At the Giza pyramid complex on the outskirts of Cairo, showing the three

Great Pyramids. Also at the site is the massive Great Sphinx, several

cemeteries, a workers' village and an industrial complex located roughly five miles into the desert from the old town of Giza on

the Nile, some fifteen miles southwest of Cairo city centre. The pyramids,

which have historically served as emblems of ancient Egypt in the

Western imagination, were popularised in Hellenistic times when the

Great Pyramid was listed by Antipater of Sidon as one of the Seven

Wonders of the World. It is by far the oldest of the ancient Wonders and

the only one still in existence.

At the Giza pyramid complex on the outskirts of Cairo, showing the three

Great Pyramids. Also at the site is the massive Great Sphinx, several

cemeteries, a workers' village and an industrial complex located roughly five miles into the desert from the old town of Giza on

the Nile, some fifteen miles southwest of Cairo city centre. The pyramids,

which have historically served as emblems of ancient Egypt in the

Western imagination, were popularised in Hellenistic times when the

Great Pyramid was listed by Antipater of Sidon as one of the Seven

Wonders of the World. It is by far the oldest of the ancient Wonders and

the only one still in existence.

The pyramids have provoked some of the most far-fetched of all human speculation. They are visible from space, and the notion has sprung up that visitors from outside the solar system built them. Elaborate calculations have been produced to show that the three largest at Giza form a pattern matching stars in Orion’s belt as they appeared in 2600 BC, though how such a simple figure, delayed through the reigns of at least four pharaohs, could have given any satisfaction to anyone along the way or justified the expenditure by those who would see only the first or second dot of three is hard to see. Undeniably, these three are aligned on the cardinal points with surprising accuracy, and the levelling of the sloping ground and regularity of the construction show remarkable control. So we jump from such evidence of technical skill to the idea that the overall configuration must mean something. But the three were not always three, and even now the idea that they form a group is our perception anyway.

Robert Harbison (20-21) Travels in the History of Architecture

In front of the oldest pyramid in Giza and the largest in Egypt, the Great Pyramid of Khufu, standing 146 metres high when it was completed around 2570 BCE. After 46 windy centuries, its height has been reduced by nine metres. About 2.3 million limestone blocks, thought to weigh about 2.5 tonnes each, were used in the construction. On the right is the mastaba of Seshemnufer IV is in front of the entrance to the second largest pyramid, that of Khafre.

