was the Marlborough Club, where officers could be gentlemen. For the Other Ranks there was the Winston Club.MacDonogh (254-255) After the Reich - The Brutal History of the Allied Occupation

From June 1921 to July 1, 1932, this building served as the second venue of the Prussian State Theatre in Berlin, which had its main venue in the theatre on Gendarmenmarkt. In May 1933 it was subordinated to Prussian Prime Minister Hermann Göring as the Prussian Theatre of Youth within the Prussian State Theatre, but on December 2, 1933 it was transferred to the city of Berlin with a ceremony and a performance of Schiller's Wilhelm Tell. From 1937 to 1938 Paul Baumgarten's house was extensively rebuilt for the city of Berlin. Baumgarten simplified the façade and the auditorium considerably and changed the face of the theatre with reference to the New Objectivity of the 1920s, but also in line with the prevailing monumental architectural taste of thee Nazis . A “government box” was incorporated with the sculptors Paul Scheurich and Karl Nocke as well as the painter Albert Birkle involved in the renovation. It reopened with Schiller's Kabale und Liebe in 1938, the house became the Schiller Theatre of the Reich capital Berlin. The director was the actor Heinrich George under the pseudonym Heinrich Schmitz. According to Berta Drews, his wife, the theatre was firebombed in September 1943 with the stage roof falling into the auditorium. During an air raid on November 23 of the same year the building was completely destroyed. From 1950 to 1951, it was rebuilt for the city of Berlin according to plans by the architects Heinz Völker and Rolf Grosse.

Wittenbergplatz, then and now. Roger Moorhouse (85) writes how

Wittenbergplatz, then and now. Roger Moorhouse (85) writes how

The primary indicators of the shortages were the rows of empty shelves that were often to be seen in Berlin’s shops. Though this was a problem throughout the city, it was perhaps most remarkable in the expensive department stores in the city centre. As well as a shortage of foodstuffs, Berlin suffered serious shortages of just about everything else, from material goods to consumables and toys. One shopper, for instance, complained after searching for two hours to find something of use in the elite Ka-De-We store on Wittenberg Platz: ‘That big barn is empty’, he said. ‘It is a feat of skill to get rid of fifty pfennigs on all seven floors.’

Berlin at War

Samariterstraße and Rigaerstraße in Friedrichshain in 1945 and today, still recognisable. When the Nazis came to power in 1933, the district was renamed Horst-Wessel-Stadt after the Nazi activist and writer of the Nazi hymn whose slow death, after being shot by communists, in Friedrichshain hospital (shown below) in 1930 was turned into a propaganda event by Joseph Goebbels. During the war Friedrichshain was actually one of the most badly damaged parts of Berlin, as Allied strategic bombers specifically targeted its industries. As late as the nineties, some buildings still displayed bullet holes from the intense house to house fighting during the Battle of Berlin. After the war ended, the boundary between the American and Soviet occupation sectors ran between Friedrichshain and Kreuzberg, with Friedrichshain in the east and Kreuzberg in the west. This became a sealed border between East and West Berlin when the Berlin Wall was built in 1961.

Horst Wessel's grave on January 22, 1933 with Hitler and Goebbels attending and its decrepit state today. Today the grave at St. Nikolai-Friedhof in Berlin-Friedrichshain is slowly disintegrating. The grave here is shown alternately honoured and desecrated on the 70th anniversary of his murder in 2010.

Hitler had planned a major demonstration for the 22nd of January in memory of the late Kampfhed (fight song) composer and SA Sturmführer Horst Wessel, which was to impress upon the Reich capital that his fighting formations, the SA and the ϟϟ, were so strong and fear-inspiring that they could march unhindered through the ‘red’ quarters of Berlin, past the Karl Liebknecht Haus (the Communist headquarters) and across the Bülowplatz.

