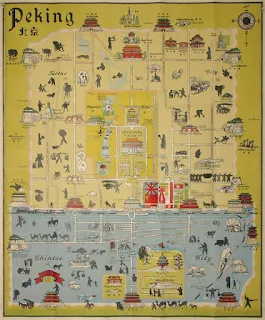

As conceived for the film 55 Days At Peking (1963)

The British Legation- then and now, serving as the Ministry of State Security. Here the majority of besieged diplomats, families and Chinese sheltered during the attacks against them by the Chinese state.

The remains of the Russian Legation, being destroyed as I last visited to pick up relics

US marines in front of the Tartar Wall with the Chien Men tower on the right, one of the gates into the Legation Quarter

The Qianmen gate after the siege. First built in 1419 during the Ming dynasty, it once consisted of the gatehouse proper and an archery tower, which were connected by side walls and together with side gates, formed a large barbican. The gate guarded the direct entry into the imperial city. The city's first railway station, known as the Qianmen Station, was built just outside the gate. During the Boxer Rebellion the gate sustained considerable damage when the Eight-Nation Alliance invaded the city. The Hui and Dongxiang Muslim Kansu Braves under Ma Fulu engaged in fierce fighting during the Battle of Peking at Zhengyangmen against the Eight-Nation Alliance. Ma Fulu and an hundred of his fellow Hui and Dongxiang soldiers from his home village died in that battle. Ma Fulu's cousins, Ma Fugui (馬福貴) and Ma Fuquan (馬福全), and his nephews, Ma Yaotu (馬耀圖) and Ma Zhaotu (馬兆圖), died in the battle. The Battle at Zhengyang was fought against the British who of course won. The Qing Empire later blatantly violated the Boxer Protocol by having a tower constructed at the gate.

The Qianmen gate after the siege. First built in 1419 during the Ming dynasty, it once consisted of the gatehouse proper and an archery tower, which were connected by side walls and together with side gates, formed a large barbican. The gate guarded the direct entry into the imperial city. The city's first railway station, known as the Qianmen Station, was built just outside the gate. During the Boxer Rebellion the gate sustained considerable damage when the Eight-Nation Alliance invaded the city. The Hui and Dongxiang Muslim Kansu Braves under Ma Fulu engaged in fierce fighting during the Battle of Peking at Zhengyangmen against the Eight-Nation Alliance. Ma Fulu and an hundred of his fellow Hui and Dongxiang soldiers from his home village died in that battle. Ma Fulu's cousins, Ma Fugui (馬福貴) and Ma Fuquan (馬福全), and his nephews, Ma Yaotu (馬耀圖) and Ma Zhaotu (馬兆圖), died in the battle. The Battle at Zhengyang was fought against the British who of course won. The Qing Empire later blatantly violated the Boxer Protocol by having a tower constructed at the gate.

The Japanese Legation, the Chinese flag defiantly flying above the current headquarters of the Beijing Municipal Government...

... and when the rising sun flew over

Part of what had served as the Japanese legation

The former Yokohama Specie Bank

The French post office

The former National City Bank of New York, now the Beijing Police Museum

The former National City Bank of New York

St.

Michael's Church (also known as Dongjiaomin Catholic Church) was built

during 1902 on the site of a church destroyed during the Boxer Rebellion

The Former Chartered Bank of India, Australia and China with its foundation date

The Summer Palace circa 1850 and now

Tiananmen during the May Fourth Movement and now

During the 1937 Marco Polo Bridge Incident in Lugouqiao outside Peking in Wanping

Chinese troops in Wanping and the east gate of the Wanping Fortress today and what was left of it after the Marco Polo incident. The fortress, 宛平城 is located at the eastern end of Marco Polo Bridge; the Museum of the Chinese People's War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression is located within its walls with a sculpture park outside of it decorated with numerous sculptures from the Kangxi Emperor's stelae to hundreds of stone barrels by Cai Xueshi inscribed with the list of crimes the Japanese inflicted upon the Chinese people.

Outside the so-called Memorial Hall of the Chinese People's War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression inside Wanping Fortress

The Great Wall from an 1887 set of engravings based on photographs taken by a soldier of Sir Frederick Bruce's Bodyguard

Chiang Kai-shek above the Tian'anmen Rostrum, replaced now for the time being, by Mao

In front of the Lingendian (Hall of Prominent Favour) at Changling in an 1871 photograph by John Thomson. This, the tomb of the Yongle Emperor, is the largest and oldest of the thirteen Ming tombs and oldest of the Ming tombs near Peking and took eighteen years to complete. The columns and pillars are made of Chinese cedar believed to have come all the way from Nepal.

Tibet

The

British army entering Lhasa during the 1904 Younghusband Mission with

me holding Chinese occupation money, showing how the city has suffered

since.

A closer look at the bill shows how much the regime needs to falsify the actual appearance

The Potala Palace from the time of the 1938-1939 German Expedition to Tibet, a German scientific expedition from May 1938 to August 1939, led by German zoologist and ϟϟ officer Ernst Schäfer. Reichsführer-ϟϟ Himmler was attempting to avail himself of the reputation of Ernst Schäfer for Nazi propaganda and asked about his future plans. Ernst Schäfer responded he wanted to lead another expedition to Tibet. Ernst Schäfer wished his expedition to be under the patronage of the cultural department of the foreign affairs or of the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft ("German Research Foundation") as indicated by his requests. Himmler was fascinated by Asian mysticism and therefore wished to send such an expedition under the auspices of the ϟϟ Ahnenerbe (ϟϟ Ancestral Heritage Society), and desired that Schäfer perform research based on Hanns Hörbiger’s pseudo-scientific theory of "Glacial Cosmogony" promoted by the Ahnenerbe. Schäfer had scientific objectives, and he therefore refused to include Edmund Kiss, an adept of this theory, in his team, and requested 12 conditions to obtain scientific freedom. Wolfram Sievers from the Ahnenerbe therefore expressed criticism concerning the objectives of the expedition, so that Ahnenerbe would not sponsor it. Himmler accepted the expedition to be organized on the condition that all its members become ϟϟ. In order to succeed in his expedition, Schäfer had to compromise.

The Potala Palace from the time of the 1938-1939 German Expedition to Tibet, a German scientific expedition from May 1938 to August 1939, led by German zoologist and ϟϟ officer Ernst Schäfer. Reichsführer-ϟϟ Himmler was attempting to avail himself of the reputation of Ernst Schäfer for Nazi propaganda and asked about his future plans. Ernst Schäfer responded he wanted to lead another expedition to Tibet. Ernst Schäfer wished his expedition to be under the patronage of the cultural department of the foreign affairs or of the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft ("German Research Foundation") as indicated by his requests. Himmler was fascinated by Asian mysticism and therefore wished to send such an expedition under the auspices of the ϟϟ Ahnenerbe (ϟϟ Ancestral Heritage Society), and desired that Schäfer perform research based on Hanns Hörbiger’s pseudo-scientific theory of "Glacial Cosmogony" promoted by the Ahnenerbe. Schäfer had scientific objectives, and he therefore refused to include Edmund Kiss, an adept of this theory, in his team, and requested 12 conditions to obtain scientific freedom. Wolfram Sievers from the Ahnenerbe therefore expressed criticism concerning the objectives of the expedition, so that Ahnenerbe would not sponsor it. Himmler accepted the expedition to be organized on the condition that all its members become ϟϟ. In order to succeed in his expedition, Schäfer had to compromise.Gyantse 1904: The British Liberation of Tibet

Finally.