Evolution of the mastaba of the Thinite period , the pyramids were initially exclusively royal tombs. Later, some were built for other people of the royal family. Khufu seems to have been the first to authorize his wives to have such a tomb built. There are one hundred and eighteen pyramids in Egypt, varying greatly in their date of construction, size and configuration. The largest and most iconic, the Pyramid of Cheops , is one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World and is a World Heritage Site . Summary From Mastabas to Pyramids Step Pyramid of Djoser . The mastaba , a quasi-rectangular construction, was the burial place of the sovereigns of the Old Kingdom . The reasons for the transition from mastabas to pyramids are not clearly established, but it is generally mentioned the desire to reach increasingly considerable heights to demonstrate the importance and power of the deceased pharaoh . The first mastabas, with a single floor, first evolved into two-story mastabas to accommodate new funerary structures, the second floor being narrower and lower than the first. At the beginning of the Third Dynasty (around -2700 to -2600), the mastabas became so-called step pyramids , made up of several successive floors. The first and most famous of these step pyramids is the Pyramid of Djoser at Saqqara , whose architect was Imhotep . Imhotep wanted to build a stepped pyramid rising like a gigantic staircase towards the sky in order to symbolize the ascension of the deceased from the "underworld" to the "Heavens". Rhomboidal pyramid . Smooth-sided pyramids of Giza . The next step in the evolution of the step pyramids was the construction by King Snefru of a "bent pyramid" at the site of Dahshur . The bent pyramid is an intermediate stage between the step pyramid and the smooth-sided pyramid. The bent pyramid is a pyramid whose smooth faces form a slope with decreasing inclination sections towards the summit. The non-uniformity of this slope could be explained by architectural difficulties and by the instability of the masonry of the pyramid. This type of pyramid is the last step leading to the ultimate stage of the evolution of the pyramids of Egypt towards the smooth -sided pyramids of the 4th dynasty (c. -2573 to -2454). Among the most famous are the pyramids of the pharaohs Khufu , Khafre and Mykerinos at Giza near Cairo . These pyramids are followed by the pyramids with texts of the 5th and 6th dynasties , smaller and more fragile, today in a poor state of preservation, then the brick pyramids of the 12th dynasty . Despite a stone facing, these pyramids are generally in ruins due to the fragility of the brick and the abandonment of the macrostructure model with core and accretions 1 . Finally , the pharaohs of the 25th dynasty had Nubian pyramids built in both brick and stone. So there are four major shapes of pyramids: the step pyramid : a pyramid in the form of a staircase, originally a superposition of mastabas with different bases. For example, the pyramid of Djoser has six steps for a height of 60 meters and a base of 109 × 121 meters. The masonry slices, inclined at 16° to the vertical, are 2.60 meters high; the rhomboidal pyramid : pyramid with two inclined planes, one starting from the bottom to the middle of the building (58° slope), the other going towards the tip (43° 22'). This break in slope would be due to a change of plane occurring during construction 2 ; the smooth-sided pyramid : a pyramid with four straight walls, covered with very fine limestone giving them a smooth appearance. The pyramid of Cheops reached 146 meters in height (currently 138 meters) for a base of 230 meters and a slope of 51° 50'. That of Chephren has a slope of 53° for a height of 143.50 meters and a base of 215 meters. As for that of Mykerinos , it measured 66 meters in height for a base of 105 meters and a slope of 51° 20'; the sarcophagus-shaped pyramid: despite certain inscriptions designating them as pyramids, these mausoleums are not pyramids from a strictly geometric point of view. Within the funeral complex Main article: Egyptian pyramid complex . Funerary complex of Djoser . With the predynastic period and then the Thinite period, we witness a characteristic evolution of the funerary customs of the ancient Egyptians which translate for the most powerful personage of the kingdom by the digging of impressive underground galleries accessing the royal vault and the construction of monumental constructions in raw bricks marking in the Abydenian desert the final resting place of the king who became god. These structures became more and more complex both by their internal and external arrangements during the 2nd and 3rd dynasties . The pharaohs of these first lineages will further develop this architecture and the principles which presided over it by having large enclosures built intended to serve the funerary cult of the king who remained buried apart in his cenotaph below a monument reminiscent of the benben , the primordial mound or more probably the tomb of Osiris . It was with Djoser of the Third Dynasty that the architecture of royal tombs took on a new impetus, uniting these two previously distinct elements in a single complex and giving the funerary monument an unequalled scale. Not only was the architecture made of stone, which represented a true technical revolution, but the pyramidal form was born, reflecting the future of Pharaoh once he had joined the abode of the gods, an indication of a theological revolution. Indeed, this chosen form would very quickly become the main element of the funerary complex to the point that it qualified its destination and that it would henceforth be a pyramidal complex . Throughout this Old Kingdom, it appears certain in view of the discoveries of the pyramid texts that this architecture responded to precise codes, skillfully thought out and then inscribed in the very stone of the funerary vaults in order to add the eternal writing to this stone setting intended to ensure the immortality of a divine king. Construction Main article: Theories on the method of construction of the Egyptian pyramids . Different types of external construction ramp assumptions. The pyramids demonstrate, for their time, the great knowledge of Egyptian engineers capable of building such monuments with very rudimentary means. The methods of construction of the Egyptian pyramids remain uncertain. The documentary and archaeological data on these gigantic construction sites remain very fragmentary, while theories flourish and multiply, especially since the end of the 19th century . Hundreds of works devoted to the pyramid of Cheops claim to have finally succeeded in unraveling the mystery surrounding its construction. Theories generally focus on the Great Pyramid, starting from the principle that a method that can explain its construction can also be applied to all the other pyramids of Egypt. In fact, there is no evidence that the same methods were applied to all the pyramids, of all types, all sizes and all periods. Mysteries and fantasy Main article: Pyramidology . Pyramid of Khafre . Throughout history, these gigantic stone constructions have excited the imagination. The main reason is perhaps that rarely in the history of humanity will the elements that allowed their construction come together again: an all-powerful theocratic power , a rich and prosperous country, a large workforce, a highly developed administration and great empirical knowledge. Under these conditions, it is more rewarding for the civilizations that will contemplate these "wonders" to attribute an extraordinary origin to them than to admit their own limits. The nascent Egyptology of the 19th century raised more questions than it could answer, and modern myths quickly filled the gaps it had left. It would take Egyptologists many years to try to dispel these myths, which, despite everything, are still very much alive in contemporary culture. What remains of "mysteries" are in fact only questions that do not yet have unanimous answers. We can cite: the existence or not of hidden chambers in the pyramid of Cheops (with the "treasures" that they could contain), the exact protocol for the construction of the pyramids (if it was unique), the exact period of construction, or even the symbolism that these monuments had in the eyes of their builders. Astronomical rapprochement Main articles: Orion correlation theory and Mathematical observation of the Great Pyramid of Khufu . Some Egyptologists (like Selim Hassan ) or archaeo-astronomers (like Robert Bauval) propose a theory according to which there exists a correlation between the position and orientation of the pyramids of Giza and the position of the stars and in particular of the constellation of Orion . Pyramid of Cheops Pyramid of Cheops . The Great Pyramid of Khufu is undoubtedly the most famous pyramid. Forming a square pyramid 137 m high (originally 146 m , i.e. higher than St. Peter's Basilica in Rome (139 m )), it was built more than 4,500 years ago, under the 4th Dynasty , in the center of a vast funerary complex located in Giza . It is the only one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World to have survived. For thousands of years, it was the human construction of all records, the tallest, the most voluminous and the most massive. A true symbol of an entire country, this monument has been scrutinized and studied tirelessly for more than 4,500 years. The tomb, a true masterpiece of the Old Kingdom , represents the concentration and culmination of all the architectural techniques developed since the creation of monumental stone architecture by Imhotep for the pyramid of his sovereign Djoser . However, the many architectural particularities and the feats achieved make it a pyramid apart that never ceases to captivate the imagination. The largest pyramids in Egypt The ranking below uses the length of the base of the pyramid as a reference (the height is given for information purposes only): Pyramid of Cheops ( 4th Dynasty ) : 230 m (146 m ); Red pyramid , Snefrou ( 4th dynasty ) : 219 m (105 m ); Pyramid of Khafre ( 4th dynasty ) : 215 m (143 m ); Bent Pyramid , Snefru ( 4th Dynasty ) : 189 m (105 m ); Pyramid of Meïdoum , Snefrou ( 4th dynasty ) : 144 m (94 m ); Pyramid of Djoser ( 3rd dynasty ): 121 × 109 m ( 62 m ). Chronological order See the attached article: Location of the Egyptian pyramids . Picture Pyramid and subsidiary pyramids Dynasty Pharaoh Location Base dimensions Original height Current height Tilt of faces Remarks Old Kingdom Pyramid of Djoser 3rd dyn . Djoser Saqqara 109.0 m × 121.0 m 62.0 m - Step Pyramid Sekhemkhet Pyramid 3rd dyn . Sekhemkhet Saqqara 120.0 m (~70.0 m) 8.0 m - Unfinished Step Pyramid Sliced pyramid 3rd dyn . Khaba Zaouiet el-Aryan 84.0 m (~40.0 m) - Unfinished Step Pyramid Pyramid number 1 of Lepsius 3rd dyn . ? Houni ? Abu Rawash 215.0 m ? (105.0 m - 150.0 m) ? ~20.0 m - Undefined superstructure (pyramid or mastaba) Pyramid of Athribis 3rd / 4th dyn . ? Houni ? / Snefru ? Athribis ~20.0 m unknown - Small pyramid that has disappeared and whose function and attribution are controversial. The only pyramid in the delta and, until the 20th century , the northernmost of the pyramids in Egypt. Pyramid of Elephantine 3rd / 4th dyn . ? Houni ? / Snefru ? Elephantine 18.5 m 10.5 m - 12.5 m 5.1 m - Provincial pyramid Pyramid of Edfu 3rd / 4th dyn . ? Houni ? / Snefru ? Edfu 18.8 m 5.5 m - Provincial pyramid Al-Koula Pyramid 3rd / 4th dyn . ? Houni ? / Snefru ? near Hierakonpolis 18.6 m 8.25 m - Provincial pyramid Pyramid of Nagada 3rd / 4th dyn . ? Houni ? / Snefru ? near Nagada 