A short section devoted to my school- the Bavarian International School at schloss Haimhausen in kreis Dachau

In the district of Unterschleißheim is Lohhof, the nearest station to the Bavarian International School in Haimhausen where I work. The

population of Unterschleißheim itself exploded between 1933 when it had

753 inhabitants to 1939 with 1,737 inhabitants when the Nazis focused

on housing construction in Lohhof. In 1937 a forced labour camp was set

up in Lohhof near the train station to extract flax for the textile

industry, called "flax roasting", in which hundreds of French and Polish

women were used for forced labour. From 1941, Jewish women were also

deployed, whilst at the same time deportations began from the Lohhof

flax roastery until the camp was closed in 1942.

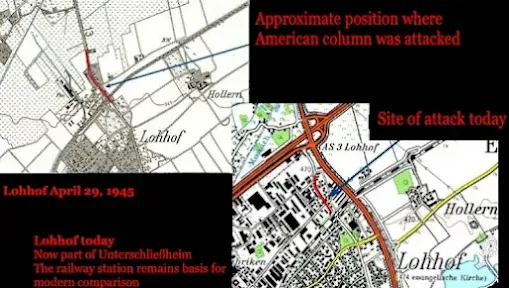

Behind the .50-calibre Machine Gunner on the Squad Halftrack from a series of photos by Sergeant C.O. Witt (HQ Platoon, B CO., 65th AIB) showing the American 20th Armoured Division leaving Haimhausen travelling towards Lohhof on April 2929, 1945. By this time at least two thousand members of the Waffen-ϟϟ and a last contingent of adolescent flak helpers and older men from the Volkssturm had gathered for the defence of Munich. A bloodbath awaited them all. First, several American tanks were destroyed. Flight support was denied to the units due to fresh snow and fog. Only by around 9.30 did infantrymen from the Rainbow Division, an elite unit, come to the rescue from Schleissheim airfield. Bulldozers simply rolled over the trenches, with numerous German defenders buried. The nearby barracks continued to fight hand to hand until 15.00. Besides Lohhof, the ϟϟ also resisted in Feldmoching, Freimann and Schleißheim. In Planegg, fanatical soldiers of the ϟϟ fought fiercely after the occupation. During the "Battle of Lohhof" about an hundred were killed, forty of whom were Americans..gif) On the left is the site of the assault then and now. Lohhof's subsequent growth after the war can be seen here in the GIF showing the site on November 1, 1943 and today. Everything

looked peaceful from the Maisteig on what is now the B 13 as white

flags fluttered in Lohhof. However, units of an ϟϟ army corps had taken

up positions in Lohhof at night, hiding in the bushes on the railway

embankment, in houses in Hollern and in the flax roast in

Unterschleissheim. When the Americans advanced, the German soldiers

first let two tanks pass, then opened fire on the crew trucks behind

them. The tanks were almost on Kreuzstrasse before they were forced to

react leading to a bitter struggle. The tanks fired and the American

soldiers crawled up to the occupied houses, threw petrol cans into them

and fired on them to set them on fire.

On the left is the site of the assault then and now. Lohhof's subsequent growth after the war can be seen here in the GIF showing the site on November 1, 1943 and today. Everything

looked peaceful from the Maisteig on what is now the B 13 as white

flags fluttered in Lohhof. However, units of an ϟϟ army corps had taken

up positions in Lohhof at night, hiding in the bushes on the railway

embankment, in houses in Hollern and in the flax roast in

Unterschleissheim. When the Americans advanced, the German soldiers

first let two tanks pass, then opened fire on the crew trucks behind

them. The tanks were almost on Kreuzstrasse before they were forced to

react leading to a bitter struggle. The tanks fired and the American

soldiers crawled up to the occupied houses, threw petrol cans into them

and fired on them to set them on fire.  The flax roast also burned and

the guesthouse beside the station ended up being badly damaged by

shelling. Whilst nearly on the German defenders were killed, on the

American side seven have been named, including the commander and his

driver along with forty dead and wounded. Apparently if the artillery

had not won the fight, aircraft would have been called to bomb

Unterschleissheim. As

it is, the fighting had continued into the early evening. The part of

the air base crew stationed in Unterschleissheim had surrendered without

a fight and were collected in the school yard for transport. The

Americans then searched the houses because they feared more ambushes.

Three young ϟϟ soldiers had fled and were hiding in the straw with a

farmer. The Americans stabbed the haystacks with pitchforks but didn't

find the three who were eventually rescued from the straw four days after the

Americans left - almost starved and thirsty.

The flax roast also burned and

the guesthouse beside the station ended up being badly damaged by

shelling. Whilst nearly on the German defenders were killed, on the

American side seven have been named, including the commander and his

driver along with forty dead and wounded. Apparently if the artillery

had not won the fight, aircraft would have been called to bomb

Unterschleissheim. As

it is, the fighting had continued into the early evening. The part of

the air base crew stationed in Unterschleissheim had surrendered without

a fight and were collected in the school yard for transport. The

Americans then searched the houses because they feared more ambushes.

Three young ϟϟ soldiers had fled and were hiding in the straw with a

farmer. The Americans stabbed the haystacks with pitchforks but didn't

find the three who were eventually rescued from the straw four days after the

Americans left - almost starved and thirsty.

.gif) The

Brauerei Gasthaus Lohhof today (where the wife and I first stayed when

we moved to Germany from China) and as it appeared April 29, 1945 with

the Americans after the battle for the town. On the right is how it

appeared three years later. Here the Americans celebrated their

victory and "decimated the beer stores", as Christoph says. The group

advanced to Munich meeting resistance, in Hochbrück, in Neuherberg.

Fighting raged on the tank meadow and around the ϟϟ barracks in

Freimann, the Americans lost tanks there alone, 70 of their soldiers

died, and several were wounded. On the afternoon of April 30, the day

Hitler committed suicide, resistance in the barracks was broken. Munich

was occupied from May 1. The Nazis were then picked up by the

Americans in Unterschleissheim, Pötsch reports and then taken to a

camp in Moosburg.

The

Brauerei Gasthaus Lohhof today (where the wife and I first stayed when

we moved to Germany from China) and as it appeared April 29, 1945 with

the Americans after the battle for the town. On the right is how it

appeared three years later. Here the Americans celebrated their

victory and "decimated the beer stores", as Christoph says. The group

advanced to Munich meeting resistance, in Hochbrück, in Neuherberg.

Fighting raged on the tank meadow and around the ϟϟ barracks in

Freimann, the Americans lost tanks there alone, 70 of their soldiers

died, and several were wounded. On the afternoon of April 30, the day

Hitler committed suicide, resistance in the barracks was broken. Munich

was occupied from May 1. The Nazis were then picked up by the

Americans in Unterschleissheim, Pötsch reports and then taken to a

camp in Moosburg.

.gif) Lohhof

was the site of a flax processing plant owned by the Lohhof Flax

Processing Company (Flachsröste Lohhof GmbH.) which was, in effect, a

forced labour camp. Located on what is now (possibly appropriately)

Siemensstraße, today it is the site of the refugee centre to which my

students at Bavarian International School visit as part of their service

commitments. Administratively, it was a satellite camp of Dachau. The

location was chosen due to its proximity to Munich and to the local

train station. The camp premises consisted of residential barracks,

barns, retting pits and an initial processing plant. The municipal

Aryanisation Department (Arisierungs-Dienststelle) of Munich instigated

and supervised the forced employment of three hundred Jews at the camp.

Among these, 110 were women and they worked at the plant; 68 of them

were sent from Lodz, and other women had to arrive each day from Munich,

primarily from the assembly site at the Berg am Laim monastery, and

return at night using trains and streetcars. Lohhof also served as an

assembly site where Jews from Munich were assembled prior to their

deportation. Additionally, during the war, over an hundred foreign workers from

Belgium, the Netherlands, France, Russia, Poland and the Ukraine were

employed at the plant. When the mass deportations of German Jews began in

November 1941, the Jewish workers were sent away from Lohhof to the

Milbertshofen camp, and from there they were deported to Kaunas,

Piaski, Theresienstadt, and Auschwitz. The last Jewish women

who worked at the camp were transferred on October 23, 1942, and were in

all likelihood deported to Auschwitz on May 18, 1943. During the last

few weeks of the war, the plant was damaged; afterwards, it was rebuilt.