The complete legendary remastered print has been released after seven

long years. Here it is in nearly all its glory; or at least the bits

involving the greatest Empire ever shown on TV. Gyantse 1904- The

British Liberation of Tibet. Originally a television drama directed by Luo Deng for CCTV in 2005 and written by Liu Wei, Li Yaping and Lei Xiaobao, the film was presented by the television station in its online publicity in its usual histrionic terms. (http://www.cctv.com/movie/ 20050831/100294.shtml). Jiangzi 1904 does indeed have all the elements described in the publicity – heroes, mountains, landscapes, snow, battles, bloodshed, quaint ethnicity, and other forms of landscape-based exotica. It has the same central device as Honghegu, too: the narrative is told largely by a British civilian serving with Younghusband, a younger educated man who speaks Tibetan and disagrees with the British project.  Both films are mainly about battles in which the British slaughter lightly armed Tibetans with their Maxim guns. Both invent a young and handsome Tibetan character who has extraordinary prowess in battle. Both show these battles in great detail, particularly the deaths on the Tibetan side, and have romantic or sentimental sub-plots featuring a bond between a Tibetan and a member of the British forces. Both devote much time to showing the arrogance of the British generals, and in both the leading British figures speak with scottish accents – the British general in one film and the British translator in the other (apart from those scenes where the translator is played by an Australian)[in fact, was going for an Ulster accent]. Jiangzi 1904 has important features that, despite its story line, distinguish it from the genre of patriotic melodrama and distance it from the Hollywood- style ‘updated main melody film’.

Both films are mainly about battles in which the British slaughter lightly armed Tibetans with their Maxim guns. Both invent a young and handsome Tibetan character who has extraordinary prowess in battle. Both show these battles in great detail, particularly the deaths on the Tibetan side, and have romantic or sentimental sub-plots featuring a bond between a Tibetan and a member of the British forces. Both devote much time to showing the arrogance of the British generals, and in both the leading British figures speak with scottish accents – the British general in one film and the British translator in the other (apart from those scenes where the translator is played by an Australian)[in fact, was going for an Ulster accent]. Jiangzi 1904 has important features that, despite its story line, distinguish it from the genre of patriotic melodrama and distance it from the Hollywood- style ‘updated main melody film’.  It is not presented as historical fantasy: the main historical characters – the British leaders, the Qing and Tibetan officials – are presented under their own names. The film focuses on the psychology of the British officers in the face of their predicament and the tensions that emerged between them, with almost all the dialogue in the film spoken by them. as in Honghegu, the British characters speak in their own language instead of being dubbed, but unlike Honghegu, the Tibetan characters also speak their own language throughout the film, perhaps the first time Tibetan has been spoken at length in a CCTV drama series. There is no scene showing mass suicide by the Tibetan fighters after they are defeated at Gyantse, and some are shown escaping, as indeed several did. The negotiating sessions between the British, the Tibetans and the Qing are shown in considerable detail, to an extent that requires serious attention from the viewer and counters Hollywood narrative conventions.

It is not presented as historical fantasy: the main historical characters – the British leaders, the Qing and Tibetan officials – are presented under their own names. The film focuses on the psychology of the British officers in the face of their predicament and the tensions that emerged between them, with almost all the dialogue in the film spoken by them. as in Honghegu, the British characters speak in their own language instead of being dubbed, but unlike Honghegu, the Tibetan characters also speak their own language throughout the film, perhaps the first time Tibetan has been spoken at length in a CCTV drama series. There is no scene showing mass suicide by the Tibetan fighters after they are defeated at Gyantse, and some are shown escaping, as indeed several did. The negotiating sessions between the British, the Tibetans and the Qing are shown in considerable detail, to an extent that requires serious attention from the viewer and counters Hollywood narrative conventions.  The story opens in 1943, with David Austin, a British anthropologist who speaks Tibetan, on his way through nepal towards Tibet. He recalls his friendship with an educated, english-speaking Tibetan youth called ngawang Dondrup whom he had known in Kathmandu in about 1902. He then thinks of his time in Tibet a year or so later as Younghusband’s interpreter on the British expedition, referred to in the film by its correct title as the Tibet Frontier Mission.

The story opens in 1943, with David Austin, a British anthropologist who speaks Tibetan, on his way through nepal towards Tibet. He recalls his friendship with an educated, english-speaking Tibetan youth called ngawang Dondrup whom he had known in Kathmandu in about 1902. He then thinks of his time in Tibet a year or so later as Younghusband’s interpreter on the British expedition, referred to in the film by its correct title as the Tibet Frontier Mission.  The film cuts to a meeting of Curzon’s cabinet in Calcutta in 1903, at which Curzon calls Tibet ‘uncivilised’ and says ‘military pressure can help bring friendly relations’. We then see austin with Younghusband and the troops in Tibet, who are led by General MacDonald. He describes the place as ‘all too beautiful, too miraculous. Quite unaccounted for on the map. an isolated and barren world.’ Younghusband refers to Tibetans as a ‘bunch of aboriginals’ and notes that ‘to conquer a territory’ one must used ‘armed suppression’.

The film cuts to a meeting of Curzon’s cabinet in Calcutta in 1903, at which Curzon calls Tibet ‘uncivilised’ and says ‘military pressure can help bring friendly relations’. We then see austin with Younghusband and the troops in Tibet, who are led by General MacDonald. He describes the place as ‘all too beautiful, too miraculous. Quite unaccounted for on the map. an isolated and barren world.’ Younghusband refers to Tibetans as a ‘bunch of aboriginals’ and notes that ‘to conquer a territory’ one must used ‘armed suppression’.  Thus far, the intellectual content of the drama seems indistinguishable from Feng’s film. But increasingly the narrative slows down to show drawn out attempts at negotiations by the Tibetan side, at which Qing officials play a prominent role alongside the Tibetan nobles. Younghusband displays arrogance and insistence, as we would expect, but it leads to discontent from austin and heated arguments between MacDonald and Younghusband, who at one point is confined to his quarters by the General. Paradoxically, when the massacre of Chumik shenko takes place, it is, however, MacDonald who orders his Maxim gunners to continue firing at the retreating Tibetans, despite Younghusband calling the killing ‘senseless’.

