These sources and questions relate to the United Nations Partition Plan, the outbreak of the civil war (1947–1948) and its results.

SOURCE A

United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) Partition Plan, 29 November 1947 (re UN Resolution 181).

SOURCE B

Extract from The Arab–Israeli Conflict by Kirsten E Schulze, 2008.

... While Zionist politicians did not like the status of Jerusalem, they accepted the UN plan as a first step to statehood. The Arabs were outraged. They could not find any redeeming aspect in a plan that allotted part of their territory to the Zionists ... Immediately following the general assembly vote, both Arabs and Jews started to arm themselves. What ensued was a civil war between Jews and Palestinian Arabs, all within Palestine. The months before the end of the mandate were characterized by bitter fighting – including the massacre at the Arab village of Deir Yassin by the Irgun and Lehi which killed 250, the Arab ambush on a Jewish medical convoy killing 75, and the Arab siege of Jerusalem – ultimately resulting in a mass exodus of Palestinian Arabs. By May 1948, when the British finally withdrew, over 300 000 Arabs had fled from what was to become the new Jewish state ... Historians have argued about the causes of this flight ever since.

SOURCE C

Extract from a report on the village of Deir Yassin by former Haganah officer, Col. Meir Pa’el, released upon his retirement from the Israeli army in 1972. This report was written in 1948.

In the exchange that followed four [Irgun] men were killed and a dozen were wounded ... by noon the battle was over and the shooting had ceased. Although there was calm, the village had not yet surrendered. The Irgun and LEHI men came out of hiding and began to “clean” the houses. They shot whoever they saw, women and children included; the commanders did not try to stop the massacre ... I pleaded with the commander to order his men to cease fire, but to no avail. In the meantime, 25 Arabs had been loaded on a truck ... and murdered in cold blood ... The commanders also declined when asked to take their men and bury the 254 Arab bodies. This unpleasant task was performed by two units brought from Jerusalem.

SOURCE D

Extract from The Revolt by Menachem Begin, 1977. Before the establishment of Israel, Begin was the leader of the Irgun. He did not participate in the battle for the village of Deir Yassin.

... The civilian population of Deir Yassin was actually given a warning by us before the battle began ... A substantial number of the inhabitants obeyed the warning and they were unhurt. Our men were compelled to fight for every house ... And the civilians who had disregarded our warnings suffered inevitable casualties. Throughout the Arab world and the world at large, a wave of lying propaganda was let loose about “Jewish atrocities” ... the Arabs began to flee in terror, even before they clashed with Jewish forces ... This Arab propaganda spread a legend of terror amongst Arabs and Arab troops, who were seized with panic at the mention of Irgun soldiers. The legend was worth half a dozen battalions to the forces of Israel. The “Deir Yassin Massacre” lie is still propagated by Jew-haters all over the world.

SOURCE E

Extract from Palestine and the Arab–Israeli Conflict by Charles D Smith, 2007. Charles D Smith was a history teacher at the University of Arizona.

The significance of Deir Yassin went far beyond its immediate fate ... it became central to Irgun and Haganah propaganda proclaimed from mobile loudspeaker units that beamed their messages into the Arab areas of major cities ... Arab radio also publicized the incident. These broadcasts had a major impact on the Arab will to resist, especially when the population found itself betrayed by its leaders. In Haifa, the Arab military command and city officials left in the face of Irgun assaults and open threats of another Deir Yassin ... Israeli officials claimed that the Arabs were encouraged to leave by Arab propagandists who promised them an easy return once their Armies defeated the Zionists. But Zionist actions reflected a definite desire to oust as many Arabs as possible ... The Zionists undertook a policy “promoting measures designed to encourage the Arab flight” and forbidding the return of those who left ... in addition to the psychological warfare and threats. These threats meant more to the Arab civilians than did the pleas of some Jews for the Arabs to remain ... For the Zionists, the vacuum created by the fleeing Arabs meant that incoming Jews could be moved into the vacant homes in towns and villages ... In this manner, a much more cohesive Jewish state with a much smaller Arab population could be achieved.

1. (a) What does Source A suggest about the United Nations Partition Plan of 1947? [3 marks]

(b) According to Source B, what were the reactions to the United Nations Partition Plan? [2 marks]

2. Compare and contrast the views expressed in Sources C and D about the incident in the village of Deir Yassin. [6 marks]

3. With reference to their origin and purpose, assess the value and limitations of Source C and Source E for historians studying the events which occurred during the civil war in Palestine between 1947 and 1948. [6 marks]

4. Using the sources and your own knowledge, analyse the reasons for the flight of the Palestinian Arabs during the civil war between 1947 and 1948. [8 marks]

November 2010

These sources and questions relate to the outbreak of the Arab–Israeli Six Day War (1967).

SOURCE A

An extract from a speech to members of the Egyptian National Assembly by Gamal Abdul Nasser, Egyptian President, 29 May 1967.

We are now ready to deal with the entire Palestine question. The issue now at hand is not the Gulf of Aqaba, the Straits of Tiran, or the withdrawal of the UNEF (United Nations Emergency Force), but the rights of the Palestine people. It is the aggression which took place in Palestine in 1948 with the collaboration of Britain and the United States. It is the expulsion of the Arabs from Palestine, the denial of their rights, and the plunder [theft] of their property. It is the disavowal [ignoring] of all the UN resolutions in favour of the Palestinian people. If the United States and Britain are partial to Israel, we must say that our enemy is not only Israel but also the United States and Britain and treat them as such.

SOURCE B

Cartoon by Imad Melhem, © Alhayat newspaper issue # 31 May 1967.

|

| Israel, represented by the Star of David, submits to the tanks of the United Arab Republic, Syria, Jordan and Lebanon. |

SOURCE C

An extract from The Origins of the Arab-Israeli Wars, Ritchie Ovendale, London, 1984. Ovendale was a lecturer in the Department of International Politics at University College, Aberystwyth, UK.

