Hitler's Bunker and Chancellery has its separate entry

Wilhelmstraße as depicted in the final days of the war in the film Der Untergang and during my Bavarian International School class trip in 2020

Walking down Wilhelmstraße and the same spot during the Nazi era, with Hitler's Chancellery seen in the background. Site of the Third Reich's most important ministries and embassies, until 1945, the rhetorical expression Wilhelmstraße was a metonym for

the German Reich government, similar to Downing Street. Apart

from the Air Ministry, all the major public buildings along Wilhelmstraße were destroyed by Allied bombing during 1944 and early

1945.

Walking down Wilhelmstraße and the same spot during the Nazi era, with Hitler's Chancellery seen in the background. Site of the Third Reich's most important ministries and embassies, until 1945, the rhetorical expression Wilhelmstraße was a metonym for

the German Reich government, similar to Downing Street. Apart

from the Air Ministry, all the major public buildings along Wilhelmstraße were destroyed by Allied bombing during 1944 and early

1945. Despite

such severe destruction by the Anglo-American air raids and the

Battle of Berlin, numerous historic buildings on Wilhelmstraße have

been preserved; the Berlin monument list names nineteen sites worthy of protection. Wilhelmstraße as far south as Zimmerstrasse was in the Soviet Zone of

occupation, and apart from clearing the rubble from the street little

was done to reconstruct the area until the founding of the DDR in 1949

when a large part of the area was built over with prefabricated buildings. The East German regime regarded the former government precinct as a

relic of Prussian and Nazi militarism and imperialism, and had all the

ruins of the government buildings demolished in the early 1950s. In the

late 1950s there were almost no buildings at all along the Wilhelmstraße from Unter den Linden to the Leipziger Strasse. In the

1980s, apartment blocks were built along this section of the street.

On

the area of the former Prinz-Albrecht-Palais is the new building of

the Topographie des Terrors Foundation which opened in 2010 and tries to

present the street with its historical references under the heading of

the Wilhelmstraße History Mile. On the initiative of the Berlin House of

Representatives, a permanent street exhibition with glass information

boards has been erected to show the locations of earlier institutions

since the early 1990s. Several new buildings are planned on Wilhelmstraße including the “Palais an den Ministergärten” along

Cora-Berliner-Strasse, for which several temporary snack bars are being

demolished.

Wilhelmstraße 62: Reichskolonialamt

Site of the former headquarters of the Reich Colonial office, set up to reclaim the colonies lost through the treaty of Versailles. It was originally created by decree by Kaiser Wilhelm II on May 17, 1907 as a central authority in its own right, managed by a cabinet-level Secretary of State. It had then been physically relocated to this site near Wilhelmplatz, where the Colonial Department of the Foreign Office had resided since 1905. This legislation had represented a complete reorganisation and was a direct response to the nationwide so-called "Hottentot election", after allegations of colonial malfeasance, corruption and brutality as a result of the Herero and Namaqua Genocide in German South-West Africa surfaced in the German media and culminated in the dissolution of the Reichstag parliament. The shake-up subsequently involved extensive and wide-ranging personnel changes in civil service positions in the colonies.

Site of the former headquarters of the Reich Colonial office, set up to reclaim the colonies lost through the treaty of Versailles. It was originally created by decree by Kaiser Wilhelm II on May 17, 1907 as a central authority in its own right, managed by a cabinet-level Secretary of State. It had then been physically relocated to this site near Wilhelmplatz, where the Colonial Department of the Foreign Office had resided since 1905. This legislation had represented a complete reorganisation and was a direct response to the nationwide so-called "Hottentot election", after allegations of colonial malfeasance, corruption and brutality as a result of the Herero and Namaqua Genocide in German South-West Africa surfaced in the German media and culminated in the dissolution of the Reichstag parliament. The shake-up subsequently involved extensive and wide-ranging personnel changes in civil service positions in the colonies.

Between 1893 and 1903, the Herero and Nama people's land and cattle were progressively being taken by German colonists. The Herero and Nama resisted expropriation over the years, but they were disorganised and easily defeated. In 1903, the Herero discovered that they were to be placed in reservations, leaving more room for colonists to own land and prosper. In 1904, the Herero and Nama began a great rebellion that lasted until 1907, ending with the near destruction of the Herero people. According to Frank Chalk and Kurt Jonassohn, "[t]he war against the Herero and Nama was the first in which German imperialism resorted to methods of genocide...." Roughly 80,000 Herero lived in German South West Africa at the beginning of Germany's colonial rule over the area, whilst after their revolt was defeated, they numbered approximately 15,000. According to the 1985 UN Whitaker Report on Genocide, within a period of four years, approximately 65,000 Herero people perished. This was to constitute the first genocide of the 20th century, waged by the Germans against the Ovaherero, the Nama, and the San in German South West Africa (now Namibia). The BBC documentary Namibia – Genocide & the Second Reich explores the Herero/Nama genocide and the circumstances surrounding it. A student examined this topic for his IBDP Extended Essay in History, receiving an 'A'.

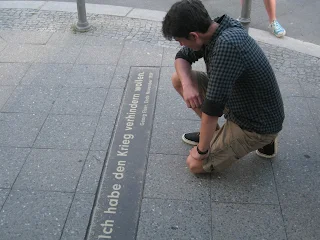

The ministry itself was eventually dissolved after the Great War on February 20, 1919 and replaced by the Imperial Colonial Ministry (Reichskolonialministerium) of the Weimar Republic, dealing with settlements and closing-out of affairs of the occupied and lost colonies. The building itself had been demolished in 1938; students are shown on the right during my 2020 Bavarian International School class trip beside a sign at the site mentioning the Herero, but without a word about the genocide.

The ministry itself was eventually dissolved after the Great War on February 20, 1919 and replaced by the Imperial Colonial Ministry (Reichskolonialministerium) of the Weimar Republic, dealing with settlements and closing-out of affairs of the occupied and lost colonies. The building itself had been demolished in 1938; students are shown on the right during my 2020 Bavarian International School class trip beside a sign at the site mentioning the Herero, but without a word about the genocide.

Unter Den Linden 72-73: Reichsinnenministerium

The Reich Ministry of the Interior (RMI) was the interior ministry of the German Empire during the Weimar Republic and the Nazi regime. On November 1, 1934 it was combined with the Prussian Ministry of the Interior to form the Reich and Prussian Ministry of the Interior. In particular, it was responsible for the entire police apparatus. It was the successor to the Federal Chancellery of the North German Confederation from 1867, called the Reich Chancellery since 1871 , and the Reich Office of the Interior from 1879 as well as the predecessor of the Federal Ministry of the Interior. From 1837 two buildings together housed the Prussian Interior Ministry, which Hermann Goering assumed control of in 1933. Through it he controlled the Prussian police force numbering 50,000 'auxiliary policemen', mostly recruited form the SA and ϟϟ and used to persecute opponents. On November 1, 1934 it was merged with the Reich Interior Ministry headed by Wilhelm Frick who was responsible for drafting many of the "Gleichschaltung" laws that consolidated the Nazi regime and was instrumental in passing laws against Jews such as the notorious Nuremberg Laws, in September 1935. He was succeeded in the post in 1943 by Himmler. Stephan Lehnstaedt's Das Reichsministerium des Innern unter Heinrich Himmler 1943–1945 can be found here.

The Reich Ministry of the Interior (RMI) was the interior ministry of the German Empire during the Weimar Republic and the Nazi regime. On November 1, 1934 it was combined with the Prussian Ministry of the Interior to form the Reich and Prussian Ministry of the Interior. In particular, it was responsible for the entire police apparatus. It was the successor to the Federal Chancellery of the North German Confederation from 1867, called the Reich Chancellery since 1871 , and the Reich Office of the Interior from 1879 as well as the predecessor of the Federal Ministry of the Interior. From 1837 two buildings together housed the Prussian Interior Ministry, which Hermann Goering assumed control of in 1933. Through it he controlled the Prussian police force numbering 50,000 'auxiliary policemen', mostly recruited form the SA and ϟϟ and used to persecute opponents. On November 1, 1934 it was merged with the Reich Interior Ministry headed by Wilhelm Frick who was responsible for drafting many of the "Gleichschaltung" laws that consolidated the Nazi regime and was instrumental in passing laws against Jews such as the notorious Nuremberg Laws, in September 1935. He was succeeded in the post in 1943 by Himmler. Stephan Lehnstaedt's Das Reichsministerium des Innern unter Heinrich Himmler 1943–1945 can be found here.