Thus far, the intellectual content of the drama seems indistinguishable from Feng’s film. But increasingly the narrative slows down to show drawn out attempts at negotiations by the Tibetan side, at which Qing officials play a prominent role alongside the Tibetan nobles. Younghusband displays arrogance and insistence, as we would expect, but it leads to discontent from austin and heated arguments between MacDonald and Younghusband, who at one point is confined to his quarters by the General. Paradoxically, when the massacre of Chumik shenko takes place, it is, however, MacDonald who orders his Maxim gunners to continue firing at the retreating Tibetans, despite Younghusband calling the killing ‘senseless’.  Austin meets his former Tibetan friend, Ngawang Dondrup, now leading the local Tibetan troops. ngawang returns the watch that austin had once given him and punches austin, who calls him ‘a fucking barbarian’ while the two grapple aimlessly on the ground. austin tries several times to persuade Younghusband to stop the killing, but is told that reason is more important than sentiment. MacDonald even says, ‘Younghusband, you are mad, completely mad’, and confides to austin that he misses his fiancée and that this war ‘doesn’t seem right’. as the mission advances towards Gyantse, Younghusband faces the prospect of capture and defeat when Tibetans stage the night-raid at Changlo. The raid is led by ngawang Dondrup, joined this time by an unnamed Tibetan woman fighter armed with bow and arrow. They enter the house where Younghusband is staying, killing several British soldiers, but are unable to capture the commander. at nenying, the British overrun the monastery and Younghusband holds the monks at gunpoint, but is amazed by the intricate art work in the murals which, he says, ‘reflects a nation with intelligence, culture and wisdom’.

Austin meets his former Tibetan friend, Ngawang Dondrup, now leading the local Tibetan troops. ngawang returns the watch that austin had once given him and punches austin, who calls him ‘a fucking barbarian’ while the two grapple aimlessly on the ground. austin tries several times to persuade Younghusband to stop the killing, but is told that reason is more important than sentiment. MacDonald even says, ‘Younghusband, you are mad, completely mad’, and confides to austin that he misses his fiancée and that this war ‘doesn’t seem right’. as the mission advances towards Gyantse, Younghusband faces the prospect of capture and defeat when Tibetans stage the night-raid at Changlo. The raid is led by ngawang Dondrup, joined this time by an unnamed Tibetan woman fighter armed with bow and arrow. They enter the house where Younghusband is staying, killing several British soldiers, but are unable to capture the commander. at nenying, the British overrun the monastery and Younghusband holds the monks at gunpoint, but is amazed by the intricate art work in the murals which, he says, ‘reflects a nation with intelligence, culture and wisdom’.  He finds Austin praying before a Buddha statue and asking it to ‘forgive us for our violent actions’. Younghusband joins him silently in prayer. The battle to take the fort of Gyantse is shown in detail, but with no mass suicide. It ends with Ngawang shooting his father dead before the British can take him prisoner, as his father had requested earlier, and he is able to escape by horse with the Tibetan woman. Finally, the film returns to 1943 where Austin, saying ‘People here have their own religion, just like we have ours’, reaches Lhasa and is reunited with ngawang, now a monk, who forgives him for his involvement in the war. Jiangzi 1904 thus includes an over-weighty sub-plot featuring the Austin– Ngawang friendship, and a maudlin resolution typical of contemporary Chinese melodrama. But by otherwise avoiding exaggeration and factual distortion, it presents a very different account of militant Tibetan patriotism from that shown in Honghegu.

He finds Austin praying before a Buddha statue and asking it to ‘forgive us for our violent actions’. Younghusband joins him silently in prayer. The battle to take the fort of Gyantse is shown in detail, but with no mass suicide. It ends with Ngawang shooting his father dead before the British can take him prisoner, as his father had requested earlier, and he is able to escape by horse with the Tibetan woman. Finally, the film returns to 1943 where Austin, saying ‘People here have their own religion, just like we have ours’, reaches Lhasa and is reunited with ngawang, now a monk, who forgives him for his involvement in the war. Jiangzi 1904 thus includes an over-weighty sub-plot featuring the Austin– Ngawang friendship, and a maudlin resolution typical of contemporary Chinese melodrama. But by otherwise avoiding exaggeration and factual distortion, it presents a very different account of militant Tibetan patriotism from that shown in Honghegu.  It is not that the military zeal or bravery of the Tibetans is different: from the perspective of government funders, this is effectively the same film, in that it too glorifies Tibetan fighting spirit against duplicitous foreigners. But it remains closer to the historical record, and presents credible representations of Curzon, the British camp and other details, allowing, as we have seen, some com- plexity in the characters of Younghusband and MacDonald, both of whom are shown to change in varying and inconsistent ways, as people might do under the pressures that they faced. It represents China’s role in Tibet mainly by showing Qing officials taking a leading but ineffectual role in the negotiations rather than by polemical assertions, depicting them as vacillating and weak in their failure to support Tibetans in the fight against the British. Its reconstruction of Tibetan subjectivity is predictable but relatively sensitive – instead of the half-naked serf Gesang with his primitive love for girl and country, Ngawang is shown to have a wide range of interests and ideas: he is an educated aristocrat, fluent in english and Chinese as well as in his own language, and he has to struggle to reconcile the horror of war with his former affection for his British friend.

It is not that the military zeal or bravery of the Tibetans is different: from the perspective of government funders, this is effectively the same film, in that it too glorifies Tibetan fighting spirit against duplicitous foreigners. But it remains closer to the historical record, and presents credible representations of Curzon, the British camp and other details, allowing, as we have seen, some com- plexity in the characters of Younghusband and MacDonald, both of whom are shown to change in varying and inconsistent ways, as people might do under the pressures that they faced. It represents China’s role in Tibet mainly by showing Qing officials taking a leading but ineffectual role in the negotiations rather than by polemical assertions, depicting them as vacillating and weak in their failure to support Tibetans in the fight against the British. Its reconstruction of Tibetan subjectivity is predictable but relatively sensitive – instead of the half-naked serf Gesang with his primitive love for girl and country, Ngawang is shown to have a wide range of interests and ideas: he is an educated aristocrat, fluent in english and Chinese as well as in his own language, and he has to struggle to reconcile the horror of war with his former affection for his British friend.  These elements of the drama are not unsuccessful, even though the basic storyline and message are so close to those of Honghegu. They suggest that the credibility of historical reconstruction is not primarily due to the historical accuracy of a text or drama, or even to relative restraint in its writing, but to its underlying ideology. In Jiangzi 1904, the discourse of class struggle is completely absent, and so is the depiction of Tibetans as backward, ignorant or superstitious. The lead Tibetan character is highly educated, not a half-naked serf, and there is no trace of Maoist progressivism or social evolution, with the only sign of Tibetan backwardness being their limited range of weapons. The stock figure of the educated Tibetan who has learnt English in India appears in numerous Chinese films about Tibet, but in Jiangzi 1904 he is the main Tibetan character.