Abba Eban [Israeli Foreign Minister] returned to Tel Aviv on 23 May 1967 and attended a meeting at the Ministry of Defence: it was reported that the Egyptians were not yet ready for a full offensive; Syria was retreating; there was no movement in Jordan. Yitzhak Rabin [Chief of Staff of Israeli Defence Forces] had told him that time was needed to reinforce the south: the diplomatic establishment could help with that. Eban advised the gathering that Israel must think like a nation whose soil had already been invaded; but Israel’s predicament [problem] was international not regional and it had to look to the United States to neutralize the Russian menace. Johnson [US President] had asked to be consulted, and for forty-eight hours’ respite. Most of those present agreed on the need for a political phase before a military reaction. Moshe Dayan [Israeli Defence Minister], however, favoured military action against Egypt after forty-eight hours on a battleground close to the Israeli border. It was agreed to mobilize the reservists.

SOURCE D

An extract from The Palestine–Israel Conflict, Gregory Harms, London, 2005. Harms is a freelance writer and researcher.

Reports began to come from Damascus that the Israelis were massing troops in heavy concentration along the Syrian border, poised for imminent attack. Russia “confirmed” these reports, which escalated the tension and placed Nasser on high alert; Egypt and Syria, at Russian request, signed a defence pact that would help protect Soviet objectives in the region. The reports of massing Israeli troops, however, were false. Later Syrian reconnaissance flights provided conclusive photos that revealed no such troop concentrations, and UN observers, too, confirmed the falsity of the claim. Though reasoning behind Russian behaviour here is speculative, most assume that it feared an Israeli attack on Syria and thought a potential Egyptian response might encourage Israeli hesitation. Whether Nasser knew of the intelligence being bogus [false] or not, he began assembling troops in Sinai. Nasser’s response is also an occasion for speculation, but the intent of polishing up his image probably was not far from his mind. And then he took it the extra step. To the shock of just about everyone, Nasser requested the UNEF to withdraw from the Egyptian border and Sinai, as was his legal right according to the agreement after the Suez Crisis.

SOURCE E

An extract from Palestine and the Arab–Israeli Conflict, Charles Boston, 2007. Smith is a Professor of History at the University of Arizona.

A decisive factor was the news on June 2 that in response to American requests, Nasser had agreed to send his vice president, Zakariya Mohieddine, to Washington on June 7 to discuss measures to defuse the potential for confrontation over the Tiran blockade. This was totally unacceptable, even to Eban, who had resisted the military option until June 1: it was probable that this initiative would aim at a face-saving compromise and that the face to be saved would be Nasser’s not Israel’s ... Egyptian occupation of Sharm al-Sheikh and the blockade might be the reason to justify an attack, but Israel was also determined to deny Nasser his political triumph in the Arab world. ... With increased confidence in American acquiescence [acceptance], determined to punish Nasser and thwart the intent of Mohieddine’s forthcoming visit to Washington, the cabinet on June 4 approved Dayan’s plan to attack Egypt the next morning.

1. (a) What does Source A suggest about Nasser’s attitude towards the Palestinian question? [3 marks]

(b) What is the message conveyed by Source B? [2 marks]

2. Compare and contrast the views expressed in Sources C and E about the 1967 crisis. [6 marks]

3. With reference to their origin and purpose, assess the value and limitations of Source A and

Source D for historians studying the Arab–Israeli Six Day War (1967). [6 marks]

4. Using the sources and your own knowledge, analyse the reasons behind the outbreak of the Arab–Israeli Six Day War (1967). [8 marks]

May 2011

These sources and questions relate to the role of the United States in the Suez Crisis of 1956.

SOURCE A

Extract from A History of the Arab–Israeli Conflict by Ian J Bickerton and Carla Klausner, 2007.

During 1956, United States’ policy in the Middle East was to neutralize the Arab–Israeli conflict, convince Arabs and Israelis to join the West against the Soviets and maintain oil supplies to the West ... But Arab nationalists saw the United States as an ally of the colonial powers and a supporter of Israel ... Egypt’s president Nasser, a nationalist, wanted the removal of Western influence from the Middle East, to modernize Egypt, to promote pan-Arabism and to eradicate Israel ... Eisenhower’s Secretary of State, Dulles, offered Nasser, in return for concessions, economic aid for military equipment and to build the Aswan Dam ... Nasser, however, would not conform ... When Dulles decided not to sell Nasser arms, Nasser turned to the Soviet Union and purchased arms from Czechoslovakia, and recognized Communist China. ... Dulles withdrew United States’ support for the Aswan Dam. In retaliation, Nasser nationalized the Suez Canal to use its profits to build the dam.

SOURCE B

Extract from a letter from British prime minister Anthony Eden to Eisenhower on 27 July 1956. Taken from The Suez Crisis by Anthony Gorst and Lewis Johnman, 1997.

We cannot allow Nasser to seize control of the Canal in defiance of international agreements ... If we do, our influence and yours throughout the Middle East will be destroyed ... The Canal is vital to the free world ... the Egyptians’ complete lack of technical qualifications and their behaviour show that they cannot be trusted to manage it. ... We should not be involved in legal quibbles [quarrels] about rights to nationalize an Egyptian company, or in financial arguments about their capacity to pay the compensation. We should bring maximum political pressure to bear on Egypt and in the last resort, to use force ... the first step must be for you and us and France to exchange views and align our policies.

SOURCE C

Extract from Eisenhower and the Suez Crisis of 1956 by Cole C Kingseed, 1995.