Hitler speaking at the site Everything went according to schedule. There were no serious disruptions to the rank and file of the 35,000 SA men marching through the streets. Following the parade, a memorial ceremony was held at Horst Wessel’s grave at the Nikolai Cemetery, where Hitler made the following remarks:Every Volk which struggles to the fore from utter misery and defeat to cleanse and liberate itself also produces vocalists who are able to put into words what the masses bear in their innermost hearts. It is thus that the powerful Volksbewegung, the Movement of Germany, has also found the voice able to express what the men in rank feel. With his song, which is sung by millions today, Horst Wessel has erected a monument to himself in ongoing history which shall prevail longer than stone and bronze.Even after centuries have passed, even when not a stone is left standing in this great city of Berlin, one will be mindful of the greatest German liberation movement and its vocalist.Comrades, raise the flags. Horst Wessel, who lies under this stone, is not dead. Every day and every hour his spirit is with us, marching in our ranks.Donarus (219-220) The Complete Hitler

Wessel's song, the melody of which was possibly taken from Etienne Nicolas Méhul's opera Joseph or from the naval song Königsberg-Lied, became the co-national anthem of Germany along with the first stanza of Deutschlandlied. The song was first performed at Wessel's funeral. Banned in Germany, it can be heard by clicking here.

The Städtische Krankenhaus am Friedrichshain, the hospital where Horst Wessel succumbed to his injuries after considerable pain for five weeks on February 23, 1930 and received the status of Nazi martyr. When the Nazis took power, it was renamed in October 1933 the Horst-Wessel-Krankenhaus.

According to the hospital's director who had personally operated on Horst Wessel and melodramatically describes the victim,

Above the corner of the mouth is the entrance hole, the upper jaw is injured, one sees bone splinters and a bullet fragment in the cheek. The bullet passed through the tongue and stopped in the throat in front of the second cervical vertebra, an extremely dangerous location. We fought against the condition of weakness with the usual means, and the patient initially recovered quite tolerably. But I still had the impression of a seriously ill man, who bravely, almost stubbornly, rebelled against his miserable state.On January 17 Horst Wessel could again speak and drink fluids, only the hearing in the left ear was still very weak. At the end of January an improvement was noticeable, but we did not know whether the cervical vertebra had been injured by the bullet fragment in the throat. I attempted to approach the bullet in the throat with a probe.But I had to cease immediately, for the patient collapsed lifeless on the table in front of me. That was the first sign that the illness proceeded pitilessly. On February 11 the condition was very serious. Fever attacks occurred more and more frequently. On February 13 an improvement of the general condition was noticeable. Bullet fragments and bone splinters broke through, and we thought: maybe we’ll make it after all. But the pains at the cervical vertebra, of which he complained, were very ominous to me. For if this bone was injured, the patient was irretrievably lost. Even the slightest penetration into this life essential area had to lead to a gradual decline, to blood poisoning.From February 15 onward the condition worsened more and more and his strength receded. On February 19 the condition worsened. The patient is very restless and the pains became even more tormenting.On February 20 shivering fits set in.On February 21 the patient became more yellow, and others symptoms of a general blood poisoning shown themselves.On February 22 it was a certainty to us that despite all efforts the second cervical vertebra was injured and the patient could no longer be saved. On February 23, at around six-thirty in the morning he quickly passed away.

Wessel leading SA troops in Nuremberg train station

In fact, had Wessel received prompt medical treatment, his life might have been saved. But he refused to use the services of the nearest doctor, because he was a Jew, which meant it was some time before he was taken to the Freidrichshain Hospital.

Himmler, Heydrich, Daluege, and Adolf Hühnlein at a memorial ceremony on German Police Day at Horst Wessel Platz on January 16, 1937

The picture painted by Himmler and leading ϟϟ functionaries of the police, and above all of the Gestapo, was sometimes underlined by such threatening gestures, but sometimes by the assurance that normal citizens had nothing to fear, that they would be treated fairly and justly and, moreover, that the pursuit of opponents was being carried out in accordance with purely objective considerations. Himmler summed up this ambivalent public representation in his speech on the occasion of the 1937 German Police Day in the following formula: "tough and implacable where necessary, understanding and generous where possible."