The

Federal Chancellery of the North German Confederation had been located

at Wilhelmstrasse 74 since 1867. The Ministry, renamed the Reich

Ministry of the Interior , moved in 1919 to Königsplatz in the

Alsenviertel in the former General Staff Building (today Platz der

Republik ). During the war the building was destroyed and eventually

blown up in 1950 and 1951.

The

building itself was constructed from 1935 to 1937 to a design by Konrad Nonn who had been a Nazi party member and activist of the Kampfbund Deutscher Architekten und Ingenieure. It was one of the first government buildings erected by the Nazis.

The

building itself was constructed from 1935 to 1937 to a design by Konrad Nonn who had been a Nazi party member and activist of the Kampfbund Deutscher Architekten und Ingenieure. It was one of the first government buildings erected by the Nazis.

Architecture was not the only aspect of Nazi rule that survived. As Paul Meskil wrote in 1961 in his book Hitler's Heirs: Where Are They Now? (112):

Annex

of the former Reich Ministry of the Interior at Dorotheenstraße 93,

later used by the East German Ministry of Justice and now by the

Bundestag. After reunification Dorotheenstraße, named after the Great Elector's wife, replaced

the DDR's Clara-Zetkinstraße. Zetkin, who was Jewish, spent four

decades as a Social Democrat and became an internationally recognised

feminist, but after 1919 joined the Communist Party and denounced the

Weimar Republic. The new authorities declared that the street leading

from eastern Berlin to the Reichstag could not be named after an

opponent of parliamentary democracy as leftists and feminists organised

marches in protest.

The threat to Zetkin and other idols of the left redounded to the benefit of the ex-Communist PDS, which emerged as eastern Berlin's strongest party in 1994 elections by appealing to the separate identity of misunderstood Ossis. To the frustration of some commission members, the government had restricted its purview to the former East Berlin, effectively limiting its purge to leftist opponents of Weimar democracy.

Ladd (211) Ghosts of Berlin

The

building itself was constructed from 1935 to 1937 to a design by Konrad Nonn who had been a Nazi party member and activist of the Kampfbund Deutscher Architekten und Ingenieure. It was one of the first government buildings erected by the Nazis.

The

building itself was constructed from 1935 to 1937 to a design by Konrad Nonn who had been a Nazi party member and activist of the Kampfbund Deutscher Architekten und Ingenieure. It was one of the first government buildings erected by the Nazis.Architecture was not the only aspect of Nazi rule that survived. As Paul Meskil wrote in 1961 in his book Hitler's Heirs: Where Are They Now? (112):

[Chancellor Konrad] Adenauer's chief personal aide is Dr. Hans Globke, State Secretary of the Bonn Chancellery. Though not a member of the Nazi Party, he was a high official of the Nazi Interior Ministry and co-author of a legal interpretation of the 1935 Nuremberg racial laws. Those laws, defining a Jew as anyone with a Jewish grandparent, laid the legal basis for the persecution of all Jews in Germany.

Wilhelmstraße 64: Central Office of the Führer's Deputy

(Rudolf Hess's HQ)

Wilhelmstraße 65: Reichsjustizministerium

Under the Nazis the Prussian Ministry of Justice was merged with the Reich Ministry of Justice and headed by Franz Gürtner who was responsible for coordinating jurisprudence in the Third Reich. Objecting to the illegality of the Gestapo and SA in dealing with prisoners of war, he protested unsuccessfully to Hitler, nevertheless staying on in the cabinet, hoping to reform the establishment from within. Instead, he found himself providing official sanction and legal grounds for a series of criminal actions under the Hitler administration. His successor, Otto Thierack, forwent any pretence of legality and simply began handing undesirable groups over to the ϟϟ having come to an understanding with Himmler that certain categories of prisoners were to be, to use their words, "annihilated through work". Lengthy paperwork involved in clemency proceedings for those sentenced to death was greatly shortened and, at his personal instigation, the execution shed at Plötzensee Prison in Berlin was outfitted with eight iron hooks in December 1942 so that several people could be put to death at once by hanging. At the mass executions beginning on September7, 1943, it also happened that some prisoners were hanged "by mistake". Thierack simply covered up these mistakes and demanded that the hangings continue. During the war an air raid in December 1944 destroyed the main building except for the surrounding walls. The

building was demolished in 1950 and the property was initially kept free for a passage from Französische Strasse to Wilhelmstrasse. Today the site serves as the embassy of Afghanistan.

Wilhelmstraße 68: Reichsministerium für Wissenschaft, Erziehung und Volksbildung

The Reich Ministry of Science and Public Education in July, 1943 and the site today. After the Nazis came to power Bernhard Rust, Gauleiter of South Hanover-Braunschweig, was appointed provisionally as Prussian Minister of Education. After responsibility for arts affairs had been transferred to the Reich Ministry for Public Enlightenment and Propaganda, Rust was appointed Reich Minister for Science, Education and Public Education on May 1, 1934 and tried to bring the school system into line with Nazi ideology whilst discharging those regarded as politically or racially "undesirable" from scientific and research work. The Prussian Ministry of Culture served as the basis of the newly created Reich Ministry, whose officials also dealt with the affairs of the Reich. At the beginning of 1935, the name of the ministry was adapted accordingly and the authority now operated as the Reich and Prussian Ministry for Science, Education and National Education (Reich Ministry of Education or REM). On October 1, 1938, the reference to Prussia was deleted and the Ministry finally renamed the Reich Ministry for Science, Education and National Education. During the war the building complex was destroyed with the exception of the eastern courtyard wing and parts of the connecting passage to the extension. In August 1945, some of its rooms were set aside for the German Central Authority for Public Education. In October 1949 upon the official creation of the DDR, this became the East German Ministry of Public Education. From 1963 until 1989 the ministry was headed by the wife of East Germany's last Head of State, Margot Honecker. From 1970 until the dissolution of East Germany in 1990 it housed the East German Academy of Educational Science. Today it serves as offices for members of the Bundestag.

Wilhelmstraße 70: Embassy of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland

(Rudolf Hess's HQ)

Wilhelmstraße 64 then and standing in front in 2020. Built by Carl Vohl in 1903, the building used to be the liaison office of the Prussian king and the kaiser to the government, housing the Privy Civil Cabinet of the Prussian king and German Emperor. During the Weimar Republic the building served as part of the Prussian Ministry of State. Between 1922 to 1932 Prussian Minister President Otto Braun of the Social Democrat Party lived and worked here. From 1932 to 1933 the president of the Prussian Council of State (and future West German chancellor) Konrad Adenauer, used this as his apartment whilst serving as a Centre Party politician and chief mayor of Cologne. Upon taking power, this is where Hitler put Ribbentrop's office and the Nazis' liaison office, both under the authority of deputy Führer Rudolf Hess who was made responsible for ensuring that all laws, statutes, regulations, promotions and so forth conformed to Nazi ideology. After 1936 the Nazi leadership moved in and the street façade was simplified, in that the neo-baroque architectural decorations were knocked off. After

the war the building's damage was repaired and the building was used as

a student residence. During the DDR era, the "Hanns Eisler" music college used part of the building. Until 1970 the East German State Secretariat for

Professional Schools was based here, followed by the East German state

publishing house until the demise of the DDR in 1990. When office buildings were needed for the new federal government after the fall of the Wall, the house on Wilhelmstrasse 64 (now renumbered with no. 54) was rebuilt, with remnants of the imperial and Nazi era furnishings were obtained. The post-war attic was reconstructed and modelled on the historical building. Since 2000 the building has been the Berlin office of today's Federal Ministry of Food and Agriculture .