These elements of the drama are not unsuccessful, even though the basic storyline and message are so close to those of Honghegu. They suggest that the credibility of historical reconstruction is not primarily due to the historical accuracy of a text or drama, or even to relative restraint in its writing, but to its underlying ideology. In Jiangzi 1904, the discourse of class struggle is completely absent, and so is the depiction of Tibetans as backward, ignorant or superstitious. The lead Tibetan character is highly educated, not a half-naked serf, and there is no trace of Maoist progressivism or social evolution, with the only sign of Tibetan backwardness being their limited range of weapons. The stock figure of the educated Tibetan who has learnt English in India appears in numerous Chinese films about Tibet, but in Jiangzi 1904 he is the main Tibetan character.  Much of the excess ideological baggage of the 1960s and the 1980s, the framing concepts and presumptions within which political messages were placed, has been dispensed with. We encounter the familiar exotic thrill in Tibetan landscape and culture, but fascination with it is ascribed to certain British characters and not indulged in by the camera or the film itself. The absence of class struggle and social evolution theory from the mix already radically changes the nature of the project, because these, while unimportant to the main action of this film, have greater impact than themes of patriotism or anti-imperialism on the rendering of Tibetan subjectivity. Put simply, a writer who presumes a person to be backward by nature of their ethnicity or class is likely to find it hard to represent in any depth their capacity for sentiment and thought, and more likely to portray them through heroic action.

Much of the excess ideological baggage of the 1960s and the 1980s, the framing concepts and presumptions within which political messages were placed, has been dispensed with. We encounter the familiar exotic thrill in Tibetan landscape and culture, but fascination with it is ascribed to certain British characters and not indulged in by the camera or the film itself. The absence of class struggle and social evolution theory from the mix already radically changes the nature of the project, because these, while unimportant to the main action of this film, have greater impact than themes of patriotism or anti-imperialism on the rendering of Tibetan subjectivity. Put simply, a writer who presumes a person to be backward by nature of their ethnicity or class is likely to find it hard to represent in any depth their capacity for sentiment and thought, and more likely to portray them through heroic action.  It could thus be argued that more important to effective representation than historical accuracy is the ability of a film or text to maintain a distance from what we might call secondary ideologies, especially ideologies of the person – concepts and assumptions that treat foreign subjectivity as reducible. It may thus be not the glorification of patriotism in the final part of Honghegu or its formulaic romanticism that makes it a heavily laden project, but its underlying assumptions about Tibetan personhood. Once again, it might be elements that are marginal to the storyline, apparently decorative aspects of the film, which have the greater impact.

It could thus be argued that more important to effective representation than historical accuracy is the ability of a film or text to maintain a distance from what we might call secondary ideologies, especially ideologies of the person – concepts and assumptions that treat foreign subjectivity as reducible. It may thus be not the glorification of patriotism in the final part of Honghegu or its formulaic romanticism that makes it a heavily laden project, but its underlying assumptions about Tibetan personhood. Once again, it might be elements that are marginal to the storyline, apparently decorative aspects of the film, which have the greater impact.  The relative success of Jiangzi 1904 in representing Tibetans and Tibetan history is shown in its treatment of the pivotal event in Chinese accounts of the invasion – the Changlo raid of 5 May 1904. That episode is represented in the television series without the teleological certainty of the British historians – it portrays the situation as it might have been experienced by the participants at the time, with the British facing imminent disaster and the Tibetans seemingly about to win. It thus exploits the opportunity in narrative technique that arises from separating subjective description from historical outcome. There is, in fact, considerable evidence from historians that at several times during the British advance the Tibetans came close to victory, failing only when the British were able to get advanced weaponry within range of their attackers, or because the Tibetan government had ordered its soldiers not to fight. Fleming argues that the Tibetans would very probably have overrun the sleeping British troops that night at Changlo if they had simply climbed the protective walls instead of shooting from outside, since the embrasures built by the taller Indian troops were too high for them to shoot through effectively.

The relative success of Jiangzi 1904 in representing Tibetans and Tibetan history is shown in its treatment of the pivotal event in Chinese accounts of the invasion – the Changlo raid of 5 May 1904. That episode is represented in the television series without the teleological certainty of the British historians – it portrays the situation as it might have been experienced by the participants at the time, with the British facing imminent disaster and the Tibetans seemingly about to win. It thus exploits the opportunity in narrative technique that arises from separating subjective description from historical outcome. There is, in fact, considerable evidence from historians that at several times during the British advance the Tibetans came close to victory, failing only when the British were able to get advanced weaponry within range of their attackers, or because the Tibetan government had ordered its soldiers not to fight. Fleming argues that the Tibetans would very probably have overrun the sleeping British troops that night at Changlo if they had simply climbed the protective walls instead of shooting from outside, since the embrasures built by the taller Indian troops were too high for them to shoot through effectively.  At Tuna in the winter of 1903, the British had been completely vulnerable because many of their weapons could not operate at sub-zero temperatures, but Tibetans had been ordered not to attack, because their leaders had decided on a policy of fighting only in self-defence, possibly in order to lessen their problems with the Qing court, which was insisting that the Tibetans should not fight at all.

At Tuna in the winter of 1903, the British had been completely vulnerable because many of their weapons could not operate at sub-zero temperatures, but Tibetans had been ordered not to attack, because their leaders had decided on a policy of fighting only in self-defence, possibly in order to lessen their problems with the Qing court, which was insisting that the Tibetans should not fight at all.  In its portrayal of the raid at Changlo, Jiangzi 1904 shows Younghusband in a state of acute anxiety as he faces almost certain defeat. Whether that was in fact the case is unknown, because he of course gives no hint of such emotions in his accounts written at the time – in his first cable to Lord Curzon after the raid was suppressed he wrote that two hours later ‘it was a lovely peaceful morning with skylarks singing and sparrows chirping unconcernedly away’, a suspiciously lyrical claim to normalcy. But the film’s creation of a credible subjectivity for Younghusband during that episode is outside the bounds of a historian’s precision: it is no more uncertain than any other interpretation, although more likely than his own account of his emotions or those in British records. History in Jiangzi 1904 is structured around a sentimental and over- wrought friendship between Austin and Ngawang, but it presents the Tibetans as credible agents of their future, with persuasive moral logic to justify their actions, and shows the British officers as experiencing complexity and doubt as well.

In its portrayal of the raid at Changlo, Jiangzi 1904 shows Younghusband in a state of acute anxiety as he faces almost certain defeat. Whether that was in fact the case is unknown, because he of course gives no hint of such emotions in his accounts written at the time – in his first cable to Lord Curzon after the raid was suppressed he wrote that two hours later ‘it was a lovely peaceful morning with skylarks singing and sparrows chirping unconcernedly away’, a suspiciously lyrical claim to normalcy. But the film’s creation of a credible subjectivity for Younghusband during that episode is outside the bounds of a historian’s precision: it is no more uncertain than any other interpretation, although more likely than his own account of his emotions or those in British records. History in Jiangzi 1904 is structured around a sentimental and over- wrought friendship between Austin and Ngawang, but it presents the Tibetans as credible agents of their future, with persuasive moral logic to justify their actions, and shows the British officers as experiencing complexity and doubt as well.