Longerich (209) Heinrich Himmler: A Life

On the same square was the

Karl Liebknecht house, party headquarters of the German Communist Party (KPD) between

1926 and 1933, shown here in 1932. It was the first new building built on the square in 1912, serving as an office and commercial building, which the KPD acquired in 1926 to set up its headquarters, the Karl-Liebknecht-Haus. It carried the names of a joint founders of the KPD who

were murdered on January 15, 1919 by members of the free corps. The building itself was built in 1910 on behalf of the manufacturer Rudolph Werth as an office building in the then Scheunenviertel. After the Communist Party acquired the house in November 1926, it was named after Karl Liebknecht - the co-founder of the KPD murdered in January 1919 in the course of the November Revolution. Before 1926 the party had its seat on the Hackescher Markt on Rosenthalerstraße. After it was acquired by the KPD it served as the office the Central Committee of the KPD, the KPD district leadership Berlin-Brandenburg-Lausitz-Grenzmark, the editorial offices of the KPD newspaper The Red Flag, a bookstore, the Central Committee of the Communist Youth Association of Germany, a shop for uniforms of the Red Front Fighter Association and a printing house. During that time it was the party leadership offices of Ernst Thalmann, Wilhelm Pieck, Walter Ulbricht and Herbert Wehner. Here too artists such as John Heartfield and Max Gebhard had their studios. On August 9, 1931 KPD members murdered two police officers in the immediate vicinity of the house. These murders on Bülowplatz resulted in the several-day occupation and an unsuccessful search of the party headquarters by the police.

On the same square was the

Karl Liebknecht house, party headquarters of the German Communist Party (KPD) between

1926 and 1933, shown here in 1932. It was the first new building built on the square in 1912, serving as an office and commercial building, which the KPD acquired in 1926 to set up its headquarters, the Karl-Liebknecht-Haus. It carried the names of a joint founders of the KPD who

were murdered on January 15, 1919 by members of the free corps. The building itself was built in 1910 on behalf of the manufacturer Rudolph Werth as an office building in the then Scheunenviertel. After the Communist Party acquired the house in November 1926, it was named after Karl Liebknecht - the co-founder of the KPD murdered in January 1919 in the course of the November Revolution. Before 1926 the party had its seat on the Hackescher Markt on Rosenthalerstraße. After it was acquired by the KPD it served as the office the Central Committee of the KPD, the KPD district leadership Berlin-Brandenburg-Lausitz-Grenzmark, the editorial offices of the KPD newspaper The Red Flag, a bookstore, the Central Committee of the Communist Youth Association of Germany, a shop for uniforms of the Red Front Fighter Association and a printing house. During that time it was the party leadership offices of Ernst Thalmann, Wilhelm Pieck, Walter Ulbricht and Herbert Wehner. Here too artists such as John Heartfield and Max Gebhard had their studios. On August 9, 1931 KPD members murdered two police officers in the immediate vicinity of the house. These murders on Bülowplatz resulted in the several-day occupation and an unsuccessful search of the party headquarters by the police.

Nazis marching past on the way to a memorial for the death of Horst Wessel 1933. The Political Police raided the Karl Liebknecht House again in February 1933 and it was finally closed on February 26.