The nationalization of the Suez Canal threatened many states ... the British saw its oil supply and strategic control of the Middle East endangered ... France saw Egypt as a supplier of arms for Algerian rebels; and a reinforcement of Nasser’s influence over North Africa ... Israel was worried about interference with their shipping rights through the canal and further encouragement of the Palestinian guerrilla campaign ... Without consulting their American ally in advance, the three countries devised and executed a plan to retaliate against Egypt ... The Soviet Union branded Britain, France and Israel as “aggressors” and threatened to intervene militarily in defense of Egypt ... Moscow contacted Washington with a view to a joint US–Soviet military operation against them. Eisenhower rejected this proposal ... Nevertheless, Eisenhower was furious, and shouted: “Tell them that we’re going to apply sanctions, we’re going to the United Nations, and we’re going to do everything that there is so we can stop this thing!”

SOURCE D

Extract from president Eisenhower’s address to the nation on 31 October 1956. Taken from The Cold War: A History Through Documents by Edward H Judge and John W Langdon, 1999.

Matters came to a crisis when the Egyptian government seized the Suez Canal ... some among our allies urged a reaction by force. We urged otherwise, and our wish prevailed, through a long succession of conferences and negotiations ... But the direct relations of Egypt with both Israel and France kept worsening to a point at which they determined that there could be no protection of their vital interests without resort to force ... The United States was not consulted in any way about any phase of these actions. ... these actions were taken in error. We do not accept the use of force for the settlement of international disputes. To say this is not to minimize our friendship with these nations ... But their action can scarcely be reconciled with the principles of the United Nations to which we have all subscribed ... Yesterday we went to the United Nations with a request that hostilities in the area be brought to a close. The proposal was vetoed by Great Britain and by France ... We intend to bring this matter before the United Nations General Assembly. There, with no veto operating, the opinion of the world can be brought to bear in our quest for a just end to this problem.

SOURCE E

A cartoon by Leslie Gilbert Illingworth, a British cartoonist, published on 1 January 1957. Leslie Gilbert Illingworth worked for Punch and the Daily Mail.

|

| “Who will catch the Middle East?” |

1. (a) What, according to Source C, were the reactions of the powers mentioned to the nationalization of the Suez Canal? [3 marks]

(b) What is the message conveyed by Source E? [2 marks]

2. Compare and contrast the views expressed in Sources B and D about the Suez Crisis. [6 marks]

3. With reference to their origin and purpose, assess the value and limitations of Source A and Source C for historians studying the Suez Crisis of 1956. [6 marks]

4. Using the sources and your own knowledge, evaluate the role played by the United States in the Suez Crisis of 1956. [8 marks]

November 2011

These sources and questions relate to the emergence of the Palestine Liberation Organization.

SOURCE A

Extract from the Palestine National Charter, July 1968.

2. Palestine, with the boundaries it had during the British Mandate, is an indivisible territorial unit.

5. The Palestinians are those Arab nationals who, until 1947, normally resided in Palestine regardless of whether they were evicted from it or have stayed there. Anyone born after that date, of a Palestinian

father – whether inside Palestine or outside it – is also a Palestinian.

9. Armed struggle is the only way to liberate Palestine. Thus it is the overall strategy, not merely a

tactical phase ...

19. The partition of Palestine in 1947 and the establishment of the state of Israel are entirely illegal,

regardless of the passage of time, because they were contrary to the will of the Palestinian people and to their natural right in their homeland, and inconsistent with the principles embodied in the Charter of the United Nations, particularly the right to self-determination.

SOURCE B

Extract from “The Birth of the Palestine Liberation Organization” by Abdel-Qader Yassin in the International Politics Journal (Al-Siyassa Al-Dawliya), April 2004. This is an Egyptian periodical specializing in political and international affairs.

National liberation movements around the world were achieving independence for their countries. The long-term strategy of a popular war, as proved successful in Korea, Cuba and Vietnam, urged Palestinian resistance groups to endorse a similar strategy. By the time Israel started to divert the course of the River Jordan in 1963, the Arab world was divided into two camps: one that considered that the Palestinians alone should shoulder the responsibility for confronting the Israelis, and the other that believed that a Palestinian organization should be formed under the auspices of [in line with] the Arab system. In 1963, Nasser endorsed the recognition of Ahmed Shukeiri as representative for Palestine in the Arab League and called for the convention of the first Arab summit in 1963, where Shukeiri was asked to present the opinions of the various Palestinian groups.

SOURCE C

Extract from The Arab–Israeli Conflict by T G Fraser, 2004. T G Fraser is a professor at the University of Ulster, UK.

Fatah’s new importance was soon reflected in a major reorganization of the PLO [Palestine Liberation Organization] in the summer of 1968. The 1964 National Charter was revised to reflect Fatah’s leadership and the strategy of guerrilla action which the PLO was now to follow. At the heart of the Charter was the claim that Palestine, as it had been constituted under the British Mandate, was “an indivisible territorial unit”. This reflected the Palestinians’ rejection of partition, which they had followed consistently since 1937, and which meant no prospect of compromise with Israel. On the contrary, articles 9 and 10 committed the organization to “armed struggle” and “commando action”. The way was now clear for Arafat to become chairman of the PLO, and for the various armed groups to be brought into its structure.

SOURCE D

Extract from “Arafat’s Legacy” by Snehal Shingavi in the International Socialist Review, 2005. Snehal Shingavi is a lecturer in Middle Eastern studies at the University of California, Berkeley.

Egyptian President Gamal Abdul Nasser’s pan-Arab nationalism was both exciting and confusing. On the one hand, by nationalizing the Suez Canal and calling for the unity of all Arab peoples against puppet regimes, it represented a bold defiance of Western imperialism. On the other hand, the break- up of the Egyptian–Syrian union in 1961 demonstrated the fragility of any pan-Arab alliance. While it was the dominant political trend, even among Palestinians until 1967, pan-Arab nationalism proved to be a hollow solution for Palestinians – occasionally supporting Palestinian concerns, at other times ignoring them. Nasser failed, for instance, to defend Palestinians from Israeli attacks, like the one in Gaza in 1955, while the defeats from the 1948 war were a constant reminder of Arab inadequacy. At the same time, the successes of the Vietnamese and Algerian resistance to the French also convinced many Palestinians that military struggle against Israel was both possible and necessary. When Nasser announced in 1962 that he had “no plan for Palestine”, thousands of Palestinians flocked to Fatah and its call for armed resistance to Zionism. In 1964, Arab countries led by Egypt, established the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) in order to divert the growing stream of Palestinian radicalism that threatened the internal stability of a number of these countries. But it had the opposite effect – giving Palestinian nationalism a larger audience and greater legitimacy.

