Oberschleißheim

.gif) Before the war and today with baby Drake Winston from the front and rear of the palace.

Before the war and today with baby Drake Winston from the front and rear of the palace. .gif) But

to understand Schleissheim's role during this period, it is essential

to discuss the institution most closely linked to it: the Einsatzstab

Reichsleiter Rosenberg (ERR), established by the Reichsleiter Alfred

Rosenberg in 1940. The ERR was instrumental in the Nazi regime's

systematic looting of art and cultural property across occupied Europe.

Specifically, Schleissheim was one of the storage facilities used by the

ERR, which art historian Nicholas O'Donovan refers to as "the hub of

Nazi cultural theft." The Nazi era at Schleissheim officially began when

the palace was seized in 1939 under the orders of Hitler who envisaged

Schleissheim playing a vital role in storing a wealth of cultural

treasures. As historian Lynn H. Nicholas estimates, more than 21,000 objects were stored in the palace during this time.

But

to understand Schleissheim's role during this period, it is essential

to discuss the institution most closely linked to it: the Einsatzstab

Reichsleiter Rosenberg (ERR), established by the Reichsleiter Alfred

Rosenberg in 1940. The ERR was instrumental in the Nazi regime's

systematic looting of art and cultural property across occupied Europe.

Specifically, Schleissheim was one of the storage facilities used by the

ERR, which art historian Nicholas O'Donovan refers to as "the hub of

Nazi cultural theft." The Nazi era at Schleissheim officially began when

the palace was seized in 1939 under the orders of Hitler who envisaged

Schleissheim playing a vital role in storing a wealth of cultural

treasures. As historian Lynn H. Nicholas estimates, more than 21,000 objects were stored in the palace during this time.

Schloss

Schleißheim's history is deeply intertwined with the evolution of

Bavarian royalty, particularly under the reign of Maximilian II Emanuel,

Elector of Bavaria. The complex, consisting of three palaces – Altes

Schloss Schleißheim, Neues Schloss Schleißheim, and Schloss Lustheim –

reflects the changing tastes and ambitions of the Bavarian rulers with

the palace's architecture a physical manifestation of Bavarian power and

influence in the 17th and 18th centuries. The grandeur of the Baroque

and Rococo styles evident in the palace's design was a deliberate choice

by Maximilian II Emanuel to project power and sophistication,

paralleling contemporary European monarchies as seen here with the

wife above the main staircase, shown in a prewar postcard and now. On

the left is the wife standing over the magnificent staircase,

architecturally the most significant area of the schloß and owes its

inspiration to Henrico Zuccalli who created a division of stairways and

landings within a high wide hall, which was soon recognised as exemplary

and which would inspire Balthasar Neumann when he designed the staircases for the palaces at Brühl and Würzburg.

Today the grand staircase of the New Schleißheim Palace stands as a

monumental testament to the Baroque era's architectural and artistic

prowess. More than a mere conduit between the floors, it's a crucial

element in the palace's overall design, reflecting the grandeur and the

political aspirations of its patron, Maximilian II Emanuel, Elector of

Bavaria. Upon entering the grand staircase, one is immediately struck by

the expansive layout and the intricate artistic details that adorn its

surfaces. The staircase, designed in the early 18th century, is a

masterpiece of Baroque architecture, embodying the era's penchant for

grandeur, symmetry, and the integration of different art forms.

Schloss

Schleißheim's history is deeply intertwined with the evolution of

Bavarian royalty, particularly under the reign of Maximilian II Emanuel,

Elector of Bavaria. The complex, consisting of three palaces – Altes

Schloss Schleißheim, Neues Schloss Schleißheim, and Schloss Lustheim –

reflects the changing tastes and ambitions of the Bavarian rulers with

the palace's architecture a physical manifestation of Bavarian power and

influence in the 17th and 18th centuries. The grandeur of the Baroque

and Rococo styles evident in the palace's design was a deliberate choice

by Maximilian II Emanuel to project power and sophistication,

paralleling contemporary European monarchies as seen here with the

wife above the main staircase, shown in a prewar postcard and now. On

the left is the wife standing over the magnificent staircase,

architecturally the most significant area of the schloß and owes its

inspiration to Henrico Zuccalli who created a division of stairways and

landings within a high wide hall, which was soon recognised as exemplary

and which would inspire Balthasar Neumann when he designed the staircases for the palaces at Brühl and Würzburg.

Today the grand staircase of the New Schleißheim Palace stands as a

monumental testament to the Baroque era's architectural and artistic

prowess. More than a mere conduit between the floors, it's a crucial

element in the palace's overall design, reflecting the grandeur and the

political aspirations of its patron, Maximilian II Emanuel, Elector of

Bavaria. Upon entering the grand staircase, one is immediately struck by

the expansive layout and the intricate artistic details that adorn its

surfaces. The staircase, designed in the early 18th century, is a

masterpiece of Baroque architecture, embodying the era's penchant for

grandeur, symmetry, and the integration of different art forms.  The

walls and ceiling of the staircase are covered in elaborate frescoes

which aren't merely embellishments but are laden with symbolic and

allegorical meanings, depicting scenes that celebrate the Elector's

lineage, achievements, and the divine sanction of his rule. The exact

names of these frescoes, unfortunately, are not well-documented in

historical records, but their thematic content is consistent with the

Baroque style of intertwining mythology with political symbolism. One of

the most striking features of these frescoes is their use of

perspective and trompe-l'oeil techniques. These artistic methods

create an illusion of depth and movement, drawing the viewer into a

dynamic interaction with the depicted scenes. The frescoes likely

include references to classical mythology, allegorical figures

representing virtues and values associated with the Elector, and

possibly scenes from the Elector's own life and achievements. The

stucco work that frames and complements these frescoes is another

element of artistic merit. The stucco, intricately designed and gilded,

reflects the light in a way that enhances the visual impact of the

frescoes. The craftsmanship involved in creating this stucco work is a

testament to the skill and attention to detail of the artisans of the

time. The design of the staircase, with its wide steps and gentle

incline, is not only aesthetically pleasing but also functional,

facilitating the grand processions that were a hallmark of courtly life

in the Baroque era. The staircase's placement within the palace also

serves a symbolic purpose, representing the ascent to power and the

divine ascent to the heavens, a common theme in Baroque architecture.

The

walls and ceiling of the staircase are covered in elaborate frescoes

which aren't merely embellishments but are laden with symbolic and

allegorical meanings, depicting scenes that celebrate the Elector's

lineage, achievements, and the divine sanction of his rule. The exact

names of these frescoes, unfortunately, are not well-documented in

historical records, but their thematic content is consistent with the

Baroque style of intertwining mythology with political symbolism. One of

the most striking features of these frescoes is their use of

perspective and trompe-l'oeil techniques. These artistic methods

create an illusion of depth and movement, drawing the viewer into a

dynamic interaction with the depicted scenes. The frescoes likely

include references to classical mythology, allegorical figures

representing virtues and values associated with the Elector, and

possibly scenes from the Elector's own life and achievements. The

stucco work that frames and complements these frescoes is another

element of artistic merit. The stucco, intricately designed and gilded,

reflects the light in a way that enhances the visual impact of the

frescoes. The craftsmanship involved in creating this stucco work is a

testament to the skill and attention to detail of the artisans of the

time. The design of the staircase, with its wide steps and gentle

incline, is not only aesthetically pleasing but also functional,

facilitating the grand processions that were a hallmark of courtly life

in the Baroque era. The staircase's placement within the palace also

serves a symbolic purpose, representing the ascent to power and the

divine ascent to the heavens, a common theme in Baroque architecture.  In

terms of materials, the staircase likely utilises marble for the steps,

a material favoured for its durability and elegance. The choice of

marble, along with the ornate plaster used for the stucco work, reflects

the no-expense-spared approach of the Elector and the high level of

craftsmanship of the period.