Wilhelmstraße 65: Reichsjustizministerium

Wilhelmstraße 68: Reichsministerium für Wissenschaft, Erziehung und Volksbildung

The Reich Ministry of Science and Public Education in July, 1943 and the site today. After the Nazis came to power Bernhard Rust, Gauleiter of South Hanover-Braunschweig, was appointed provisionally as Prussian Minister of Education. After responsibility for arts affairs had been transferred to the Reich Ministry for Public Enlightenment and Propaganda, Rust was appointed Reich Minister for Science, Education and Public Education on May 1, 1934 and tried to bring the school system into line with Nazi ideology whilst discharging those regarded as politically or racially "undesirable" from scientific and research work. The Prussian Ministry of Culture served as the basis of the newly created Reich Ministry, whose officials also dealt with the affairs of the Reich. At the beginning of 1935, the name of the ministry was adapted accordingly and the authority now operated as the Reich and Prussian Ministry for Science, Education and National Education (Reich Ministry of Education or REM). On October 1, 1938, the reference to Prussia was deleted and the Ministry finally renamed the Reich Ministry for Science, Education and National Education. During the war the building complex was destroyed with the exception of the eastern courtyard wing and parts of the connecting passage to the extension. In August 1945, some of its rooms were set aside for the German Central Authority for Public Education. In October 1949 upon the official creation of the DDR, this became the East German Ministry of Public Education. From 1963 until 1989 the ministry was headed by the wife of East Germany's last Head of State, Margot Honecker. From 1970 until the dissolution of East Germany in 1990 it housed the East German Academy of Educational Science. Today it serves as offices for members of the Bundestag.

Wilhelmstraße 70: Embassy of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland

The Palais Strousberg was designed by August Orth for the railway pioneer Bethel Henry Strousberg. Subsequently the building served as British embassy until its destruction in the Second World War. Today in the growing fears of NSA intrusion, it is the subject of German fears that it serves as Britain’s ‘secret listening post in the heart of Berlin.’

After the decision in 1991 to move the German seat of government from Bonn to Berlin, the British government decided to build a new embassy building at the historic location. An architecture competition was then announced which was won by Michael Wilford & Partners. The groundbreaking ceremony took place on June 29, 1998. The only street side of the building was given a large opening over two floors, which is intended to provide a symbolic light. The turquoise green roof was constructed by Michael Wilford as a Potemkin construction with a sloping roof; the house actually only has a flat roof. The new embassy building was opened on July 18, 2000 by HM Queen Elizabeth II. With the increased terrorist threat after the terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001, the entire embassy area was temporarily closed to public access. Special security controls were later introduced for all visitors. In addition, since 2001, Wilhelmstrasse between Behrenstrasse and Unter den Linden has been completely cordoned off from vehicle traffic. The British embassy building is considered the first privately financed embassy both in Germany and around the world. A German company finances the legation for thirty years with the possibility for an extension. It was discovered in 2013 that a wiretapping system for cellphone, WiFi and other communication data has been operated on the roof since 2000 allowing us to eavesdrop on communications between the Chancellery and the Reichstag.

The British Embassy remains at the same spot as it was during the years of crisis. Photos I took for the site British Imperial Flags. Dr. Lothrop Stoddard in his book Into The Darkness- Nazi Germany Today, published in 1940 during the war, remarked how

[t]he most interesting example of Berlin‟s impassive popular mood was the attitude toward the tightly closed British Embassy which is just around the corner from the Adlon. There it stands, with gilded lions and unicorns upon its portals. I had rather expected that this diplomatic seat of the arch-enemy would attract some attention, especially on a Sunday, when this part of town was thronged with outside visitors. Yet, though I watched closely for some time, I never saw a soul give the building more than a passing glance, much less point to it or demonstrate in any way.

Between Behrenstrasse and Unter den Linden, Wilhelmstrasse has been closed to motorised through traffic since 2003 to protect the British embassy there, especially from car bombs .

Wilhelmstraße 72: Reichsministerium für Ernährung und Landwirtschaf

Originally this was the site of a palace built in 1735 and obtained by King Friedrich Wilhelm III of Prussia and had been the residence of the Hohenzollern princes until the revolution in 1918. The Reich Ministry for Food and Agriculture (RMEL) from 1919 to 1945. It had been bombed during the war, after which the office became the Federal Ministry for Food, Agriculture and Forests under the communist authorities. It was finally demolished in 1962 and remained vacant until the mid 1980s when the East Germans began building high-rise apartment blocks.

The grounds of the former palace were chosen to become part of the Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe (Denkmal für die ermordeten Juden Europas)

Nothing is left of it today, but the Reich Aviation Ministry can be seen in the background.

Nothing is left of it today, but the Reich Aviation Ministry can be seen in the background.

In 1939 the office issued a formal statement about the so-called Jewish question as a factor of foreign policy. Among other things, "[t]he realisation that Judaism in the world will always be the implacable opponent of the Third Reich forces the decision to prevent any strengthening of the Jewish position. A Jewish state [ie: British Palestine] would, however, bring a legal system of international law to world Jewry. " The research results published in October 2010 by the independent historian commission, convened by the then Foreign Minister Joschka Fischer in 2005, show that "after the attack on the Soviet Union in June 1941, the Foreign Office took the initiative to solve the 'Jewish question' at European level. Eckart Conze (historian and spokesman of the commission) said in a 2010 interview that the Foreign Office "was actively involved in all measures of persecution, deprivation, expulsion and extermination of the Jews from the beginning... The target 'final solution' was already very early recognisable." After the war, a number of leading members of the Office in the so-called Wilhelmstraßen process.

Wilhelmplatz

Wilhelmplatz was built over during the German Democratic Republic era. The Czech Embassy is visible in the foreground of the picture whilst the historic statues have since been reinstated.

Wilhelmplatz was built over during the German Democratic Republic era. The Czech Embassy is visible in the foreground of the picture whilst the historic statues have since been reinstated.

Taxis

lined up in front of the legendary Hotel Kaiserhof in 1938 and the same

site today with my students during our Bavarian International School

class trip in 2020. On November 22, 1943 the hotel was badly damaged by

the RAF during an air-raid on Berlin. The ruins ended up in East Berlin

after the division of the city and were later completely torn down and

in 1974 the North Korean embassy to East Germany was constructed on the

site. When in 2001 its successor state, the Federal Republic of Germany,

re-established diplomatic relations with North Korea, the latter's

embassy returned to the building. Since 2004, the annex on the south

half of the site has been leased to Cityhostel Berlin, which currently pays the North Korean regime an estimated €38,000 per month. It was here

on February 26, 1932 in a ceremony that Hitler had himself appointed a

Regierungsrat in Brunswick for the period of a week, thus acquiring

German citizenship. Fest

writes how this was "for years his Berlin headquarters;" Irving adds

that "[t]his was where Hitler made his command post whenever he was in

Berlin." After having lunch "Hitler read newspapers, brought by an aide

each day from a kiosk at the nearby Kaiserhof Hotel. In earlier years he

had taken tea in the Kaiserhof: as he entered, the little orchestra

would strike up the ‘Donkey Serenade,’ his favourite Hollywood movie

tune." On the day Hitler was appointed Chancellor

Taxis

lined up in front of the legendary Hotel Kaiserhof in 1938 and the same

site today with my students during our Bavarian International School

class trip in 2020. On November 22, 1943 the hotel was badly damaged by

the RAF during an air-raid on Berlin. The ruins ended up in East Berlin

after the division of the city and were later completely torn down and

in 1974 the North Korean embassy to East Germany was constructed on the

site. When in 2001 its successor state, the Federal Republic of Germany,

re-established diplomatic relations with North Korea, the latter's

embassy returned to the building. Since 2004, the annex on the south

half of the site has been leased to Cityhostel Berlin, which currently pays the North Korean regime an estimated €38,000 per month. It was here

on February 26, 1932 in a ceremony that Hitler had himself appointed a

Regierungsrat in Brunswick for the period of a week, thus acquiring

German citizenship. Fest

writes how this was "for years his Berlin headquarters;" Irving adds

that "[t]his was where Hitler made his command post whenever he was in

Berlin." After having lunch "Hitler read newspapers, brought by an aide

each day from a kiosk at the nearby Kaiserhof Hotel. In earlier years he

had taken tea in the Kaiserhof: as he entered, the little orchestra

would strike up the ‘Donkey Serenade,’ his favourite Hollywood movie

tune." On the day Hitler was appointed Chancellor

A

few months later Goebbels would give his speech on ‘The Tasks of the

German Theatre’ at the Hotel Kaiserhof on May 8, 1933 during which he

lectured the assembled theatre actors and managers on his concept of a

militant Nazi culture. Irving records him as declaring that "I want to protest at the notion that

the artist alone has the privilege of being unpolitical... The artist may not merely trail behind, he must seize the banner and march at the

head." Turning to the Jewish question, he grimly affirmed that there was

no need for special legislation to extrude the Jews from the world of

German art. "I think the German people will themselves gradually

eliminate them."

