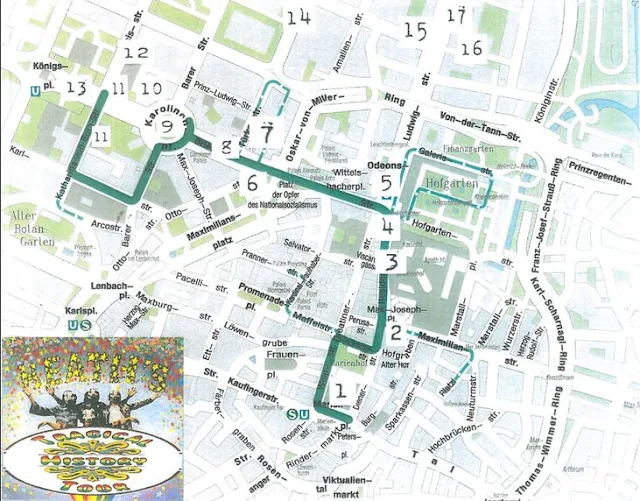

Script

for sites specified on Map

1. On 9 November 1938

it was the “Capital of the Movement” that gave the signal for the brutal and

centrally directed campaign of aggression against the Jews. What became known

as the “Reichspogromnacht” (“Night of Pogroms”) began with an inflammatory

speech by Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels in the Old Town Hall.

1. On 9 November 1938

it was the “Capital of the Movement” that gave the signal for the brutal and

centrally directed campaign of aggression against the Jews. What became known

as the “Reichspogromnacht” (“Night of Pogroms”) began with an inflammatory

speech by Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels in the Old Town Hall.

.

3. Nazi propaganda later reinterpreted the attempted putsch as a “March on the Feldherrnhalle”, analogous with Mussolini’s “March on Rome”. An “eternal vigil” was posted in front of the Feldherrnhalle round the clock, and passers- by were expected to give the Hitler salute. To avoid passing the Feldherrnhalle many Munich citizens took a detour through the Viscardigasse, which for this reason became popularly known as the “Drückebergergassl” (Dodgers’ Alley)

4.  The site of Hitler's failed 1923 putsch attempt where 16

Nazis and 4 police were killed, ten years later Hitler took power and made this

the site of his annual march to commemorate the event. A Nazi eagle was placed

on it with two 24 hour ϟϟ honour guards- one had to give the Hitler salute to

pass by. The plaque, often quoted in guides to the city, read:

The site of Hitler's failed 1923 putsch attempt where 16

Nazis and 4 police were killed, ten years later Hitler took power and made this

the site of his annual march to commemorate the event. A Nazi eagle was placed

on it with two 24 hour ϟϟ honour guards- one had to give the Hitler salute to

pass by. The plaque, often quoted in guides to the city, read:

The site of Hitler's failed 1923 putsch attempt where 16

Nazis and 4 police were killed, ten years later Hitler took power and made this

the site of his annual march to commemorate the event. A Nazi eagle was placed

on it with two 24 hour ϟϟ honour guards- one had to give the Hitler salute to

pass by. The plaque, often quoted in guides to the city, read:

The site of Hitler's failed 1923 putsch attempt where 16

Nazis and 4 police were killed, ten years later Hitler took power and made this

the site of his annual march to commemorate the event. A Nazi eagle was placed

on it with two 24 hour ϟϟ honour guards- one had to give the Hitler salute to

pass by. The plaque, often quoted in guides to the city, read:

The Feldherrnhalle is

bound for all times with the names of the men who gave their lives on 9

November 1923 for the movement and the rebirth of Germany.

Two ϟϟ men stood on

constant guard in front; pedestrians were required to give the Nazi salute as

they went by. One British visitor recalled how Germans’ arms "shot up as

though in reflex to an electric beam’ when they passed."

5. In front was a commemorative plaque to the four policemen

who died during the shootings which read: To the members of the Bavarian

Police, who gave their lives opposing the National Socialist coup on 9 November

1923. For unexplained reasons, this plaque has been removed and a blank space

remains; even the Nazis had a plaque honouring them.