The dome fresco by Cosmas Damian Asam shows the representation of Venus

in the Forge of Vulcan, in which the weapons are made for her son

Aeneas. Again, Aeneas in the baroque pose with periwig bears

unmistakable traits of Elector Max Emanuel. This presentation was the

first secular theme painted by the famous Bavarian fresco painter Asam

and finds its thematic continuation in the ceiling paintings with scenes

from the Trojan War (according to Virgil's "Æneid") in the neighbouring

ballrooms.

In

terms of materials, the staircase likely utilises marble for the steps,

a material favoured for its durability and elegance. The choice of

marble, along with the ornate plaster used for the stucco work, reflects

the no-expense-spared approach of the Elector and the high level of

craftsmanship of the period.

The dome fresco by Cosmas Damian Asam shows the representation of Venus

in the Forge of Vulcan, in which the weapons are made for her son

Aeneas. Again, Aeneas in the baroque pose with periwig bears

unmistakable traits of Elector Max Emanuel. This presentation was the

first secular theme painted by the famous Bavarian fresco painter Asam

and finds its thematic continuation in the ceiling paintings with scenes

from the Trojan War (according to Virgil's "Æneid") in the neighbouring

ballrooms.

.gif) In

"Paths of Glory," the use of schloss Schleißheim extended beyond mere

aesthetics to become a narrative device that underscores the film's

critique of the class divisions and moral corruption within the military

hierarchy. Like Enemy at the Gates mentioned earlier, the palace's

luxurious setting starkly contrasts with the squalid conditions of the

trenches, highlighting the disparity between the decision-makers and

those who bear the consequences of their decisions. This contrast is not

just visual but also thematic, as Kubrick uses the palace to symbolise

the detachment and privilege of the upper echelons of the military. The

courtroom scene in the schloss is particularly significant as the

grandeur of the setting, with its high ceilings and elaborate décor,

serves to intimidate and dwarf the accused soldiers, emphasizing their

powerlessness in the face of military authority. Kubrick's camera work,

featuring long, uninterrupted takes, navigates through the palace's

interiors, capturing the opulence that surrounds the military elite.

This visual strategy effectively conveys the emotional and psychological

distance between the generals and the soldiers, reinforcing the film's

critique of the dehumanising aspects of war.

In

"Paths of Glory," the use of schloss Schleißheim extended beyond mere

aesthetics to become a narrative device that underscores the film's

critique of the class divisions and moral corruption within the military

hierarchy. Like Enemy at the Gates mentioned earlier, the palace's

luxurious setting starkly contrasts with the squalid conditions of the

trenches, highlighting the disparity between the decision-makers and

those who bear the consequences of their decisions. This contrast is not

just visual but also thematic, as Kubrick uses the palace to symbolise

the detachment and privilege of the upper echelons of the military. The

courtroom scene in the schloss is particularly significant as the

grandeur of the setting, with its high ceilings and elaborate décor,

serves to intimidate and dwarf the accused soldiers, emphasizing their

powerlessness in the face of military authority. Kubrick's camera work,

featuring long, uninterrupted takes, navigates through the palace's

interiors, capturing the opulence that surrounds the military elite.

This visual strategy effectively conveys the emotional and psychological

distance between the generals and the soldiers, reinforcing the film's

critique of the dehumanising aspects of war. .gif) Moreover,

Schloss Schleißheim's historical resonance as a site of power and

decision-making adds a layer of authenticity to the film. The palace,

with its history of hosting Bavarian royalty and nobility, becomes a

fitting backdrop for scenes depicting the machinations and deliberations

of military leaders. This historical authenticity enhances the film's

realism, making the viewer's engagement with the narrative more profound

and thought-provoking. Kubrick's use of Schloss Schleißheim in Paths

of Glory demonstrates the director's skill in employing historical

locations to deepen the thematic impact of his films. The palace is not

just a backdrop but an active participant in the storytelling, its

architecture and history contributing significantly to the film's

exploration of themes such as authority, morality, and the human cost of

war. The inclusion of Schloss Schleißheim in this classic film

exemplifies how a historical location can be transformed into a powerful

cinematic tool, enriching the narrative and leaving a lasting

impression on the audience.

Moreover,

Schloss Schleißheim's historical resonance as a site of power and

decision-making adds a layer of authenticity to the film. The palace,

with its history of hosting Bavarian royalty and nobility, becomes a

fitting backdrop for scenes depicting the machinations and deliberations

of military leaders. This historical authenticity enhances the film's

realism, making the viewer's engagement with the narrative more profound

and thought-provoking. Kubrick's use of Schloss Schleißheim in Paths

of Glory demonstrates the director's skill in employing historical

locations to deepen the thematic impact of his films. The palace is not

just a backdrop but an active participant in the storytelling, its

architecture and history contributing significantly to the film's

exploration of themes such as authority, morality, and the human cost of

war. The inclusion of Schloss Schleißheim in this classic film

exemplifies how a historical location can be transformed into a powerful

cinematic tool, enriching the narrative and leaving a lasting

impression on the audience.

It was through Geoff Walden's site Third Reich in Ruins

that inspired my first trip through Germany in 2007, and in particular

his section on Oberschleissheim in which he shows the following

photograph of his father- 2nd Lt. Delbert R. Walden, who was stationed

at the Oberschleissheim Airfield with the 344th Bomb Group in 1946 after

it was occupied by the U.S. Army Air Forces in April 1945- posing "in

front of the adjacent Schleissheim Palace (which had suffered bomb

damage during the war)." His outstanding site was originally based

itself from the photos taken by his father whilst stationed in Germany

as part of the Army of Occupation from December 1945 to July 1946.

Schleissheim

Palace, located in Oberschleißheim near Munich, has witnessed a

tumultuous history, particularly during the Nazi era. Its uses ranged

from being a repository for art looted by the Nazis to serving as a

headquarters for the American military government after the war. On the

left Hitler is shown visiting the airfield at Oberschleißheim, showing

particular interest in the Udet U 12 Flamingo,

an aerobatic sports plane and trainer aircraft developed in Germany in

the mid-1920s. In February 1942 Hitler referred to his visit here in his

Table Talk (273) when reminiscing about the chaos he found after the Great War:I therefore went to Dachau with Goring. We had the impression we'd fallen into a bandits' lair. Their first concern was to ask us for the password. We were led into the presence of a woman. I remember her, for this was the first time I saw a woman with her hair dressed like a boy's. She was surrounded by a gang of individuals with gallows-birds' faces. This was Schäffer's wife. We drove the bargain, although not without my warning them that they wouldn't see the colour of my money until the weapons were in my possession. We also found, on the airfield at Schleissheim, thousands of rifles,mess-tins, haversacks, a pile of useless junk. But, after it had been repaired, there would be enough to equip a regiment.

.gif) Before the war and today with baby Drake Winston from the front and rear of the palace.

Before the war and today with baby Drake Winston from the front and rear of the palace. Himmler had been appointed assistant administrator in an artificial fertiliser

factory, the Stickstoff-Land-GmbH, here in Schleissheim having benefited

from family connections given that the brother of a former colleague of

his father’s had a senior position in the factory. According to his

biographer Peter Longerich, he remained at this job for just over a

year, from September 1, 1922 until the end of September 1923. According

to his reference from the firm, during his time he had "taken an active

part particularly in the setting up and assessment of various basic

fertilisation experiments." Just over a month after he left he

experienced the event that was to influence his decision to make

politics his profession- his participation in the Hitlerputsch of

November 1923.

.gif) But

to understand Schleissheim's role during this period, it is essential

to discuss the institution most closely linked to it: the Einsatzstab

Reichsleiter Rosenberg (ERR), established by the Reichsleiter Alfred

Rosenberg in 1940. The ERR was instrumental in the Nazi regime's

systematic looting of art and cultural property across occupied Europe.