18.4 m 14.0 m 4.5 m - Provincial pyramid Pyramid of Sinki 3rd / 4th dyn . ? Houni ? / Snefru ? in Abydos 18.5 m 12.5 m 1.35 m - Provincial pyramid Pyramid of Zaouiet el-Meïtin 3rd / 4th dyn . ? Houni ? / Snefru ? near Al-Minya 22.5 m ~17.0 m 4.8 m - Provincial pyramid Pyramid of Seilah 4th dyn . Snefru Seilah ~25.0 m 6.80 m - Provincial pyramid Pyramid of Meidum 3rd / 4th dyn . Huni and Snefru Meidoum 144.3 m 91.9 m 51°50′ The first attempt at a smooth-sided pyramid Pyramid of worship 26.3 m ? - Step pyramid. First satellite pyramid Rhomboidal pyramid 4th dyn . Snefru Dahshur 189.4 m 104.7 m 101.1 m 54° / 43° The only one with a change in slope, and the best preserved Pyramid of worship 52.5 m 25.75 m 43° Red Pyramid 4th dyn . Snefru Dahshur 219.1 m 109.5 m 43°22' The first pyramid with smooth faces Pyramid of Cheops 4th dyn . Cheops Giza 230.3 m 146.6 m 138.7 m 51°50′ The largest pyramid in Egypt Pyramid G1D 21.75 m 13.8 m 51°50′ Pyramid of the Ka cult Pyramid G1A ~47.5 m ~30.1 m 51°50′ Pyramid attributed by some Egyptologists to Queen Heteph- Heres I Pyramid G1B ( Merits I re ) ~48.0 m ~30.5 m 51°50′ Pyramid G1C ( Hénoutsen ) ~44.0 m ~28.0 m 51°50′ Pyramid of Djedefre 4th dyn . Djedefre Abu Rawash 106.2 m (57.0 m – 67.0 m) 11.4 m 51°50′ The northernmost Pyramid of worship 26 m? ? ? Queen's Pyramid 10.5 m 11.8 m 66°2′ Pyramid of Khafre 4th dyn . Khafre Giza 215.2 m 143.5 m 53°7′ has kept much of its coating Worship Pyramid (G2a) 21.0 m 15 m 53°7′ Large excavation 4th dyn . Baka ? Zaouiet el-Aryan ~200.0 m - Unfinished Pyramid Pyramid of Mykerinos 4th dyn . Mykerinos Giza 102.2 m × 104.6 m 65.6 m 62.0 m 51°20′ Pyramid G III -a 44.1 m 28.4 m 52°7′ Pyramid G III -b 31.2 m 21.0 m - Step Pyramid Pyramid G III -c 31.6 m 21.0 m - Step Pyramid Mastaba el-Faraoun 4th dyn . Shepseskaf South Saqqara 99.6 m × 74.4 m 18.9 m - A tomb in the form of a sarcophagus whose infrastructure would inspire that of the following pyramids Pyramid of Khentkaous I 4th dyn . Khentkaous I re Giza 45.8 m × 45.5 m 17 m - A two-story, stepped pyramid Pyramid number 50 of Lepsius 4th / 5th dyn . ? ? Dahshur Pyramid of Userkaf 5th dyn . Userkaf Saqqara 73.3 m 49.4 m 53°7′ Pyramid of worship 21.0 m 13.9 m 53°7′ Pyramid of Neferhetepes 26.2 m 16.8 m 52°7′ First pyramid complex for a queen Pyramid of Sahure 5th dyn . Sahoure Abusir 78.8 m 47.3 m 36.0 m 50°11′ Pyramid of worship 15.8 m 11.6 m 56°18′ Pyramid of Neferirkare 5th dyn . Neferirkare Abusir 105.0 m 72.0 m 44.5 m 54° Pyramid of Khentkaous II 5th dyn . Khentkaous II Abusir 25.0 m 16.2 m 4.0 m 52°7′ Pyramid of worship 5.2 m ~4.5 m 60° Pyramid of Neferefre 5th dyn . Neferefre Abusir ~65.0 m Pyramid of Nyuserre 5th dyn . Nyuserre Abusir 78.9 m 50.0 m 51°50′ Pyramid of worship 15.8 m ~10.5 m 56°18′ Pyramid number 24 of Lepsius 5th dyn . Nyuserre ? Abusir 31.5 m? 27.3 m? 60°15′ Pyramid of worship ~10.0 m ? ? Pyramid number 25 of Lepsius I 5th dyn . Nyuserre ? Abusir 27.70 m × 21.53 m ? Pyramid number 25 of Lepsius II 21.70 m × 15.70 m ? Pyramid of Menkaure 5th dyn . Menkaouhor Saqqara 52.0 m Unfinished Pyramid 5th dyn . Chepseskare ? Abusir (~105.0 m) ? Pyramid of Djedkare Isesi 5th dyn . Djedkare Saqqara South 78.8 m 52.5 m 51°50′ It will serve as a model for the following pyramids. Pyramid of worship 15.8 m 17.1 m ? 65°13′ Queen's Pyramid 41.0 m 21.0 m 62° Pyramid of worship 4.0 m Pyramid of Ounas 5th dyn . Ounas Saqqara 57.7 m 43.0 m 56°18′ The first pyramid of texts Pyramid of worship 11.5 m 11.5 m 63°26′ Pyramid of Teti 6th dyn . Teti Saqqara 78.8 m 52.0 m 53°7′ Pyramid of worship 15.7 m 15.7 m 63°26′ Pyramid of Iput I 21.0 m 21.0 m 7.0 m 63° Pyramid of Khouit II 21.0 m ? ? Sescheschet Pyramid 22.0 m ~14.0 m ~5.0 m 51° Pyramid of Pepi I 6th dyn . Pepi I Saqqara 78.8 m 52.5 m 12.0 m 53°7′ Pyramid of texts Pyramid of worship 15.7 m 15.7 m 63°26′ Pyramid of Noubounet 21.0 m 21.0 m Pyramid of Inenek Inti / Inti 21.0 m 21.0 m 63°26′ Pyramid of worship 6.3 m 6.3 m 63° West Pyramid 21.0 m 21.0 m 3.0 m Pyramid of Meretites II 21.0 m ? ? Pyramid of Ankheseenpepi II 31.2 m ? ? Pyramid of texts Pyramid of Ankheseenpepi II 15.8 m ? ? Pyramid of worship 3.1 m 3.1 m 63° Pyramid of Haaherou 22.6 m ? ? Pyramid of Behenou Pyramid of worship Pyramid of Merenre I 6th dyn . Merenre I Saqqara 78.6 m (52.4) m 53°7′ Pyramid of texts Pyramid of worship 15.7 m? 15.7 m? 63°26′ Pyramid of Pepi II 6th dyn . Pepi II Saqqara 78.8 m 52.5 m 53°7′ Pyramid of texts Pyramid of worship 15.7 m 15.7 m 63°26′ Pyramid of Neith 23.9 m 21.5 m 60°56′ Pyramid of texts Pyramid of worship 5.2 m 4.7 m 61° Pyramid of Iput II 22.0 m 15.8 m 55° Pyramid of worship 3.7 – 4.2 m ? ? 63°? Pyramid of Oudjebten 23.9 m 25.6 m 65°13′ Pyramid of texts Pyramid of worship ? ? ? First Intermediate Period Pyramid of Iti 8th dyn . Iti ? Pyramid of Neferkare 8th dyn . Neferkare Nebi ? Pyramid of Qakarê-Ibi 8th dyn . Qakare Ibi Saqqara 31.5 m 21.0 m 3.0 m 53°7′ ? Pyramid of texts Pyramid of Khoui 8th dyn . Khoui Dara 130.0 m 4.0 m Step pyramid or mastaba? Pyramid of Merikare II 10th dyn . Merikare II Saqqara Middle Kingdom Pyramid of Rêhérychefnakht 11th / 12th dyn . Rêhérychefnakht Saqqara 13.1 m Reuse pyramid in the Pepi I complex Pyramid of Amenemhat I 12th dyn . Amenemhat I Light 84.0 m 55.0 m 54°27′ Pyramid of Sesostris I 12th dyn . Sesostris I Light 105.0 m 61.3 m 49°23′ Pyramid of worship 15.8 m / 18.4 m 15.8 m / 18.4 m 63° Pyramid of Neferu 21.0 m 18.9 m 63°26′ Itakaiet Pyramid 16.8 m 16.8 m 63°26′ Queen's Pyramid No. 3 16.8 m 16.8 m 63°26′ Queen's Pyramid No. 4 16.8 m ? ? Queen's Pyramid No. 5 16.3 m 16.3 m 63°26′ Queen's Pyramid No. 6 15.8 m 15.8 m ? 63°26′ ? Queen's Pyramid No. 7 15.8 m 15.8 m ? 63°26′ ? Queen's Pyramid No. 8 15.8 m 15.8 m ? 63°26′ ? Queen's Pyramid No. 9 15.8 m 15.8 m ? 63°26′ ? Pyramid of Amenemhat II ( white pyramid ) 12th dyn . Amenemhat II Dahshur 84.0 m ? ? Pyramid of Sesostris II 12th dyn . Sesostris II El-Lahoun 106.0 m 48.7 m 42°33′ Queen's Pyramid 26.6 m 18.8 m? 54°27′ ? Pyramid of Sesostris III 12th dyn . Sesostris III Dahshur ~105.0 m ~63.0 m ? 50°11′ Pyramid of Nysou-Montjou ( no . 1) 16.8 m ? ? Pyramid of Queen Nefret-Henout ( n o 2) 16.8 m 14.7 m / 16.8 m 60°15′/ 63°26′ ? Pyramid of Queen Itakayet ( No. 3 ) 16.8 m 14.7 m / 16.8 m 60°15′/ 63°26′ ? Queen's Pyramid ( No. 4 ) 16.8 m 13.1 m ? 57°15′ Pyramid of the Ka cult ( n o 5) Pyramid of Oueret I ( no . 6 ) 22.1 m 19.3 m/ 22.1 m ? 60°15′ ?/ ? Pyramid of Oueret II ( no . 7) 22.1 m 19.3 m? 60°15′ ? Pyramid of Amenemhat III 12th dyn . Amenemhat III Dahshur 105.0 m 75.0 m 55°? Hawara Pyramid 12th dyn . Amenemhat III Hawara 105.0 m ~58.0 m 48°48′ Site of the famous labyrinth described by the ancient Greeks Pyramid of Neferuptah 12th dyn . Neferuptah Hawara ~45.0 m ~30.0 m ~53° Dahshur Pyramid Center 12th / 13th dyn . Amenemhat II ? / Amenemhat IV ? Dahshur - Southern Pyramid of Mazghouna 12th / 13th dyn . Amenemhat IV ? Mazghouna 52.5 m North Pyramid of Mazghouna 12th / 13th dyn . Neferusobek ? Mazghouna > 52.5 m Second Intermediate Period Pyramid of Ameni Kemaou 13th dyn . Ameni Kemaou Dahshur 52.5 m ? ? Pyramid of Khendjer 13th dyn . Khendjer Saqqara 52.5 m 37.5 m 1.0 m 55° Pyramid of worship (or queen?) 25.5 m ? ? Unfinished Pyramid of South Saqqara 13th dyn . ? Saqqara South 94.5 m SAK S3 Pyramid 13th dyn . ? Saqqara South 55.0 m SAK S7 Pyramid 13th dyn . ? Saqqara South Pyramid A of Dahshur South 13th dyn . ? Dahshur Pyramid B of Dahshur South 13th dyn . ? Dahshur DAS 46 Pyramid 13th dyn . ? Dahshur DAS 49 Pyramid 13th dyn . ? Dahshur DAS 50 Pyramid 13th dyn . ? Dahshur DAS 51 Pyramid 13th dyn . ? Dahshur DAS 53 Pyramid 13th dyn . ? Dahshur Pyramid of Aja I 13th dyn . Aja I unknown Pyramid of Sobekemsaf I 17th dyn . Sobekemsaf I Dra Abou el-Naga Pyramid of Sobekemsaf II 17th dyn . Sobekemsaf II Dra Abou el-Naga Pyramid of Antef VI 17th dyn . Antef VI Dra Abou el-Naga 60° Pyramid of Antef V 17th dyn . Antef V Dra Abou el-Naga 11.0 m 13.0 m 1.20 m Pyramid of Kamose 17th dyn . Kamose Dra Abou el-Naga 8.0 m 66° New Empire Pyramid of Ahmose 18th dyn . Ahmose I Abydos 52.5 m 60° It is actually a cenotaph Some pyramids suffering from a very advanced state of disrepair still escape classification: Pyramid number 1 of Lepsius (located in Abu Rawash ) Pyramid number 24 of Lepsius (located in Abusir ) Pyramid number 25 of Lepsius (located in Abusir ) Pyramid number 29 of Lepsius (located in Saqqara and recently attributed to Menkaure ) Pyramid number 50 of Lepsius (located in Dahshur ) Lost Pyramids One hundred and twenty-three pyramids (including subsidiary and provincial pyramids) are currently known . 4 The pyramids of several Old Kingdom rulers have not yet been located, including those of Userkare , Merenre II , and Nitocris . Similarly, pyramids of queens still lie buried beneath the sand, such as that of Ankheseenpepi I , for example, to which must probably be added a few pyramids of obscure rulers and queens from the First Intermediate Period and the Second Intermediate Period who have left no trace in history. German Egyptologist Rainer Stadelmann has discovered the remains of three pyramids, all located in Dahshur , Pyramid A of South Dahshur , Pyramid B of South Dahshur and the anonymous pyramid of Dahshur . The latter, located south of the pyramid of Amenemhat II , was unfortunately badly damaged by the construction of a pipeline . The two pyramids of South Dahshur have not yet been studied. A study was carried out in 2006 by the German team of the Deutsches Archäologisches Institut . It aimed to locate remains in two areas untouched by any prospecting, those of South Saqqara and South Dahshur (near Mazghouna ). It emerged that, in addition to many diverse monuments, unfinished pyramids must rest under the sands. The team named two pyramids, pyramid SAK S3 and pyramid SAK S7 , located near the unfinished pyramid of South Saqqara and the pyramid of Khendjer , as well as pyramid DAS 53 , near the northern pyramid of Mazghouna . No excavation is currently planned to uncover either of these monuments. In 2013, a Belgian team discovered the Khay pyramid in Luxor 5 . Texts Main article: Pyramid Texts . "You will not die out, you will not end. Your name will last among men. Your name will come to be among the gods." This promise of eternal life addressed to Pepi I and engraved on the walls of his funerary apartment belongs to one of the oldest collections of texts in humanity. It is likely that these incantations, which helped the sovereign to be reborn in the afterlife, were recited by the priests until the 5th dynasty . If some hieroglyphs decorated the funerary monuments of Djoser , it is from Unas , the last king of the 5th dynasty , that the pyramid texts were engraved in the royal funerary apartments. By having them engraved on the walls of their tomb, the kings appropriated them and above all freed themselves from the influence of the ecclesiastics . The texts also included formulas which assured the deceased the strength necessary for his final journey. Magic formulas were supposed to protect the tomb against external intrusions. Arranged in long columns, the text is traced using malachite powder , which gives it a green tint, a symbol of rebirth like the young shoots that stand on the silt after the floods of the Nile . But at the end of the Old Kingdom , the royal pyramids lost exclusivity and from the First Intermediate Period , individuals appropriated fragments of the text that they had inscribed inside their sarcophagi. These texts from the sarcophagi are partly included in the Book of the Dead . Inscribed on papyrus , the text will then be placed in the tomb of the deceased throughout the Late Period .