Directly across the street is this memorial to Georg Elser, who had concealed a time bomb in the Bürgerbräukeller, set to go off during Hitler's speech on 8 November. The bomb exploded, killing seven people and injuring sixty-three, but Hitler escaped unharmed; he had cut his speech short and left about half an hour early. Elser was arrested, imprisoned for 5 ½ years and executed shortly before the end of the war. On November 8, 2011, this seventeen metre-long memorial was inaugurated on the corner of An der Kolonnade street in his memory.

A

few months later Goebbels would give his speech on ‘The Tasks of the

German Theatre’ at the Hotel Kaiserhof on May 8, 1933 during which he

lectured the assembled theatre actors and managers on his concept of a

militant Nazi culture. Irving records him as declaring that "I want to protest at the notion that

the artist alone has the privilege of being unpolitical... The artist may not merely trail behind, he must seize the banner and march at the

head." Turning to the Jewish question, he grimly affirmed that there was

no need for special legislation to extrude the Jews from the world of

German art. "I think the German people will themselves gradually

eliminate them."

Directly across the street is this memorial to Georg Elser, who had concealed a time bomb in the Bürgerbräukeller, set to go off during Hitler's speech on 8 November. The bomb exploded, killing seven people and injuring sixty-three, but Hitler escaped unharmed; he had cut his speech short and left about half an hour early. Elser was arrested, imprisoned for 5 ½ years and executed shortly before the end of the war. On November 8, 2011, this seventeen metre-long memorial was inaugurated on the corner of An der Kolonnade street in his memory.

Wilhelmplatz 8-9: Reichsministerium für Volksaufklärung und Propaganda

My 2021 cohort in front. The Ministry was created shortly after the Nazi "seizure of power"to serve as the central institution of propaganda through Goebbels, who exercised control over all German mass media and cultural workers through his department and the Reich Chamber of Culture established in autumn 1933. On March 25, 1933, Goebbels explained the future function of the Ministry of Propaganda to the directors and directors of the broadcasting companies by declaring that “[t]he ministry has the task of carrying out a spiritual mobilisation in Germany. So it is in the field of the spirit what the Ministry of Defence is in the field of the guard. [...] the spiritual mobilisation is just as necessary, perhaps even more necessary than the material mobilisation of the people."

My 2021 cohort in front. The Ministry was created shortly after the Nazi "seizure of power"to serve as the central institution of propaganda through Goebbels, who exercised control over all German mass media and cultural workers through his department and the Reich Chamber of Culture established in autumn 1933. On March 25, 1933, Goebbels explained the future function of the Ministry of Propaganda to the directors and directors of the broadcasting companies by declaring that “[t]he ministry has the task of carrying out a spiritual mobilisation in Germany. So it is in the field of the spirit what the Ministry of Defence is in the field of the guard. [...] the spiritual mobilisation is just as necessary, perhaps even more necessary than the material mobilisation of the people." Numerous tasks of the Propaganda Ministry overlapped with the areas of competence of other organisations, which were linked by a complex network of personnel and in some cases were also under the direction of Goebbels. As a professional organisation, the Reich Chamber of Culture controlled and monitored cultural workers in the theatre, radio, film and press, among other areas. At party level, there were also three Reichsleiter with media skills, whose areas of responsibility overlapped: the Reich Propaganda Head of the Nazi Party, Joseph Goebbels; the Reichsleiter for the Nazi Party press, Max Amann; and the Nazi Party Press Chief, Otto Dietrich who was the vice president of the Reich Press Chamber which in turn was subordinate to the President of the Reich Chamber of Culture- Joseph Goebbels. Power struggles, personal enmities and mutual dependencies sometimes led to contradicting instructions from the various agencies. At the 1936 Summer Olympics, direct responsibility lay with the Reich Ministry of the Interior , which was responsible for sport.

Numerous tasks of the Propaganda Ministry overlapped with the areas of competence of other organisations, which were linked by a complex network of personnel and in some cases were also under the direction of Goebbels. As a professional organisation, the Reich Chamber of Culture controlled and monitored cultural workers in the theatre, radio, film and press, among other areas. At party level, there were also three Reichsleiter with media skills, whose areas of responsibility overlapped: the Reich Propaganda Head of the Nazi Party, Joseph Goebbels; the Reichsleiter for the Nazi Party press, Max Amann; and the Nazi Party Press Chief, Otto Dietrich who was the vice president of the Reich Press Chamber which in turn was subordinate to the President of the Reich Chamber of Culture- Joseph Goebbels. Power struggles, personal enmities and mutual dependencies sometimes led to contradicting instructions from the various agencies. At the 1936 Summer Olympics, direct responsibility lay with the Reich Ministry of the Interior , which was responsible for sport.  But since Goebbels had already met with Theodor Lewald, the President of the Organising Committee, he was able to contribute accordingly at all levels. The success of the propaganda is still visible through Leni Riefenstahl's film Olympia. There were violent disputes over who was responsible for foreign propaganda, for which the Reich Foreign Ministry claimed general authority. For example, influencing internal reporting in Italy remained completely in the hands of the Foreign Office; diplomatic sensitivity was required when dealing with the Axis partner. Since regulations and prohibitions were inappropriate in relation to a sovereign state, the Office flooded the Italian Ministry of Propaganda with ready-made news from around the world instead - news that was more detailed and timely than the material of the Italian correspondents, and was therefore often used by newspapers and radio. Although Hitler's order of September 8, 1939 clearly defined the leadership role of the Foreign Office in foreign propaganda, Goebbels and his ministry continued to interfere in this area until the end of the war .

But since Goebbels had already met with Theodor Lewald, the President of the Organising Committee, he was able to contribute accordingly at all levels. The success of the propaganda is still visible through Leni Riefenstahl's film Olympia. There were violent disputes over who was responsible for foreign propaganda, for which the Reich Foreign Ministry claimed general authority. For example, influencing internal reporting in Italy remained completely in the hands of the Foreign Office; diplomatic sensitivity was required when dealing with the Axis partner. Since regulations and prohibitions were inappropriate in relation to a sovereign state, the Office flooded the Italian Ministry of Propaganda with ready-made news from around the world instead - news that was more detailed and timely than the material of the Italian correspondents, and was therefore often used by newspapers and radio. Although Hitler's order of September 8, 1939 clearly defined the leadership role of the Foreign Office in foreign propaganda, Goebbels and his ministry continued to interfere in this area until the end of the war .

The grounds of the former palace were chosen to become part of the Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe (Denkmal für die ermordeten Juden Europas)

Wilhelmstraße 74-76: The Foreign Office

The Foreign Office in 1935 and 1936. Through the Machtergreifung, the personnel policy of the German Foreign Office was subjected to Nazi policy, as was the case with all other Reich ministries. Nevertheless, resistance from the Foreign Service did admittedly emerge, for example Rudolf von Scheli, Ilse Stöbe, Adam von Trott to Solz and Ulrich von Hassell. Nevertheless, in its 2010 report Unabhängige Historikerkommission – Auswärtiges Amt, the "Independent Historical Committee - German Foreign Office" concluded that the Office's employees during the Nazi period were less victims but rather actors of National Socialism:

The Foreign Office was [...] not a hoard of resistance. It was also no retreat of old-ministerial bureaucrats, who, under a bad government, would not abandon their country and simply continue their ministry. There was also no targeted infiltration by national socialists, which was not necessary at all. What was more characteristic of AA was the "self-equalisation. An antidemocratic and an anti-Semitic consensus prevailed among the officials in the Wilhelmstrasse and the Hitler government. The most aristocratic diplomats represented the traditional upper-class anti-Semitism, which was less radical than the genocidal anti-Semitism of the national socialists. But both wanted to overcome the "plague of peace" of Versailles and make Germany a great power again. There were only differences in the assessment of the risk of war.