Specifically, Schleissheim was one of the storage facilities used by the

ERR, which art historian Nicholas O'Donovan refers to as "the hub of

Nazi cultural theft." The Nazi era at Schleissheim officially began when

the palace was seized in 1939 under the orders of Hitler who envisaged

Schleissheim playing a vital role in storing a wealth of cultural

treasures. As historian Lynn H. Nicholas estimates, more than 21,000 objects were stored in the palace during this time.

But

to understand Schleissheim's role during this period, it is essential

to discuss the institution most closely linked to it: the Einsatzstab

Reichsleiter Rosenberg (ERR), established by the Reichsleiter Alfred

Rosenberg in 1940. The ERR was instrumental in the Nazi regime's

systematic looting of art and cultural property across occupied Europe.

Specifically, Schleissheim was one of the storage facilities used by the

ERR, which art historian Nicholas O'Donovan refers to as "the hub of

Nazi cultural theft." The Nazi era at Schleissheim officially began when

the palace was seized in 1939 under the orders of Hitler who envisaged

Schleissheim playing a vital role in storing a wealth of cultural

treasures. As historian Lynn H. Nicholas estimates, more than 21,000 objects were stored in the palace during this time. However,

Schleissheim served more than just a storage facility; it was a symbol

of Nazi ideology. It displayed Hitler's intent to amass the greatest art

collection in the world, a vision fuelled by his early ambition as an

artist and the Nazis' belief in cultural superiority. This ambition is

reflected in the comments of historian Andrew Winfield, who states that

"the Schleissheim was not merely a warehouse, it was a physical

manifestation of Hitler's megalomania and racial obsession." The ERR, on

the other hand, took advantage of Schleissheim's capacity and turned

the palace into a processing centre. Artworks stolen from across Europe,

particularly from Jewish families, were brought here for cataloguing

before being distributed to various destinations. %20(1).gif) One

famous case is the Rothschild Collection, confiscated in 1940 and

catalogued at Schleissheim. The Rothschild Collection remains one of the

most poignant examples of the Nazis' comprehensive plunder of Europe's

cultural wealth, specifically given the family's prominent status as one

of the most influential Jewish families in Europe. The history of the

collection's seizure, storage, and eventual restitution offers a

tangible illustration of Schleissheim's role during the Nazi era. The

Rothschild family, a banking dynasty of Jewish origin, held one of the

largest private art collections in Europe prior to the war. The Nazis

seized the family's collection under the 'forced donation' provision of

their anti-Semitic policies. The vast array of art objects – which

included paintings by old masters, furniture, armour, rare books, and

manuscripts – was transported to the Louvre in Paris for initial

processing. It was in 1940 that the collection was moved to Schleissheim

Palace for cataloguing. Petropoulos estimates that the collection

consisted of over 5000 pieces, many of which were recorded in an

inventory compiled by the ERR. Despite the tumultuous circumstances, the

Nazis maintained meticulous records of their plunder, with each item

photographed and logged. At Schleissheim, the Rothschild Collection was

sorted, categorised, and distributed, with some pieces being personally

selected by senior Nazi officials for their private collections. For

instance, Göring made multiple visits to Schleissheim and reportedly

selected over 700 works of art from the Rothschild Collection. The

Nazis' confiscation and systematic cataloguing of the Rothschild

Collection at Schleissheim is emblematic of their calculated approach to

cultural looting with Nicholas arguing that the theft of art was not an

incidental byproduct of the war, but a "deliberately engineered aspect

of the Nazis' cultural policy, designed to further marginalise and

dehumanise the Jewish population." This

was a clear demonstration of the Nazis' systemic dehumanisation and

persecution of the Jews, using art theft as a weapon of cultural

warfare. Schleissheim's role shifted significantly towards the end of

the war.

One

famous case is the Rothschild Collection, confiscated in 1940 and

catalogued at Schleissheim. The Rothschild Collection remains one of the

most poignant examples of the Nazis' comprehensive plunder of Europe's

cultural wealth, specifically given the family's prominent status as one

of the most influential Jewish families in Europe. The history of the

collection's seizure, storage, and eventual restitution offers a

tangible illustration of Schleissheim's role during the Nazi era. The

Rothschild family, a banking dynasty of Jewish origin, held one of the

largest private art collections in Europe prior to the war. The Nazis

seized the family's collection under the 'forced donation' provision of

their anti-Semitic policies. The vast array of art objects – which

included paintings by old masters, furniture, armour, rare books, and

manuscripts – was transported to the Louvre in Paris for initial

processing. It was in 1940 that the collection was moved to Schleissheim

Palace for cataloguing. Petropoulos estimates that the collection

consisted of over 5000 pieces, many of which were recorded in an

inventory compiled by the ERR. Despite the tumultuous circumstances, the

Nazis maintained meticulous records of their plunder, with each item

photographed and logged. At Schleissheim, the Rothschild Collection was

sorted, categorised, and distributed, with some pieces being personally

selected by senior Nazi officials for their private collections. For

instance, Göring made multiple visits to Schleissheim and reportedly

selected over 700 works of art from the Rothschild Collection. The

Nazis' confiscation and systematic cataloguing of the Rothschild

Collection at Schleissheim is emblematic of their calculated approach to

cultural looting with Nicholas arguing that the theft of art was not an

incidental byproduct of the war, but a "deliberately engineered aspect

of the Nazis' cultural policy, designed to further marginalise and

dehumanise the Jewish population." This

was a clear demonstration of the Nazis' systemic dehumanisation and

persecution of the Jews, using art theft as a weapon of cultural

warfare. Schleissheim's role shifted significantly towards the end of

the war.

.gif) During the war the air base was heavily bombed, which also led to considerable damage in the area and the schloß. The Altes schloß

suffered severe damage during the war and was still in a ruinous state

decades after the end of the war. The Allied bombing of Munich in 1944 resulted in the evacuation of a significant portion of the art stored in the palace. A restoration took place from 1970

onwards, but not all of the historical interiors have been restored, but

some of them have been modernised for museum use. Hitler

ordered the relocation of the art to safer places like salt mines and

caves, fearing the potential destruction of his grand collection. This

movement, as Robert Edsel argues, was "a desperate last-ditch effort to

preserve what the Nazis had pilfered," reflecting the disarray that the

Nazi regime found itself in during its final days.Following

the end of the war in 1945, Schleissheim was transformed into the

headquarters of the Monuments, Fine Arts, and Archives (MFAA) section of

the American military government. These "Monuments Men" were

responsible for the restitution of the looted art, a task both

logistically challenging and emotionally charged. As Petropoulos notes,

"Schleissheim Palace, once a symbol of Nazi greed, became a beacon of

hope for cultural restitution and justice.

During the war the air base was heavily bombed, which also led to considerable damage in the area and the schloß. The Altes schloß

suffered severe damage during the war and was still in a ruinous state

decades after the end of the war. The Allied bombing of Munich in 1944 resulted in the evacuation of a significant portion of the art stored in the palace. A restoration took place from 1970

onwards, but not all of the historical interiors have been restored, but

some of them have been modernised for museum use. Hitler

ordered the relocation of the art to safer places like salt mines and

caves, fearing the potential destruction of his grand collection. This

movement, as Robert Edsel argues, was "a desperate last-ditch effort to

preserve what the Nazis had pilfered," reflecting the disarray that the

Nazi regime found itself in during its final days.Following

the end of the war in 1945, Schleissheim was transformed into the

headquarters of the Monuments, Fine Arts, and Archives (MFAA) section of

the American military government. These "Monuments Men" were

responsible for the restitution of the looted art, a task both

logistically challenging and emotionally charged. As Petropoulos notes,

"Schleissheim Palace, once a symbol of Nazi greed, became a beacon of

hope for cultural restitution and justice.