Of the 300 Jews who worked at Lohhof, only thirty survived the war.

Lohhof

was the site of a flax processing plant owned by the Lohhof Flax

Processing Company (Flachsröste Lohhof GmbH.) which was, in effect, a

forced labour camp. Located on what is now (possibly appropriately)

Siemensstraße, today it is the site of the refugee centre to which my

students at Bavarian International School visit as part of their service

commitments. Administratively, it was a satellite camp of Dachau. The

location was chosen due to its proximity to Munich and to the local

train station. The camp premises consisted of residential barracks,

barns, retting pits and an initial processing plant. The municipal

Aryanisation Department (Arisierungs-Dienststelle) of Munich instigated

and supervised the forced employment of three hundred Jews at the camp.

Among these, 110 were women and they worked at the plant; 68 of them

were sent from Lodz, and other women had to arrive each day from Munich,

primarily from the assembly site at the Berg am Laim monastery, and

return at night using trains and streetcars. Lohhof also served as an

assembly site where Jews from Munich were assembled prior to their

deportation. Additionally, during the war, over an hundred foreign workers from

Belgium, the Netherlands, France, Russia, Poland and the Ukraine were

employed at the plant. When the mass deportations of German Jews began in

November 1941, the Jewish workers were sent away from Lohhof to the

Milbertshofen camp, and from there they were deported to Kaunas,

Piaski, Theresienstadt, and Auschwitz. The last Jewish women

who worked at the camp were transferred on October 23, 1942, and were in

all likelihood deported to Auschwitz on May 18, 1943. During the last

few weeks of the war, the plant was damaged; afterwards, it was rebuilt.

Of the 300 Jews who worked at Lohhof, only thirty survived the war.

Behind the .50-calibre Machine Gunner on the Squad Halftrack from a series of photos by Sergeant C.O. Witt (HQ Platoon, B CO., 65th AIB) showing the American 20th Armoured Division leaving Haimhausen travelling towards Lohhof on April 2929, 1945. By this time at least two thousand members of the Waffen-ϟϟ and a last contingent of adolescent flak helpers and older men from the Volkssturm had gathered for the defence of Munich. A bloodbath awaited them all. First, several American tanks were destroyed. Flight support was denied to the units due to fresh snow and fog. Only by around 9.30 did infantrymen from the Rainbow Division, an elite unit, come to the rescue from Schleissheim airfield. Bulldozers simply rolled over the trenches, with numerous German defenders buried. The nearby barracks continued to fight hand to hand until 15.00. Besides Lohhof, the ϟϟ also resisted in Feldmoching, Freimann and Schleißheim. In Planegg, fanatical soldiers of the ϟϟ fought fiercely after the occupation. During the "Battle of Lohhof" about an hundred were killed, forty of whom were Americans.

.gif) On the left is the site of the assault then and now. Lohhof's subsequent growth after the war can be seen here in the GIF showing the site on November 1, 1943 and today. Everything

looked peaceful from the Maisteig on what is now the B 13 as white

flags fluttered in Lohhof. However, units of an ϟϟ army corps had taken

up positions in Lohhof at night, hiding in the bushes on the railway

embankment, in houses in Hollern and in the flax roast in

Unterschleissheim. When the Americans advanced, the German soldiers

first let two tanks pass, then opened fire on the crew trucks behind

them. The tanks were almost on Kreuzstrasse before they were forced to

react leading to a bitter struggle. The tanks fired and the American

soldiers crawled up to the occupied houses, threw petrol cans into them

and fired on them to set them on fire.

On the left is the site of the assault then and now. Lohhof's subsequent growth after the war can be seen here in the GIF showing the site on November 1, 1943 and today. Everything

looked peaceful from the Maisteig on what is now the B 13 as white

flags fluttered in Lohhof. However, units of an ϟϟ army corps had taken

up positions in Lohhof at night, hiding in the bushes on the railway

embankment, in houses in Hollern and in the flax roast in

Unterschleissheim. When the Americans advanced, the German soldiers

first let two tanks pass, then opened fire on the crew trucks behind

them. The tanks were almost on Kreuzstrasse before they were forced to

react leading to a bitter struggle. The tanks fired and the American

soldiers crawled up to the occupied houses, threw petrol cans into them

and fired on them to set them on fire.  The flax roast also burned and

the guesthouse beside the station ended up being badly damaged by

shelling. Whilst nearly on the German defenders were killed, on the

American side seven have been named, including the commander and his

driver along with forty dead and wounded. Apparently if the artillery

had not won the fight, aircraft would have been called to bomb

Unterschleissheim. As

it is, the fighting had continued into the early evening. The part of

the air base crew stationed in Unterschleissheim had surrendered without

a fight and were collected in the school yard for transport. The

Americans then searched the houses because they feared more ambushes.

Three young ϟϟ soldiers had fled and were hiding in the straw with a

farmer. The Americans stabbed the haystacks with pitchforks but didn't

find the three who were eventually rescued from the straw four days after the

Americans left - almost starved and thirsty.

The flax roast also burned and

the guesthouse beside the station ended up being badly damaged by

shelling. Whilst nearly on the German defenders were killed, on the

American side seven have been named, including the commander and his

driver along with forty dead and wounded. Apparently if the artillery

had not won the fight, aircraft would have been called to bomb

Unterschleissheim. As

it is, the fighting had continued into the early evening. The part of

the air base crew stationed in Unterschleissheim had surrendered without

a fight and were collected in the school yard for transport. The

Americans then searched the houses because they feared more ambushes.

Three young ϟϟ soldiers had fled and were hiding in the straw with a

farmer. The Americans stabbed the haystacks with pitchforks but didn't

find the three who were eventually rescued from the straw four days after the

Americans left - almost starved and thirsty.

Much of the information and images for the Battle for Lohhof come from Rich Mintz and his remarkable Facebook group 20th Armoured Division in World War II.

The image on the left relates to colonel Newton W. Jones, Commander of

Combat Command B (CC-B), who was the first casualty in the ambush in

Lohhof, killed by a sniper as he led his troops whilst standing in his

Jeep. The photograph and caption is from 1st Lieutenant Felix E. Mock,

commander, 3rd Platoon, B CO, 65th AIB. That on the right is of 1st

Lieutenant Samuel F. Barnes of 2nd Platoon, B CO, 65th AIB (Task Force

20), who too was killed in action in a German ambush April 29, 1945. The

letter is the death notification to Mrs. Barnes from B CO. Commander,

CPT George Jared, 65th AIB.

.gif) The

Brauerei Gasthaus Lohhof today (where the wife and I first stayed when

we moved to Germany from China) and as it appeared April 29, 1945 with

the Americans after the battle for the town. On the right is how it

appeared three years later. Here the Americans celebrated their

victory and "decimated the beer stores", as Christoph says. The group

advanced to Munich meeting resistance, in Hochbrück, in Neuherberg.

Fighting raged on the tank meadow and around the ϟϟ barracks in

Freimann, the Americans lost tanks there alone, 70 of their soldiers

died, and several were wounded. On the afternoon of April 30, the day

Hitler committed suicide, resistance in the barracks was broken. Munich

was occupied from May 1. The Nazis were then picked up by the

Americans in Unterschleissheim, Pötsch reports and then taken to a

camp in Moosburg.

The

Brauerei Gasthaus Lohhof today (where the wife and I first stayed when

we moved to Germany from China) and as it appeared April 29, 1945 with

the Americans after the battle for the town. On the right is how it

appeared three years later. Here the Americans celebrated their

victory and "decimated the beer stores", as Christoph says. The group

advanced to Munich meeting resistance, in Hochbrück, in Neuherberg.