Nothing is left of it today, but the Reich Aviation Ministry can be seen in the background.

Nothing is left of it today, but the Reich Aviation Ministry can be seen in the background.In 1939 the office issued a formal statement about the so-called Jewish question as a factor of foreign policy. Among other things, "[t]he realisation that Judaism in the world will always be the implacable opponent of the Third Reich forces the decision to prevent any strengthening of the Jewish position. A Jewish state [ie: British Palestine] would, however, bring a legal system of international law to world Jewry. " The research results published in October 2010 by the independent historian commission, convened by the then Foreign Minister Joschka Fischer in 2005, show that "after the attack on the Soviet Union in June 1941, the Foreign Office took the initiative to solve the 'Jewish question' at European level. Eckart Conze (historian and spokesman of the commission) said in a 2010 interview that the Foreign Office "was actively involved in all measures of persecution, deprivation, expulsion and extermination of the Jews from the beginning... The target 'final solution' was already very early recognisable." After the war, a number of leading members of the Office in the so-called Wilhelmstraßen process.

Wilhelmstraße 79-80/Voßstraße 96: Reich Ministry of Transport (Reichsverkehrsministerium)

Then and now as seen from Voßstraße. It had been built in 1884-86 by Boeckmann architects as a residential building. In 1925 the house was extended and fitted to the neighbouring German Railway Company. Today it is the only house of the old Voßstraße still existing. With the founding of the Ministry of Aviation on May 5, 1933, the Reichsverkehrsministerium lost the jurisdiction over the Department of Aviation. The Department of Motor Transport and Shipping was divided into two separate departments as Erich Klausener became head of the shipping division. After Klausener's assassination during the so-called Röhm-Putsch on June 30, 1934, the division received a new department head with Max Waldeck at the beginning of 1935. In the same year, the two railway divisions were merged after the head of the administrative department had retired. As of March 20, 1935, the Reichsverkehrsminister (Minister of Transport and Transport) was named Reich and Prussian Transport Minister after the corresponding tasks had been taken over from the Prussian Ministry of Transport. Added to this were other transport tasks from the Ministry of Economic Affairs and Agriculture. The Reichsbahn-Gesellschaft was placed under the Act for the Reorganisation of the Reichsbank and the German Reichsbahn Act on January 30, 1937, and received the name "Deutsche Reichsbahn". The Reichsbahn committees were taken over to the ministry as department head in the rank of ministerial directors. Until the end of the Second World War the structure changed only insignificantly. In the operational and construction department E II was the unit 21 "mass transport", which from 1940 was responsible for the organisation and timetable of the special trains for the deportation of Jews from Germany ordered by the ϟϟ. This meant that the Reichsverkehrsministerium was responsible for a substantial part of the Holocaust.

Wilhelmplatz

At the western entrance to the subway station "Kaiserhof" at Berlin, Wilhelmplatz (today station "Mohrenstraße", line U2); built 1908 after a design by Alfred Grenander, destroyed in 1936.

For some years a regular daily meeting had taken place in the Propaganda Ministry on the Wilhelmplatz in Berlin, attended by Goebbels, senior officials of the RMVP and liaison and media staff from other ministries, the Party Chancellery and the Wehrmacht. These press conferences would normally begin at 11.am (although the time could vary from 10.00 am to noon) and lasted for half an hour to forty-five minutes. Goebbels dominated proceedings and the only other regular speaker was the OKW liaison officer who would give a brief account of developments at the front(s). The ministerial conference was very much a platform for Goebbels to perform. The Minister would use the 'conference’ to provide guidelines and detailed instructions for the implementation of German propaganda. It was not intended to offer a dialogue with journalists. As Goebbels widened the scope of his brief during the war the conference expanded from twenty in attendance gradually increasing after the invasion of Russia to fifty or sixty persons.

Welch (118) The Third Reich: Politics and Propaganda

A member of the Hitlerjugend on a street sign where Wilhelmstrasse intersects with Wilhelmplatz, and as it appeared after the war.

Taxis

lined up in front of the legendary Hotel Kaiserhof in 1938 and the same

site today with my students during our Bavarian International School

class trip in 2020. On November 22, 1943 the hotel was badly damaged by

the RAF during an air-raid on Berlin. The ruins ended up in East Berlin

after the division of the city and were later completely torn down and

in 1974 the North Korean embassy to East Germany was constructed on the

site. When in 2001 its successor state, the Federal Republic of Germany,

re-established diplomatic relations with North Korea, the latter's

embassy returned to the building. Since 2004, the annex on the south

half of the site has been leased to Cityhostel Berlin, which currently pays the North Korean regime an estimated €38,000 per month. It was here

on February 26, 1932 in a ceremony that Hitler had himself appointed a

Regierungsrat in Brunswick for the period of a week, thus acquiring

German citizenship. Fest

writes how this was "for years his Berlin headquarters;" Irving adds

that "[t]his was where Hitler made his command post whenever he was in

Berlin." After having lunch "Hitler read newspapers, brought by an aide

each day from a kiosk at the nearby Kaiserhof Hotel. In earlier years he

had taken tea in the Kaiserhof: as he entered, the little orchestra

would strike up the ‘Donkey Serenade,’ his favourite Hollywood movie

tune." On the day Hitler was appointed Chancellor

Taxis

lined up in front of the legendary Hotel Kaiserhof in 1938 and the same

site today with my students during our Bavarian International School

class trip in 2020. On November 22, 1943 the hotel was badly damaged by

the RAF during an air-raid on Berlin. The ruins ended up in East Berlin

after the division of the city and were later completely torn down and

in 1974 the North Korean embassy to East Germany was constructed on the

site. When in 2001 its successor state, the Federal Republic of Germany,

re-established diplomatic relations with North Korea, the latter's

embassy returned to the building. Since 2004, the annex on the south

half of the site has been leased to Cityhostel Berlin, which currently pays the North Korean regime an estimated €38,000 per month. It was here

on February 26, 1932 in a ceremony that Hitler had himself appointed a

Regierungsrat in Brunswick for the period of a week, thus acquiring

German citizenship. Fest

writes how this was "for years his Berlin headquarters;" Irving adds

that "[t]his was where Hitler made his command post whenever he was in

Berlin." After having lunch "Hitler read newspapers, brought by an aide

each day from a kiosk at the nearby Kaiserhof Hotel. In earlier years he

had taken tea in the Kaiserhof: as he entered, the little orchestra

would strike up the ‘Donkey Serenade,’ his favourite Hollywood movie

tune." On the day Hitler was appointed Chancellor at a window of the Kaiserhof, Rohm was keeping an anxious watch on the door from which Hitler must emerge. Shortly after noon a roar went up from the crowd: the Leader was coming. He ran down the steps to his car and in a couple of minutes was back in the Kaiserhof, As he entered the room his lieutenants crowded to greet him. The improbable had happened: Adolf Hitler, the petty official's son from Austria, the down-and-out of the Home for Men, the Meldeganger of the List Regiment, had become Chancellor of the German Reich.Bullock (250).

A

few months later Goebbels would give his speech on ‘The Tasks of the

German Theatre’ at the Hotel Kaiserhof on May 8, 1933 during which he

lectured the assembled theatre actors and managers on his concept of a

militant Nazi culture. Irving records him as declaring that "I want to protest at the notion that

the artist alone has the privilege of being unpolitical... The artist may not merely trail behind, he must seize the banner and march at the

head." Turning to the Jewish question, he grimly affirmed that there was

no need for special legislation to extrude the Jews from the world of

German art. "I think the German people will themselves gradually

eliminate them."

A

few months later Goebbels would give his speech on ‘The Tasks of the

German Theatre’ at the Hotel Kaiserhof on May 8, 1933 during which he

lectured the assembled theatre actors and managers on his concept of a

militant Nazi culture. Irving records him as declaring that "I want to protest at the notion that

the artist alone has the privilege of being unpolitical... The artist may not merely trail behind, he must seize the banner and march at the

head." Turning to the Jewish question, he grimly affirmed that there was

no need for special legislation to extrude the Jews from the world of

German art. "I think the German people will themselves gradually

eliminate them."