SOURCE E

A photograph showing Yasser Arafat leaving the 5th Palestinian National Council session in Cairo in February 1969, having been elected as chairman of the Palestine Liberation Organization.

1. (a) What, according to Source C, was the significance of the reorganization of the National Charter in the summer of 1968? [3 marks]

(b) What is the message conveyed by Source E? [2 marks]

2. Compare and contrast the views expressed in Sources B and D about the emergence of the Palestine Liberation Organization. [6 marks]

3. With reference to their origin and purpose, assess the value and limitations of Source A and Source D for historians studying the emergence of the Palestine Liberation Organization. [6 marks]

4. Using the sources and your own knowledge, analyse the statement in Source D that the emergence of the Palestine Liberation Organization had given “Palestinian nationalism a larger audience and greater legitimacy” between 1960 and 1970. [8 marks]

These sources and questions relate to the October War of 1973 and its consequences.

SOURCE A

International History of the Twentieth Century by Antony Best,Jussi M. Hanhimäki, Joseph A. Maiolo and Kirsten E. Schulze, Routledge, London, 2004.

Ironically Sadat’s search for peace and willingness to negotiate with Israel led to the Arab–Israeli war of 1973. Shortly after Sadat succeeded Nasser he made contact with the Americans to test the waters [check responses] in regard to realigning Egypt with the West and negotiating with Israel. Sadat believed peace with Israel would allow him to regain the Sinai and result in a reduction of Egypt’s defence burden, create stability at home and attract foreign investment and American aid.

He proposed a ceasefire and to re-open the Suez Canal and to negotiate on the basis of resolution 242. Israel rejected these proposals and as a result Sadat started planning a war in order to persuade Israel to make peace on terms acceptable to the Arabs and in order to attract the attention of the US which was focused on Vietnam and détente at the time.

SOURCE B

|

| “You have only been slapping me on the back lately, haven’t you, Mr. Brezhnev?” |

SOURCE C

Extract from The Near East Since the First World War: A History to 1995, by M. E. Yapp, 1996. Published by Pearson Education, Harlow, Essex.

The deadlock in the near east was broken by Egypt and Syria when they attacked Israel in October 1973. Sadat had become convinced of the necessity of a limited war to persuade Israel to make peace on terms that would be acceptable to the Arab world and to persuade the world to support a peace settlement. Egypt was supported by Syria in the Golan Heights ... and Saudi Arabia agreed to support an oil embargo.

During the first three days the war went well, Egypt seized the east bank of the Suez Canal and Syria broke through in the Golan. Then Israel recovered; Syrian forces were pushed back and Egyptian forces were in danger of being cut off by the Israeli advance. During the course of the 1973 war both superpowers had supported their client states with fresh supplies of arms and diplomatic support. But they had also agreed on concerted [joint] action through the UN to achieve a ceasefire.

SOURCE D

A History of the Arab Peoples by Albert Hourani, Faber & Faber, London, 1992.

In October 1973 Egypt launched a sudden attack on Israeli forces on the east bank of the Suez Canal at the same moment, by agreement, the Syrians attacked Israel. The Egyptian army succeeded in establishing a bridgehead on the east bank and the Syrians occupied parts of the Jawlan.

In the next few days the military tide turned, Israeli forces crossed the canal and also drove the Syrians back towards Damascus. Their success was due to equipment sent by the Americans and partly due to policy differences between Egypt and Syria ...

But neither in the eyes of the Arabs nor those of the world did the war seem to be a defeat. They had attracted sympathy and financial and military help from other Arab countries, it ended in a ceasefire imposed by the superpowers which showed that while the US would not allow Israel to be defeated neither would it or the USSR allow Egypt to be defeated.

SOURCE E

The Security Council:

1. calls upon all parties to the present fighting to cease all firing and terminate all military activity

immediately, no later than 12 hours after the adoption of this decision; in the positions they now occupy.

2. calls upon the parties concerned to start immediately after the ceasefire the implementation of Security Council resolution 242 in all of its parts.

3. decides that, immediately and concurrently with the ceasefire, negotiations start between the parties concerned under the appropriate auspices aimed at establishing a just, durable peace in the Middle East.

1. (a) What does Source A reveal about Sadat’s reasons for attacking Israel in October 1973? [3 marks]

(b) What is the message conveyed by Source B? [2 marks]

2. Compare and contrast the views expressed in Sources C and D about the events of October 1973. [6 marks]

3. With reference to their origin and purpose, assess the value and limitations of Source A and Source E for historians studying the October War of 1973. [6 marks]

4. Using the sources and your own knowledge, to what extent do you agree that Sadat achieved his aims in going to war in 1973? [8 marks]

November 2012

These sources and questions relate to Camp David and the Egyptian-Israeli Peace Agreement.

SOURCE A

Extract from a speech by Andrei Gromyko, Soviet Foreign Minister, given at the United Nations General Assembly, 25 September 1979.

The separate deal between Egypt and Israel resolves nothing. It is a way of piling up, on a still greater scale, explosive material capable of producing a new conflict in the Middle East. Moreover, added to the tense political atmosphere in this and the neighbouring areas is the heavy smell of oil.

It is high time that all states represented in the United Nations realized how vast the tragedy of the Arab peoples of Palestine is. What is the worth of declarations in defence of human rights – whether for refugees or not – if before the eyes of the entire world the basic rights of an entire people driven from its land and deprived of a livelihood are ignored?