Climbing up

Entering the tomb within the pyramid of Henutsen

Dubbed the Sphinx by the ancient Greeks because it resembled the mythical winged monster with a woman’s head and lion’s body who set riddles and killed anyone unable to answer them, it was carved from the bedrock at the bottom of the causeway to the Pyramid of Khafre; geological survey has shown that it was most likely carved during this pharaoh’s reign, so it probably portrays his features, framed by the nemes (the striped headcloth worn only by royalty). It can be seen in the GIF that the nemes has been buttressed since the war. As is clear from the accounts of early Arab travellers, the nose was hammered off sometime between the 11th and 15th centuries; examination of the Sphinx's face shows that long rods or chisels

were hammered into the nose area, one down from the bridge and another

beneath the nostril, then used to pry the nose off towards the south,

resulting in the one-metre wide nose being lost. Mark Lehner, who

performed an archaeological study, concluded that it was intentionally

broken with instruments at an unknown time between the 3rd and 10th

centuries, although Napoleon and his Frenchmen are also greatly responsible. Part of the fallen beard was carted off by 19th-century adventurers and is now safely on display in the British Museum. These days the Sphinx has potentially greater problems: the monument is suffering the stone equivalent of cancer and is being eaten away from the inside; pollution and rising groundwater are the likeliest causes. A succession of restoration attempts unfortunately sped up the decay rather than halting it. The Sphinx’s shiny white paws are the result of the most recent effort.

Reconstruction of how the sphinx might originally have appeared. The face, although better preserved than most of the statue, has been battered by centuries of weathering and vandalism. In 1402, an Arab historian reported that a Sufi zealot had disfigured it “to remedy some religious errors.” That said, there are still some clues to what the face looked like in its prime. Archaeological excavations in the early 19th century found pieces of its carved stone beard and a royal cobra emblem from its headdress. Residues of red pigment are still visible on the face, leading researchers to conclude that at some point, the Sphinx’s entire visage was painted red. Such residues of red pigment visible on areas of the Sphinx's face and traces of yellow and blue pigment have also been found elsewhere on the Sphinx, leading Mark Lehner to suggest that the monument "was once decked out in gaudy comic book colours". However, as with the case of many ancient monuments, the pigments and colours have since deteriorated, resulting in the yellow/beige appearance it has today.

At

the Aswan Dam with the so-called monument of Arab-Soviet Friendship

(Lotus Flower) in the background, designed by architects Piotr Pavlov,

Juri Omeltchenko and sculptor Nikolay Vechkanov.

There

will not be many takers these days for the Nile cruise-ships, but if

you are there, ponder on the Aswan Dam. Not the vast and ugly

Soviet-built one, but a smaller, elegant one, built by the British in

1898. The consul-general (meaning imperial governor: one of the British

strengths is the under-stated title) Lord Cromer could take much pride

in it. It was an engineering triumph, a symbol of the transformation

that the British had worked in a quarter-century in Egypt: planned

towns, drains, ordered finance, justice for the peasant. Germans (their

archaeologists were spies) were hugely envious. In the first world war,

they were busy fomenting a holy war to drive the British out — the idea

was to inspire an Islamist insurgency, to destabilise the British. This

is the plotline of John Buchan’s novel Greenmantle, and of Sean

McMeekin’s recent book about the Berlin-Baghdad railway — seen, then, as

an artery along which the blood of a new and mighty German empire would

flow.

Philae

Philae is currently an island in the reservoir of the Aswan Low Dam,

downstream of the Aswan Dam and Lake Nasser, Egypt. Philae was

originally located near the expansive First Cataract of the Nile River

in southern Egypt, and was the site of an Ancient Egyptian temple

complex. These rapids and the surrounding area have been variously

flooded since the initial construction of the Old Aswan Dam in 1902.

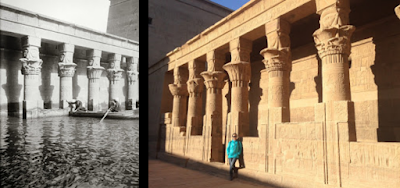

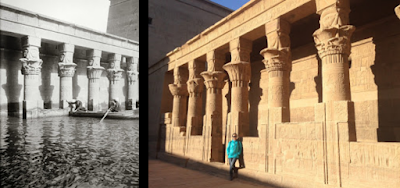

The site at the turn of the century, showing its dilapidated state and proneness to flooding after the Aswan Low Dam was completed on the Nile River by the British in 1902 which threatened to submerge many ancient landmarks, including the temple complex of Philae. The height of the dam was raised twice, from 1907–1912 and from 1929–1934, and the island of Philae was nearly always flooded. In fact, the only times that the complex was not underwater was when the dam's sluices were open from July to October. It was proposed that the temples be relocated, piece by piece, to nearby islands, such as Bigeh or Elephantine. However, the temples' foundations and other architectural supporting structures were strengthened instead. Although the buildings were physically secure, the island's attractive vegetation and the colors of the temples' reliefs were washed away. Also, the bricks of the Philae temples soon became encrusted with silt and other debris carried by the Nile. The

temple complex was later dismantled and relocated to nearby Agilkia

Island as part of the UNESCO Nubia Campaign project, protecting this and

other complexes before the 1970 completion of the Aswan High Dam.

At

the end is the entrance of the Temple of Isis, marked by the 18m-high

towers with reliefs of Ptolemy XII Neos Dionysos smiting enemies as he

holds one on either tower by the hair whilst holding his mace high above

his head. He is accompanied by Isis, Horus of Edfu and Hathor. There

are two smaller scenes above this depiction; on the left the pharaoh

offers the crown of Upper and Lower Egypt to Horus of Edfu and Nephthys;

and on the right he offers incense to Isis and Horus the child. The

pharaoh is also depicted "smiting" his enemies on the western tower in

the presence of Isis, Horus of Edfu and Hathor. Above this scene the

pharaoh appears with Unnefer (a form of Osiris) and Isis and also with

Isis and Horus the child. These decorations were badly damaged by early

Coptic Christians and later the French during their invasion of 1799. At

the base of the first pylon a series of small personified Nile figures

present offerings. Strabo refers to this building in xvii.1, 28 when he

describes "two walls of the same height as those of the

temple, which are prolonged in front of the pronaos."

At

the end is the entrance of the Temple of Isis, marked by the 18m-high

towers with reliefs of Ptolemy XII Neos Dionysos smiting enemies as he

holds one on either tower by the hair whilst holding his mace high above

his head. He is accompanied by Isis, Horus of Edfu and Hathor. There

are two smaller scenes above this depiction; on the left the pharaoh

offers the crown of Upper and Lower Egypt to Horus of Edfu and Nephthys;

and on the right he offers incense to Isis and Horus the child. The

pharaoh is also depicted "smiting" his enemies on the western tower in

the presence of Isis, Horus of Edfu and Hathor. Above this scene the

pharaoh appears with Unnefer (a form of Osiris) and Isis and also with

Isis and Horus the child. These decorations were badly damaged by early

Coptic Christians and later the French during their invasion of 1799. At

the base of the first pylon a series of small personified Nile figures

present offerings. Strabo refers to this building in xvii.1, 28 when he

describes "two walls of the same height as those of the

temple, which are prolonged in front of the pronaos."

The

Mammisi (birth house), surrounded on three sides by a colonnade of

floral topped columns each crowned with a sistrum and Hathor-headed

capital. The walls flanking the columns depict the pharaohs Ptolemy VI,

VIII and X and the Roman Emperor Tiberius along with a number of gods. Dating from around 300 BCE, it was the first Ptolemaic birth house erected beside the temple of Isis on the island of Philae during the reign of Ptolemy II Philadelphus and Ptolemy III Euergetes and was dedicated to the young Horus. Unlike other mammisis, it was situated in a courtyard between the first and the second pylon on the parallel axis to the main temple, possibly because of the very limited space on the island.

At

the Grand Portico of the Temple of Philae and as depicted by David

Roberts in 1848. English novelist, journalist, traveller and

Egyptologist Amelia Edwards described it as "a place in which time seems

to have stood as still as in that immortal palace where everything went

to sleep for a hundred years. The bas-reliefs on the walls, the

intricate paintings on the ceilings, the colours upon the capitals are

incredibly fresh and perfect. These exquisite capitals have long been

the wonder and delight of travellers in Egypt. They are all studied from

natural forms - from the lotus in bud and blossom, the papyrus, and the

palm. Conventionalised with consummate skill, they are at the same time

so justly proportioned to the height and girth of the columns as to

give an air of wonderful lightness to the whole structure." Today

only ten columns remain. On the east side the reliefs were replaced by

Coptic Christian crosses where altars to the Virgin Mary and Saint

Stephen substituted for Isis and Harendotes. On the side doorway leading

to a room on the right is another inscription to Bishop Theodorus

claiming credit for this "good work".