The bronze statue of Leopold I shown with my students during my 2016 Bavarian International School trip was moved in 2005

to its current location on Wilhelmplatz on the initative of the Berlin

Schadow Society which planned to re-erect the statues of the Prussian

military near their historical locations. The bronze copies of the

Zieten and Anhalt-Dessau monuments were rebuilt in 2003 and 2005 on the

subway island on the transverse axis of the former Wilhelmplatz. The

remaining four bronze statues were moved to a new location on the

neighboring Zietenplatz in September 2009 after its reconstruction,

which began in 2005, was completed. Since 2011, the statues as a whole

have been a listed building.

The NSDAP leader was often in Berlin, where since February 1931 he regularly stayed in a suite at the legendary Hotel Kaiserhof at 4 Wilhelmplatz (formerly Ziethenplatz), across the street from the Reich Chancellery. The hotel was the first luxury hotel in the city, opened in 1875 and three years later one of the showpieces of the 1878 Congress of Berlin, which took place under the leadership of Chancellor Otto von Bismarck. Since the early 1920s, the hotel management had sympathized with the right‑wing nationalist forces operating against the Weimar state, so it was no coincidence that the top floor of the hotel turned into the NSDAP’s provisional headquarters.

Wilhelmplatz 8-9: Reichsministerium für Volksaufklärung und Propaganda

A Berlin postcard actually promoting the site of Goebbels's Propaganda Ministry and my class of 2021. Shortly after the Reichstag election in March 1933, Hitler presented his cabinet on March 11 with a draft resolution for the establishment of the ministry. Despite the skepticism of some non-Nazi ministers, he prevailed. On March 13, 1933, the Reich President Hindenburg ordered the establishment of a Reich Ministry for Public Enlightenment and Propaganda. The term “propaganda” (from Latin propagare , “further spread”) was used in a value-neutral manner at the time of its founding. The meaning of the ministry name can be understood today in the sense of "for culture, media and public relations", whereby the boundary between advertising and public relations was already fluid which Goebbels tried to differentiate. The ministry moved here into the Prinz-Karl-Palais on Wilhelmplatz 8/9 in Berlin, which was already used by the now incorporated "United Press Department of the Reich Government". From the spring of 1933, the complex was expanded extensively. Due

to the insufficient space there, architect Karl Reichle created

spacious extensions between 1934 and 1938. The rear façade of the extant

new wing on Mauerstrasse offers a good impression of Nazi state

architecture: Conservative modernism and monumental austerity are

reflected in the shell limestone façade with its uniform serial pattern.

My 2021 cohort in front. The Ministry was created shortly after the Nazi "seizure of power"to serve as the central institution of propaganda through Goebbels, who exercised control over all German mass media and cultural workers through his department and the Reich Chamber of Culture established in autumn 1933. On March 25, 1933, Goebbels explained the future function of the Ministry of Propaganda to the directors and directors of the broadcasting companies by declaring that “[t]he ministry has the task of carrying out a spiritual mobilisation in Germany. So it is in the field of the spirit what the Ministry of Defence is in the field of the guard. [...] the spiritual mobilisation is just as necessary, perhaps even more necessary than the material mobilisation of the people."

My 2021 cohort in front. The Ministry was created shortly after the Nazi "seizure of power"to serve as the central institution of propaganda through Goebbels, who exercised control over all German mass media and cultural workers through his department and the Reich Chamber of Culture established in autumn 1933. On March 25, 1933, Goebbels explained the future function of the Ministry of Propaganda to the directors and directors of the broadcasting companies by declaring that “[t]he ministry has the task of carrying out a spiritual mobilisation in Germany. So it is in the field of the spirit what the Ministry of Defence is in the field of the guard. [...] the spiritual mobilisation is just as necessary, perhaps even more necessary than the material mobilisation of the people."From the spring of 1933, the complex was expanded extensively. The neighbouring American embassy in the Kleisthaus was built into the building. The tasks of the ministry are described in an ordinance by Hitler of June 30, 1933 as follows:"The Reich Minister for Public Enlightenment and Propaganda is responsible for all tasks of intellectual influence on the nation, advertising for the state, culture and economy, informing the domestic and foreign public about them and the administration of all institutions serving these purposes."

Numerous tasks of the Propaganda Ministry overlapped with the areas of competence of other organisations, which were linked by a complex network of personnel and in some cases were also under the direction of Goebbels. As a professional organisation, the Reich Chamber of Culture controlled and monitored cultural workers in the theatre, radio, film and press, among other areas. At party level, there were also three Reichsleiter with media skills, whose areas of responsibility overlapped: the Reich Propaganda Head of the Nazi Party, Joseph Goebbels; the Reichsleiter for the Nazi Party press, Max Amann; and the Nazi Party Press Chief, Otto Dietrich who was the vice president of the Reich Press Chamber which in turn was subordinate to the President of the Reich Chamber of Culture- Joseph Goebbels. Power struggles, personal enmities and mutual dependencies sometimes led to contradicting instructions from the various agencies. At the 1936 Summer Olympics, direct responsibility lay with the Reich Ministry of the Interior , which was responsible for sport.

Numerous tasks of the Propaganda Ministry overlapped with the areas of competence of other organisations, which were linked by a complex network of personnel and in some cases were also under the direction of Goebbels. As a professional organisation, the Reich Chamber of Culture controlled and monitored cultural workers in the theatre, radio, film and press, among other areas. At party level, there were also three Reichsleiter with media skills, whose areas of responsibility overlapped: the Reich Propaganda Head of the Nazi Party, Joseph Goebbels; the Reichsleiter for the Nazi Party press, Max Amann; and the Nazi Party Press Chief, Otto Dietrich who was the vice president of the Reich Press Chamber which in turn was subordinate to the President of the Reich Chamber of Culture- Joseph Goebbels. Power struggles, personal enmities and mutual dependencies sometimes led to contradicting instructions from the various agencies. At the 1936 Summer Olympics, direct responsibility lay with the Reich Ministry of the Interior , which was responsible for sport.  But since Goebbels had already met with Theodor Lewald, the President of the Organising Committee, he was able to contribute accordingly at all levels. The success of the propaganda is still visible through Leni Riefenstahl's film Olympia. There were violent disputes over who was responsible for foreign propaganda, for which the Reich Foreign Ministry claimed general authority. For example, influencing internal reporting in Italy remained completely in the hands of the Foreign Office; diplomatic sensitivity was required when dealing with the Axis partner. Since regulations and prohibitions were inappropriate in relation to a sovereign state, the Office flooded the Italian Ministry of Propaganda with ready-made news from around the world instead - news that was more detailed and timely than the material of the Italian correspondents, and was therefore often used by newspapers and radio. Although Hitler's order of September 8, 1939 clearly defined the leadership role of the Foreign Office in foreign propaganda, Goebbels and his ministry continued to interfere in this area until the end of the war .

But since Goebbels had already met with Theodor Lewald, the President of the Organising Committee, he was able to contribute accordingly at all levels. The success of the propaganda is still visible through Leni Riefenstahl's film Olympia. There were violent disputes over who was responsible for foreign propaganda, for which the Reich Foreign Ministry claimed general authority. For example, influencing internal reporting in Italy remained completely in the hands of the Foreign Office; diplomatic sensitivity was required when dealing with the Axis partner. Since regulations and prohibitions were inappropriate in relation to a sovereign state, the Office flooded the Italian Ministry of Propaganda with ready-made news from around the world instead - news that was more detailed and timely than the material of the Italian correspondents, and was therefore often used by newspapers and radio. Although Hitler's order of September 8, 1939 clearly defined the leadership role of the Foreign Office in foreign propaganda, Goebbels and his ministry continued to interfere in this area until the end of the war . The Ministry for Popular Enlightenment and Propaganda (Reichsministerium für Volksaufklärung und Propaganda – RMVP), was established by a presidential decree, signed on 12 March 1933 and promulgated on the following day, which defined the task of the new ministry as the dissemination of ‘enlightenment and propaganda within the population concerning the policy of the Reich Government and the national reconstruction of the German Fatherland’. In June Hitler was to define the scope of the RMVP in even more general terms, making Goebbels responsible for the ‘spiritual direction of the nation’. Not only did this vague directive provide Goebbels with room to out-manoeuvre his critics within the Party; it also put the seal of legitimacy on what was soon to be the ministry’s wholesale control of the mass-media. Nevertheless, Goebbels was constantly involved in quarrels with ministerial colleagues who resented the encroachment of this new ministry on their old domain.