New recruits to the SS were sworn in here during torch-lit,

midnight ceremonies.

The paving stone motif is still in the imperial colours. It

was here on the steps of the Feldherrnhalle, that Reinhold Elstner, a German

Wehrmacht veteran and chemist born in 1920 in the predominantly German

inhabited Sudetenland (now in the Czech Republic), poured petrol over himself

and committed suicide at about 20.00 on April 25, 1995, in protest against what

he called "the ongoing official slander and daemonisation of the German

people and German soldiers 50 years after the end of World War II".

6. An eternal flame burns in memory of victims of the Nazis

(the victims being left intentionally vague). When it was first erected, it was

shut off each night until enough of a protest had been made. By October 2012 it

was missing altogether.

7. In 1933 the Wittelsbach became the headquarters of the

Bavarian Political Police, which later became part of the Gestapo (Geheime

Staatspolizei or secret state police). This regional headquarters of terror

spread fear and dread among the population. Anyone resisting the regime in

Munich fell into the clutches of the Gestapo. Gestapo officials here were also

responsible for issuing orders to compile death lists and for dispatching the

deportation orders that led to the annihilation of Munich’s Jewish community. The original building

was destroyed in bombing in 1944; this plaque on its façade on the corner of

Brienner and Türkenstrasse marks the former site. Although the site is infamous

as a place of torture and imprisonment of the enemies of the regime, the plaque

seems more concerned about ignoring this inconvenient fact to advertise the

bombing by the British and Americans. Hitler’s

planned mausoleum was to be built behind.

8. House of German Physicians, inaugurated in 1935, played a key role in banning Jewish doctors. Its members included not only the ideologues of racially based medicine but also the advocates of medical experiments on humans, forced sterilisation and “euthanasia”.

9. Hitler referred to

this obelisk in the Karolinenplatz erected to the memory of 30,000 Bavarian

soldiers who were sent to fight for Napoleon and died in Russia in his final

speech before the court on March 27, 1924 during his putsch trial when he

declared: "It will be said one day, I can assure you, of the young men who

died in the uprising what the words on the Obelisk say: 'They too died for the

Fatherland!' All around the square are

buildings and houses of importance to the history of the Nazis.

10. Palais Barlow was bought by the Nazis in 1930 and converted

into the party headquarters, known as the “Brown House”. It housed the offices

of various party organisations and high- ranking Nazi personnel, including

Hitler’s deputy Rudolf Heß and the head of the party’s legal office, Hans

Frank. A documentation centre where visitors could learn about political

history is now located at the site of the former “Brown House” (destroyed

during the war) .

11. Temples of Honour- It was in 1935 that the remains of

the sixteen putschists were brought here on the anniversary. This had followed

the purge of the SA during the Night of the Long Knives the year before. The

bodies were exhumed from their graves and taken to the Feldherrnhalle where

they were interred in a sarcophagus bearing their name. It was one of the sites

most sacred to the Nazis.

In 1947 the upper parts of the structures were blown up. The

central portion was subsequently partially filled in but often filled with rain

water which created a natural memorial. When Germany was finally reunited plans

were made for a biergarten, restaurant or café on the site of the Ehrentempel

but these were derailed by the growth of rare biotope vegetation on the site.

As a result the foundation bases of the monuments remain; a small plaque added in 2007 explains their

function.

12 Site of the

Führerbau where meetings with high-ranking guests from foreign states were

held. Here the ground was prepared for important foreign policy moves – for

example, in talks between Hitler and the Italian dictator Benito Mussolini.

12 Site of the

Führerbau where meetings with high-ranking guests from foreign states were

held. Here the ground was prepared for important foreign policy moves – for

example, in talks between Hitler and the Italian dictator Benito Mussolini.

12 Site of the

Führerbau where meetings with high-ranking guests from foreign states were

held. Here the ground was prepared for important foreign policy moves – for

example, in talks between Hitler and the Italian dictator Benito Mussolini.

12 Site of the

Führerbau where meetings with high-ranking guests from foreign states were

held. Here the ground was prepared for important foreign policy moves – for

example, in talks between Hitler and the Italian dictator Benito Mussolini.