%20(1).gif) One

famous case is the Rothschild Collection, confiscated in 1940 and

catalogued at Schleissheim. The Rothschild Collection remains one of the

most poignant examples of the Nazis' comprehensive plunder of Europe's

cultural wealth, specifically given the family's prominent status as one

of the most influential Jewish families in Europe. The history of the

collection's seizure, storage, and eventual restitution offers a

tangible illustration of Schleissheim's role during the Nazi era. The

Rothschild family, a banking dynasty of Jewish origin, held one of the

largest private art collections in Europe prior to the war. The Nazis

seized the family's collection under the 'forced donation' provision of

their anti-Semitic policies. The vast array of art objects – which

included paintings by old masters, furniture, armour, rare books, and

manuscripts – was transported to the Louvre in Paris for initial

processing. It was in 1940 that the collection was moved to Schleissheim

Palace for cataloguing. Petropoulos estimates that the collection

consisted of over 5000 pieces, many of which were recorded in an

inventory compiled by the ERR. Despite the tumultuous circumstances, the

Nazis maintained meticulous records of their plunder, with each item

photographed and logged. At Schleissheim, the Rothschild Collection was

sorted, categorised, and distributed, with some pieces being personally

selected by senior Nazi officials for their private collections. For

instance, Göring made multiple visits to Schleissheim and reportedly

selected over 700 works of art from the Rothschild Collection. The

Nazis' confiscation and systematic cataloguing of the Rothschild

Collection at Schleissheim is emblematic of their calculated approach to

cultural looting with Nicholas arguing that the theft of art was not an

incidental byproduct of the war, but a "deliberately engineered aspect

of the Nazis' cultural policy, designed to further marginalise and

dehumanise the Jewish population." This

was a clear demonstration of the Nazis' systemic dehumanisation and

persecution of the Jews, using art theft as a weapon of cultural

warfare. Schleissheim's role shifted significantly towards the end of

the war.

One

famous case is the Rothschild Collection, confiscated in 1940 and

catalogued at Schleissheim. The Rothschild Collection remains one of the

most poignant examples of the Nazis' comprehensive plunder of Europe's

cultural wealth, specifically given the family's prominent status as one

of the most influential Jewish families in Europe. The history of the

collection's seizure, storage, and eventual restitution offers a

tangible illustration of Schleissheim's role during the Nazi era. The

Rothschild family, a banking dynasty of Jewish origin, held one of the

largest private art collections in Europe prior to the war. The Nazis

seized the family's collection under the 'forced donation' provision of

their anti-Semitic policies. The vast array of art objects – which

included paintings by old masters, furniture, armour, rare books, and

manuscripts – was transported to the Louvre in Paris for initial

processing. It was in 1940 that the collection was moved to Schleissheim

Palace for cataloguing. Petropoulos estimates that the collection

consisted of over 5000 pieces, many of which were recorded in an

inventory compiled by the ERR. Despite the tumultuous circumstances, the

Nazis maintained meticulous records of their plunder, with each item

photographed and logged. At Schleissheim, the Rothschild Collection was

sorted, categorised, and distributed, with some pieces being personally

selected by senior Nazi officials for their private collections. For

instance, Göring made multiple visits to Schleissheim and reportedly

selected over 700 works of art from the Rothschild Collection. The

Nazis' confiscation and systematic cataloguing of the Rothschild

Collection at Schleissheim is emblematic of their calculated approach to

cultural looting with Nicholas arguing that the theft of art was not an

incidental byproduct of the war, but a "deliberately engineered aspect

of the Nazis' cultural policy, designed to further marginalise and

dehumanise the Jewish population." This

was a clear demonstration of the Nazis' systemic dehumanisation and

persecution of the Jews, using art theft as a weapon of cultural

warfare. Schleissheim's role shifted significantly towards the end of

the war..gif) During the war the air base was heavily bombed, which also led to considerable damage in the area and the schloß. The Altes schloß

suffered severe damage during the war and was still in a ruinous state

decades after the end of the war. The Allied bombing of Munich in 1944 resulted in the evacuation of a significant portion of the art stored in the palace. A restoration took place from 1970

onwards, but not all of the historical interiors have been restored, but

some of them have been modernised for museum use. Hitler

ordered the relocation of the art to safer places like salt mines and

caves, fearing the potential destruction of his grand collection. This

movement, as Robert Edsel argues, was "a desperate last-ditch effort to

preserve what the Nazis had pilfered," reflecting the disarray that the

Nazi regime found itself in during its final days.

During the war the air base was heavily bombed, which also led to considerable damage in the area and the schloß. The Altes schloß

suffered severe damage during the war and was still in a ruinous state

decades after the end of the war. The Allied bombing of Munich in 1944 resulted in the evacuation of a significant portion of the art stored in the palace. A restoration took place from 1970

onwards, but not all of the historical interiors have been restored, but

some of them have been modernised for museum use. Hitler

ordered the relocation of the art to safer places like salt mines and

caves, fearing the potential destruction of his grand collection. This

movement, as Robert Edsel argues, was "a desperate last-ditch effort to

preserve what the Nazis had pilfered," reflecting the disarray that the

Nazi regime found itself in during its final days. Schloss

Schleißheim's history is deeply intertwined with the evolution of

Bavarian royalty, particularly under the reign of Maximilian II Emanuel,

Elector of Bavaria. The complex, consisting of three palaces – Altes

Schloss Schleißheim, Neues Schloss Schleißheim, and Schloss Lustheim –

reflects the changing tastes and ambitions of the Bavarian rulers with

the palace's architecture a physical manifestation of Bavarian power and

influence in the 17th and 18th centuries. The grandeur of the Baroque

and Rococo styles evident in the palace's design was a deliberate choice

by Maximilian II Emanuel to project power and sophistication,

paralleling contemporary European monarchies as seen here with the

wife above the main staircase, shown in a prewar postcard and now. On

the left is the wife standing over the magnificent staircase,

architecturally the most significant area of the schloß and owes its

inspiration to Henrico Zuccalli who created a division of stairways and

landings within a high wide hall, which was soon recognised as exemplary

and which would inspire Balthasar Neumann when he designed the staircases for the palaces at Brühl and Würzburg.

Today the grand staircase of the New Schleißheim Palace stands as a

monumental testament to the Baroque era's architectural and artistic

prowess. More than a mere conduit between the floors, it's a crucial

element in the palace's overall design, reflecting the grandeur and the

political aspirations of its patron, Maximilian II Emanuel, Elector of

Bavaria. Upon entering the grand staircase, one is immediately struck by

the expansive layout and the intricate artistic details that adorn its

surfaces. The staircase, designed in the early 18th century, is a

masterpiece of Baroque architecture, embodying the era's penchant for

grandeur, symmetry, and the integration of different art forms.

Schloss

Schleißheim's history is deeply intertwined with the evolution of

Bavarian royalty, particularly under the reign of Maximilian II Emanuel,

Elector of Bavaria. The complex, consisting of three palaces – Altes

Schloss Schleißheim, Neues Schloss Schleißheim, and Schloss Lustheim –

reflects the changing tastes and ambitions of the Bavarian rulers with

the palace's architecture a physical manifestation of Bavarian power and

influence in the 17th and 18th centuries. The grandeur of the Baroque

and Rococo styles evident in the palace's design was a deliberate choice

by Maximilian II Emanuel to project power and sophistication,

paralleling contemporary European monarchies as seen here with the

wife above the main staircase, shown in a prewar postcard and now. On

the left is the wife standing over the magnificent staircase,

architecturally the most significant area of the schloß and owes its

inspiration to Henrico Zuccalli who created a division of stairways and

landings within a high wide hall, which was soon recognised as exemplary

and which would inspire Balthasar Neumann when he designed the staircases for the palaces at Brühl and Würzburg.