Fighting raged on the tank meadow and around the ϟϟ barracks in

Freimann, the Americans lost tanks there alone, 70 of their soldiers

died, and several were wounded. On the afternoon of April 30, the day

Hitler committed suicide, resistance in the barracks was broken. Munich

was occupied from May 1. The Nazis were then picked up by the

Americans in Unterschleissheim, Pötsch reports and then taken to a

camp in Moosburg..gif) Lohhof

was the site of a flax processing plant owned by the Lohhof Flax

Processing Company (Flachsröste Lohhof GmbH.) which was, in effect, a

forced labour camp. Located on what is now (possibly appropriately)

Siemensstraße, today it is the site of the refugee centre to which my

students at Bavarian International School visit as part of their service

commitments. Administratively, it was a satellite camp of Dachau. The

location was chosen due to its proximity to Munich and to the local

train station. The camp premises consisted of residential barracks,

barns, retting pits and an initial processing plant. The municipal

Aryanisation Department (Arisierungs-Dienststelle) of Munich instigated

and supervised the forced employment of three hundred Jews at the camp.

Among these, 110 were women and they worked at the plant; 68 of them

were sent from Lodz, and other women had to arrive each day from Munich,

primarily from the assembly site at the Berg am Laim monastery, and

return at night using trains and streetcars. Lohhof also served as an

assembly site where Jews from Munich were assembled prior to their

deportation. Additionally, during the war, over an hundred foreign workers from

Belgium, the Netherlands, France, Russia, Poland and the Ukraine were

employed at the plant. When the mass deportations of German Jews began in

November 1941, the Jewish workers were sent away from Lohhof to the

Milbertshofen camp, and from there they were deported to Kaunas,

Piaski, Theresienstadt, and Auschwitz. The last Jewish women

who worked at the camp were transferred on October 23, 1942, and were in

all likelihood deported to Auschwitz on May 18, 1943. During the last

few weeks of the war, the plant was damaged; afterwards, it was rebuilt.

Of the 300 Jews who worked at Lohhof, only thirty survived the war.

Lohhof

was the site of a flax processing plant owned by the Lohhof Flax

Processing Company (Flachsröste Lohhof GmbH.) which was, in effect, a

forced labour camp. Located on what is now (possibly appropriately)

Siemensstraße, today it is the site of the refugee centre to which my

students at Bavarian International School visit as part of their service

commitments. Administratively, it was a satellite camp of Dachau. The

location was chosen due to its proximity to Munich and to the local

train station. The camp premises consisted of residential barracks,

barns, retting pits and an initial processing plant. The municipal

Aryanisation Department (Arisierungs-Dienststelle) of Munich instigated

and supervised the forced employment of three hundred Jews at the camp.

Among these, 110 were women and they worked at the plant; 68 of them

were sent from Lodz, and other women had to arrive each day from Munich,

primarily from the assembly site at the Berg am Laim monastery, and

return at night using trains and streetcars. Lohhof also served as an

assembly site where Jews from Munich were assembled prior to their

deportation. Additionally, during the war, over an hundred foreign workers from

Belgium, the Netherlands, France, Russia, Poland and the Ukraine were

employed at the plant. When the mass deportations of German Jews began in

November 1941, the Jewish workers were sent away from Lohhof to the

Milbertshofen camp, and from there they were deported to Kaunas,

Piaski, Theresienstadt, and Auschwitz. The last Jewish women

who worked at the camp were transferred on October 23, 1942, and were in

all likelihood deported to Auschwitz on May 18, 1943. During the last

few weeks of the war, the plant was damaged; afterwards, it was rebuilt.

Of the 300 Jews who worked at Lohhof, only thirty survived the war. Max Strnad has researched the camps for Jews in Munich in some detail. A special case there was the Lohhof Jewish Labour Detachment (Jüdisches Arbeitskommando). The Lohhof camp was established in June 1941 on the orders of the Munich Aryanization Authority (Arisierungsstelle), a radical antisemitic office of the Munich/Upper Bavarian Regional Headquarters (Gauleitung) of the Nazi Party. This was the third residential and work camp for Jews established in Munich, after the Milbertshofen "Jewish Settlement" (Judensiedlung) and the Berg am Laim "Home Facility" (Heimanlage). The Aryanisation Authority set up this camp system in 1941, as a multipurpose instrument of terror against the Jewish population. The camps served, apart from their central function of forced labor, to remove Jews from rental accommodation and put them into separate Jewish residences, for better supervision and also to assemble them ready for deportation. In Lohhof, mainly Jewish women between fourteen and forty-five years old were deployed there in June 1941, but later much older Jewish women and men were included. Until the fall of 1942, about 250 Jews were employed there altogether. The Jewish work force numbered on average about 110 people. Some seventy women were accommodated in barracks on the factory grounds, while the remainder had to travel daily from Munich. After Gauleiter Adolf Wagner's decree forbidding the use of trams by Jews in September 1941, the daily trip to Unterschleissheim became an exhausting journey lasting several hours. On November 20, 1941, sixty-three people, comprising more than half of the Jewish forced labourers, were deported to Kaunas in Lithuania. In the middle of December 1941, the Lohhof Flachsröste was sent sixty-eight young Jewish women, who had been working on other flax-roasting farms in Bavaria for several months, but who all originally came from the Łódź (Litzmannstadt) ghetto. These Polish Jewish women remained in Lohhof until the fall of 1942, when they were transferred to Augsburg, where they stayed as a group in another camp, before being deported to Auschwitz in 1943.

Simone Gigliotti, Hilary Earl (268) A Companion to the Holocaust

Schloss Haimhausen in a turn of the century postcard and today

Schloss Haimhausen's story begins in the mediæval period, with its first documented mention in 1281 when it was listed as a castle (castrum) in a gazetteer

of Upper Bavaria. This

initial structure, likely a fortified building, was emblematic of the

era's architectural style, designed for defence in a period marked by

local conflicts and power struggles. The early history of Schloss

Haimhausen is reflective of the broader feudal structures prevalent in

Bavaria during this time. The impact of the Thirty Years' War on Schloss Haimhausen and the surrounding region was

profound. This period, one of the most devastating in European history,

saw widespread destruction and upheaval. The original structure of

Schloss Haimhausen didn't survive the war and was left in ruins and the

war's effect on the region's architecture and society was significant,

leading to a period of rebuilding and transformation across Bavaria. In

1660, a pivotal moment in the history of Schloss Haimhausen occurred.

Andreas Wolff, a notable figure of the time, undertook the

reconstruction of the Schloss, choosing to rebuild it as an ornate

Baroque structure. This decision marked a significant departure from the

original medieval fortress, reflecting the changing architectural and

cultural trends of the era. Wolff's reconstruction of Schloss Haimhausen

is indicative of the broader shift in European architecture towards the

Baroque style, characterized by grandeur, drama, and richness in

design. The work of François Cuvilliés the Elder in 1747 further

transformed Schloss Haimhausen. Cuvilliés, renowned for his

contributions to Bavarian Rococo architecture, expanded the villa,

adding seven bays on each side and two wings.

Schloss Haimhausen's story begins in the mediæval period, with its first documented mention in 1281 when it was listed as a castle (castrum) in a gazetteer

of Upper Bavaria. This

initial structure, likely a fortified building, was emblematic of the

era's architectural style, designed for defence in a period marked by

local conflicts and power struggles. The early history of Schloss

Haimhausen is reflective of the broader feudal structures prevalent in

Bavaria during this time. The impact of the Thirty Years' War on Schloss Haimhausen and the surrounding region was

profound. This period, one of the most devastating in European history,

saw widespread destruction and upheaval. The original structure of

Schloss Haimhausen didn't survive the war and was left in ruins and the

war's effect on the region's architecture and society was significant,

leading to a period of rebuilding and transformation across Bavaria. In

1660, a pivotal moment in the history of Schloss Haimhausen occurred.