Special 10th Anniversary Trailer

Both films are mainly about battles in which the British slaughter lightly armed Tibetans with their Maxim guns. Both invent a young and handsome Tibetan character who has extraordinary prowess in battle. Both show these battles in great detail, particularly the deaths on the Tibetan side, and have romantic or sentimental sub-plots featuring a bond between a Tibetan and a member of the British forces. Both devote much time to showing the arrogance of the British generals, and in both the leading British figures speak with scottish accents – the British general in one film and the British translator in the other (apart from those scenes where the translator is played by an Australian)[in fact, was going for an Ulster accent]. Jiangzi 1904 has important features that, despite its story line, distinguish it from the genre of patriotic melodrama and distance it from the Hollywood- style ‘updated main melody film’.

Both films are mainly about battles in which the British slaughter lightly armed Tibetans with their Maxim guns. Both invent a young and handsome Tibetan character who has extraordinary prowess in battle. Both show these battles in great detail, particularly the deaths on the Tibetan side, and have romantic or sentimental sub-plots featuring a bond between a Tibetan and a member of the British forces. Both devote much time to showing the arrogance of the British generals, and in both the leading British figures speak with scottish accents – the British general in one film and the British translator in the other (apart from those scenes where the translator is played by an Australian)[in fact, was going for an Ulster accent]. Jiangzi 1904 has important features that, despite its story line, distinguish it from the genre of patriotic melodrama and distance it from the Hollywood- style ‘updated main melody film’.  It is not presented as historical fantasy: the main historical characters – the British leaders, the Qing and Tibetan officials – are presented under their own names. The film focuses on the psychology of the British officers in the face of their predicament and the tensions that emerged between them, with almost all the dialogue in the film spoken by them. as in Honghegu, the British characters speak in their own language instead of being dubbed, but unlike Honghegu, the Tibetan characters also speak their own language throughout the film, perhaps the first time Tibetan has been spoken at length in a CCTV drama series. There is no scene showing mass suicide by the Tibetan fighters after they are defeated at Gyantse, and some are shown escaping, as indeed several did. The negotiating sessions between the British, the Tibetans and the Qing are shown in considerable detail, to an extent that requires serious attention from the viewer and counters Hollywood narrative conventions.

It is not presented as historical fantasy: the main historical characters – the British leaders, the Qing and Tibetan officials – are presented under their own names. The film focuses on the psychology of the British officers in the face of their predicament and the tensions that emerged between them, with almost all the dialogue in the film spoken by them. as in Honghegu, the British characters speak in their own language instead of being dubbed, but unlike Honghegu, the Tibetan characters also speak their own language throughout the film, perhaps the first time Tibetan has been spoken at length in a CCTV drama series. There is no scene showing mass suicide by the Tibetan fighters after they are defeated at Gyantse, and some are shown escaping, as indeed several did. The negotiating sessions between the British, the Tibetans and the Qing are shown in considerable detail, to an extent that requires serious attention from the viewer and counters Hollywood narrative conventions.  The story opens in 1943, with David Austin, a British anthropologist who speaks Tibetan, on his way through nepal towards Tibet. He recalls his friendship with an educated, english-speaking Tibetan youth called ngawang Dondrup whom he had known in Kathmandu in about 1902. He then thinks of his time in Tibet a year or so later as Younghusband’s interpreter on the British expedition, referred to in the film by its correct title as the Tibet Frontier Mission.

The story opens in 1943, with David Austin, a British anthropologist who speaks Tibetan, on his way through nepal towards Tibet. He recalls his friendship with an educated, english-speaking Tibetan youth called ngawang Dondrup whom he had known in Kathmandu in about 1902. He then thinks of his time in Tibet a year or so later as Younghusband’s interpreter on the British expedition, referred to in the film by its correct title as the Tibet Frontier Mission.  The film cuts to a meeting of Curzon’s cabinet in Calcutta in 1903, at which Curzon calls Tibet ‘uncivilised’ and says ‘military pressure can help bring friendly relations’. We then see austin with Younghusband and the troops in Tibet, who are led by General MacDonald. He describes the place as ‘all too beautiful, too miraculous. Quite unaccounted for on the map. an isolated and barren world.’ Younghusband refers to Tibetans as a ‘bunch of aboriginals’ and notes that ‘to conquer a territory’ one must used ‘armed suppression’.

The film cuts to a meeting of Curzon’s cabinet in Calcutta in 1903, at which Curzon calls Tibet ‘uncivilised’ and says ‘military pressure can help bring friendly relations’. We then see austin with Younghusband and the troops in Tibet, who are led by General MacDonald. He describes the place as ‘all too beautiful, too miraculous. Quite unaccounted for on the map. an isolated and barren world.’ Younghusband refers to Tibetans as a ‘bunch of aboriginals’ and notes that ‘to conquer a territory’ one must used ‘armed suppression’.  Thus far, the intellectual content of the drama seems indistinguishable from Feng’s film. But increasingly the narrative slows down to show drawn out attempts at negotiations by the Tibetan side, at which Qing officials play a prominent role alongside the Tibetan nobles. Younghusband displays arrogance and insistence, as we would expect, but it leads to discontent from austin and heated arguments between MacDonald and Younghusband, who at one point is confined to his quarters by the General. Paradoxically, when the massacre of Chumik shenko takes place, it is, however, MacDonald who orders his Maxim gunners to continue firing at the retreating Tibetans, despite Younghusband calling the killing ‘senseless’.

Thus far, the intellectual content of the drama seems indistinguishable from Feng’s film. But increasingly the narrative slows down to show drawn out attempts at negotiations by the Tibetan side, at which Qing officials play a prominent role alongside the Tibetan nobles. Younghusband displays arrogance and insistence, as we would expect, but it leads to discontent from austin and heated arguments between MacDonald and Younghusband, who at one point is confined to his quarters by the General. Paradoxically, when the massacre of Chumik shenko takes place, it is, however, MacDonald who orders his Maxim gunners to continue firing at the retreating Tibetans, despite Younghusband calling the killing ‘senseless’.  Austin meets his former Tibetan friend, Ngawang Dondrup, now leading the local Tibetan troops. ngawang returns the watch that austin had once given him and punches austin, who calls him ‘a fucking barbarian’ while the two grapple aimlessly on the ground. austin tries several times to persuade Younghusband to stop the killing, but is told that reason is more important than sentiment. MacDonald even says, ‘Younghusband, you are mad, completely mad’, and confides to austin that he misses his fiancée and that this war ‘doesn’t seem right’. as the mission advances towards Gyantse, Younghusband faces the prospect of capture and defeat when Tibetans stage the night-raid at Changlo. The raid is led by ngawang Dondrup, joined this time by an unnamed Tibetan woman fighter armed with bow and arrow. They enter the house where Younghusband is staying, killing several British soldiers, but are unable to capture the commander. at nenying, the British overrun the monastery and Younghusband holds the monks at gunpoint, but is amazed by the intricate art work in the murals which, he says, ‘reflects a nation with intelligence, culture and wisdom’.