At the height of the Sudeten crisis in Czechoslovakia a

meeting was held in September 1938 attended by Hitler, Mussolini, French Prime

Minister Daladier and British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain which ended

here with the Munich Agreement, which was to have grave consequences: in a bid

to achieve “peace in our time” Chamberlain allowed a policy of appeasement which

represented a major foreign policy victory for Hitler.

13. Königsplatz was the centre of the Nazi-government. The

whole area was occupied by various NS-organisations. In 1933 Königsplatz was

the venue for one of the first major public demonstrations of power. During the

nationally organised book-burning on 10 May 1933, "un-Germanic" books

were burned here. In 1935 twenty thousand

granite paving slabs were laid on the square like Tiananmen Square after the

1989 massacre to better run over people with tanks, and had 18 street lamps and

two flag poles and it was equipped with a modern electrical system capable of

providing theatrical lighting for public events. With the two Temples of Honour

and two monumental party buildings, the square was turned into the central

parade ground for mass rallies in Munich. The granite was removed in 1988 and

grassed over. Every year since 1995 the

artist Wolfram P. Kastner has singed a patch of grass in front of the

Antikensammlung as a token of remembrance of the public book-burning accompanied

each year by public readings from the “burnt books”. The first reading took place in 1995 and is now a regular fixture

in the city’s culture of remembrance.

13. Königsplatz was the centre of the Nazi-government. The

whole area was occupied by various NS-organisations. In 1933 Königsplatz was

the venue for one of the first major public demonstrations of power. During the

nationally organised book-burning on 10 May 1933, "un-Germanic" books

were burned here. In 1935 twenty thousand

granite paving slabs were laid on the square like Tiananmen Square after the

1989 massacre to better run over people with tanks, and had 18 street lamps and

two flag poles and it was equipped with a modern electrical system capable of

providing theatrical lighting for public events. With the two Temples of Honour

and two monumental party buildings, the square was turned into the central

parade ground for mass rallies in Munich. The granite was removed in 1988 and

grassed over. Every year since 1995 the

artist Wolfram P. Kastner has singed a patch of grass in front of the

Antikensammlung as a token of remembrance of the public book-burning accompanied

each year by public readings from the “burnt books”. The first reading took place in 1995 and is now a regular fixture

in the city’s culture of remembrance.

14 The home of Georg

Elser, who attempted to assassinate Hitler by planting a bomb in Munich’s

Bürgerbräukeller on 8 November 1939 and was shot in Dachau concentration camp.

For a long time he went unacknowledged. Starting in the late 1960s several

attempts were made to have a street named after Elser. It was not until 1997

that a small square off Türkenstraße that Elser had passed every day on his way

to the Bürgerbräukeller was named Georg-Elser-Platz.

15. After the Great War Hitler received here some form of political

training; he realised for the first time that he could make an impact on those

around him. Here he heard lectures from prominent figures in Munich.

This was also the site of the apprehension of Hans and Sophie Scholl of the

White Rose (Weiße Rose), a non-violent resistance consisting of a number of

students from the University of Munich and their philosophy professor. The

group became known for an anonymous leaflet campaign, lasting from June 1942

until February 1943, that called for active opposition to Hitler's regime. They

were found guilty of treason and Roland Freisler, head judge of the court,

sentenced them to death. The three were beheaded. All three were noted for the

courage with which they faced their deaths, particularly Sophie, who remained

firm despite intense interrogation, and said to Freisler during the trial,

"You know as well as we do that the war is lost. Why are you so cowardly

that you won't admit it?" A memorial to them is in front of the entrance.

15. After the Great War Hitler received here some form of political

training; he realised for the first time that he could make an impact on those

around him. Here he heard lectures from prominent figures in Munich.