Andreas Wolff, a notable figure of the time, undertook the

reconstruction of the Schloss, choosing to rebuild it as an ornate

Baroque structure. This decision marked a significant departure from the

original medieval fortress, reflecting the changing architectural and

cultural trends of the era. Wolff's reconstruction of Schloss Haimhausen

is indicative of the broader shift in European architecture towards the

Baroque style, characterized by grandeur, drama, and richness in

design. The work of François Cuvilliés the Elder in 1747 further

transformed Schloss Haimhausen. Cuvilliés, renowned for his

contributions to Bavarian Rococo architecture, expanded the villa,

adding seven bays on each side and two wings. .gif) His work on Schloss

Haimhausen is particularly notable for its high roof, typical of the

region, a feature that has remained unchanged to this day. Cuvilliés'

influence extended beyond Haimhausen, with his notable works including

the Munich Residenz and the Amalienburg in the grounds of Schloss

Nymphenburg. The

ceiling murals in both the Golden Room and the Chapel, executed by

Johann Bergmüller in 1750, are another significant aspect of the

Schloss's architectural evolution. Bergmüller, a famous Augsburg artist,

brought a unique artistic flair to the Schloss, his work reflecting the

rich artistic traditions of the period. The architectural evolution of

Schloss Haimhausen, from its initial construction in the medieval

period to its Baroque and Rococo transformations, mirrors the broader

historical and cultural shifts in Bavaria and Germany. Each phase of its

development reflects the changing tastes, requirements, and artistic

trends of the times, as well as the shifting social, political, and

cultural landscapes.

His work on Schloss

Haimhausen is particularly notable for its high roof, typical of the

region, a feature that has remained unchanged to this day. Cuvilliés'

influence extended beyond Haimhausen, with his notable works including

the Munich Residenz and the Amalienburg in the grounds of Schloss

Nymphenburg. The

ceiling murals in both the Golden Room and the Chapel, executed by

Johann Bergmüller in 1750, are another significant aspect of the

Schloss's architectural evolution. Bergmüller, a famous Augsburg artist,

brought a unique artistic flair to the Schloss, his work reflecting the

rich artistic traditions of the period. The architectural evolution of

Schloss Haimhausen, from its initial construction in the medieval

period to its Baroque and Rococo transformations, mirrors the broader

historical and cultural shifts in Bavaria and Germany. Each phase of its

development reflects the changing tastes, requirements, and artistic

trends of the times, as well as the shifting social, political, and

cultural landscapes..gif) The

noble family of Haimhausen, who owned the Schloss at this time,

initiated extensive renovations and expansions. These changes included

the addition of ornamental gardens and the enhancement of living

quarters, reflecting the Renaissance's emphasis on aesthetics, humanism,

and the rediscovery of classical antiquity. The impact of the Thirty

Years' War on Schloss Haimhausen and the surrounding region was

profound. During this tumultuous period, many structures, including

manor houses and castles, were damaged or destroyed. However, Schloss

Haimhausen not only survived but also underwent further modifications in

the post-war period. This resilience and adaptation are emblematic of

the broader historical narrative of Bavaria during the Thirty Years'

War, where despite immense destruction, there was a concerted effort

towards rebuilding and restoration. In the 18th century, the Schloss

witnessed another significant phase of transformation under the

influence of Baroque and Rococo styles.

The

noble family of Haimhausen, who owned the Schloss at this time,

initiated extensive renovations and expansions. These changes included

the addition of ornamental gardens and the enhancement of living

quarters, reflecting the Renaissance's emphasis on aesthetics, humanism,

and the rediscovery of classical antiquity. The impact of the Thirty

Years' War on Schloss Haimhausen and the surrounding region was

profound. During this tumultuous period, many structures, including

manor houses and castles, were damaged or destroyed. However, Schloss

Haimhausen not only survived but also underwent further modifications in

the post-war period. This resilience and adaptation are emblematic of

the broader historical narrative of Bavaria during the Thirty Years'

War, where despite immense destruction, there was a concerted effort

towards rebuilding and restoration. In the 18th century, the Schloss

witnessed another significant phase of transformation under the

influence of Baroque and Rococo styles. .gif) This era, known for its ornate

and elaborate artistic expressions, saw the Schloss's façade being

redesigned and the interiors richly decorated. The grand staircase and

the main hall, adorned with frescoes and intricate stucco work, were

products of this period. These architectural elements are not just

decorative but also symbolic of the era's artistic and cultural ethos,

characterised by grandeur, opulence, and a strong emphasis on visual

appeal. The architectural evolution of Schloss Haimhausen is a

reflection of the broader historical and cultural shifts in Bavaria and

Germany. Each phase of its development, from a mediæval fortress to a

Renaissance château and later to a Baroque and Rococo masterpiece,

mirrors the changing tastes, requirements, and artistic trends of the

times. This evolution is not merely a matter of aesthetic change but

also indicative of the shifting social, political, and cultural

landscapes.

This era, known for its ornate

and elaborate artistic expressions, saw the Schloss's façade being

redesigned and the interiors richly decorated. The grand staircase and

the main hall, adorned with frescoes and intricate stucco work, were

products of this period. These architectural elements are not just

decorative but also symbolic of the era's artistic and cultural ethos,

characterised by grandeur, opulence, and a strong emphasis on visual

appeal. The architectural evolution of Schloss Haimhausen is a

reflection of the broader historical and cultural shifts in Bavaria and

Germany. Each phase of its development, from a mediæval fortress to a

Renaissance château and later to a Baroque and Rococo masterpiece,

mirrors the changing tastes, requirements, and artistic trends of the

times. This evolution is not merely a matter of aesthetic change but

also indicative of the shifting social, political, and cultural

landscapes.

Haimhausen

schloss became the property of the family Butler v. Clonebough, after

having been awarded to the Irish officer Walther Butler (known as the

"Wallenstein murderer") in thanks for his fulfilling a contract to

deliver Wallenstein "dead or alive" on February 25, 1634. Friedrich

Schiller immortalised Wallenstein in the dramatic trilogy that bears his

name (completed in 1799). He did not enjoy his success for long,

passing away in 1635 after being wounded. The schloss was rebuilt in

1660 after a fire in the Thirty Years' War and has been expanded ever

since. Under Reichsgraf Karl Ferdinand Maria von und zu Haimhausen, from

1743 to 1749 a major renovation was carried out by François de

Cuvilliés the Elder. Since then, the late baroque chapel Salvator Mundi

with stucco work and altars by the Flemish artist Egid Verhelst and his

sons and the ceiling painting by Johann Georg Bergmüller, which was made

in 1750, has been a special gem within the castle. The

property was then passed from generation up until Theobald, who had a

close relationship to Count Stauffenberg. Theobald, the last heir to the

Butler von Clonebough line, was born

in Shanghai on July 15, 1899. His father Arthur died when Theobald was

not yet five years old. He was sent to Munich, he became a lieutenant in

1918 and studied mechanical engineering, where he also did his

doctorate. In 1937 he married Irene Rosewsky in Riga with whom he had

four children, one of whom died in 1941. The family lived in

Neubrandenburg, north of Berlin. During the Second World War, Theobald

had an important position in the armaments industry and by 1943 he lived

alone in Kempten in the Allgäu. As early as 1944, he is said to have

repeatedly urged his wife to move away from Neubrandenburg to join him

in Kempten which was not allowed by the local Nazi district leader. In

March 1945 Theobald left Kempten by car in an attempt to save his wife

and children from the approaching Soviet troops. In the end he is said

to have poisoned his wife and three children on April 29, 1945, then set

the house on fire before shooting himself. So ended the line of the

Counts of v. Clonebough gen. Haimhausen on April 29, 1945.

In front of the Golden Room and inside today. This banqueting hall, with its ceiling painting of The Four Seasons by Bergmuller (dated

1750) and its two rare Nymphenburger porcelain stoves, forms the visual climax

of the state apartments of schloss Haimhausen.