At

the Grand Portico of the Temple of Philae and as depicted by David

Roberts in 1848. English novelist, journalist, traveller and

Egyptologist Amelia Edwards described it as "a place in which time seems

to have stood as still as in that immortal palace where everything went

to sleep for a hundred years. The bas-reliefs on the walls, the

intricate paintings on the ceilings, the colours upon the capitals are

incredibly fresh and perfect. These exquisite capitals have long been

the wonder and delight of travellers in Egypt. They are all studied from

natural forms - from the lotus in bud and blossom, the papyrus, and the

palm. Conventionalised with consummate skill, they are at the same time

so justly proportioned to the height and girth of the columns as to

give an air of wonderful lightness to the whole structure." Today

only ten columns remain. On the east side the reliefs were replaced by

Coptic Christian crosses where altars to the Virgin Mary and Saint

Stephen substituted for Isis and Harendotes. On the side doorway leading

to a room on the right is another inscription to Bishop Theodorus

claiming credit for this "good work".

Inside the sanctuary, Horus is depicted as hawk

wearing the Double Crown and standing in a thicket of papyrus. Below

that scene, Isis carries the newly born Horus in her arms, under the

protection of Thoth, Wadjet, Nekhbet and Amun-Ra. Successive pharaohs

reinstated their legitimacy as the mortal descendants of Horus by taking

part in rituals celebrating the Isis legend and the birth of her son

Horus in the marshes.

At the temple of Augustus from where archaeologists found a stone bearing a trilingual inscription referring to Cornelius Gallus (the first Roman Prefect appointed after the death of Cleopatra VII) in this temple recording the suppression of an Egyptian revolt in 29 BCE. From Egypt, the cult of Isis extended to Greece, Rome and throughout the Empire, so that when Roman rule was established in Egypt, successive Emperors embellished the sacred island. Besides Augustus who built this temple in 9 BCE, Tiberius and others added reliefs and inscriptions, and Claudius, Trajan, Hadrian and Diocletian erected new buildings up to the fourth century CE. It is assumed that Emperor Septimius Severus took the opportunity of carrying out the sollemne sacrum in person in late May of the year 200.

The Chapel of Horus on the north side of the Great Court of the Temple of Isis in a photo taken by Francis Bedford on March 13, 1862 during the 1862 travel of the Prince of Wales and today. Near Hadrian's Gate is the final datable text written in hieroglyphics dated August 24, 394CE, shown on the right.

In

front of the temple of Hathor, constructed by Ptolemy VI Philometor and

Ptolemy VIII Euergetes II. The temple included a colonnaded hall and a

small forecourt. The hall was decorated by Augustus with depictions of

the festivals in honour of Isis and Hathor where people eat, drink and

dance whilst Bes plays the harp and the tambourine (accompanied

by a number of apes who also play instruments or dance). Augustus is

also depicted presenting offerings to Isis and Nephthys.

In

front of the temple of Hathor, constructed by Ptolemy VI Philometor and

Ptolemy VIII Euergetes II. The temple included a colonnaded hall and a

small forecourt. The hall was decorated by Augustus with depictions of

the festivals in honour of Isis and Hathor where people eat, drink and

dance whilst Bes plays the harp and the tambourine (accompanied

by a number of apes who also play instruments or dance). Augustus is

also depicted presenting offerings to Isis and Nephthys.

In front of the so-called Trajan's Kiosk (sometimes referred to as

"Pharaoh's Bed"), one of the largest Ancient Egyptian monuments standing today. It is conventionally attributed to Trajan who gave it its

current decorations, although some believe the structure itself may be

older, dating to the time of Augustus. It had originally served as the main entrance into the temple from the river. Inside are reliefs showing Trajan as a pharaoh burning incense in honour of Isis and

Osiris and presenting wine to Isis and Horus. Its fourteen massive columns are adorned with carved floral capitals which were intended to be surmounted by sistrum capitals representing a percussion instrument that become a representative cult object of Hathor but which were never completed. Although today roofless, sockets within the structure's architraves suggest that its roof, which was made of timber, had been present in ancient times. Karnak

Karnak reconstructed and as it appears today with the wife and Drake Winston. The complex comprises a vast mix of decayed temples, chapels, pylons, and other buildings. Building at the complex began during the reign of Senusret I in the Middle Kingdom and continued into the Ptolemaic period, although most of the extant buildings date from the New Kingdom. The area around Karnak was the ancient Egyptian Ipet-isut ("The Most Selected of Places") and the main place of worship of the eighteenth dynasty Theban Triad with the god Amun as its head. It is part of the monumental city of Thebes. The Karnak complex gives its name to the nearby, and partly surrounded, modern village of El-Karnak, a couple of miles north of Luxor. One can see the remains of the mud brick ramps used to build it inside the great court when going through the main entrance into the temple. The north tower is roughly 71 feet and the south tower 103 feet; when completed it may have reached a height of as much as 131 feet. As seen in the background, an avenue of ram-headed sphinxes symbolising the god Amun leads to the entrance and into the first court.  The Avenue of Sphinxes at Karnak. The road from Luxor to Karnak was lined with recumbent rams, called Krio-Sphinxes, many of which still remain. Between their paws are small effigies of Ramesses II in the form of Osiris or standing figures of Amenophis III between their forelegs. In fact, the remains of some 850 fragmented sphinxes had already been discovered in recent years along an earlier section of Sphinx Alley which was built by the fabulously wealthy Pharaoh Amenhotep III. These statues were buried in the ground for a long time and were negatively affected by underground water making restoration particularly demanding. They were erected on either side of the road, alongside chapels stocked with offerings for the deities. Some 1,350 sphinx statues are thought once to have flanked the path and the Egyptian regime has allocated 600 million Egyptian pounds ($38 million) to restore the Grand Avenue of Sphinxes. Apart from being spent on actual digging, this money also went for the token compensation of the owners of the hundreds of buildings- homes, mosques (including one 350 years old) and churches constructed on the avenue over the centuries- that had been removed to clear the way for tracing the avenue.

The Avenue of Sphinxes at Karnak. The road from Luxor to Karnak was lined with recumbent rams, called Krio-Sphinxes, many of which still remain. Between their paws are small effigies of Ramesses II in the form of Osiris or standing figures of Amenophis III between their forelegs. In fact, the remains of some 850 fragmented sphinxes had already been discovered in recent years along an earlier section of Sphinx Alley which was built by the fabulously wealthy Pharaoh Amenhotep III. These statues were buried in the ground for a long time and were negatively affected by underground water making restoration particularly demanding. They were erected on either side of the road, alongside chapels stocked with offerings for the deities. Some 1,350 sphinx statues are thought once to have flanked the path and the Egyptian regime has allocated 600 million Egyptian pounds ($38 million) to restore the Grand Avenue of Sphinxes. Apart from being spent on actual digging, this money also went for the token compensation of the owners of the hundreds of buildings- homes, mosques (including one 350 years old) and churches constructed on the avenue over the centuries- that had been removed to clear the way for tracing the avenue.

In front of the First Court way station of Seti I which was designed to house the ceremonial boats for the Theban triad, consisting of the gods Amun, Mut and Khonsu. Nearby Drake stands before the colossal statue of Pinedjem I, High Priest of Amun at Thebes in Ancient Egypt from 1070 to 1032 BCE and de facto ruler of the south of the country from 1054 BCE. He had been the son of the High Priest Piankh although many Egyptologists today believe that the succession in the Amun priesthood actually ran from Piankh to Herihor to Pinedjem I

James Bond (accompanied by Ringo's wife Barbara Bach) at Karnak in The Spy Who Loved Me.

.gif) I was miraculously able to identify this single column of the 129 remaining in the Hypostyle Hall at Karnak and find a déroulé presenting the entire decoration of the same column produced by the Université du Québec à Montréal in collaboration with the University of Memphis. Each column inside the Hypostyle Hall are unique, both in terms of their scale and numbers, and also in the complexity of their decorative programme. It is the first building in ancient Egyptian architectural history to have columns inscribed from top to bottom with inscriptions. This unprecedentedly complex decorative programme, with multiple layers of reliefs, many of them palimpsests, is the work of no fewer than five kings who left their mark on the columns: Sety I, Ramesses II, Ramesses IV, Ramesses VI and, (more modestly) Herihor. The inscriptions each pharaoh left vary significantly both in terms of their position on the columns and the overall quantity of decoration. Their complex arrangement and chronology of these reliefs, many of them being palimpsests, follows the notion of “prime space” through which kings gave priority to sections of the columns most visible from the processional axes, and these were the first to be decorated. Understanding the successive phases of decoration on the columns is challenging. Ramesses II alone engraved them in four different stages, leaving palimpsests where he erased earlier decoration of Sety I and his own initial reliefs. Some columns have been inscribed and re-inscribed in six or seven phases during the Nineteenth and Twentieth Dynasties.