Austin meets his former Tibetan friend, Ngawang Dondrup, now leading the local Tibetan troops. ngawang returns the watch that austin had once given him and punches austin, who calls him ‘a fucking barbarian’ while the two grapple aimlessly on the ground. austin tries several times to persuade Younghusband to stop the killing, but is told that reason is more important than sentiment. MacDonald even says, ‘Younghusband, you are mad, completely mad’, and confides to austin that he misses his fiancée and that this war ‘doesn’t seem right’. as the mission advances towards Gyantse, Younghusband faces the prospect of capture and defeat when Tibetans stage the night-raid at Changlo. The raid is led by ngawang Dondrup, joined this time by an unnamed Tibetan woman fighter armed with bow and arrow. They enter the house where Younghusband is staying, killing several British soldiers, but are unable to capture the commander. at nenying, the British overrun the monastery and Younghusband holds the monks at gunpoint, but is amazed by the intricate art work in the murals which, he says, ‘reflects a nation with intelligence, culture and wisdom’.  He finds Austin praying before a Buddha statue and asking it to ‘forgive us for our violent actions’. Younghusband joins him silently in prayer. The battle to take the fort of Gyantse is shown in detail, but with no mass suicide. It ends with Ngawang shooting his father dead before the British can take him prisoner, as his father had requested earlier, and he is able to escape by horse with the Tibetan woman. Finally, the film returns to 1943 where Austin, saying ‘People here have their own religion, just like we have ours’, reaches Lhasa and is reunited with ngawang, now a monk, who forgives him for his involvement in the war. Jiangzi 1904 thus includes an over-weighty sub-plot featuring the Austin– Ngawang friendship, and a maudlin resolution typical of contemporary Chinese melodrama. But by otherwise avoiding exaggeration and factual distortion, it presents a very different account of militant Tibetan patriotism from that shown in Honghegu.

He finds Austin praying before a Buddha statue and asking it to ‘forgive us for our violent actions’. Younghusband joins him silently in prayer. The battle to take the fort of Gyantse is shown in detail, but with no mass suicide. It ends with Ngawang shooting his father dead before the British can take him prisoner, as his father had requested earlier, and he is able to escape by horse with the Tibetan woman. Finally, the film returns to 1943 where Austin, saying ‘People here have their own religion, just like we have ours’, reaches Lhasa and is reunited with ngawang, now a monk, who forgives him for his involvement in the war. Jiangzi 1904 thus includes an over-weighty sub-plot featuring the Austin– Ngawang friendship, and a maudlin resolution typical of contemporary Chinese melodrama. But by otherwise avoiding exaggeration and factual distortion, it presents a very different account of militant Tibetan patriotism from that shown in Honghegu.  It is not that the military zeal or bravery of the Tibetans is different: from the perspective of government funders, this is effectively the same film, in that it too glorifies Tibetan fighting spirit against duplicitous foreigners. But it remains closer to the historical record, and presents credible representations of Curzon, the British camp and other details, allowing, as we have seen, some com- plexity in the characters of Younghusband and MacDonald, both of whom are shown to change in varying and inconsistent ways, as people might do under the pressures that they faced. It represents China’s role in Tibet mainly by showing Qing officials taking a leading but ineffectual role in the negotiations rather than by polemical assertions, depicting them as vacillating and weak in their failure to support Tibetans in the fight against the British. Its reconstruction of Tibetan subjectivity is predictable but relatively sensitive – instead of the half-naked serf Gesang with his primitive love for girl and country, Ngawang is shown to have a wide range of interests and ideas: he is an educated aristocrat, fluent in english and Chinese as well as in his own language, and he has to struggle to reconcile the horror of war with his former affection for his British friend.

It is not that the military zeal or bravery of the Tibetans is different: from the perspective of government funders, this is effectively the same film, in that it too glorifies Tibetan fighting spirit against duplicitous foreigners. But it remains closer to the historical record, and presents credible representations of Curzon, the British camp and other details, allowing, as we have seen, some com- plexity in the characters of Younghusband and MacDonald, both of whom are shown to change in varying and inconsistent ways, as people might do under the pressures that they faced. It represents China’s role in Tibet mainly by showing Qing officials taking a leading but ineffectual role in the negotiations rather than by polemical assertions, depicting them as vacillating and weak in their failure to support Tibetans in the fight against the British. Its reconstruction of Tibetan subjectivity is predictable but relatively sensitive – instead of the half-naked serf Gesang with his primitive love for girl and country, Ngawang is shown to have a wide range of interests and ideas: he is an educated aristocrat, fluent in english and Chinese as well as in his own language, and he has to struggle to reconcile the horror of war with his former affection for his British friend.  These elements of the drama are not unsuccessful, even though the basic storyline and message are so close to those of Honghegu. They suggest that the credibility of historical reconstruction is not primarily due to the historical accuracy of a text or drama, or even to relative restraint in its writing, but to its underlying ideology. In Jiangzi 1904, the discourse of class struggle is completely absent, and so is the depiction of Tibetans as backward, ignorant or superstitious. The lead Tibetan character is highly educated, not a half-naked serf, and there is no trace of Maoist progressivism or social evolution, with the only sign of Tibetan backwardness being their limited range of weapons. The stock figure of the educated Tibetan who has learnt English in India appears in numerous Chinese films about Tibet, but in Jiangzi 1904 he is the main Tibetan character.

These elements of the drama are not unsuccessful, even though the basic storyline and message are so close to those of Honghegu. They suggest that the credibility of historical reconstruction is not primarily due to the historical accuracy of a text or drama, or even to relative restraint in its writing, but to its underlying ideology. In Jiangzi 1904, the discourse of class struggle is completely absent, and so is the depiction of Tibetans as backward, ignorant or superstitious. The lead Tibetan character is highly educated, not a half-naked serf, and there is no trace of Maoist progressivism or social evolution, with the only sign of Tibetan backwardness being their limited range of weapons. The stock figure of the educated Tibetan who has learnt English in India appears in numerous Chinese films about Tibet, but in Jiangzi 1904 he is the main Tibetan character.  Much of the excess ideological baggage of the 1960s and the 1980s, the framing concepts and presumptions within which political messages were placed, has been dispensed with. We encounter the familiar exotic thrill in Tibetan landscape and culture, but fascination with it is ascribed to certain British characters and not indulged in by the camera or the film itself. The absence of class struggle and social evolution theory from the mix already radically changes the nature of the project, because these, while unimportant to the main action of this film, have greater impact than themes of patriotism or anti-imperialism on the rendering of Tibetan subjectivity. Put simply, a writer who presumes a person to be backward by nature of their ethnicity or class is likely to find it hard to represent in any depth their capacity for sentiment and thought, and more likely to portray them through heroic action.