The Soviet policy with respect to the Middle East problem is one of principle. We are in favour of a comprehensive and just settlement, of the establishment of a durable peace in the Middle East, a region not far from our borders. The Soviet Union sides firmly with Arab peoples who resolutely reject deals at the expense of their legitimate interests.

SOURCE B

Extract from Palestine: Peace not Apartheid by Jimmy Carter, 2007. Jimmy Carter was US president between 1976 and 1980 and a key figure in the negotiations at Camp David.

Anwar Sadat withstood the condemnation of his fellow Arabs, who imposed severe though ultimately unsuccessful diplomatic, economic, and trade sanctions against Egypt in an attempt to isolate and punish him. Until much later, long after I left public office, neither the Jordanians nor the PLO were willing to participate in subsequent peace talks with Israel. This confirmed the Israelis’ fears that their nation’s existence would again be threatened as soon as their enemies could build up enough strength to mount an attack.

For Menachem Begin, the peace treaty with Egypt was the significant act for Israel, while solemn promises regarding the West Bank and Palestinians would be ignored or deliberately violated. With the bilateral treaty, Israel removed Egypt’s considerable strength from the military equation of the Middle East and thus it permitted itself renewed freedom to ... confiscate, settle and fortify the occupied territories.

[Extract from: Jimmy Carter (2007) Palestine: Peace not Apartheid, Simon and Schuster, New York.]

SOURCE C

Extract from the article ‘From June 1967 to June 1997: Learning from our mistakes’ by Clovis Maksoud, Arab Studies Quarterly, 1997. Clovis Maksoud is the former Ambassador of the League of Arab States to the United Nations and the United States.

In the 1980s, the Arab world was shocked by a series of traumatic developments that worsened the already existing complex conditions. Besides the 1978 visit of President Sadat to Jerusalem, which led to the peace treaty between Egypt and Israel, the fall of the Shah of Iran, and the victory of the Islamic Revolution in Iran, there was a renewal of inter-Arab disputes and conflicts. With Egypt’s suspension from the League of Arab States a vacuum was created which nearly paralyzed Arab cooperation, let alone Arab unity. The coincidence of Egypt’s peace treaty with Israel and the occurrence of the Islamic Revolution in Iran had a decidedly deep impact on the Arab world in the eighties. The two developments tended to pull the region apart.

SOURCE D

Extract from Waging Peace by Itamar Rabinovich, 2004. Itamar Rabinovich is the former Israeli ambassador to the United States 1993 to 1996.

The Camp David Accords turned Arab–Israeli diplomacy into a full-blown effort to achieve peace. By extending diplomatic recognition to Israel, signing a peace treaty with it, and establishing normal relations with it, Sadat and Egypt violated a taboo that an Arab consensus had strictly enforced for more than three decades. There were two parts to the Camp David Accords – an Israeli Egyptian agreement terminating the bilateral dispute between them, and a framework laying down the principles for resolving Israel’s conflict over the Palestinians and its disputes with other Arab neighbours. But the two parts were not of equal importance. Begin and Sadat were primarily interested in their bilateral agreement, and both leaders saw to its strict implementation. Indeed, this was how the Arab world perceived the agreements: as Sadat’s having betrayed them and made a separate peace with Israel. He was denounced and condemned, Egypt was expelled from the Arab League, and most Arab states cut off diplomatic relations with Cairo.

[Itamar Rabinovich (2004) Waging Peace, Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ.]

SOURCE E

Cartoon by Felix Mussil, a German cartoonist, on the Camp David Accords, March 1979.

|

| Anwar Sadat Jimmy Carter Menachem Begin |

(b) What is the message conveyed by Source E? [2 marks]

2. Compare and contrast the views expressed in Sources C and D about Camp David and the Egyptian-Israeli Peace Agreement. [6 marks]

3. With reference to their origin and purpose, assess the value and limitations of Source A and Source B for historians studying Camp David and the Egyptian-Israeli Peace Agreement. [6 marks]

4. Using the sources and your own knowledge, analyse the significance of the Egyptian-Israeli Peace Agreement and events in the Middle East for Israel and the Arab World up to the end of 1979. [8 marks]

May 2013

These sources and questions relate to problems after the 1948/49 conflict and the Arab response.

SOURCE A

Extract from The History of the Modern Middle East by W Cleveland, 2009. W Cleveland is a former professor at Simon Fraser University, Canada.

The 1948–1949 exodus of the Arab population, created a refugee problem of immense proportions. The refugees lived in makeshift camps in Jordan, Lebanon, Syria and the Gaza Strip. The camps had been set up as temporary shelters pending a solution to the refugee problem. The solution envisaged at the time was the repatriation [return] of the refugees to the areas from which they had fled. However actions taken by the Israeli government in the years immediately after 1948 made this unlikely. The Israeli authorities, faced with a wave of Jewish immigration totalling more than 600000 between 1948 and 1951, took over vacant Palestinian villages, urban dwellings and farmland to house and feed the immigrants. The absorption of Palestinian property into the Israeli economy made it next to impossible for Israel to consider repatriation. Destitute and uprooted, the majority of Palestinians had no alternative to the miserable conditions of camp life.

SOURCE B

Photograph of a Palestinian Refugee Camp in Jordan 1949, published in the school textbook Crisis in the Middle East: Israel and the Arab States 1945–2007 by M Scott-Baumann, 2009.

SOURCE C

United Nations General Assembly Resolution 393, 2 December 1950.

The General Assembly, having examined the report of the United Nations Relief and Works Agency

(UNRWA) for Palestine refugees:

1. notes that contributions sufficient to carry out the programme have not been made and urges governments to make every effort to make a voluntary contribution ...;

2. recognizes that direct relief cannot be terminated;

3. authorizes the agency to continue direct relief to refugees, and considers that for the period July

1951–June 1952 approximately $20000000 will be required for relief to refugees who are not yet

reintegrated into the economy of the Near East;

4. instructs the Agency to establish a reintegration fund to support projects for the permanent

re-establishment of refugees and their removal from relief;

5. considers that approximately $30000000 should be contributed to the agency for this purpose ... for

the period July 1951–June 1952;

6. thanks the numerous religious, charitable and humanitarian organizations who have brought much

needed supplementary [extra] assistance and urges them to continue and expand their work.