I was miraculously able to identify this single column of the 129 remaining in the Hypostyle Hall at Karnak and find a déroulé presenting the entire decoration of the same column produced by the Université du Québec à Montréal in collaboration with the University of Memphis. Each column inside the Hypostyle Hall are unique, both in terms of their scale and numbers, and also in the complexity of their decorative programme. It is the first building in ancient Egyptian architectural history to have columns inscribed from top to bottom with inscriptions. This unprecedentedly complex decorative programme, with multiple layers of reliefs, many of them palimpsests, is the work of no fewer than five kings who left their mark on the columns: Sety I, Ramesses II, Ramesses IV, Ramesses VI and, (more modestly) Herihor. The inscriptions each pharaoh left vary significantly both in terms of their position on the columns and the overall quantity of decoration. Their complex arrangement and chronology of these reliefs, many of them being palimpsests, follows the notion of “prime space” through which kings gave priority to sections of the columns most visible from the processional axes, and these were the first to be decorated. Understanding the successive phases of decoration on the columns is challenging. Ramesses II alone engraved them in four different stages, leaving palimpsests where he erased earlier decoration of Sety I and his own initial reliefs. Some columns have been inscribed and re-inscribed in six or seven phases during the Nineteenth and Twentieth Dynasties.

In

front of the central aisle of great hypostyle hall in the turn of the

20th century and today. The structure was built around the 19th Egyptian Dynasty and covers an area of 54,000 square feet. The

roof, now fallen, was supported by 134 columns in sixteen rows; the two middle

rows are higher than the others, being 33 feet in

circumference and 79 feet in height. The 134 papyrus columns

represent the primaeval papyrus swamp from which Amun, a self-created

deity, arose from the waters of chaos at the beginning of creating. The

hall was not constructed by Horemheb, or Amenhotep III as earlier

scholars had thought but was was initially instituted by Hatshepsut only to be built entirely by Seti I who engraved the northern wing of the hall with inscriptions. The decoration of the southern wing was completed by the 19th dynasty pharaoh Ramesses II. Greeks and Romans are known to have travelled to

Karnak which was a popular location on the tourist route in ancient

times, and many foreign visitors scratched their names or comments on

the Egyptian structures at which they marvelled. This graffiti not only

documents which buildings the curious tourists visited, but the scrawled

comments often attest to the participation of these travellers in cult

activities at the temple sites, such as consultation of oracles or

analysis of dreams.

In front of the Akhmenu during the war and today. The Akhmenu was the Great Festival Temple of Thutmose III which contained the chapel of ancestors containing a series of relief scenes depicting kings that Thutmose III, the king who built that structure, considered as his “ancestors.” Four rulers of the mid-Old Kingdom and one other whose name was destroyed are listed in this relief. Some Egyptologists interpret this depiction as a record of kings who contributed constructions to the earliest temple of Amun. The complex lies beyond an area of Middle Kingdom ruins. Its internal columns are unique with their inverted calyx capitals in the form of tent poles whilst within an antechamber is the so-called Botanical Garden, an area of reliefs recording plant, bird and animal species brought back from a campaign to Syria.

The state of Karnak when Napoleon’s expedition arrived in 1799 and today, showing how little has changed. As a military and colonial endeavour, the Egyptian campaign of 1798–1801 was a failure, yet it paradoxically ranks among Napoleon’s most significant achievements. Along with his soldiers, Napoleon also brought to 150 savants to systematically explore, describe, and document every aspect of the country. This select group of engineers, scientists, mathematicians, naturalists, and artists—called the Commission des Sciences et des Arts d’Égypte—was an integral part of the expedition by enhanced the expedition’s ideological goals through the rediscovery of the wonders of Pharaonic Egyptian civilisation, with which Napoleon was happy to be associated. It was this expedition which eventually led to the discovery of the Rosetta Stone, creating the field of Egyptology. Fortunately Napoleon and his Armée d'Orient were eventually routed by the British and forced to flee after suffering their historic defeat at the Battle of the Nile.

At

the site during the appallingly kitsch sound and light show ostensibly

recounting the history of Thebes and the lives of its pharaohs who built

here in honour of Amun. It culminates in

front of the Great Temple and the sacred lake, top, where, according to Herodotus, the priests of Amun bathed twice daily

and nightly for ritual purity. It also provided the home to the sacred geese of Amun. It had been dug by Tuthmosis III and 393 feet by 252 feet. It was also symbolically important as representing the primeval waters from which life arose. Below the seating erected for the sound and light show have been found the remains of the priests' homes, located on the eastern side of the lake, and which have been the subject of excavations since the 1970s.

In front of the seventh pylon are statues of Thutmosis III, shown bottom before the Great War and today.

On the right is the top of the second twin obelisk of Hatshepsut near the Sacred Lake which had toppled and broken in two. The pair had been built 1457 BCE during the XVIII dynasty and the standing partner is the second biggest of all the ancient Egyptian obelisks at a height of 28.58 metres and weighing 343 tonnes. As with all other Egyptian obelisks, they were carved from a single block stone, in this case usually pink granite from the distant quarries at Aswan. According to the inscription on the base it took seven months to quarry.

A

giant scarab in stone dedicated by Amenhotep III to Khepri, a form of

the sun god is shown during the day and when we revisited at night.

Tourists are told that walking around the scarab seven times brings

fortune. Such is the potency of this fad that it had to be relocated to

the lake's western side in order to make more space for such tourists.

On the path of El Kabash, also known as Sphinx Alley, a two-mile avenue that connected the temples of Luxor and Karnak, marking a route that ancient Egyptians promenaded along once a year carrying the statues of the deities Amun and Mut in a symbolic re-enactment of their marriage. These statues of sphinxes were carved from a single block of sandstone and engraved with the name Allmk had the heads of a rams which symbolised the god Amun. Amun was ancient Egypt's supreme god king, whilst Mut was a goddess worshipped as a mother. The road was later used by the Romans and is believed to have been renovated by Cleopatra, the fabled Ptolemaic queen who left her cartouche - an inscribed hieroglyphic bearing her name - here at the temple in Luxor.