In his May 6, 1945 sermon, the local Ottershausen priest spoke of how "God has helped us up to this point". Thus far the damage caused by the war in Haimhausen and the area around was only minimal. Despite the proximity of the Schleissheim airfield, only a few windows in the Ottershausen church were broken by air raids. Bombs repeatedly fell on the parish fields, but never on a village. On Sunday, April 29, the day the Americans invaded, no church service could be held. From early in the morning, the start of fighting was to be expected at any moment. At around ten in the morning the first American grenades fell on the parish village but there was no major damage to buildings. In Inhausen, a grenade hit the sexton's stable the day before, killing several animals. A grenade exploded in the new cemetery in Haimhausen. Several gravestones were more or less damaged. Another grenade fell into the rectory garden. A number of fruit trees were damaged and about 15 windows were broken in the rectory but the church remained undamaged, right next to the rectory. During the bombardment, the German defence retreated south into the forest between Haimhausen, Inhausen and Ottershausen. Fifteen minutes after the bombardment, the first American reconnaissance troop arrived in the village.

Showing the balcony erected in front of the chapel for owner Haniel's wife who had suffered an accident shown in 1939

Bavarian International School's chapel before the war and now. It owes its splendour to its ceiling painting, again by Bergmuller- the Salvator Mundi,

dated 1750- as well as the delicate Rococo stucco work by Verhelst. The

chapel is located in the south wing and is remarkably spacious for its

purpose. In shape it is a simple, flat-roofed rectangular hall, but the

chapel only derives its effect from its rich furnishings. The

construction and furnishings date from the time of Cuvilliés' castle

expansion from 1747. The central parts of the furnishings - altar

structures, pulpit, confessionals, stucco - were created by the

Verhelsts. The builder Karl Joseph Maria Reichsgraf von und zu

Haimhausen is commemorated by his epitaph on the southern inner wall of

the chapel; the inscription praises the integrity of the deceased and

his good Christian care towards his subjects. The chapel bears the

patronage of St. Salvator, which was taken over from several previous

chapels in the old palace complex that were attested one after the

other. The ceiling fresco and the high altar refer to this, the excerpt

of which shows sculptural representations of Christ carrying the cross

and the Arma Christi and in the centre of which is an older Christ with

the flag, created around 1680-1690. Both side altars have altarpieces by

Johann Georg Bergmüller, which he probably painted in the winter of

1748-49. The picture on the left altar has the signature “JGB 1749” at

the bottom left. The themes of both images refer to church festivals

that were modern at the time with the festival of the Marriage of Mary

introduced in 1725 and John of Nepomuk, canonised in 1729. However, according to one source, Bergmüller's

numerous altarpieces are inferior in artistic value to his frescoes.

They contain a variety of borrowings from the type treasure of the time;

as compositions they are usually cleverly arranged, but they are not

convincing as a creative idea. The skillful and safe treatment of the

human body suggests a thorough study of anatomy. His work as a fresco

painter developed more freely and effectively. Without being one of the

pioneering talents, his talent and solid skills provided him with a

wealth of important commissions, including, above all, the churches in

Dießen, Ochsenhause and Steingaden.

Directly above is this fascinating representation of the return of Christ on the throne 0f the Trinity; the largest Salvator Mundi of its kind

in which God holds the Flaming Sword of Judgement and has the left hand

on the empty seat to his right whilst in the centre a kneeling Christ

with the cross rises over a world in flames, depicting the four

continents known at that time. But what makes this painting remarkable

is the representation of the Holy Spirit in human form. This is

expressly forbidden by the Catholic Church, as Pope Benedict XIV

declared in October 1745 just before this painting was created, and and

today is only permitted in the form of a dove. As a Catholic colleague

remarked upon entering, "God is not present," noting the lack of a

sanctuary lamp.

On the right is a close-up during the 650,000 euro renovation of the chapel completed in 2010. An interesting touch on the ceiling is the expulsion from Paradise on the right, showing Adam and Eve being followed by a dog and snake hopping along, and at the other end above the altar Christ on the Mount of Olives, with the snake making a reappearance with apple in mouth.

The

Bavarian State Library in Munich on Ludwigstrasse, shown after the

wartime bombing and today. A beacon of cultural and historical

preservation, the library faced a daunting challenge with the onset of

the Second World War. Before the war, the Bavarian State Library,

established in 1558, was renowned for its extensive collection of

manuscripts, rare books, and scholarly works. It held manuscripts from

the Carolingian era, first editions from the Renaissance, and documents

pivotal to European intellectual history. With the growing threat of war

in the late 1930s, the library's director, Dr. Gustav Hofmann, foresaw

the potential destruction of these irreplaceable treasures. Under his

guidance, the library undertook a comprehensive cataloguing and

prioritisation process. This meticulous effort aimed to identify items

of irreplaceable value and historical significance. Manuscripts,

incunabula, and rare books were earmarked for relocation, a task

demanding discretion and urgency. The relocation strategy involved

selecting both local and distant sites for storage. By the time of the 1944 bombing, the library's collection was distributed throughout 28 sites in Oberbayern. Schloss

Haimhausen was chosen for its strategic location, offering relative

safety from the anticipated aerial bombardments targeting major cities.

The

Bavarian State Library in Munich on Ludwigstrasse, shown after the

wartime bombing and today. A beacon of cultural and historical

preservation, the library faced a daunting challenge with the onset of

the Second World War. Before the war, the Bavarian State Library,

established in 1558, was renowned for its extensive collection of

manuscripts, rare books, and scholarly works. It held manuscripts from

the Carolingian era, first editions from the Renaissance, and documents

pivotal to European intellectual history. With the growing threat of war

in the late 1930s, the library's director, Dr. Gustav Hofmann, foresaw

the potential destruction of these irreplaceable treasures. Under his

guidance, the library undertook a comprehensive cataloguing and

prioritisation process. This meticulous effort aimed to identify items

of irreplaceable value and historical significance. Manuscripts,

incunabula, and rare books were earmarked for relocation, a task

demanding discretion and urgency. The relocation strategy involved

selecting both local and distant sites for storage. By the time of the 1944 bombing, the library's collection was distributed throughout 28 sites in Oberbayern. Schloss

Haimhausen was chosen for its strategic location, offering relative

safety from the anticipated aerial bombardments targeting major cities.

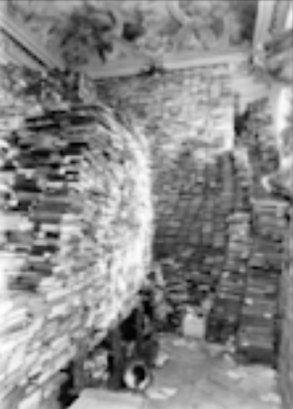

%20(1).gif) The photos here date from 1949

and show the thousands of books from the Bayerischen Staatsbibliothek

that were stored for safety in the Haimhauser Schlosskapelle in today's

Bavarian International School. The

transportation of the library's treasures to Schloss Haimhausen was

executed with utmost secrecy. Items were moved under the cover of

darkness in unmarked vehicles. This operation was governed by a

directive issued by Dr. Hofmann in early 1940, which outlined the

procedures for the safe transport and storage of the library's most

valuable items. The directive emphasised the need for speed and secrecy,

acknowledging the advancing threat of aerial raids on Munich.

The photos here date from 1949

and show the thousands of books from the Bayerischen Staatsbibliothek

that were stored for safety in the Haimhauser Schlosskapelle in today's

Bavarian International School. The

transportation of the library's treasures to Schloss Haimhausen was

executed with utmost secrecy. Items were moved under the cover of

darkness in unmarked vehicles. This operation was governed by a

directive issued by Dr. Hofmann in early 1940, which outlined the

procedures for the safe transport and storage of the library's most

valuable items. The directive emphasised the need for speed and secrecy,

acknowledging the advancing threat of aerial raids on Munich.

The logistical challenges of moving and storing the library's collection were immense. Dr. Hofmann and his team had to ensure the safety of items that were not only physically delicate but also of immense historical value. The transportation process was fraught with risks, including potential damage from handling, environmental factors, and the ever-present threat of discovery by enemy forces.