SOURCE D

Extract from The Palestine–Israeli Conflict: a Beginner’s Guide, by Professor Dan Cohn-Sherbok and Dr Dawoud El-Alami (2009).

In January 1949 Egypt began negotiations for an armistice agreement with the Israelis and signed an agreement in February. This was to form the basis of a peace agreement. The borders were drawn along the lines marking the existing positions of the armies. Lebanon, Jordan and Syria signed armistice treaties the same year.

The main issue was the refugee problem. A reconciliation committee was formed and Arab and Israeli delegates were invited to Lausanne to discuss important issues, particularly the refugee problem. The Arabs stated that the return of the refugees would be the basis for establishing peace in the area. The Israelis felt this issue should be suspended until a final peace agreement was made. The Israeli delegates agreed, however, to support a protocol consisting of three main principles:

1. respect for the boundaries agreed in the partition plan;

2. consent to Jerusalem becoming an independent city;

3. the return of the refugees and the restoration of their property.

The Arab parties agreed to the protocol and signed it on 12 May 1949; on the same day Israel became a member of the United Nations.

SOURCE E

Extract from The Iron Wall: Israel and the Arab World, by Avi Shlaim, 2000. Avi Shlaim is a Professor of International Relations at Oxford University, UK.

The two key issues were refugees and borders. Each of the Arab states was prepared to negotiate with Israel from September 1948 and bargain about borders.

On the issue of Palestinian refugees, Arab states had less freedom of action. There was a clear and consistent Arab League position, binding on all members. The position was that Israel had created the refugee problem and it must not be allowed to evade responsibility for the problem. The solution had to be in line with UN resolutions that gave the refugees the choice between returning to their homes or receiving compensation for their property. This position allowed individual Arab states to cooperate with the United Nations Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA), on condition that this cooperation did not compromise [undermine] the basic rights of the refugees.

Israel’s position on the problem was totally opposed to the Arab League’s. Israel claimed the Arabs had created the problem by starting the war and that Israel was not responsible. It did not accept UN resolutions that gave refugees the right of return or compensation.

1. (a) What does Source A reveal about the situation of Palestinian refugees immediately after the 1948/49 conflict and the Arab response? [3 marks]

(b) What is the message conveyed by Source B? [2 marks]

2. Compare and contrast the views expressed in Sources D and E about the peacemaking process after the first Arab–Israeli conflict. [6 marks]

3. With reference to their origin and purpose, assess the value and limitations of Source B and Source C for historians studying the Arab–Israeli conflict. [6 marks]

4. Using the sources and your own knowledge, analyse the importance of the Palestinian refugee question in the peacemaking process after the 1948/49 war up until the 1967 conflict. [8 marks]

November 2013

These sources and questions relate to the Suez Crisis of 1956.

SOURCE A

Extract from The Suez Crisis, 1956 from The Office of the Historian, United States Department of State, 2012. The authors are experts on the history of US foreign policy.

On 29 October 1956, Israeli forces moved across the border, defeated the Egyptian army in the Sinai, captured Sharm el-Sheikh and thereby guaranteed Israeli strategic control over the Straits of Tiran. Britain and France issued their ultimatum and landed troops, effectively carrying out the agreed upon operation. However, the United States and the Soviet Union responded to events by demanding a ceasefire. In a resolution before the United Nations, the United States also called for the evacuation of Israeli, French, and British forces from Egypt under the supervision of a special United Nations force. This force arrived in Egypt in mid-November. By 22 December, the last British and French troops had withdrawn from Egyptian territory, but Israel kept its troops in Gaza until 19 March 1957, when the United States finally compelled the Israeli government to withdraw its troops. The Suez conflict fundamentally altered the regional balance of power. It was a military defeat for Egypt, but Nasser’s status grew in the Arab world as the defender of Arab nationalism.

SOURCE B

Cartoon by Fritz Behrendt published in the German newspaper Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, 1956, depicting the situation after the Suez Crisis

The Man at the Tap

SOURCE C

Extract from Arafat – The Biography by Tony Walker and Andrew Gowers, 2003. Tony Walker is political editor of the Australian Financial Review and Andrew Gowers was Middle East editor of the London Financial Times from 1987 to 1990. Walker and Gowers are both journalists.

International pressure forced a ceasefire at midnight on 6 November and Nasser emerged a towering hero in the Arab world. He had defied the power of Britain and France, not to mention Israel. It was a “victory” that seemed to Arafat and his colleagues could benefit the Palestinian cause, but they discovered nothing could have been further from the truth. After his triumph over the tripartite aggression, Nasser cracked down even harder on the Muslim Brotherhood and anyone else he considered a threat to public order. Student activists who had flirted with the Muslim Brotherhood were among those kept under close surveillance. The Egyptian secret police had, in any case, long been taking a close interest in Arafat’s activities.

SOURCE D

Extract from The Arab–Israeli Wars by Chaim Herzog, 2004. Chaim Herzog was president of Israel from 1983 to 1993 and was a high ranking officer in the Israeli

army until 1962.

In Gaza, the withdrawal of the Israeli forces led to a period of violence in which those who had allegedly “cooperated” with the Israeli occupying forces, from November 1956 until the Israeli withdrawal in March 1957, were summarily executed. The United Nations soldiers in the Gaza Strip lost all control of the roaming fedayeen gangs, and indeed of the entire situation. Within two days of Gaza being transferred to the United Nations, Nasser had nominated a military governor for the Gaza Strip who, without asking the UN, moved in with his headquarters – the United Nations did not even complain, and this weakness sowed the seeds for future problems in the area. Within a short time, the Mayor of Gaza was dismissed and replaced by a pro-Egyptian. At the same time, the UN, under pressure from the Egyptians, ordered its forces to leave the Gaza Strip and only patrol its borders. The UN Emergency Force took up positions along the borders between Israel and Egypt, and at Sharm el-Sheikh.