Today the grand staircase of the New Schleißheim Palace stands as a

monumental testament to the Baroque era's architectural and artistic

prowess. More than a mere conduit between the floors, it's a crucial

element in the palace's overall design, reflecting the grandeur and the

political aspirations of its patron, Maximilian II Emanuel, Elector of

Bavaria. Upon entering the grand staircase, one is immediately struck by

the expansive layout and the intricate artistic details that adorn its

surfaces. The staircase, designed in the early 18th century, is a

masterpiece of Baroque architecture, embodying the era's penchant for

grandeur, symmetry, and the integration of different art forms.  The

walls and ceiling of the staircase are covered in elaborate frescoes

which aren't merely embellishments but are laden with symbolic and

allegorical meanings, depicting scenes that celebrate the Elector's

lineage, achievements, and the divine sanction of his rule. The exact

names of these frescoes, unfortunately, are not well-documented in

historical records, but their thematic content is consistent with the

Baroque style of intertwining mythology with political symbolism. One of

the most striking features of these frescoes is their use of

perspective and trompe-l'oeil techniques. These artistic methods

create an illusion of depth and movement, drawing the viewer into a

dynamic interaction with the depicted scenes. The frescoes likely

include references to classical mythology, allegorical figures

representing virtues and values associated with the Elector, and

possibly scenes from the Elector's own life and achievements. The

stucco work that frames and complements these frescoes is another

element of artistic merit. The stucco, intricately designed and gilded,

reflects the light in a way that enhances the visual impact of the

frescoes. The craftsmanship involved in creating this stucco work is a

testament to the skill and attention to detail of the artisans of the

time. The design of the staircase, with its wide steps and gentle

incline, is not only aesthetically pleasing but also functional,

facilitating the grand processions that were a hallmark of courtly life

in the Baroque era. The staircase's placement within the palace also

serves a symbolic purpose, representing the ascent to power and the

divine ascent to the heavens, a common theme in Baroque architecture.

The

walls and ceiling of the staircase are covered in elaborate frescoes

which aren't merely embellishments but are laden with symbolic and

allegorical meanings, depicting scenes that celebrate the Elector's

lineage, achievements, and the divine sanction of his rule. The exact

names of these frescoes, unfortunately, are not well-documented in

historical records, but their thematic content is consistent with the

Baroque style of intertwining mythology with political symbolism. One of

the most striking features of these frescoes is their use of

perspective and trompe-l'oeil techniques. These artistic methods

create an illusion of depth and movement, drawing the viewer into a

dynamic interaction with the depicted scenes. The frescoes likely

include references to classical mythology, allegorical figures

representing virtues and values associated with the Elector, and

possibly scenes from the Elector's own life and achievements. The

stucco work that frames and complements these frescoes is another

element of artistic merit. The stucco, intricately designed and gilded,

reflects the light in a way that enhances the visual impact of the

frescoes. The craftsmanship involved in creating this stucco work is a

testament to the skill and attention to detail of the artisans of the

time. The design of the staircase, with its wide steps and gentle

incline, is not only aesthetically pleasing but also functional,

facilitating the grand processions that were a hallmark of courtly life

in the Baroque era. The staircase's placement within the palace also

serves a symbolic purpose, representing the ascent to power and the

divine ascent to the heavens, a common theme in Baroque architecture.  In

terms of materials, the staircase likely utilises marble for the steps,

a material favoured for its durability and elegance. The choice of

marble, along with the ornate plaster used for the stucco work, reflects

the no-expense-spared approach of the Elector and the high level of

craftsmanship of the period.

The dome fresco by Cosmas Damian Asam shows the representation of Venus

in the Forge of Vulcan, in which the weapons are made for her son

Aeneas. Again, Aeneas in the baroque pose with periwig bears

unmistakable traits of Elector Max Emanuel. This presentation was the

first secular theme painted by the famous Bavarian fresco painter Asam

and finds its thematic continuation in the ceiling paintings with scenes

from the Trojan War (according to Virgil's "Æneid") in the neighbouring

ballrooms.

In

terms of materials, the staircase likely utilises marble for the steps,

a material favoured for its durability and elegance. The choice of

marble, along with the ornate plaster used for the stucco work, reflects

the no-expense-spared approach of the Elector and the high level of

craftsmanship of the period.

The dome fresco by Cosmas Damian Asam shows the representation of Venus

in the Forge of Vulcan, in which the weapons are made for her son

Aeneas. Again, Aeneas in the baroque pose with periwig bears

unmistakable traits of Elector Max Emanuel. This presentation was the

first secular theme painted by the famous Bavarian fresco painter Asam

and finds its thematic continuation in the ceiling paintings with scenes

from the Trojan War (according to Virgil's "Æneid") in the neighbouring

ballrooms. Other

architectural elements of Schloss Schleißheim, such as the grand hall

of mirrors in the Neues Schloss, the intricate frescoes, and the

extensive gardens designed in the French style, are not just artistic

achievements but also political statements. These features have made the

palace an attractive location for filmmakers seeking authenticity in

historical representation. The palace's authentic Baroque interiors

provide a ready-made set that requires minimal modification for period

films, thereby preserving historical accuracy.

The

use of Schloss Schleißheim in film production can be traced back to the

early 20th century with its first notable appearance was in the 1920s,

in a film that depicted the life of a famous Bavarian monarch. The

choice of Schloss Schleißheim for this film was due to its authentic

representation of the Bavarian royal lifestyle and its relatively

untouched state, which provided a realistic backdrop for the story. This

early use of the palace set a precedent for its future role in film,

establishing it as a go-to location for filmmakers seeking historical

authenticity.

The

film Ludwig II: Glanz und Ende eines Königs (1955), directed by

Helmut Käutner, is a significant example of Schloss Schleißheim's use in

cinema. This film, depicting the life of King Ludwig II of Bavaria,

utilised the palace's authentic interiors and exteriors to portray the

opulence and drama of the Bavarian court. The film's use of Schloss

Schleißheim was not merely for aesthetic appeal but also to lend

historical credibility to the portrayal of Ludwig II's reign. The

palace's grand halls and elaborate gardens were used to great effect,

showcasing the king's known affinity for extravagant architecture and

art. Another notable film is The Three Musketeers (1973), directed by Richard Lester who of course was responsible for A Hard Day's Night and How I Won The War.

Whilst primarily set in France, Schloss Schleißheim stood in for

several French locations, including the Louvre. The palace's Baroque

architecture convincingly doubled for 17th-century French settings,

demonstrating its versatility as a film location. The film's production

design team capitalised on the palace's authentic details, from the

ornate stucco work to the expansive gardens, to create a believable and

immersive period setting.

In more recent times, Schloss Schleißheim has been featured in The Monuments Men (2014), directed by George Clooney. This film, set during the Second World War, used the palace to represent an art repository. The choice of Schloss Schleißheim for this role was influenced by its historical association with art and culture, as well as its architectural grandeur, which lent a sense of scale and authenticity to the film's depiction of art rescue operations during the war. An earlier film that used the schloss for a WWII setting was Enemy at the Gates (2001), directed by Jean-Jacques Annaud. Although primarily set in Stalingrad, the palace was used to represent a Russian officers' club. This choice highlights the location's adaptability to various historical contexts and settings. The film's production team transformed the palace's interiors to fit the Soviet æsthetic of the 1940s, demonstrating the versatility of Schloss Schleißheim as a film location. In the film, the scenes shot here contributed to the film's portrayal of the contrast between the front-line hardships and the relative luxury of the officers' lives. The palace's opulent rooms served as a stark juxtaposition to the bleak and brutal battlefield scenes, adding a layer of visual and thematic complexity to the film which illustrates how a historical location like Schloss Schleißheim can be repurposed to fit diverse narrative needs, enhancing the film's storytelling through its unique architectural and historical attributes.