Much of the excess ideological baggage of the 1960s and the 1980s, the framing concepts and presumptions within which political messages were placed, has been dispensed with. We encounter the familiar exotic thrill in Tibetan landscape and culture, but fascination with it is ascribed to certain British characters and not indulged in by the camera or the film itself. The absence of class struggle and social evolution theory from the mix already radically changes the nature of the project, because these, while unimportant to the main action of this film, have greater impact than themes of patriotism or anti-imperialism on the rendering of Tibetan subjectivity. Put simply, a writer who presumes a person to be backward by nature of their ethnicity or class is likely to find it hard to represent in any depth their capacity for sentiment and thought, and more likely to portray them through heroic action.  It could thus be argued that more important to effective representation than historical accuracy is the ability of a film or text to maintain a distance from what we might call secondary ideologies, especially ideologies of the person – concepts and assumptions that treat foreign subjectivity as reducible. It may thus be not the glorification of patriotism in the final part of Honghegu or its formulaic romanticism that makes it a heavily laden project, but its underlying assumptions about Tibetan personhood. Once again, it might be elements that are marginal to the storyline, apparently decorative aspects of the film, which have the greater impact.

It could thus be argued that more important to effective representation than historical accuracy is the ability of a film or text to maintain a distance from what we might call secondary ideologies, especially ideologies of the person – concepts and assumptions that treat foreign subjectivity as reducible. It may thus be not the glorification of patriotism in the final part of Honghegu or its formulaic romanticism that makes it a heavily laden project, but its underlying assumptions about Tibetan personhood. Once again, it might be elements that are marginal to the storyline, apparently decorative aspects of the film, which have the greater impact.  The relative success of Jiangzi 1904 in representing Tibetans and Tibetan history is shown in its treatment of the pivotal event in Chinese accounts of the invasion – the Changlo raid of 5 May 1904. That episode is represented in the television series without the teleological certainty of the British historians – it portrays the situation as it might have been experienced by the participants at the time, with the British facing imminent disaster and the Tibetans seemingly about to win. It thus exploits the opportunity in narrative technique that arises from separating subjective description from historical outcome. There is, in fact, considerable evidence from historians that at several times during the British advance the Tibetans came close to victory, failing only when the British were able to get advanced weaponry within range of their attackers, or because the Tibetan government had ordered its soldiers not to fight. Fleming argues that the Tibetans would very probably have overrun the sleeping British troops that night at Changlo if they had simply climbed the protective walls instead of shooting from outside, since the embrasures built by the taller Indian troops were too high for them to shoot through effectively.

The relative success of Jiangzi 1904 in representing Tibetans and Tibetan history is shown in its treatment of the pivotal event in Chinese accounts of the invasion – the Changlo raid of 5 May 1904. That episode is represented in the television series without the teleological certainty of the British historians – it portrays the situation as it might have been experienced by the participants at the time, with the British facing imminent disaster and the Tibetans seemingly about to win. It thus exploits the opportunity in narrative technique that arises from separating subjective description from historical outcome. There is, in fact, considerable evidence from historians that at several times during the British advance the Tibetans came close to victory, failing only when the British were able to get advanced weaponry within range of their attackers, or because the Tibetan government had ordered its soldiers not to fight. Fleming argues that the Tibetans would very probably have overrun the sleeping British troops that night at Changlo if they had simply climbed the protective walls instead of shooting from outside, since the embrasures built by the taller Indian troops were too high for them to shoot through effectively.  At Tuna in the winter of 1903, the British had been completely vulnerable because many of their weapons could not operate at sub-zero temperatures, but Tibetans had been ordered not to attack, because their leaders had decided on a policy of fighting only in self-defence, possibly in order to lessen their problems with the Qing court, which was insisting that the Tibetans should not fight at all.

At Tuna in the winter of 1903, the British had been completely vulnerable because many of their weapons could not operate at sub-zero temperatures, but Tibetans had been ordered not to attack, because their leaders had decided on a policy of fighting only in self-defence, possibly in order to lessen their problems with the Qing court, which was insisting that the Tibetans should not fight at all.  In its portrayal of the raid at Changlo, Jiangzi 1904 shows Younghusband in a state of acute anxiety as he faces almost certain defeat. Whether that was in fact the case is unknown, because he of course gives no hint of such emotions in his accounts written at the time – in his first cable to Lord Curzon after the raid was suppressed he wrote that two hours later ‘it was a lovely peaceful morning with skylarks singing and sparrows chirping unconcernedly away’, a suspiciously lyrical claim to normalcy. But the film’s creation of a credible subjectivity for Younghusband during that episode is outside the bounds of a historian’s precision: it is no more uncertain than any other interpretation, although more likely than his own account of his emotions or those in British records. History in Jiangzi 1904 is structured around a sentimental and over- wrought friendship between Austin and Ngawang, but it presents the Tibetans as credible agents of their future, with persuasive moral logic to justify their actions, and shows the British officers as experiencing complexity and doubt as well.

In its portrayal of the raid at Changlo, Jiangzi 1904 shows Younghusband in a state of acute anxiety as he faces almost certain defeat. Whether that was in fact the case is unknown, because he of course gives no hint of such emotions in his accounts written at the time – in his first cable to Lord Curzon after the raid was suppressed he wrote that two hours later ‘it was a lovely peaceful morning with skylarks singing and sparrows chirping unconcernedly away’, a suspiciously lyrical claim to normalcy. But the film’s creation of a credible subjectivity for Younghusband during that episode is outside the bounds of a historian’s precision: it is no more uncertain than any other interpretation, although more likely than his own account of his emotions or those in British records. History in Jiangzi 1904 is structured around a sentimental and over- wrought friendship between Austin and Ngawang, but it presents the Tibetans as credible agents of their future, with persuasive moral logic to justify their actions, and shows the British officers as experiencing complexity and doubt as well.

From: Robert Barnett, Columbia University, New York, USA rjb58@columbia.edu

Special 10th Anniversary Trailer

The Original Official Trailer

Part I

Scene 1: Introduction

Scene 2: Beginning of a beautiful, tragic friendship

Supposed to be set in Calcutta in British India but for some reason the site is unmistakably Kathmandu. Notice the prevalence of jeans, T-shirts and mopeds in 1903 Nepal, far more modern and technologically-advanced than how it ended the century, as we are introduced properly to our hero- Austin- who literally bumps into the man who will haunt the rest of his life. Note the Indian soldiers; it is they that lost the jewel in the Imperial Crown as shown here.