SOURCE E

Extract from “Consequences of the Suez Crisis in the Arab World” by Rashid Khalidi, in The Modern Middle East: A Reader by Albert Hourani, et al, 1993. Rashid Khalidi is professor of Arab Studies at Columbia University, US, and was a personal friend of Arafat in the 1980s.

Beyond its effect on Egypt and the other direct participants, the Suez Crisis had a profound effect on the rest of the Arab world ... Suez firmly established Nasser as the pre-eminent Arab leader until the end of his life, and Arab nationalism as the leading Arab ideology for at least that long. Suez also ended the dominant influence over the Arab world which Britain and France had sometimes shared and sometimes disputed for over a century ... Arab leaders ceased paying attention to London and Paris, turning to Cairo, Washington, and Moscow. Finally, because it involved Israel in open collaboration with the old imperial powers and in an invasion of the territory of an existing Arab state, the Suez Crisis established an image of Israel in the Arab world, and a pattern of conflict with it, that had an impact perhaps as important as the 1948 war.

1. (a) What, according to Source C, were the immediate consequences of the Suez Crisis? [3 marks]

(b) What is the message conveyed by Source B? [2 marks]

2. Compare and contrast the views expressed in Sources A and E about the Suez Crisis of 1956. [6 marks]

3. With reference to their origin and purpose, assess the value and limitations of Source C and Source D for historians studying the Suez Crisis of 1956. [6 marks]

4. Using the sources and your own knowledge, analyse the consequences of the Suez Crisis for the countries involved up to the end of 1959. [8 marks]

May 2014

These sources and questions relate to the role of the United States in the Middle East (1973–1978).

SOURCE A

Extract from “The Cold War in the Middle East: Suez Crisis to Camp David Accords” by D Little, in The Cambridge History of the Cold War, Volume 2: Crises and Détente, 2010. D Little is an American professor of History.

Throughout the fall [autumn] of 1973 and into the new year Kissinger solidified his unofficial contacts with Anwar Sadat, who quickly concluded that the road to resolution of the Egyptian–Israeli conflict ran through Washington not Moscow. Relying on what came to be known as “shuttle diplomacy”, Kissinger pressed both Tel Aviv and Cairo, step by reluctant step towards a disengagement agreement in the Sinai and then raised the possibility of a broader peace settlement. Kissinger’s breakthrough on the Egyptian–Israeli front was a crucial factor in OPEC’s [Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries] decision to lift the oil embargo in the spring of 1974.

Eager to break the deadlock in the Middle East and sustain détente with the Soviet Union, the Carter administration proposed a peace conference at Geneva, where Washington and Moscow could sit down with their regional friends to press for a comprehensive settlement. Begin, Israel’s newly elected Prime Minister, was dead set against the Geneva Conference, because representatives of the PLO [Palestine Liberation Organization] were likely to be present. Sadat was worried that Carter might strike a deal with Brezhnev to preserve détente which would jeopardise Egypt’s improved relations with the United States. In an unexpected move Sadat flew to Jerusalem in November 1977, where he embraced Begin and announced that Egypt was willing to negotiate a peace treaty with Israel.

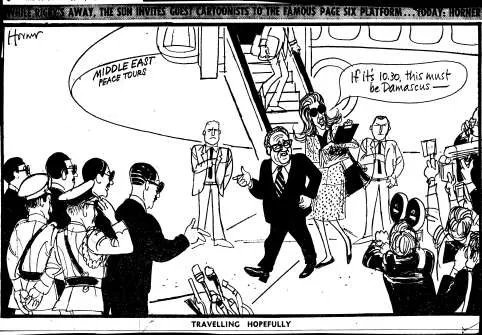

SOURCE B

Cartoon published in the British newspaper The Sun, 23 May 1974, depicting US secretary of state Henry Kissinger on a Middle East tour.

SOURCE C

Timeline of events in the Middle East (1973–1977), from The Longman Companion to the Middle East Since 1914 (second edition), by Ritchie Ovendale, 1998. Ritchie Ovendale was professor of International Politics at the University of Wales, Aberystwyth, UK.

20 October 1973: Henry Kissinger flies to Moscow and together with Brezhnev drafts a ceasefire agreement, which puts a ceasefire in place and calls for the implementation of UN resolution 242 of 1967 after the ceasefire. It also calls for a just and lasting peace. This is accepted by both sides with 22 October as the day for implementation.

5 November 1973: Kissinger starts shuttle diplomacy between Arab countries and Israel following the conclusion of the October War.

18 January 1974: First disengagement agreement signed; it allows limited Egyptian troops on the East Bank of the Suez Canal, a no man’s land supervised by the United Nations in the western parts of Sinai, and limited Israeli forces west of the Giddi and Mitla passes.

31 May 1974: Kissinger manages to convince the Israelis that the Syrian leader Assad is genuine in his assurances that the Golan would not become guerrilla territory. Israel and Syria sign an agreement for separation of forces in the Golan to be supervised and inspected by the United Nations Disengagement and Observer Force.

August 1976: Kissinger concludes a second disengagement agreement between Israel and Egypt, each side moves their forces further from each other.

SOURCE D

Extract from United Nations Security Council Resolution 340, 25 October 1973.

The Security Council,

1. Demands that immediate and complete cease-fire be observed and that the parties return to the positions occupied by them at 4:50pm on 22 October 1973;

2. Requests the Secretary-General, as an immediate step, to increase the number of United Nations military observers on both sides;

3. Decides to set up immediately, under its authority, a United Nations Emergency Force to be composed of personnel drawn from member states of the United Nations except the permanent members of the Security Council and requests the Secretary-General to report on this within 24 hours.