In more recent times, Schloss Schleißheim has been featured in The Monuments Men (2014), directed by George Clooney. This film, set during the Second World War, used the palace to represent an art repository. The choice of Schloss Schleißheim for this role was influenced by its historical association with art and culture, as well as its architectural grandeur, which lent a sense of scale and authenticity to the film's depiction of art rescue operations during the war. An earlier film that used the schloss for a WWII setting was Enemy at the Gates (2001), directed by Jean-Jacques Annaud. Although primarily set in Stalingrad, the palace was used to represent a Russian officers' club. This choice highlights the location's adaptability to various historical contexts and settings. The film's production team transformed the palace's interiors to fit the Soviet æsthetic of the 1940s, demonstrating the versatility of Schloss Schleißheim as a film location. In the film, the scenes shot here contributed to the film's portrayal of the contrast between the front-line hardships and the relative luxury of the officers' lives. The palace's opulent rooms served as a stark juxtaposition to the bleak and brutal battlefield scenes, adding a layer of visual and thematic complexity to the film which illustrates how a historical location like Schloss Schleißheim can be repurposed to fit diverse narrative needs, enhancing the film's storytelling through its unique architectural and historical attributes.

Such

examples illustrate how Schloss Schleißheim's architectural and

historical attributes have been effectively utilised in film. The palace

serves not just as a backdrop but as a character in itself, adding

depth and authenticity to the cinematic narrative. Its versatility as a

location, able to represent different periods and settings, makes it a

valuable asset in the filmmaker's toolkit. Nowhere was this better seen

than in Kubrick's

'Paths of Glory' with Kirk Douglas, with

the schloß serving as the French Army Headquarters. Considered one of the best anti-war films ever,

it in fact only casually discusses the cruelty and futility of the war.

An anti-militarist film, above all it is a bitter parable on governance

structures and a commitment against the death penalty. On the left is Kubrick and Douglas in front of the palace with me at the site today. On the occasion of Douglas's hundredth birthday in 2016, the legendary actor spoke of what he described his “peculiar” friendship with Kubrick

stating how “[h]e was a bastard! But he was a talented, talented guy.”

Their partnership began in 1955, when Douglas hired Kubrick to direct

the film “Paths of Glory and it didn't take long for the two to begin

clashing, a result of Kubrick having made major script rewrites without

Douglas’ approval or knowledge. In the end, Douglas forced the director

to use the original version. “Difficult? [Kubrick] invented the word,”

Douglas complained.

.gif) In

"Paths of Glory," the use of schloss Schleißheim extended beyond mere

aesthetics to become a narrative device that underscores the film's

critique of the class divisions and moral corruption within the military

hierarchy. Like Enemy at the Gates mentioned earlier, the palace's

luxurious setting starkly contrasts with the squalid conditions of the

trenches, highlighting the disparity between the decision-makers and

those who bear the consequences of their decisions. This contrast is not

just visual but also thematic, as Kubrick uses the palace to symbolise

the detachment and privilege of the upper echelons of the military. The

courtroom scene in the schloss is particularly significant as the

grandeur of the setting, with its high ceilings and elaborate décor,

serves to intimidate and dwarf the accused soldiers, emphasizing their

powerlessness in the face of military authority. Kubrick's camera work,

featuring long, uninterrupted takes, navigates through the palace's

interiors, capturing the opulence that surrounds the military elite.

This visual strategy effectively conveys the emotional and psychological

distance between the generals and the soldiers, reinforcing the film's

critique of the dehumanising aspects of war.

In

"Paths of Glory," the use of schloss Schleißheim extended beyond mere

aesthetics to become a narrative device that underscores the film's

critique of the class divisions and moral corruption within the military

hierarchy. Like Enemy at the Gates mentioned earlier, the palace's

luxurious setting starkly contrasts with the squalid conditions of the

trenches, highlighting the disparity between the decision-makers and

those who bear the consequences of their decisions. This contrast is not

just visual but also thematic, as Kubrick uses the palace to symbolise

the detachment and privilege of the upper echelons of the military. The

courtroom scene in the schloss is particularly significant as the

grandeur of the setting, with its high ceilings and elaborate décor,

serves to intimidate and dwarf the accused soldiers, emphasizing their

powerlessness in the face of military authority. Kubrick's camera work,

featuring long, uninterrupted takes, navigates through the palace's

interiors, capturing the opulence that surrounds the military elite.

This visual strategy effectively conveys the emotional and psychological

distance between the generals and the soldiers, reinforcing the film's

critique of the dehumanising aspects of war. .gif) Moreover,

Schloss Schleißheim's historical resonance as a site of power and

decision-making adds a layer of authenticity to the film. The palace,

with its history of hosting Bavarian royalty and nobility, becomes a

fitting backdrop for scenes depicting the machinations and deliberations

of military leaders. This historical authenticity enhances the film's

realism, making the viewer's engagement with the narrative more profound

and thought-provoking. Kubrick's use of Schloss Schleißheim in Paths

of Glory demonstrates the director's skill in employing historical

locations to deepen the thematic impact of his films. The palace is not

just a backdrop but an active participant in the storytelling, its

architecture and history contributing significantly to the film's

exploration of themes such as authority, morality, and the human cost of

war. The inclusion of Schloss Schleißheim in this classic film

exemplifies how a historical location can be transformed into a powerful

cinematic tool, enriching the narrative and leaving a lasting

impression on the audience.

Moreover,

Schloss Schleißheim's historical resonance as a site of power and

decision-making adds a layer of authenticity to the film. The palace,

with its history of hosting Bavarian royalty and nobility, becomes a

fitting backdrop for scenes depicting the machinations and deliberations

of military leaders. This historical authenticity enhances the film's

realism, making the viewer's engagement with the narrative more profound

and thought-provoking. Kubrick's use of Schloss Schleißheim in Paths

of Glory demonstrates the director's skill in employing historical

locations to deepen the thematic impact of his films. The palace is not

just a backdrop but an active participant in the storytelling, its

architecture and history contributing significantly to the film's

exploration of themes such as authority, morality, and the human cost of

war. The inclusion of Schloss Schleißheim in this classic film

exemplifies how a historical location can be transformed into a powerful

cinematic tool, enriching the narrative and leaving a lasting

impression on the audience.  With

this film Kubrick achieved the final international breakthrough.

Kubrick initially struggled to find a production company for the project

until Kirk Douglas agreed to star in and produce the film with his own

company Bryna and support from United Artists.

With

this film Kubrick achieved the final international breakthrough.

Kubrick initially struggled to find a production company for the project

until Kirk Douglas agreed to star in and produce the film with his own

company Bryna and support from United Artists.

The film was made between March and May 1957 in the Bavaria Film Studios Geiselgasteig and here in Schloss Schleißheim with the battle scenes filmed in a field near Puchheim. It was during the filming that Kubrick met his future third wife Susanne Christiane Harlan, who sings he German folk song The Faithful Hussar in

the final scene. At first, scriptwriter Jim Thompson had developed a

softer, positive ending in which General Broulard pardoned Dax at the

last second and punished the three soldiers with only thirty days imprisonment instead

of execution. Kirk Douglas and the third scriptwriter Calder Willingham

convinced Kubrick, however, to give the film a negative and thus

commercially less promising, but more credible end. The soldiers were supplied by 9,733 conscripts who had been born in 1937. Although

they could handle weapons, they sprang from the trenches far too

cautiously and heroically. On September 18, 1957, the film premièred in

Munich.

|

| Drake Winston standing in for Kirk Douglas |

The French had their noses out of joint and whilst

the movie was never officially banned by them, as similar massive protests were

expected from military personnel and, on the other hand, students

demonstrating against the Algerian war, as in Belgium (which often led

to performance stops in Brussels), no attempt was made by the

distributor to submit it to the censorship authority. The

title sequence of the film is underlaid at the beginning with the

Marseillaise. However, when the French government protested against the

use of the national anthem, it was replaced by percussion instruments in

countries considered particularly Francophile. In the French sector of Berlin, the responsible city commander issued in June 1958 a performance ban. He also threatened to withdraw the French festival contributions from the Berlin International Film Festival if Paths of Glory were

to be shown in West Berlin cinemas during the festival. Governing Mayor

Willy Brandt publicly described this as a "step back to 1948". After

appeals by the Berlin Senate, United Artists finally took the film from

the festival programme. Provided with an embarrassing preface stating

how the incidents shown in the film were not to be considered

representative of the army or the people of France, the film was allowed

to finally première in November in the French sector.