In addition to the physical transportation, Dr. Hofmann had to navigate the complex political landscape of the time. He was acutely aware of the Nazi regime's interest in cultural artefacts, especially those of significant historical and ideological value. This added a layer of complexity to the operation, as he had to balance the need for secrecy with the demands and scrutiny of the regime.

The

choice of Schloss Haimhausen as a storage site was strategic. Its

location away from major urban centres reduced the risk of damage from

air raids. Moreover, the structure of the Schloss, with its spacious

rooms and stable environmental conditions, provided an ideal setting for

the preservation of delicate manuscripts and books. Upon the successful

transportation of the items to Schloss Haimhausen, the next challenge

was their preservation and protection in situ. Hofmann implemented

strict protocols for the handling and storage of the items. These

protocols were designed to mitigate the risks of environmental damage,

such as humidity and temperature fluctuations, which could be

detrimental to the fragile manuscripts and books. The staff at Schloss

Haimhausen, under the guidance of Hofmann, maintained meticulous records

of the items stored, their condition, and their exact location within

the Schloss. This level of detail was crucial not only for the immediate

preservation of the collection but also for its eventual return to the

library post-war.

The

choice of Schloss Haimhausen as a storage site was strategic. Its

location away from major urban centres reduced the risk of damage from

air raids. Moreover, the structure of the Schloss, with its spacious

rooms and stable environmental conditions, provided an ideal setting for

the preservation of delicate manuscripts and books. Upon the successful

transportation of the items to Schloss Haimhausen, the next challenge

was their preservation and protection in situ. Hofmann implemented

strict protocols for the handling and storage of the items. These

protocols were designed to mitigate the risks of environmental damage,

such as humidity and temperature fluctuations, which could be

detrimental to the fragile manuscripts and books. The staff at Schloss

Haimhausen, under the guidance of Hofmann, maintained meticulous records

of the items stored, their condition, and their exact location within

the Schloss. This level of detail was crucial not only for the immediate

preservation of the collection but also for its eventual return to the

library post-war.

On the right is a close-up during the 650,000 euro renovation of the chapel completed in 2010. An interesting touch on the ceiling is the expulsion from Paradise on the right, showing Adam and Eve being followed by a dog and snake hopping along, and at the other end above the altar Christ on the Mount of Olives, with the snake making a reappearance with apple in mouth.

The

Bavarian State Library in Munich on Ludwigstrasse, shown after the

wartime bombing and today. A beacon of cultural and historical

preservation, the library faced a daunting challenge with the onset of

the Second World War. Before the war, the Bavarian State Library,

established in 1558, was renowned for its extensive collection of

manuscripts, rare books, and scholarly works. It held manuscripts from

the Carolingian era, first editions from the Renaissance, and documents

pivotal to European intellectual history. With the growing threat of war

in the late 1930s, the library's director, Dr. Gustav Hofmann, foresaw

the potential destruction of these irreplaceable treasures. Under his

guidance, the library undertook a comprehensive cataloguing and

prioritisation process. This meticulous effort aimed to identify items

of irreplaceable value and historical significance. Manuscripts,

incunabula, and rare books were earmarked for relocation, a task

demanding discretion and urgency. The relocation strategy involved

selecting both local and distant sites for storage. By the time of the 1944 bombing, the library's collection was distributed throughout 28 sites in Oberbayern. Schloss

Haimhausen was chosen for its strategic location, offering relative

safety from the anticipated aerial bombardments targeting major cities.

The

Bavarian State Library in Munich on Ludwigstrasse, shown after the

wartime bombing and today. A beacon of cultural and historical

preservation, the library faced a daunting challenge with the onset of

the Second World War. Before the war, the Bavarian State Library,

established in 1558, was renowned for its extensive collection of

manuscripts, rare books, and scholarly works. It held manuscripts from

the Carolingian era, first editions from the Renaissance, and documents

pivotal to European intellectual history. With the growing threat of war

in the late 1930s, the library's director, Dr. Gustav Hofmann, foresaw

the potential destruction of these irreplaceable treasures. Under his

guidance, the library undertook a comprehensive cataloguing and

prioritisation process. This meticulous effort aimed to identify items

of irreplaceable value and historical significance. Manuscripts,

incunabula, and rare books were earmarked for relocation, a task

demanding discretion and urgency. The relocation strategy involved

selecting both local and distant sites for storage. By the time of the 1944 bombing, the library's collection was distributed throughout 28 sites in Oberbayern. Schloss

Haimhausen was chosen for its strategic location, offering relative

safety from the anticipated aerial bombardments targeting major cities.%20(1).gif) The photos here date from 1949

and show the thousands of books from the Bayerischen Staatsbibliothek

that were stored for safety in the Haimhauser Schlosskapelle in today's

Bavarian International School. The

transportation of the library's treasures to Schloss Haimhausen was

executed with utmost secrecy. Items were moved under the cover of

darkness in unmarked vehicles. This operation was governed by a

directive issued by Dr. Hofmann in early 1940, which outlined the

procedures for the safe transport and storage of the library's most

valuable items. The directive emphasised the need for speed and secrecy,

acknowledging the advancing threat of aerial raids on Munich.

The photos here date from 1949

and show the thousands of books from the Bayerischen Staatsbibliothek

that were stored for safety in the Haimhauser Schlosskapelle in today's

Bavarian International School. The

transportation of the library's treasures to Schloss Haimhausen was

executed with utmost secrecy. Items were moved under the cover of

darkness in unmarked vehicles. This operation was governed by a

directive issued by Dr. Hofmann in early 1940, which outlined the

procedures for the safe transport and storage of the library's most

valuable items. The directive emphasised the need for speed and secrecy,

acknowledging the advancing threat of aerial raids on Munich.The logistical challenges of moving and storing the library's collection were immense. Dr. Hofmann and his team had to ensure the safety of items that were not only physically delicate but also of immense historical value. The transportation process was fraught with risks, including potential damage from handling, environmental factors, and the ever-present threat of discovery by enemy forces.

In addition to the physical transportation, Dr. Hofmann had to navigate the complex political landscape of the time. He was acutely aware of the Nazi regime's interest in cultural artefacts, especially those of significant historical and ideological value. This added a layer of complexity to the operation, as he had to balance the need for secrecy with the demands and scrutiny of the regime.

The

choice of Schloss Haimhausen as a storage site was strategic. Its

location away from major urban centres reduced the risk of damage from

air raids. Moreover, the structure of the Schloss, with its spacious

rooms and stable environmental conditions, provided an ideal setting for

the preservation of delicate manuscripts and books. Upon the successful

transportation of the items to Schloss Haimhausen, the next challenge

was their preservation and protection in situ. Hofmann implemented

strict protocols for the handling and storage of the items. These

protocols were designed to mitigate the risks of environmental damage,

such as humidity and temperature fluctuations, which could be

detrimental to the fragile manuscripts and books. The staff at Schloss

Haimhausen, under the guidance of Hofmann, maintained meticulous records

of the items stored, their condition, and their exact location within

the Schloss. This level of detail was crucial not only for the immediate

preservation of the collection but also for its eventual return to the

library post-war.