SOURCE E

Extract from a speech by Harold H Saunders, US assistant secretary for Near Eastern Affairs, to the Foreign Affairs Subcommittee of the US Congress, 1975.

The framework for the negotiations that have taken place and the agreements they have produced involving Israel, Syria and Egypt have been provided for by UN Security Council Resolutions 242 and 338.

In accepting the framework, all of the parties have accepted that the objective is peace between them based on mutual recognition, territorial integrity, political independence, the right to live in peace between secure and recognized borders and the resolution of specific issues which comprise the Arab–Israeli conflict.

We have not devised an American solution, nor would it be appropriate for us to do so. This is the responsibility of the parties and the purpose of the negotiating process. But we have not closed our minds to any reasonable solution which can contribute to progress toward our overriding objective in the Middle East – an Arab–Israeli peace. The step-by-step approach to negotiations which we have pursued has been based partly on the understanding that issues in the Arab–Israeli conflict take time to mature.

1. (a) What, according to Source A, were the problems of peacemaking in the Middle East between 1973 and 1978? [3 marks]

(b) What is the message conveyed by Source B? [2 marks]

2. Compare and contrast the views expressed in Sources C and E about the peacemaking process in the Middle East in the 1970s. [6 marks]

3. With reference to their origin and purpose, assess the value and limitations of Source A and Source D for historians studying the peace process in the Middle East. [6 marks]

4. “The US was the driving force in the peace process in the Middle East between 1973 and 1978.” Using the sources and your own knowledge, to what extent do you agree with this statement? [8 marks]

November 2014

These sources and questions relate to the last years of the British Mandate of Palestine (1945–1948).

SOURCE A

Winston Churchill, leader of the Conservative Party, which was at that time the opposition party in the British Parliament, in a speech to the House of Commons (January 1947).

This is a lamentable situation ... it is one of the most unhappy, unpleasant situations into which we have got, even in these troublous [troublesome] years. Here, we are expending hard earned money at an enormous rate in Palestine. Everyone knows what our financial difficulties are – how heavy the weight of taxation. We are spending a vast sum of money on this business. For 18 months we have been pouring out our wealth on this unhappy, unfortunate business. Then there is the manpower of at least 100,000 men in Palestine, who might well be at home strengthening our depleted [weakened] industry. What are they doing there? What good are we getting out of it? We are told that there are a handful of terrorists on one side and 100,000 British troops on the other. How much does it cost? No doubt it is £300 a year per soldier in Palestine. That is £30 million a year. It may be much more – between £30 million and £40 million a year – which is being poured out and which would do much to help to find employment in these islands. One hundred thousand men is a very definite proportion of our Army. How much longer are they to stay there? And stay for what?

SOURCE B

Leslie Illingworth, a political cartoonist, addresses the issue of Britain leaving Palestine in the cartoon “Nurse Gives Notice” from the British satirical magazine, Punch (1948).

SOURCE C

Moshe Dayan, an Israeli military leader and politician, writing in his autobiography, Story of My Life (1976).

On 29 November 1947, when news came through of the United Nations Partition Resolution, I was in Nahalal*. It was night time. I took the children from their beds and we joined the rest of the village in festive dancing in the community hall ... I felt in my bones the victory of Judaism, which for two thousand years of exile from the Land of Israel had withstood persecutions, the Spanish Inquisition, pogroms, anti-Jewish decrees, restrictions and the mass slaughter by the Nazis in our own generation ... We were happy that night and we danced, and our hearts went out to every nation whose United Nations representative had voted in favour of the resolution.

* Nahalal: Jewish settlement in what was still Palestine in 1947

SOURCE D

Noah Lucas, a professor of History and a Jewish supporter of Zionism, writing in an academic book, The Modern History of Israel (1975).

Arab and Zionist diplomacy now concentrated on the United Nations as the General Assembly prepared to meet in mid-September 1947 to decide Palestine’s future ... Zionist political pressure within America in conjunction with Soviet determination to hasten the collapse of the British position in the Middle East brought a momentary coming together of US and Russian policy in support of the partition of Palestine. Diplomatic competition between the Zionist and the Arab supporters concentrated on persuading the representatives of the small powers, especially those of Latin America. In view of the dependence of many of these upon the United States the advantage lay with the Zionists ... Therefore, when the issue was brought to the vote in the United Nations Assembly on 29 November 1947 the Zionists secured the necessary two-thirds majority in favour of partition ...

There is no denying the importance of this United Nations decision as a factor in the creation of Israel as an independent state, nor the importance of Zionist diplomacy in achieving this decision.

SOURCE E

Mark Tessler, a professor of Political Science, writing in an academic history book, A History of the Israeli–Palestinian Conflict (1994).

[The Arabs believed] that Palestine was an integral part of the Arab world and that from the beginning its indigenous [local] inhabitants had opposed the creation in their country of a Jewish national home. They also insisted that the United Nations, a body created and controlled by the United States and Europe, had no right to grant the Zionists any portion of their territory. In what was to become a familiar Arab charge they insisted that the Western world was seeking to salve [soothe] its conscience for the atrocities of war and was paying its own debt to the Jewish people with someone else’s land.

1. (a) What, according to Source A, is the opinion expressed by Winston Churchill about Britain’s presence in Palestine? [3 marks]

(b) What is the message conveyed by Source B? [2 marks]

2. Compare and contrast the views expressed in Sources C and E about the UN General Assembly’s approval, in November 1947, of the partition of Palestine into two states. [6 marks]

3. With reference to their origin and purpose, assess the value and limitations of Source A and Source D for historians studying the factors that led to the establishment of the state of Israel. [6 marks]

4. Using the sources and your own knowledge, to what extent do you agree that Britain’s financial and economic weakness after the Second World War was the main reason for the establishment of the state of Israel in 1948? [8 marks]