The French had their noses out of joint and whilst

the movie was never officially banned by them, as similar massive protests were

expected from military personnel and, on the other hand, students

demonstrating against the Algerian war, as in Belgium (which often led

to performance stops in Brussels), no attempt was made by the

distributor to submit it to the censorship authority. The

title sequence of the film is underlaid at the beginning with the

Marseillaise. However, when the French government protested against the

use of the national anthem, it was replaced by percussion instruments in

countries considered particularly Francophile. In the French sector of Berlin, the responsible city commander issued in June 1958 a performance ban. He also threatened to withdraw the French festival contributions from the Berlin International Film Festival if Paths of Glory were

to be shown in West Berlin cinemas during the festival. Governing Mayor

Willy Brandt publicly described this as a "step back to 1948". After

appeals by the Berlin Senate, United Artists finally took the film from

the festival programme. Provided with an embarrassing preface stating

how the incidents shown in the film were not to be considered

representative of the army or the people of France, the film was allowed

to finally première in November in the French sector. In

this scene one can see how Kubrick often creates a harsh dichotomy

between the misery on the front to the luxury of baroque castles. The

narrowness of the trenches is in contrast to the vastness of old

castles. When shooting this scene Kubrick used high-key technology in

which the lighting is surprisingly bright. On the checkerboard-like

floor where the court martial is held, the actors act like playing

pieces. In contrast the dark prison, filmed in the stable of the castle,

was filmed with few bright hatches sharp contrasting contrasts. The

judgement of the judges in the procedure is left out, instead a black

aperture appears. This same ballroom later transforms after the trial

into the place where General Broulard, together with other high-ranking

people, celebrates a splendid ballnight.

In

this scene one can see how Kubrick often creates a harsh dichotomy

between the misery on the front to the luxury of baroque castles. The

narrowness of the trenches is in contrast to the vastness of old

castles. When shooting this scene Kubrick used high-key technology in

which the lighting is surprisingly bright. On the checkerboard-like

floor where the court martial is held, the actors act like playing

pieces. In contrast the dark prison, filmed in the stable of the castle,

was filmed with few bright hatches sharp contrasting contrasts. The

judgement of the judges in the procedure is left out, instead a black

aperture appears. This same ballroom later transforms after the trial

into the place where General Broulard, together with other high-ranking

people, celebrates a splendid ballnight.  The

Großer Saal before and after the war, heavily damaged, and today with

the wife. The room stands as the centrepiece of the New Schleißheim

Palace, a testament to the grandeur of Baroque architecture and the

political aspirations of its patron, Maximilian II Emanuel, Elector of

Bavaria. This hall, spanning the entire width of the palace, is not

merely a physical space but a canvas for political expression and

artistic innovation. The ceiling of the Great Hall is adorned with a

series of frescoes, completed around 1726, by Johann Baptist Zimmermann,

a renowned artist of the Bavarian Baroque period. These frescoes aren't mere decorative elements; they are imbued with deep political and

allegorical meanings, crafted to glorify and legitimise the reign of

Maximilian II Emanuel. The central fresco, an awe-inspiring piece,

depicts a congregation of Olympian gods, a clear allusion to the divine right and celestial favour that the Elector sought to associate with his

rule. This portrayal of divine entities in the realm of a secular ruler

was a common theme in Baroque art, reflecting the intertwining of the

sacred and the profane in the political discourse of the time.

The

Großer Saal before and after the war, heavily damaged, and today with

the wife. The room stands as the centrepiece of the New Schleißheim

Palace, a testament to the grandeur of Baroque architecture and the

political aspirations of its patron, Maximilian II Emanuel, Elector of

Bavaria. This hall, spanning the entire width of the palace, is not

merely a physical space but a canvas for political expression and

artistic innovation. The ceiling of the Great Hall is adorned with a

series of frescoes, completed around 1726, by Johann Baptist Zimmermann,

a renowned artist of the Bavarian Baroque period. These frescoes aren't mere decorative elements; they are imbued with deep political and

allegorical meanings, crafted to glorify and legitimise the reign of

Maximilian II Emanuel. The central fresco, an awe-inspiring piece,

depicts a congregation of Olympian gods, a clear allusion to the divine right and celestial favour that the Elector sought to associate with his

rule. This portrayal of divine entities in the realm of a secular ruler

was a common theme in Baroque art, reflecting the intertwining of the

sacred and the profane in the political discourse of the time.  |

| After its bombing and today |

Surrounding

this central piece are various scenes that skilfully intertwine

mythological themes with historical events. These scenes serve as a

narrative device, elevating the status of the Elector by placing his

reign within a mythic context. The use of perspective and trompe-l'oeil

techniques in these frescoes creates an illusion of depth, adding a

sense of dynamism and vitality to the hall. This artistic approach was a

hallmark of Baroque ceiling painting, aiming to blur the boundaries

between reality and artifice, thus enhancing the viewer's experience. The

stucco work that frames these frescoes as seen in particular here on

the left with Kirk Douglas is another element of artistic merit. Gilded

and intricately designed, it complements the grandeur of the frescoes.

The play of light, both natural and artificial, on these gilded surfaces

creates a luminous effect, further accentuating the hall's opulence.

During evening events, the strategic placement of candles and

chandeliers would have highlighted specific elements of the frescoes and

stucco work, transforming the hall into a spectacle of light and

shadow.

The

floor of the Great Hall, often overlooked, is an integral part of its

design and was a particular feature in another film, again featuring The Three Musketeers (2011), when it served as the office of Christoph Waltz's Cardinal Richelieu as seen here on the right. .gif) Featuring

intricate patterns, it harmonises with the artistic narrative unfolding

above. This attention to detail is a testament to the comprehensive

approach of Baroque design, where every element of a space is considered

part of the overall artistic expression. From an architectural

standpoint, the Great Hall is a marvel. Its vast open space was a

significant engineering challenge, requiring careful planning to ensure

structural integrity. This architectural feat is not just a reflection

of the technical skills of the period but also an embodiment of the

Baroque principle of Gesamtkunstwerk, where architecture, painting, and

sculpture are integrated to create a unified artistic experience. As a

space for social gatherings, diplomatic receptions, and courtly events,

the Great Hall was central to the political and cultural life of the

Electorate of Bavaria. It was here that Maximilian II Emanuel would have

hosted dignitaries, showcasing the power and sophistication of his

court. The hall, therefore, was not just a space of aesthetic pleasure

but a tool of political diplomacy and cultural display.

Featuring

intricate patterns, it harmonises with the artistic narrative unfolding

above. This attention to detail is a testament to the comprehensive

approach of Baroque design, where every element of a space is considered

part of the overall artistic expression. From an architectural

standpoint, the Great Hall is a marvel. Its vast open space was a

significant engineering challenge, requiring careful planning to ensure

structural integrity. This architectural feat is not just a reflection

of the technical skills of the period but also an embodiment of the

Baroque principle of Gesamtkunstwerk, where architecture, painting, and

sculpture are integrated to create a unified artistic experience. As a

space for social gatherings, diplomatic receptions, and courtly events,

the Great Hall was central to the political and cultural life of the

Electorate of Bavaria. It was here that Maximilian II Emanuel would have

hosted dignitaries, showcasing the power and sophistication of his

court. The hall, therefore, was not just a space of aesthetic pleasure

but a tool of political diplomacy and cultural display.