Scene 3: Lord Curzon and Younghusband explain the proposed Liberation

This scene early in the first instalment of the inspirational Gyantse 1904- The British Liberation of Tibet starts in the meeting room of Lord Curzon's private residence in Calcutta June 18, 1903 and ends with his plan in his office. The cassus belli is clear- besides increasing Russian influence and continuing doleful oppression of the Chinese, as Curzon would write, the situation was now getting completely out of hand:

We now learn that Tibetan troops attacked Nepalese yaks on the frontier and carried many of them off. This is an overt act of hostility.Scene 4: The British entering Tibet, 1903

Here we join Colonel Younghusband and his intrepid Scot interpreter David Austin (yours truly) as they lead the British into Tibet to liberate that unfortunate people from Chinese fascist, imperialist oppression. It is here that Younghusband levels the damning charges against the Tibetans- the Dalai Lama having the effrontery of returning Viceroy Curzon's letters unread, goats being stolen from the people of Sikkim to which Britain provides its benevolent protection, trade with British India being hampered at every turn, and the Conventions of 1890 and 1893 all but being spat upon. As Peter Fleming (Ian's brother) wrote in Bayonets to Lhasa, the Tibetans' behaviour "was based four-square on infantile obstinacy."

Scene 5: Fruitless Negotiations with those bloody Tibetans

The British see their indomitable patience and tolerance tested to the ultimate extreme by Tibetan recalcitrance and tricky backsliding. Again they are unable to find a friendly, peaceful solution and discover to their dismay that only force is understood on the roof of the world. What makes this scene all the more haunting is the reunion of Austin and Don Grub, representing two completely different worlds but at heart indefatigable patriots.

Scene 6: At stately Pha Lha manor

Younghusband tries to communicate with the head of Pha Lha manor in order to obtain lodgings and provisions before his historic meeting with the Dalai Lama.

Scene 7: Yet More Fruitless Negotiation with Tibetans

The British continue to see their indomitable patience and tolerance tested to the extreme by Tibetan recalcitrance and tricky backsliding. Again they are unable to find a friendly, peaceful solution and discover to their dismay that only force is understood on the roof of the world.

Scene 8: The misunderstanding at Chumi Shengo

Part II

Scene 9: End of a Friendship

End to a remarkable friendship begins with savage violence and ends in a disturbing image of one looking wistfully at the other as he sleeps, thus changing the entire context of the film and covering it in ambiguity.

Scene 10: Under the stars with the General

Here after an imperial war council, I share a quiet word with General Macdonald in the darkness of a moonlit Tibetan forest.

Scene 11: No sex, please- we're Tibetans

The aged David Austin returns to his former haunts high in the Himalayas to hunt for his special lost friend from the past, Don Grub, who is shown in an obligatory romantic scene in which he appears to shun all contact with the weaker sex.

Scene 12: Yet more time-wasting with Tibetans

Another tedious round of negotiations with stubborn, intransigent Tibetans.

Scene 13: The strains show

Strains within Younghusband mission show between Younghusband and the head of the military forces intent on liberating the poor Tibetans from the nefarious Chinese.

Tibetans, who drink horrid butter tea and thus can ingest anything, are shown insulting the British by spilling out their tea. Given the past history of such insults dating from the Boston rebels, this obscene act demands a strong, resolute response.

Scene 14: The British being attacked by Tibetan thugs and suicide bombers

The Tibetan sneak attack of May 5, 1904 by reactionaries and the ruling class begins against Colonel Younghusband's peaceful, progressive mission in this thrilling scene from the epic 1904- The British Liberation of Tibet. Whilst Lt.Col. Brander is off with his force to Karo La, Younghusband and I are left vulnerable at our riverside camp at Changlo. In the second part I successfully run away from the Tibetans, while former student Michael Connolly dies for the first time in the film.

Scene 15: "Oh my God- The Stone-Throwers!"

Michael Connolly, as the only Caucasian member of the British army, is resurrected long enough to exclaim these immortal lines as British liberators murdered by terrorist suicide bombers on the roof of the world at Tsamdang (Red Idol) Gorge near Kala Tso salt lake. As Younghusband related in India and Tibet,

On the way to Gyantse, at the Tsamdang Gorge, the Tibetans again opposed our progress by building a wall across the narrow passage. But General Macdonald dislodged them and inflicted heavy loss, and on April 11 we arrived at Gyantse.Scene 16: Colonel Younghusband and David Austin share an intimate moment

In this touching scene involving a cartoon featuring a lion about to shoot a rabbit, Colonel Younghusband explains the humane concerns of the British Empire to see Tibet free, modern, and able at last to import Newcastle brown ale.

Scene 17: British battle for Nenying temple

British forces heroically battle against the Buddhist stronghold of Nenying, fanatically defended by some crazy woman with a long, very sharp sword. All I really do is stand on top of a hill and mutter "tsk tsk tsk... the humanity" as I struggle to understand why...

Scene 18: Soul-searching in a remote Tibetan temple

Scene of aching beauty as Younghusband and Austin encounter each other in the recesses of a Tibetan temple, each with conflicting thoughts and desperate dreams. Rather like that scene from On the Waterfront.

Scene 19: Yet MORE fruitless negotiations with Tibetans

This time the Chinese send their own emissary to sow dissension and pervert harmony for their own ends. I serve as interpreter to this devious mandarin.The roots of the 1959 invasion and subsequent anschluss lie here.

Scene 20: Murder on a roof on the roof of the world

More evidence of Tibetan barbarism as forces in the pay of Chinese imperialists brutally murder a pair of Indian soldiers without reason or warning. I can only stand by and watch, impotently, before wandering away to ponder the vicissitudes of bringing civilisation and modernity to the benighted races of the world.

Scene 21: No more negotiations

Tibetan intransigence and Chinese perfidy are forced to make way for British resolve.

Scene 22: The Battle of Gyantse

The

British initiate the opening rounds of the final battle before

finally being free to march on Lhasa and freeing Tibet once and for all

from Chinese intrigue with only a couple hundred soldiers, but not before a unique British soldier valiantly gets slain after standing up on top of an hill for all to see.

The battle

concludes with the good guys finally vanquishing all stubborn opposition

to modernity and development and liberate Tibet from Chinese control

and oppression for the next half century. Again former student Michael

Connolly (one of two Caucasians in the British army, and an Irishman to

boot) gets killed again; the number of times he gets killed in this film

outnumbers those of British Imperial forces who were killed during the

entire mission in reality.

Scene 23: Aftermath

Austin is left marvelling at the terrific success of the Mission, with Britain easily throwing off the yoke of Chinese oppression and freeing Tibet so that she can at last know the benefits of Anglobalisation, free trade, civilisation, and Newcastle brown ale.

Scene 24: Epilogue

With the Chinese pleading with Britain and America to save them from the Japanese running riot in their country and demanding self-determination for themselves, a grateful Don Grub finally understands the purpose of Younghusband's Mission forty years later and ends the film thanking Austin profusely for Tibet's liberation.

Behind the scenes