Welch (28-29) The Third Reich: Politics and Propaganda

Standing in front of the site in 2007. Currently serving as the German Federal Ministry of Health and Social Security, this is where Goebbels was in charge of the

Reich Ministry for Public Enlightenment and Propaganda (RMVP) was

responsible for the content-related control of the press, literature,

fine arts, film, theatre, music and broadcasting. After the first ministerial building here was destroyed in the war, a remnant marked by archways remained standing on Wilhelmstrasse.

The part of the building visible here behind my students is the Marschall House, converted by Karl Reichle in 1934 to serve as the entrance area to the Ministry of Propaganda. The walled up archways and windows of today were originally passageways to the main building of the Ministry of Propaganda. The ministry was re-established shortly after the "seizure of power" by the Nazis as the central institution of Nazi propaganda. It was in the Cabinet Hitler under the direction of Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels, who exerted control of all German mass media and cultural workers through his ministry and the Reich Chamber of Culture built in the fall of 1933.

No one who lived in Germany in the Thirties, and who cared about such matters, can ever forget the sickening decline of the cultural standards of a people who had had such high ones for so long a time. This was inevitable, of course, the moment the Nazi leaders decided that the arts, literature, the press, radio and the films must serve exclusively the propaganda purposes of the new regime and its outlandish philosophy.

Not a single living German writer of any importance, with the exception of Ernst Juenger and Ernst Wiechert in the earlier years, was published in Germany during the Nazi time. Almost all of them, led by Thomas Mann, emigrated; the few who remained were silent or were silenced. Every manuscript of a book or a play had to be submitted to the Propaganda Ministry before it could be approved for publication or production.

Shirer (214)

In the last weeks of the war, the historic palace was destroyed by an air mine. Its ruins were torn down in 1949 whilst the parts of the building that were built during the Nazi regime were damaged but reconstructed after the war. From 1947 the National Front of the German Democratic Republic, an association of parties and mass organisations of the DDR, moved into this building. With the move of the Ministry for Media Policy into the building of the former Propaganda Ministry, the East German government ensured continuity in the use of the building. Since 1999 the building has been the seat of the Federal Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs.

Wilhelmstraße 81-85: Reich Aviation Ministry (Reichsluftfahrtministerium)

As it appeared in the film Valkyrie and during my 2021 school trip with my Bavarian International School history students. The building also provided the backdrop to the dire 2007 film Mein Führer - Die wirklich wahrste Wahrheit über Adolf Hitler (Mein Führer: The Truly Truest Truth About Adolf Hitler).In 1890 Das Preussische Kriegsministerium at Leipzigerstrasse 5 was enlarged by the construction of an huge extension in Wilhelmstrasse.  During the Weimar Republic it contained the offices of the Reich Defence Ministry. In 1933 the newly-formed Reich Aviation Ministry headed by Goering moved into it, at which point he ordered the complex destroyed and a monumental new building designed by Ernst Sagebiel constructed on the site, housing 2000 rooms.

During the Weimar Republic it contained the offices of the Reich Defence Ministry. In 1933 the newly-formed Reich Aviation Ministry headed by Goering moved into it, at which point he ordered the complex destroyed and a monumental new building designed by Ernst Sagebiel constructed on the site, housing 2000 rooms.

During the Weimar Republic it contained the offices of the Reich Defence Ministry. In 1933 the newly-formed Reich Aviation Ministry headed by Goering moved into it, at which point he ordered the complex destroyed and a monumental new building designed by Ernst Sagebiel constructed on the site, housing 2000 rooms.

During the Weimar Republic it contained the offices of the Reich Defence Ministry. In 1933 the newly-formed Reich Aviation Ministry headed by Goering moved into it, at which point he ordered the complex destroyed and a monumental new building designed by Ernst Sagebiel constructed on the site, housing 2000 rooms.

During its construction in 1935, as shown in the 1936 series of Winterhilfswerk Moderne Bauten stamps on the left and from my guided tour of various sites, including the Reichsluftfahrtministerium.

Historians have devoted considerable attention to Hitler’s plans for the rebuilding of Berlin, but they have rarely acknowledged their effect on both the face of tourist Berlin and the meaning of a visit to the capital between 1933 and 1945. Yet it is impossible to overestimate the degree to which Berlin’s new buildings – among them, the Reich Chancellery, the Reich Sport Field, the Reich Ministry of Transportation and the Reich Aviation Ministry – became key sights for visitors to the city.

Seeing Hitler's Germany: Tourism in the Third Reich Kristin Semmens (46)

In May 1933, the newly founded Reich Aviation Ministry took over the entire building complex at the corner of Leipziger Strasse Wilhelmstrasse, which had been the seat of the Prussian War Ministry until 1918 and, in the Weimar Republic, the seat of the Reichswehr Ministry and the Ministry of Labour.

In May 1933, the newly founded Reich Aviation Ministry took over the entire building complex at the corner of Leipziger Strasse Wilhelmstrasse, which had been the seat of the Prussian War Ministry until 1918 and, in the Weimar Republic, the seat of the Reichswehr Ministry and the Ministry of Labour. On February 2, 1933, the Ordinance on the Reichskommissar for Aviation was issued, ordering a Reichskommissar for the aviation ministry. This was a first step towards establishing an air force. In addition to the army and the navy, it would become a part of the Reichswehr. The Reichskommissar for aviation was responsible for the planning and development of aviation, directly subordinate to the Reichskanzler. To this end, he received from the Reich Ministry of Transportation and the Reich Ministry of the Interior power over all civilian aviation and air defence. To serve as Reichskommissar Hitler appointed the Jagdflieger of the First World War, Nazi politician and Prussian Minister of the Interior Hermann Goering. In January 1935, Goering laid the cornerstone of the new Air Ministry. It would occupy a four-hundred-thousand-square-foot site off the Leipziger Strasse. Hitler personally checked each façade in plaster miniature. Its central longitudinal block and side wings would house four thousand bureaucrats and officers in its twenty-eight hundred rooms. Throughout 1935 the country’s finest architects and sculptors chiselled at heroic reliefs with motifs like “Flag Company,” designed by Professor Arnold Waldschmidt of the Prussian Academy of Fine Arts. The Berliners made smug comments about this extravagance- “Pure and simple, and hang the expense!” was one; “Just humble gold” was another.

David Irving, Göring (216-7)

The Main Hall (Ehrensaal) inside then and now. Three days after Reichskristallnacht in November 1938, Goering held a conference here (now the Euro Hall) wherein it was resolved that a thousand million Reichsmarks would be demanded from German Jews to pay for the damage caused by the pogrom.

“The swine will think twice,” he said, “before they inflict a second murder on us.” But the unthinking and needlessly destructive mode of revenge that Goebbels had selected outraged him. As his limousine made its way through the shards in Berlin the next morning, November 10 he got fighting mad and called a terse meeting of the Nazi party leaders at the Air Ministry building. Walther Darré heard Göring call the pogrom “a bloody outrage.” The field marshal lectured them all on their “lack of discipline.” He reserved his most pained language for Dr. Joseph Goebbels. “I buy most of my works of art from Jewish dealers,” he cried. Goebbels rushed yelping to the Führer’s lunch table but found little sympathy. Hitler had spent the night in Munich issuing orders to stop the outrages and sending out his adjutants to protect Jewish businesses like Bernheimer’s, the antique dealers. Himmler was also furious with Goebbels for having made free with the local SS units to stage the pogrom.