.gif) Featuring

intricate patterns, it harmonises with the artistic narrative unfolding

above. This attention to detail is a testament to the comprehensive

approach of Baroque design, where every element of a space is considered

part of the overall artistic expression. From an architectural

standpoint, the Great Hall is a marvel. Its vast open space was a

significant engineering challenge, requiring careful planning to ensure

structural integrity. This architectural feat is not just a reflection

of the technical skills of the period but also an embodiment of the

Baroque principle of Gesamtkunstwerk, where architecture, painting, and

sculpture are integrated to create a unified artistic experience. As a

space for social gatherings, diplomatic receptions, and courtly events,

the Great Hall was central to the political and cultural life of the

Electorate of Bavaria. It was here that Maximilian II Emanuel would have

hosted dignitaries, showcasing the power and sophistication of his

court. The hall, therefore, was not just a space of aesthetic pleasure

but a tool of political diplomacy and cultural display.

Featuring

intricate patterns, it harmonises with the artistic narrative unfolding

above. This attention to detail is a testament to the comprehensive

approach of Baroque design, where every element of a space is considered

part of the overall artistic expression. From an architectural

standpoint, the Great Hall is a marvel. Its vast open space was a

significant engineering challenge, requiring careful planning to ensure

structural integrity. This architectural feat is not just a reflection

of the technical skills of the period but also an embodiment of the

Baroque principle of Gesamtkunstwerk, where architecture, painting, and

sculpture are integrated to create a unified artistic experience. As a

space for social gatherings, diplomatic receptions, and courtly events,

the Great Hall was central to the political and cultural life of the

Electorate of Bavaria. It was here that Maximilian II Emanuel would have

hosted dignitaries, showcasing the power and sophistication of his

court. The hall, therefore, was not just a space of aesthetic pleasure

but a tool of political diplomacy and cultural display.

The

room serves to glorify Max Emanuel as elector and victorious general

against the Turks. On either side of the room are two paintings by Franz

Joachim Beich showing the military exploits of Max Emanuel. The stucco

decoration by Johann Baptist Zimmermann featuring draperies, weapons and

trophies date from 1722. The ceiling is by Venetian Jacopo Amigoni

showing the "Battle of Aeneas and Turnus for the hand of princess

Lavinia" from which Aeneas emerges victorious- a metaphorical nod to Max

Emanuel who too frequently found himself in exile. The room extends

over two storeys in the middle of the main building and is flooded with

window light from both sides. The stucco is by Johann Baptist Zimmermann

based on the designs of Joseph Effner.

Standing in the Viktoriensaal, adjacent to the Great Hall, looking towards Jacopo Amigoni's painting Max Emanuel Receiving the Turkish Ambassadors (1721-1722). The room's additional ten battle scenes of Max Emanuel during the Turkish Wars of 1683-88 by Beich were created between 1720-1725. Both their rich detail and Beich's

conscientiousness- he even visited the scenes of battles- make the

paintings a valuable source of military knowledge. Surrounding the room

from above are sculpted Hercules busts designed by Robert de Cotte with

putti reliefs by Dubut. Considered one of the most beautiful interior decorations of the Baroque period,

its three narrow high wall cupboards, which are embedded in the eastern

wall, used to contain Turkish flags captured at the time by the

Elector. The Viktoriensaal also served as a dining room. Its ceiling

fresco "Dido receives Aeneas" was also painted by Amigoni and shows

Æneas exiled from burning Troy being received by Queen Dido of Carthage

whilst in the sky Venus, accompanied by cupids, forges a love affair. It

has been argued that Max Emanuel primarily commissioned these paintings

as a means of whitewashing the political mistakes that he had made

during the War of the Spanish Succession, instead strategically focusing

his contemporaries' attention on his earlier conquests over the Turks

and away from his former, scandalous alliance with the French, which had

caused him to be banned from the Empire and forced him into exile in

Belgium and France. Besides serving the Elector's propagandistic

political aims, Amigoni's pictorial program equally expressed Max

Emanuel's life-long dynastic goals of attaining Bavarian kingship and

advancing the claims of the Wittelsbach House to the Imperial throne.

Whilst the Elector's motivations in commissioning these paintings spoke

to his own specific concerns, they broadly evolved alongside

contemporary French and Austrian diplomatic relations with the Ottoman

Empire.

The

Great Gallery before the war and today, extensively renovated. The

magnificent interior decoration was the work of well-known artists such

as Johann Baptist Zimmermann, Cosmas Damian Asam and Jacopo Amigoni. The

Gallery Rooms contain masterpieces from the European baroque era. For

its 57 metre-long layout the garden side behind the Great Hall was also

employed by Robert de Cotte. It has been restored to its original state

as much as possible during recent renovations, although its most

significant masterpieces are now exhibited in the Alte Pinakothek. The

six gilded console tables with their tabletops from Tegernsee marble are

masterpieces of the Munich court art under Elector Max Emanuel, who had

them carved from 1722-1725 by court sculptor Johann Adam Pichler to designs

by the Schleißheimer palace architect Joseph Effner for the Great

Gallery. In 1761 they were supplemented by another table pair. From the

time of Max Emanuel's grandson Elector Maximilian III. Joseph also

acquired the five monumental glass chandeliers, which are around 1.70

metres high, and have been acquired in Vienna.

The

Great Gallery before the war and today, extensively renovated. The

magnificent interior decoration was the work of well-known artists such

as Johann Baptist Zimmermann, Cosmas Damian Asam and Jacopo Amigoni. The

Gallery Rooms contain masterpieces from the European baroque era. For

its 57 metre-long layout the garden side behind the Great Hall was also

employed by Robert de Cotte. It has been restored to its original state

as much as possible during recent renovations, although its most

significant masterpieces are now exhibited in the Alte Pinakothek. The

six gilded console tables with their tabletops from Tegernsee marble are

masterpieces of the Munich court art under Elector Max Emanuel, who had

them carved from 1722-1725 by court sculptor Johann Adam Pichler to designs

by the Schleißheimer palace architect Joseph Effner for the Great

Gallery. In 1761 they were supplemented by another table pair. From the

time of Max Emanuel's grandson Elector Maximilian III. Joseph also

acquired the five monumental glass chandeliers, which are around 1.70

metres high, and have been acquired in Vienna.

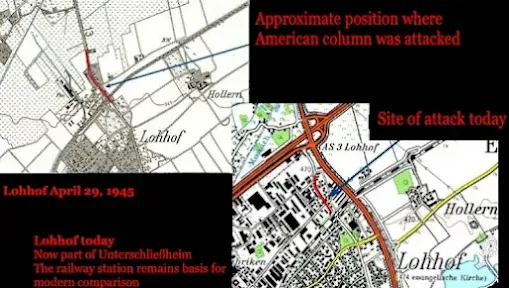

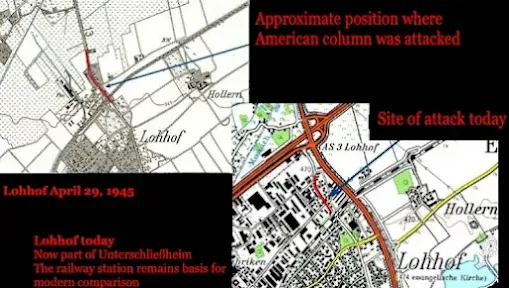

The movie also provided the setting for the enigmatic Last Year in Marienbad (1961)