On the path of El Kabash, also known as Sphinx Alley, a two-mile avenue that connected the temples of Luxor and Karnak, marking a route that ancient Egyptians promenaded along once a year carrying the statues of the deities Amun and Mut in a symbolic re-enactment of their marriage. These statues of sphinxes were carved from a single block of sandstone and engraved with the name Allmk had the heads of a rams which symbolised the god Amun. Amun was ancient Egypt's supreme god king, whilst Mut was a goddess worshipped as a mother. The road was later used by the Romans and is believed to have been renovated by Cleopatra, the fabled Ptolemaic queen who left her cartouche - an inscribed hieroglyphic bearing her name - here at the temple in Luxor. The Karnak Temples are the largest temple complex inEgyptand are located inKarnak, a village about 2.5 kilometers north ofLuxorand directly on the easternbank of the Nile. The oldest remains of the temple still visible today date from the12th DynastyunderSesostris I. [ 1 ] The temple complex was repeatedly expanded and rebuiltuntil theRoman Empire . Columns of thehypostyleinthe Temple of Amun-Re Temple complex of Karnak The entrance area to the Karnak Temple The temple complex has been on the UNESCO World Heritage List since 1979 , together with theLuxor Templeand theThebanNecropolis . [ 2 ] Table of contents The temple complex View from the air Outstanding among theruinsis theTemple of Amun-Rewith its tenpylons, the largest of which is about 113 meters wide and about 15 meters thick and has a planned height of about 45 meters. The total area of the temple is about 30 hectares (530, 515, 530 and 610 meters side length). [ 3 ] In addition to the pylons, the large columned hall, which was started byHaremhaband completed underSethos IandRamses II, is particularly impressive. Statue of Ramses II with daughterMeritamun The temple complex consists of three walled areas, the district ofAmun(ancient Egyptian Ipet-sut , "place of election"), the district ofMonth(150 × 156 meters, total area 2.34 hectares) and the district ofMut(405, 275, 295 and 250 meters side length, total area approx. 9.2 hectares). In addition to these three large temple districts, there is also theAtontemple, theGem-pa-Aton, whichAkhenatenhad built in Karnak in the sixth year of his reign. In ancient times, anavenuelined on both sides by 365sphinxes [ 4 ] connected the Amun temple with the Luxor temple, about 2.5 km away . This road ends at the 10th pylon of the temple. Purpose of the temple complex AnusAmun-ReofThebeswas elevated to the status of local god and later to the status of empire god, the rulers of theearly Middle Kingdombegan to build a temple, which was expanded over thousands of years to become the current temple complex, where theAmun priesthoodperformed daily temple services. Temples were also built for Amun's wife, the goddessMut, and for their sonKhonsu; together they formed thetriadof Thebes. In addition to these three gods, a temple was also dedicated to the godMonth, who was the main god of Thebes in the11th Dynasty. Upper part of Hatshepsut's obelisk at the Sacred Lake In the ancient Egyptian belief system, there is the principle ofcosmologicalorder, this principle is calledMaat. Since Maat is not an unchangeable state and can be thrown out of balance by people, it is important to maintain this state in order to keep chaos and destruction away from the world. An Egyptian temple represents a model of the world. One of the king's highest duties was therefore to maintain the balance of mate. This took place in the holiest area of the temple. In the temple, sacred cult acts (sacrifices, prayers and songs) were carried out by the king or thehigh priestrepresenting him . Construction history The earliest evidence of an Amun cult in Thebes comes from theMiddle Kingdom. It is an octagonal column ofAntef II, which is now in theLuxor Museum. The oldest building remains still visible today date from the time ofSesostris I.In theNew Kingdomthere was a lot of building activity and the temple complex soon reached enormous dimensions. The temple was also built in theLateandGreco-Roman periods. Districts of the Karnak Temple Complex District of Amun Amun-Re Temple in Karnak The largest area of the complex is the Precinct of Amun . It houses the largestTemple of Amun-Re, theTemple of Khonsu, the barque sanctuary of Ramses III, a temple ofIpet, and a small sanctuary of Ptah as well as the Temple of Amenhotep II. Temple of Amun-Re → Main article :Temple of Amun-Re (Karnak) The Temple of Amun-Re, also known as the Imperial Temple, [ 5 ] is the largestEgyptian templewith a total of ten pylons. It is not a temple in the classical sense, but rather a collection of various sacred buildings built next to one another. Various parts of the temple were demolished and their building materials reused in other parts. Only the center of the temple, from the fourth pylon to the Ach-menu, remained untouched as a particularly sacred area. Columns of thehypostyle Reconstruction of the Column Hall One of the most important areas of the temple is the large hypostyle hall,which Horemheb began to build between the second and third pylons and which was later completed under Seti I and Ramses II. [ 6 ] On an area of 103 meters long and 53 meters wide there once stood 134papyrus columnsthat supports the wooden roof of the hypostyle. In the central nave of the hall the columns were up to 22.5 meters high. Ach-menu Also worth mentioning is the Ach-menu or festival temple ofThutmosis III , which bears the ancient Egyptianname Men-cheper-Ra-ach-menu: "Magnificent among monuments is Men-cheper-Ra" (Thutmosis III) or "Exalted is the memory of Men-cheper-Ra". [ 7 ] In addition to these names, the termMillion-Year Housecan also be found, which suggests that the temple was dedicated to the cult of the king in his manifestation as Amun-Re. Kioskof the Taharqa Thearchitecturallystriking festival hall is often referred to as a festival tent due to the arrangement of its columns. The higher central space consists of two rows of columns with ten columns each and is surrounded by lower side aisles with a total of 32 columns. [ 8 ] At the entrance to the Ach-menu is the so-calledKing List of Karnakwith the names of a total of 61 kings. The Ach-menu lies on the east-west axis of the temple district, but the structural arrangement also takes the north-south axis into account. In the rear part are the sanctuaries for the godsSokar(south) and Amun-Re (north). Next to the festival temple of Thutmose III is thekioskof theTaharqa. During the restoration of the third pylon of the temple, built by Amenhotep III, building materials from theWhite Chapel, theRed Chapeland theAlabaster Chapelwere discovered. [ 3 ] North of the Amun-Re Temple, the White Chapel of Sesostris I, the oldest surviving building in the complex, and the Alabaster Chapel were reconstructed in the20thcentury from recovered building materials. At the beginning of the21st century,the Red Chapel ofHatshepsutso what was rebuilt here. The third pylon was originally about 98 meters long and about 14 meters wide. Since it is now badly damaged, only about a quarter of its original height of about 35 meters has been preserved. White Chapel → Main article :White Chapel White Chapel The White Chapel (also Chapelle blanche) was built in the 12th Dynasty by Sesostris I from whitelimestone. It is the oldest surviving building in the temple complex. On a 1.18 meter high base is a 6.54 × 6.54 meterkiosk, the roof of which is supported by four by fourpillars . [ 9 ] The White Chapel was built as a barque sanctuary and thus served as a station chapel for the barque of the godsduring various festivities . The White Chapel, like the Red Chapel and the Alabaster Chapel, stood in the area between the third and seventh pylons. The chapel was rebuilt in the open-air museum of Karnak. Red Chapel → Main article :Red Chapel (Karnak) Red Chapel The Red Chapel was built by QueenHatshepsutin the18th Dynasty. The chapel originally stood in the area between the third and seventh pylons. Later, the chapel, built as a barque sanctuary, was demolished by Thutmose III.Amenhotep IIIhad the blocks used as filling material for the third pylon. During restoration work, 319 blocks of blackgraniteand redquartzitefrom the chapel were discovered. [ 10 ] The Red Chapel was rebuilt from this material in the open-air museum of the temple complex. The sculptures in the Red Chapel show the coronation of Hatshepsut, sacrificial scenes and Theban festivals such as the Opet Festival. [ 11 ] The chapel also houses the oldest depiction of this festival. Alabaster Chapel Alabaster Chapel The Alabaster Chapel, built in the 18th Dynasty as a barque sanctuary ofThutmosis IV,probably stood, like the Red and White Chapels, in the area between the third and seventh pylons. Temple of Ramses III. In the courtyard behind the first pylon, on the right-hand side, is the Temple ofRamses III.It is still almost completely preserved and in very good condition. Behind a pylon with twocolossal figuresin front of it is the festival courtyard, lined on each side by eight statue pillars. Following the courtyard is a small hall with four statue pillars. This is followed by the hypostyle with two by four columns. Behind the hypostyle are three sanctuaries dedicated to the gods Amun-Re, Mut and Khonsu. The similarity to Temple C in the Mut district is striking. [ 12 ] [ 13 ] Holy Lake Holy Lake Thesacred lakehas a size of 120 × 77 meters and is located south of the central temple building. [ 14 ] This lake has no supply pipes, it is only fed bygroundwater. Next to the lake there was a small covered goose enclosure that was connected to the lake by a corridor. Thegeesewere the sacred animals of Amun. The priests also took water from the lake to wash the figures of the gods. Temple of Opet The Temple of Opet was built in the Ptolemaic period byPtolemy VIII.Through a staircase in a kiosk with four columns, one enters the first courtyard through the gate of the first pylon. In the first courtyard there is another kiosk, also with four columns. The second courtyard is higher up, which is probably like thatprimeval moundis depicted. [ 15 ] In the rear part of the temple there is an undergroundOsiris tomband acrypt, here themetamorphosisof the god Amun-Re took place, who died asOsiris, then entered the body ofIpet-weret-Nutand was reborn as the god Khonsu. Temple of Khonsu → Main article :Temple of Khonsu (Karnak) Pylon of the Khonsu Temple Great pillared hall of the temple The Temple of Khonsu is located on the southern edge of the Amun precinct, it is about 80 meters long and 30 meters wide. The temple is located directly opposite the Luxor Temple. During the 20th Dynasty, the temple was built under Pharaoh Ramses III and later completed byRamses IV,Ramses XIandHerihor . Behind the large entrance pylon is a large columned hall with 28 columns. [ 16 ] This is followed by a hypostyle with eight large columns and finally the center, the so-calledHall of the Barque. Temple of Ptah Gate in the Ptah Temple The Temple of Ptah is located on the north wall of the Amun precinct and was originally surrounded by a wall. With the construction of the large wall around the Amun precinct, the size of the forecourt to the temple was reduced.Ptolemy IIIbuilt the small pylon of the temple, which contains various interior rooms. In front of the pylon is a small kiosk. The rest of the temple was built under Thutmose III. All parts of the temple that were built from stone are completely preserved. [ 17 ] Temple of Amenhotep II Behind the tenth pylon, on the east side, is the temple ofAmenhotep II.Arampleads to the entrance area, which is an open pillared hall. Behind the pillared hall is a square hypostyle. To the north and south of the hypostyle are further small rooms. The latest research has shown that it was not Amenhotep II who had the temple built in its current form, but that Seti I had built it using building materials from a demolished building of Amenhotep II. [ 18 ] District of the Month To the north, directly next to the large area ofAmun-Re, there is a 151 × 155 m area with the temple district of Month. Thesurrounding walldates from the time ofNectanebo I.The actual temple was built by Amenhotep III. Next to theTemple of Monththere is a Temple ofMaat, a Temple ofHarpare, built byTaharqa, and the treasury of Thutmose I, which lies outside the surrounding wall. [ 19 ] The Temple of Month opens towards the Month cult site al-Madamud,which is about five kilometers away. From the temple entrance, an avenue of sphinxes with 30 human-headed sphinxes on each side [ 4 ] leads to a quay that is no longer connected to the water. [ 20 ] District of Courage Statue ofSekhmetin the Mut district About 350 m south of the Amun-Re Temple lies an area of approximately 250 × 350 meters, which includes the district of Mut. It was connected to the Temple of Amun-Re by an avenue of sphinxes with 66 sphinxes [ 4 ] . Next to the Temple of Mut, which is surrounded on three sides by a sacred lake, there are still remains of a birthplace (Mammisi) of Ramses II for "Chonspachrod" (actually: Chonsu-pa-chered - "Chons, the child"), remains of a temple of Ramses III and outside the wall of the Kamutef temple. In 1840, most of the temples were demolished and used as building material for a factory. [ 21 ] Temple of Courage The entrance pylon of the Temple of Mut was built bySethos II. In front of the pylon there were two shade roofs supported by columns, built byTaharqa. [ 22 ] In the courtyard behind the first pylon, a colonnade is formed by four columns on either side of its central axis. Through the gate in the second pylon one enters the festival courtyard, where the colonnade is continued by five columns on either side. In both courtyards there were once seated statues of the goddess Sekhmet. Behind the festival courtyard one enters the hypostyle, the ceiling of which was originally supported by eight columns. Behind the hypostyle is the barque sanctuary. The barque sanctuary was surrounded by several side rooms. Through the barque sanctuary one enters thepronaos, an anteroom to thesanctuary. The sanctuary of the temple consists of three cult image niches.Ptolemy IIbuilt acounter-templeagainst the back wall of the temple. The temple was largely demolished in 1840. [ 21 ] Temple A Temple A is located east of the Mut Temple, to the right of the main gate directly behind the surrounding wall. According toDieter Arnold,Temple A was built byRamses II [ 21 ] , according to Paul Barguet byThutmosis IV. [ 23 ] The first of the three pylons was built from Nile mud bricks. Two statues there bear the name of Ramses II, but were probablyusurped. In the second pylon, stone blocks from the18thto22nd dynastieswere reused. The third pylon is again attributed to Ramses II, the decorations date from his time. There are also different views on the significance of the temple. According to Daumas, it is a barque sanctuary dedicated to Khonspachrod (Khons the Child), [ 24 ] according to Arnold, it is a birthplace for Khonspachrod. [ 22 ] Unfortunately, the few surviving paintings and reliefs do not allow for a more precise identification. Temple C West of the Sacred Lake, also calledAsheruor Iseru, lies the so-called Temple C.Ramses IIIhad the temple, dedicated to Amun, Mut and Khonsu, built in the20th Dynasty. Two monumental statues of Ramses III originally lined the entrance in the first pylon of the temple. In the festival courtyard behind the first pylon, there were eight statues on the right and left sides. A ramp led to a small pillared vestibule at the end of the festival hall and the hypostyle, whose ceiling was supported by four pillars. There were three storage rooms on each side of the hypostyle. Through the hypostyle one entered an anteroom, which was followed by the three sanctuaries. The temple is badly damaged, but Ramses III was clearly identified as its builder based on theHarris I Papyrus . [ 25 ] Temple of Kamutef Kamutef Temple The Kamutef Temple, built by Hatshepsut, stands to the northeast, directly in front of the walled temple precinct of Mut, on the 330-meter-long Avenue of Sphinxes with 66 sphinxes on both sides. [ 4 ] The stone temple house is approximately 38.5 × 48.5 meters in size. The temple house was surrounded by a brick wall that opened into a pylon on the Avenue of Sphinxes. [ 26 ] Thutmose III later tried to destroy all evidence of the original builder, but the reliefs show that Hatshepsut was responsible for their installation. Gem-pa-Aton → Main article :Gem-pa-Aton (Karnak) Restored Talatat blocks from the Gem-pa-Aton To the east of the Amun precinct was anAtensanctuary (ancient Egyptian Gm-p3-Jtn , "the Aten is found"), which was probably built byAkhenatenin the 6th year of his reign. The Aten temple was about 130 × 200 meters in size, at that time it was larger than the Temple of Amun. [ 27 ] Akhenaten ordered the closure of the other temples in Karnak and elevated the sun god Aten to the sole god. After the original conditions were restored underHaremhab at the latest, the other temples of Karnak were reopened and the Gem-pa-Aton was completely demolished. Tens of thousands of the Talatatblocks were reused as filling material in the buildings of Horemheb and his successors and have therefore been well or very well preserved. These blocks were mainly used for pylons 2, 9 and 10. In the Luxor Museum, several hundred of these blocks have been restored and reassembled.