Irving (341)

The building from the Nazi-era and in 2007. The Reich Aviation Ministry remains the only major surviving public building in the Wilhelmstrasse from the Nazi era at Wilhelmstraße 81-85, south of the Leipziger Strasse, a huge edifice built on the orders of Hermann Göring between 1933 and 1936 based on a design by Ernst Sagebiel, who shortly afterwards rebuilt Tempelhof Airport on a similarly gigantic scale. One writer has described it as "in the typical style of National Socialist intimidation architecture." It ran for more than 250 metres along Wilhelmstraße, partly on the site of the former Prussian War Ministry that had dated from 1819, and covered the full length of the block between Prinz-Albrecht-Straße and Leipziger Straße, even running along Leipziger Straße itself to join on to the Prussian Herrenhaus, the former Upper House of the Prussian Parliament. It comprised of a reinforced concrete skeleton with an exterior facing of limestone and travertine (a form of marble). In 1935 all the buildings in the area were demolished and the area expanded through acquisitions up to Prinz-Albrecht-Straße in the south. The gigantic new building with its usable area of 56,000 square metres and 2,100 interior rooms was completed at the end of 1936. A labyrinth of corridors with a total length of 6.8 kilometres established the connections in this gigantic ensemble.

The Reich Aviation Ministry was the first large new building of the new Nazi government. The architect in charge, Prof. Ernst Sagebiel, implemented what Göring demanded when, in his speech on October 12, 1935, Göring said on the inauguration of the new building, he declared that "[w]e are taking over a good piece of Prussian-German tradition from it." Sagebiel had relief panels with German military leaders attached as façade decorations, but these took a back seat to the actual decoration with swastikas, military symbols such as the Iron Cross and the Pour le Mérite, the highest German order of merit. Göring, a fighter pilot in the First World War, had been the bearer of the Pour le Mérite. Here on the left I stand beside one of the entrances and as it appeared when the offending symbols were removed after the war and subsequently replaced with cladding.

Under the Versailles Treaty of June 28, 1919, Germany had

been forbidden to rebuild its air forces and its civil aviation was severely

hindered. The new regime quickly broke this treaty, first in secret, then

publicly with the occupation of the Rhineland in March 1936 and the

attack by the Condor Legion on

the Basque city of Guernica in April 1937.

With its seven storeys and total floor area of 112,000 square metres, 2,800 rooms, seven kilometres of corridors, over four thousand windows, seventeen stairways, and with the stone coming from no fewer than fifty quarries, the vast building served the growing bureaucracy of the Luftwaffe, plus Germany’s civil aviation authority which was also located there. Yet it took only eighteen months to build, the army of labourers working double shifts and Sundays.  The short construction period of the Reich Aviation Ministry was touted to the public as a "performance show" of the new system. The building complex, built partly as a reinforced concrete, partly as a steel frame structure in a functional aesthetic around several large inner courtyards, enjoyed homogeneous rows of narrow and sharp-edged windows in a strict style overlooking the smooth shell limestone facade. The first thousand rooms were handed over in October 1935 after just eight months' construction. When it had been finally completed, four thousand bureaucrats and their secretaries were employed within its walls. According to Elke Dietrich, “[t]he discipline of the national community is expressed in the discipline of architecture in this building.” In this way, Göring legitimised the New Objectivity style, the application of which until then was described by the Nazis as culturally Bolshevik and soulless; “un-German”.

The short construction period of the Reich Aviation Ministry was touted to the public as a "performance show" of the new system. The building complex, built partly as a reinforced concrete, partly as a steel frame structure in a functional aesthetic around several large inner courtyards, enjoyed homogeneous rows of narrow and sharp-edged windows in a strict style overlooking the smooth shell limestone facade. The first thousand rooms were handed over in October 1935 after just eight months' construction. When it had been finally completed, four thousand bureaucrats and their secretaries were employed within its walls. According to Elke Dietrich, “[t]he discipline of the national community is expressed in the discipline of architecture in this building.” In this way, Göring legitimised the New Objectivity style, the application of which until then was described by the Nazis as culturally Bolshevik and soulless; “un-German”.

The short construction period of the Reich Aviation Ministry was touted to the public as a "performance show" of the new system. The building complex, built partly as a reinforced concrete, partly as a steel frame structure in a functional aesthetic around several large inner courtyards, enjoyed homogeneous rows of narrow and sharp-edged windows in a strict style overlooking the smooth shell limestone facade. The first thousand rooms were handed over in October 1935 after just eight months' construction. When it had been finally completed, four thousand bureaucrats and their secretaries were employed within its walls. According to Elke Dietrich, “[t]he discipline of the national community is expressed in the discipline of architecture in this building.” In this way, Göring legitimised the New Objectivity style, the application of which until then was described by the Nazis as culturally Bolshevik and soulless; “un-German”.

The short construction period of the Reich Aviation Ministry was touted to the public as a "performance show" of the new system. The building complex, built partly as a reinforced concrete, partly as a steel frame structure in a functional aesthetic around several large inner courtyards, enjoyed homogeneous rows of narrow and sharp-edged windows in a strict style overlooking the smooth shell limestone facade. The first thousand rooms were handed over in October 1935 after just eight months' construction. When it had been finally completed, four thousand bureaucrats and their secretaries were employed within its walls. According to Elke Dietrich, “[t]he discipline of the national community is expressed in the discipline of architecture in this building.” In this way, Göring legitimised the New Objectivity style, the application of which until then was described by the Nazis as culturally Bolshevik and soulless; “un-German”.The

enormous building stretches south and west from the corner of Leipziger

Strasse and Wilhelmstrasse, at the southern edge of the traditional

government quarter. Several sprawling wings, ranging from four to seven

stories high, contain two thousand rooms, among them grand halls in

which Reich Marshal Göring received, entertained, and overawed visitors.

Like Sagebiel's airport, its external appearance is modern in its stark

and massive façades but traditional in its stone construction and

monumental entrance courts. A Third Reich guidebook pronounced it a

"document in stone displaying the reawakened military will and the

reestablished military readiness of the new Germany."

Hitler at the site in 1935 at the main entrance of the Reich Aviation Ministry with its forecourt is on Leipziger Strasse and my 2018 cohort. The Ehrenhof faces Wilhelmstrasse as a parade area, the entrance to which was framed by two Nazi eagles, each holding a laurel wreath with a swastika in their claws. Two inner courtyards laid out with large-format granite slabs with framed lawns and two chestnuts each, a utility courtyard and two garden courtyards with sculptures on the lawns forming the exterior of the gigantic building complex. The lobby inside was adorned with a 25 metre-long stone relief by Arno Waldschmidt glorifying the Wehrmacht entitled “Fahnenkompanie.” In June 1943 Waldschmidt received the Goethe Medal for Art and Science with express reference to this relief. Waldschmidt “was also the first to bring the Führer’s ideas into the arts”.

This

building escaped major damage during the war and its large size and intact state in contrast to the rest of Wilhelmstrasse made the building attractive to the new East German government. A dozen ministries were given office space there, and it was renamed the "House of Ministries," which it remained until 1990. As one of the few intact

government buildings in central Berlin, it ended up being occupied by

the Council of Ministers of the new German Democratic Republic in 1949 which had been founded on October 7, 1949, in the great hall of the former Reich Aviation Ministry, and the building complex became the “House of Ministries”. On October 11th the People's Chamber, together with the Länderkammer, 'elected' Wilhelm Pieck as the first and only President of the DDR with Otto Grotewohl becoming Prime Minister. Here the specialist ministries of the various branches of industry are grouped together; In 1953 there are nine government offices and ministries; by 1989 there were sixteen. The East Germans didn't use the building complex without reflecting on its historical origin and declared its use as a symbol of a new beginning with old, negative history being overwritten by the new one that was now emerging here. According to Willi Stoph at the time, “[t]hrough the initiative of the Communist Party of Germany and in accordance with the decision of the Soviet Military Administration, this building was to be given a new purpose... From now on, people should work in the hundreds of workrooms who work for peaceful construction and for life and who do their part to overcome the serious consequences of the predatory Nazi war in our country."

This

building escaped major damage during the war and its large size and intact state in contrast to the rest of Wilhelmstrasse made the building attractive to the new East German government. A dozen ministries were given office space there, and it was renamed the "House of Ministries," which it remained until 1990. As one of the few intact

government buildings in central Berlin, it ended up being occupied by