This was also the site of the apprehension of Hans and Sophie Scholl of the

White Rose (Weiße Rose), a non-violent resistance consisting of a number of

students from the University of Munich and their philosophy professor. The

group became known for an anonymous leaflet campaign, lasting from June 1942

until February 1943, that called for active opposition to Hitler's regime. They

were found guilty of treason and Roland Freisler, head judge of the court,

sentenced them to death. The three were beheaded. All three were noted for the

courage with which they faced their deaths, particularly Sophie, who remained

firm despite intense interrogation, and said to Freisler during the trial,

"You know as well as we do that the war is lost. Why are you so cowardly

that you won't admit it?" A memorial to them is in front of the entrance. 16. Constructed by

Oswald Eduard Bieber and inaugurated in 1939, this served as Hans Frank's

headquarters as Bavarian Minister of Justice and Reich Commissioner for the

Gleichschaltung of jurisdiction in the Federal States before being made

Governor-General of occupied Poland. To him the Haus des Deutschen Rechts was

an "NSDAP ideal set in stone."

16. Constructed by

Oswald Eduard Bieber and inaugurated in 1939, this served as Hans Frank's

headquarters as Bavarian Minister of Justice and Reich Commissioner for the

Gleichschaltung of jurisdiction in the Federal States before being made

Governor-General of occupied Poland. To him the Haus des Deutschen Rechts was

an "NSDAP ideal set in stone." 17. This gate, modelled on Constantine’s arch in Rome and

looking like a miniature version of Paris’s Arc de Triomphe, was commissioned

by King Ludwig I of Bavaria in 1840 and completed in 1852, in honour of

Bavarian troops who had triumphed against Napoleon. Crowned by a triumphant

Bavaria piloting a lion-drawn chariot, like the Brandenburg Gate it is supposed

to now represent a reminder to peace; severely damaged in WWII, the arch was

turned into a peace memorial whose inscription at the rear reads Dem Sieg

geweiht, vom Krieg zerstört, zum Frieden mahnend: "Dedicated to victory,

destroyed by war, reminding of peace".

17. This gate, modelled on Constantine’s arch in Rome and

looking like a miniature version of Paris’s Arc de Triomphe, was commissioned

by King Ludwig I of Bavaria in 1840 and completed in 1852, in honour of

Bavarian troops who had triumphed against Napoleon. Crowned by a triumphant

Bavaria piloting a lion-drawn chariot, like the Brandenburg Gate it is supposed

to now represent a reminder to peace; severely damaged in WWII, the arch was

turned into a peace memorial whose inscription at the rear reads Dem Sieg

geweiht, vom Krieg zerstört, zum Frieden mahnend: "Dedicated to victory,

destroyed by war, reminding of peace".1. Refugees arriving 1945 to rebuild, Pegida today, route of the 1923 putsch

On November 9, 1938 Joseph Goebbels gave his hate-filled speech here that launched the nationwide Kristallnacht pogroms. A plaque at the entrance condemns National Socialism and states that Munich in 1945 became home for more than 143,000 refugees "who contributed considerably to the reconstruction and life of our city."

Today it is the site of weekly demonstrations against the current influx of migrants and the perceived Islamification of the country.

Around the square are numerous memorials commemorating the human cost of war- one plaque within the town hall expresses the “sorrow and shame of Munich’ s population as well as their horror at the silence that prevailed at the time;” a reference to the deportation of one thousand men, women and children from Munich to Kaunas who, five days later, murdered by firing squad. On another floor is the 'Memorial Room' to those members of the city administration who had fallen victim to the Third Reich or died in the two world wars, thus putting all on a par with the victims of the Nazi regime without questioning the circumstances in which they died or of any consideration of political and moral responsibility.

2. Protests, the 1923 putsch and 1995 self immolation

The Feldherrnhalle on Munich’s Odeonsplatz, the nineteenth- century memorial to the Bavarian Army, took on new significance after the Nazis came to power. The site of Hitler's failed 1923 putsch attempt where 16 Nazis and 4 police were killed, ten years later Hitler took power and made this the site of his annual march to commemorate the event. A Nazi eagle was placed on it with two 24 hour SS honour guards- one had to give the Hitler salute to pass by. The plaque, often quoted in guides to the city, read:

The Feldherrnhalle is bound for all times with the names of the men who gave their lives on 9 November 1923 for the movement and the rebirth of Germany.Two ϟϟ men stood on constant guard in front; pedestrians were required to give the Nazi salute as they went by. One British visitor recalled how Germans’ arms "shot up as though in reflex to an electric beam’ when they passed."