The

choice of Schloss Haimhausen as a storage site was strategic. Its

location away from major urban centres reduced the risk of damage from

air raids. Moreover, the structure of the Schloss, with its spacious

rooms and stable environmental conditions, provided an ideal setting for

the preservation of delicate manuscripts and books. Upon the successful

transportation of the items to Schloss Haimhausen, the next challenge

was their preservation and protection in situ. Hofmann implemented

strict protocols for the handling and storage of the items. These

protocols were designed to mitigate the risks of environmental damage,

such as humidity and temperature fluctuations, which could be

detrimental to the fragile manuscripts and books. The staff at Schloss

Haimhausen, under the guidance of Hofmann, maintained meticulous records

of the items stored, their condition, and their exact location within

the Schloss. This level of detail was crucial not only for the immediate

preservation of the collection but also for its eventual return to the

library post-war.The

war years brought unprecedented challenges to Schloss Haimhausen,

transforming it from a mere repository into a bastion safeguarding

Bavaria's cultural heritage. The Nazi regime's policies towards cultural

artifacts, especially those of significant historical and ideological

value, posed a constant threat. Dr. Hofmann and his team had to navigate

these treacherous waters, balancing the preservation of the library's

collection with the regime's increasing interference. The Nazi regime

was engaged in a systematic campaign to appropriate cultural artifacts

for ideological propaganda or personal gain.  This

put the collection at Schloss Haimhausen at risk of confiscation or

destruction. Dr. Hofmann, therefore, had to employ a combination of

diplomatic tact and subterfuge to keep the collection safe. One

strategy employed by Dr. Hofmann was to obscure the true value of the

collection. He would often downplay the significance of certain items or

mislabel them to avoid attracting attention from the regime's

officials. This tactic was risky but necessary to ensure the safety of

the collection.

This

put the collection at Schloss Haimhausen at risk of confiscation or

destruction. Dr. Hofmann, therefore, had to employ a combination of

diplomatic tact and subterfuge to keep the collection safe. One

strategy employed by Dr. Hofmann was to obscure the true value of the

collection. He would often downplay the significance of certain items or

mislabel them to avoid attracting attention from the regime's

officials. This tactic was risky but necessary to ensure the safety of

the collection.

This

put the collection at Schloss Haimhausen at risk of confiscation or

destruction. Dr. Hofmann, therefore, had to employ a combination of

diplomatic tact and subterfuge to keep the collection safe. One

strategy employed by Dr. Hofmann was to obscure the true value of the

collection. He would often downplay the significance of certain items or

mislabel them to avoid attracting attention from the regime's

officials. This tactic was risky but necessary to ensure the safety of

the collection.

This

put the collection at Schloss Haimhausen at risk of confiscation or

destruction. Dr. Hofmann, therefore, had to employ a combination of

diplomatic tact and subterfuge to keep the collection safe. One

strategy employed by Dr. Hofmann was to obscure the true value of the

collection. He would often downplay the significance of certain items or

mislabel them to avoid attracting attention from the regime's

officials. This tactic was risky but necessary to ensure the safety of

the collection.In

the latter years of the war, Schloss Haimhausen faced its most severe

challenges. The advancing Allied forces, particularly the American

troops, posed a new set of risks to the collection. The Schloss, like

many other historic sites in Germany, was at risk of being caught in the

crossfire or being requisitioned by the occupying forces.

Dr. Hofmann's foresight in the early years of the war proved invaluable during this period. He had established a network of contacts within the local community and among various military personnel, which he leveraged to negotiate the Schloss's safety. His diplomatic skills were crucial in ensuring that the Schloss was not used as a military base or subjected to unnecessary destruction.

Moreover,

the staff at Schloss Haimhausen played a pivotal role in liaising with

the American troops. They provided crucial information about the

cultural and historical significance of the Schloss and its contents,

persuading the troops to spare it from harm. This interaction

highlighted the importance of cultural diplomacy during times of

conflict.

Moreover,

the staff at Schloss Haimhausen played a pivotal role in liaising with

the American troops. They provided crucial information about the

cultural and historical significance of the Schloss and its contents,

persuading the troops to spare it from harm. This interaction

highlighted the importance of cultural diplomacy during times of

conflict.

Post-war, Schloss Haimhausen emerged as a symbol of cultural resilience. The successful preservation of its collection was a significant achievement, given the widespread destruction of cultural heritage sites across Europe. The Schloss's role in safeguarding the Bavarian State Library's collection was not just a testament to the ingenuity and dedication of Dr. Hofmann and his team but also a reflection of the broader efforts to protect cultural heritage during wartime.

Dr. Hofmann's foresight in the early years of the war proved invaluable during this period. He had established a network of contacts within the local community and among various military personnel, which he leveraged to negotiate the Schloss's safety. His diplomatic skills were crucial in ensuring that the Schloss was not used as a military base or subjected to unnecessary destruction.

Moreover,

the staff at Schloss Haimhausen played a pivotal role in liaising with

the American troops. They provided crucial information about the

cultural and historical significance of the Schloss and its contents,

persuading the troops to spare it from harm. This interaction

highlighted the importance of cultural diplomacy during times of

conflict.

Moreover,

the staff at Schloss Haimhausen played a pivotal role in liaising with

the American troops. They provided crucial information about the

cultural and historical significance of the Schloss and its contents,

persuading the troops to spare it from harm. This interaction

highlighted the importance of cultural diplomacy during times of

conflict. Post-war, Schloss Haimhausen emerged as a symbol of cultural resilience. The successful preservation of its collection was a significant achievement, given the widespread destruction of cultural heritage sites across Europe. The Schloss's role in safeguarding the Bavarian State Library's collection was not just a testament to the ingenuity and dedication of Dr. Hofmann and his team but also a reflection of the broader efforts to protect cultural heritage during wartime.

As

the war intensified, Schloss Haimhausen's role in safeguarding the

Bavarian State Library's treasures became increasingly perilous. The

year 1943 marked a turning point; the relentless Allied bombing

campaigns were inching closer to the region. The Schloss's custodians,

led by Dr. Hofmann, were acutely aware of the impending danger. They

undertook meticulous measures to fortify the Schloss against potential

air raids and ground assaults. Sandbags were strategically placed around

the most vulnerable parts of the building, and fire-fighting equipment

was kept at the ready. In addition to physical preparations, Dr. Hofmann

initiated a series of discreet negotiations with local military

commanders.  His

objective was to secure a tacit understanding that Schloss Haimhausen

would be spared from deliberate targeting. These discussions were

fraught with risk, as they had to be conducted without arousing

suspicion from the Nazi authorities, who were increasingly paranoid

about any form of collaboration with the enemy.

His

objective was to secure a tacit understanding that Schloss Haimhausen

would be spared from deliberate targeting. These discussions were

fraught with risk, as they had to be conducted without arousing

suspicion from the Nazi authorities, who were increasingly paranoid

about any form of collaboration with the enemy.

The arrival of American forces in the region in 1945 brought a new set of challenges. Dr. Hofmann, aware of the potential for looting or inadvertent damage by occupying forces, sought to engage directly with the American military leadership. He provided detailed briefings on the cultural and historical significance of the Schloss and its contents. His efforts were instrumental in ensuring that the Schloss was treated with respect by the occupying forces.

Furthermore, the American officers stationed in the area, recognising the importance of the Schloss, appointed a small detachment to guard the premises. This move was unprecedented and highlighted the growing awareness among the Allied forces of the need to protect cultural heritage during conflict.

His

objective was to secure a tacit understanding that Schloss Haimhausen

would be spared from deliberate targeting. These discussions were

fraught with risk, as they had to be conducted without arousing

suspicion from the Nazi authorities, who were increasingly paranoid

about any form of collaboration with the enemy.

His

objective was to secure a tacit understanding that Schloss Haimhausen

would be spared from deliberate targeting. These discussions were

fraught with risk, as they had to be conducted without arousing

suspicion from the Nazi authorities, who were increasingly paranoid

about any form of collaboration with the enemy.The arrival of American forces in the region in 1945 brought a new set of challenges. Dr. Hofmann, aware of the potential for looting or inadvertent damage by occupying forces, sought to engage directly with the American military leadership. He provided detailed briefings on the cultural and historical significance of the Schloss and its contents. His efforts were instrumental in ensuring that the Schloss was treated with respect by the occupying forces.

Furthermore, the American officers stationed in the area, recognising the importance of the Schloss, appointed a small detachment to guard the premises. This move was unprecedented and highlighted the growing awareness among the Allied forces of the need to protect cultural heritage during conflict.