On the same square was the

Karl Liebknecht house, party headquarters of the German Communist Party (KPD) between

1926 and 1933, shown here in 1932. It was the first new building built on the square in 1912, serving as an office and commercial building, which the KPD acquired in 1926 to set up its headquarters, the Karl-Liebknecht-Haus. It carried the names of a joint founders of the KPD who

were murdered on January 15, 1919 by members of the free corps. The building itself was built in 1910 on behalf of the manufacturer Rudolph Werth as an office building in the then Scheunenviertel. After the Communist Party acquired the house in November 1926, it was named after Karl Liebknecht - the co-founder of the KPD murdered in January 1919 in the course of the November Revolution. Before 1926 the party had its seat on the Hackescher Markt on Rosenthalerstraße. After it was acquired by the KPD it served as the office the Central Committee of the KPD, the KPD district leadership Berlin-Brandenburg-Lausitz-Grenzmark, the editorial offices of the KPD newspaper The Red Flag, a bookstore, the Central Committee of the Communist Youth Association of Germany, a shop for uniforms of the Red Front Fighter Association and a printing house. During that time it was the party leadership offices of Ernst Thalmann, Wilhelm Pieck, Walter Ulbricht and Herbert Wehner. Here too artists such as John Heartfield and Max Gebhard had their studios. On August 9, 1931 KPD members murdered two police officers in the immediate vicinity of the house. These murders on Bülowplatz resulted in the several-day occupation and an unsuccessful search of the party headquarters by the police.

On the same square was the

Karl Liebknecht house, party headquarters of the German Communist Party (KPD) between

1926 and 1933, shown here in 1932. It was the first new building built on the square in 1912, serving as an office and commercial building, which the KPD acquired in 1926 to set up its headquarters, the Karl-Liebknecht-Haus. It carried the names of a joint founders of the KPD who

were murdered on January 15, 1919 by members of the free corps. The building itself was built in 1910 on behalf of the manufacturer Rudolph Werth as an office building in the then Scheunenviertel. After the Communist Party acquired the house in November 1926, it was named after Karl Liebknecht - the co-founder of the KPD murdered in January 1919 in the course of the November Revolution. Before 1926 the party had its seat on the Hackescher Markt on Rosenthalerstraße. After it was acquired by the KPD it served as the office the Central Committee of the KPD, the KPD district leadership Berlin-Brandenburg-Lausitz-Grenzmark, the editorial offices of the KPD newspaper The Red Flag, a bookstore, the Central Committee of the Communist Youth Association of Germany, a shop for uniforms of the Red Front Fighter Association and a printing house. During that time it was the party leadership offices of Ernst Thalmann, Wilhelm Pieck, Walter Ulbricht and Herbert Wehner. Here too artists such as John Heartfield and Max Gebhard had their studios. On August 9, 1931 KPD members murdered two police officers in the immediate vicinity of the house. These murders on Bülowplatz resulted in the several-day occupation and an unsuccessful search of the party headquarters by the police.Nazis marching past on the way to a memorial for the death of Horst Wessel 1933. The Political Police raided the Karl Liebknecht House again in February 1933 and it was finally closed on February 26.

On February 24, Goering’s police raided the Karl Liebknecht Haus, the Communist headquarters in Berlin. It had been abandoned some weeks before by the Communist leaders, a number of whom had already gone underground or quietly slipped off to Russia. But piles of propaganda pamphlets had been left in the cellar and these were enough to enable Goering to announce in an official communique that the seized ”documents” proved that the Communists were about to launch the revolution. The reaction of the public and even of some of the conservatives in the government was one of skepticism. It was obvious that something more sensational must be found to stampede the public before the election took place on March 5.

Shirer (170) Rise And Fall Of The Third Reich

The

SA occupied the building on March 8, 1933 and renamed it Horst-Wessel-Haus. It used it until the summer of 1933 as a "wild" concentration

camp for the terrorisation of Nazi opponents. The communist party was outlawed and its members killed or sent to the concentration camps. The Gestapo found during a

search on November 15, 1933 two hiding places in the building, which had

remained undetected in the previous searches. In addition to two light

machine guns, they contained sixteen additional firearms with ammunition as well as

a large number of files of the party leadership with information on

officials such as CVs, addresses and usage. The findings were probably

based on information from the arrested Alfred Kattner , who had belonged

to Thälmann's inner circle. In 1935 the

new entrance hall was designed as a memorial room for Wessel. As of