Beyond the first pylon Ramesses II built a peristyle courtyard (replacing an earlier court thought to have been constructed by Amenhotep III) which was set at an angle to the rest of the temple in order to preserve three pre-existing barque shrines constructed by Hatshepsut (with later additions) which stand in the northwest corner. The court is composed of a colonnade including a number of colossal statues of Amenhotep III which were usurped by Ramesses II. The Abu'l Hagag mosque perches precariously at the top of the columns of this courtyard. As a result one of the doorways, on the eastern side, hovers uselessly above the ground. The peristyle courtyard leads to the processional colonnade built by Amenhotep III with additional decorations added by Tutankhamen, Horemheb and Seti I. By entrance to the colonnade there are two statues representing Tutankhamun, but on each his name has been replaced by that of Ramesses II. It is lined with fourteen huge papyrus topped columns and the walls are decorated with scenes depicting the stages of the Opet Festival. Other decorations celebrate the reinstatement of Amun and the other traditional gods following the Atenist heresy. They are ascribed to Tutankhamun, but his name has been erased and replaced by that of Horemheb.

.gif) Standing inside the court of Ramesses II and a reconstruction. The courtyard is surrounded by a double colonnade consisting of papyrus bundle columns with closed capitals. In the western part there is a so-called 'three-aisled station chapel' of Queen Hatshepsut. The three rooms are dedicated to the gods Mut, Amun and Khons. The walls of the courtyard are decorated with sacrificial scenes and the procession of the sons of Ramses II. In the back there are statues that bear the name of Ramses II, but are actually of Amenhotep III. The colonnade of closed papyrus-bud columns, which originally lined the court on all four sides, is today interrupted in the northeast corner by the presence of the mosque of Abu el-Haggag. This part of Luxor Temple was converted to a church by the Romans in 395, and then to a mosque in 640. The site therefore has seen 3,400 years of continuous religious use, making Luxor Temple the oldest building in the world at least partially still in use for purposes other than archeological or tourism, making it one of the oldest continuously used temples in the world, dating back to the reign of Pharaoh Amenhotep III in the 14th century BCE. Occupying most of the spaces between the columns are standing statues of Ramesses II; the crowns of several of these figures can be seen lying on the ground beside them because they had been carved separately and subsequently fell off.

Standing inside the court of Ramesses II and a reconstruction. The courtyard is surrounded by a double colonnade consisting of papyrus bundle columns with closed capitals. In the western part there is a so-called 'three-aisled station chapel' of Queen Hatshepsut. The three rooms are dedicated to the gods Mut, Amun and Khons. The walls of the courtyard are decorated with sacrificial scenes and the procession of the sons of Ramses II. In the back there are statues that bear the name of Ramses II, but are actually of Amenhotep III. The colonnade of closed papyrus-bud columns, which originally lined the court on all four sides, is today interrupted in the northeast corner by the presence of the mosque of Abu el-Haggag. This part of Luxor Temple was converted to a church by the Romans in 395, and then to a mosque in 640. The site therefore has seen 3,400 years of continuous religious use, making Luxor Temple the oldest building in the world at least partially still in use for purposes other than archeological or tourism, making it one of the oldest continuously used temples in the world, dating back to the reign of Pharaoh Amenhotep III in the 14th century BCE. Occupying most of the spaces between the columns are standing statues of Ramesses II; the crowns of several of these figures can be seen lying on the ground beside them because they had been carved separately and subsequently fell off. .gif) Eventually in the middle of the 3rd century the temple was transformed into a castrum, the old cult had been effectively abandoned as clearly shown by the Greek graffiti inside the temple. This camp housed the legion in charge of defending the limes located further south in Aswan against the Blemmyes, a nomadic peoples who had seized Lower Nubia. The enclosure wall was rebuilt and fortified gates were built there, notably by reusing elements of the disused temple, going so far as to completely cut up a colossus of Ramesses II to obtain blocks intended to serve as lintels and architraves at the gates which guard the fortress. A veritable garrison town developed inside the enclosure, with its roads intersecting at right angles delimiting the districts or insulae in which forums and basilicas were built. The Romans didn't touch the pharaonic temple as a whole but rather it seems that the great court of Amenhotep III and the hypostyle hall were used as the headquarters of the legions. A Roman chapel is installed in the second hypostyle hall of the sanctuary, which served as a vestibule for the resting place of the boat. The door originally leading to the room reserved for it was then closed and replaced by a large apse in a cul-de-four flanked by two granite columns with monolithic barrels and composite capitals. The walls decorated with reliefs from the 18th dynasty are covered with plaster and decorated with frescoes representing the sovereigns, their court and scenes of military victory.

Eventually in the middle of the 3rd century the temple was transformed into a castrum, the old cult had been effectively abandoned as clearly shown by the Greek graffiti inside the temple. This camp housed the legion in charge of defending the limes located further south in Aswan against the Blemmyes, a nomadic peoples who had seized Lower Nubia. The enclosure wall was rebuilt and fortified gates were built there, notably by reusing elements of the disused temple, going so far as to completely cut up a colossus of Ramesses II to obtain blocks intended to serve as lintels and architraves at the gates which guard the fortress. A veritable garrison town developed inside the enclosure, with its roads intersecting at right angles delimiting the districts or insulae in which forums and basilicas were built. The Romans didn't touch the pharaonic temple as a whole but rather it seems that the great court of Amenhotep III and the hypostyle hall were used as the headquarters of the legions. A Roman chapel is installed in the second hypostyle hall of the sanctuary, which served as a vestibule for the resting place of the boat. The door originally leading to the room reserved for it was then closed and replaced by a large apse in a cul-de-four flanked by two granite columns with monolithic barrels and composite capitals. The walls decorated with reliefs from the 18th dynasty are covered with plaster and decorated with frescoes representing the sovereigns, their court and scenes of military victory.