The immediate aftermath of the war presented a complex set of challenges for Schloss Haimhausen. The

post-war period saw Schloss Haimhausen transitioning back to a more

traditional role. However, the legacy of its wartime activities

continued to influence its operations. The strategies developed for

protecting and preserving the collection during the war years informed

future conservation efforts, setting a precedent for cultural

preservation in times of crisis. The

region, like much of Germany, was in a state of disarray. The Schloss,

having survived the war relatively unscathed, found itself in a unique

position. It was no longer just a repository for cultural treasures; it

had become a symbol of resilience and continuity amidst the ruins of

war.

.gif) Moving the books postwar back to the Staatsbibliothek on Ludwigstraße

showing the necessity for having relocated its collection with me at the site today. Between 1949

and 1975 the Schloss was used by the Bavarian Legal Aid School and

later the Munich Police Academy. Between 1976 and 1986 the International

Antiques Salon occupied all rooms with its period exhibits.

In the years following the war, Schloss Haimhausen underwent a period

of transformation. The Bavarian government, recognising the Schloss's

significance, initiated a series of restoration and preservation

projects. These efforts were not merely about repairing physical damage;

they were aimed at revitalising the cultural and historical essence of

the Schloss. One of the key figures in this era was Dr. Friedrich

Wilhelm, a historian and conservationist. Wilhelm played a pivotal role

in the restoration efforts. He advocated for a restoration approach that

respected the historical integrity of the Schloss, arguing against

modernisation that would erase the historical character of the building.

Under

Wilhelm's guidance, the restoration work at Schloss Haimhausen was

meticulous. Original materials and techniques were used wherever

possible, and artisans skilled in traditional methods were employed.

This approach ensured that the Schloss not only regained its former

glory but also retained its historical authenticity.

Moving the books postwar back to the Staatsbibliothek on Ludwigstraße

showing the necessity for having relocated its collection with me at the site today. Between 1949

and 1975 the Schloss was used by the Bavarian Legal Aid School and

later the Munich Police Academy. Between 1976 and 1986 the International

Antiques Salon occupied all rooms with its period exhibits.

In the years following the war, Schloss Haimhausen underwent a period

of transformation. The Bavarian government, recognising the Schloss's

significance, initiated a series of restoration and preservation

projects. These efforts were not merely about repairing physical damage;

they were aimed at revitalising the cultural and historical essence of

the Schloss. One of the key figures in this era was Dr. Friedrich

Wilhelm, a historian and conservationist. Wilhelm played a pivotal role

in the restoration efforts. He advocated for a restoration approach that

respected the historical integrity of the Schloss, arguing against

modernisation that would erase the historical character of the building.

Under

Wilhelm's guidance, the restoration work at Schloss Haimhausen was

meticulous. Original materials and techniques were used wherever

possible, and artisans skilled in traditional methods were employed.

This approach ensured that the Schloss not only regained its former

glory but also retained its historical authenticity.

In

the decades that followed, Schloss Haimhausen continued to evolve,

adapting to the changing needs and circumstances of the times. By the 1970s, the Schloss had become a venue for cultural events and exhibitions, hosting a range of activities from art shows to historical exhibitions. These events were not only popular with the local community but also attracted visitors from across Bavaria and beyond, helping to establish Schloss Haimhausen as a significant cultural landmark. The 1980s and 1990s saw further changes at Schloss Haimhausen. The Bavarian government, recognising the Schloss's potential as an educational centre, initiated a project to convert part of the building into a school. This decision was met with some controversy, as there were concerns about the impact of such a conversion on the historical integrity of the Schloss. However, careful planning and a commitment to preserving the Schloss's character ensured that the conversion was successful, blending the old with the new in a way that respected the building's heritage.

.gif) Moving the books postwar back to the Staatsbibliothek on Ludwigstraße

showing the necessity for having relocated its collection with me at the site today. Between 1949

and 1975 the Schloss was used by the Bavarian Legal Aid School and

later the Munich Police Academy. Between 1976 and 1986 the International

Antiques Salon occupied all rooms with its period exhibits.

In the years following the war, Schloss Haimhausen underwent a period

of transformation. The Bavarian government, recognising the Schloss's

significance, initiated a series of restoration and preservation

projects. These efforts were not merely about repairing physical damage;

they were aimed at revitalising the cultural and historical essence of

the Schloss. One of the key figures in this era was Dr. Friedrich

Wilhelm, a historian and conservationist. Wilhelm played a pivotal role

in the restoration efforts. He advocated for a restoration approach that

respected the historical integrity of the Schloss, arguing against

modernisation that would erase the historical character of the building.

Under

Wilhelm's guidance, the restoration work at Schloss Haimhausen was

meticulous. Original materials and techniques were used wherever

possible, and artisans skilled in traditional methods were employed.

This approach ensured that the Schloss not only regained its former

glory but also retained its historical authenticity.

Moving the books postwar back to the Staatsbibliothek on Ludwigstraße

showing the necessity for having relocated its collection with me at the site today. Between 1949

and 1975 the Schloss was used by the Bavarian Legal Aid School and

later the Munich Police Academy. Between 1976 and 1986 the International

Antiques Salon occupied all rooms with its period exhibits.

In the years following the war, Schloss Haimhausen underwent a period

of transformation. The Bavarian government, recognising the Schloss's

significance, initiated a series of restoration and preservation

projects. These efforts were not merely about repairing physical damage;

they were aimed at revitalising the cultural and historical essence of

the Schloss. One of the key figures in this era was Dr. Friedrich

Wilhelm, a historian and conservationist. Wilhelm played a pivotal role

in the restoration efforts. He advocated for a restoration approach that

respected the historical integrity of the Schloss, arguing against

modernisation that would erase the historical character of the building.

Under

Wilhelm's guidance, the restoration work at Schloss Haimhausen was

meticulous. Original materials and techniques were used wherever

possible, and artisans skilled in traditional methods were employed.

This approach ensured that the Schloss not only regained its former

glory but also retained its historical authenticity. %20(1).gif) |

| The schloss during the war and today |

.gif) The

role the schloss played in preserving our shared past and passing it on

to future generations free from war and violence makes Bavarian

International School's logo particularly resonant. In 1944 the

Bayerischen Staatsbibliothek was bombed along with most of Munich’s

centre. Fortunately, just before, it had distributed its collection of

books to 28 different sites around Oberbayern. One of those sites was

our Schloss chapel used today in the service of our students. I always

felt it rather touching to think that the logo was a representation of

this- that something vital and profound was preserved for future

generations even after this country’s darkest period when none knew what

would be left at null stunde when there was nothing left to believe in.

And there it is- our Schloss, like Pandora’s box in stone, from which a

single book is presented in hope and expectation to inspire success.

The

role the schloss played in preserving our shared past and passing it on

to future generations free from war and violence makes Bavarian

International School's logo particularly resonant. In 1944 the

Bayerischen Staatsbibliothek was bombed along with most of Munich’s

centre. Fortunately, just before, it had distributed its collection of

books to 28 different sites around Oberbayern. One of those sites was

our Schloss chapel used today in the service of our students. I always

felt it rather touching to think that the logo was a representation of

this- that something vital and profound was preserved for future

generations even after this country’s darkest period when none knew what

would be left at null stunde when there was nothing left to believe in.

And there it is- our Schloss, like Pandora’s box in stone, from which a

single book is presented in hope and expectation to inspire success.

What a lovely proud logo that was- it couldn’t have been designed for

any other school on earth. Sadly, it was decided to replace it, at

considerable expense, with the kind of thoughtless logo that any Grade 6

child could have designed in a single lesson shown. The outcry was great enough that the old logo returned,

albeit with the Mussoliniesque motto "Believe, Inspire, Succeed" attached to it only

for it to be replaced yet again in 2021 with the much-hated 'B' on the right which could

represent anything.

What a lovely proud logo that was- it couldn’t have been designed for

any other school on earth. Sadly, it was decided to replace it, at

considerable expense, with the kind of thoughtless logo that any Grade 6

child could have designed in a single lesson shown. The outcry was great enough that the old logo returned,