To avoid having to do perform the salute, people would walk down a path behind the monument on Viscardigasse, an alley that people used to avoid having to salute the monuments, hence the nickname 'Shirker's Alley.' In 1998 bronze stones were placed to commemorate this 18 metres in length and 30 cm in width, designed by Bruno Wank. As with most memorials in Munich, there is no public notice explaining the significance of the bronze trail and the role of the Viscardigasse during the Nazi era.

f

f

"Dachau - Velden - Buchenwald

(Ich schäm)e mich, dass ich ein Deutscher bin - I am ashamed to be a German

Later

on the corner of the monument facing the Residence was written“Keine

Scham, nur Vergeltung! – Hakenkreuz – Schandkreuz" (No shame, only

resistance - Swastika = Cross of Shame) and again days later under it:

“Goethe, Diesel, Haydn, Rob. Koch. Ich bin stolz, eine Deutscher zu

sein!" (I am proud to be a German!)(Ich schäm)e mich, dass ich ein Deutscher bin - I am ashamed to be a German

Protests organised by anti-Islamic group PEGIDA at the historically-charged site

3. Forgetting: Gestapo HQ, Eternal Flame, Medical HQ, Israeli Consulate, Obelisk, Temples of Honour, Nazi Museum.\

Artists and intellectuals have critically observed how West Germany had dealt with its Nazi past and legacy where theatrical plays, exhibits, films, literature and journalism have sought to keep memories alive. Controversies have arisen in Munich over the stance of the Catholic church during the Third Reich and the role of the Wehrmacht in Nazi wars of annihilation. In the immediate postwar years, those who had been persecuted were primarily the ones to keep alive the memory of Nazi crimes. They demanded that perpetrators be brought to justice and fought for victims to be compensated and honoured. Starting in the 1980s, with the passing of generations and changes in social values, this movement found broader resonance and support. More and more Munich residents actively spoke out against anti-Semitism and right-wing radicalism. the 'Chain of Lights' demonstration, staged for the first time December 6, 1992, became the largest statement against extreme right-wing ideas and violence ever conducted in Germany. Nearly 400,000 people took to the streets in response to the fire-bombing in the northern city of Mölln that killed two Turkish girls and their grandmother. Five years later nearly 15,000 people turned out to resist 4,000 neo-Nazis protesting the exhibit 'War of Annihilation: Crimes of the Wehrmacht 1941-1944' held in the rathaus.

The Square for the Victims of National Socialism (which could refer almost to anyone) is situated diagonally opposite from the former Wittelsbach Palace, Gestapo headquarters and gaol in Munich since 1933. The memorial information slab describes the site as "a place of destruction, intimidation and terror against political dissidents, against racially and religiously discredited minorities and against people who have been persecuted because of their sexual orientation or disability."

When it was first erected, it was shut off each night until enough of a protest had been made.

In 1944 the building was destroyed by Allied bombing. On the right is a short introduction related to the establishment of the Gestapo. Today the site is occupied by the Bayerischen Landesbank. The original building was destroyed in bombing in 1944; this plaque on its façade on the corner of Brienner and Türkenstrasse marks the former site. Although the site is infamous as a place of torture and imprisonment of the enemies of the regime, the plaque seems more concerned about ignoring this inconvenient fact to advertise the bombing by the British and Americans.

The House of German Physicians, inaugurated in 1935, played a key role in banning Jewish doctors. Its members included not only the ideologues of racially based medicine but also the advocates of medical experiments on humans, forced sterilisation and “euthanasia”. The medical snakes and faint remains of the lettering on the façade preserve its original role. Ironically it is sited next to the Israeli consulate across the street from the former Gestapo HQ on what was Adolf-Hitler-Straße.

If the Feldherrnhalle honours those who fought against Napoleon, this obelisk in the Karolinenplatz commemorates the 30,000 Bavarian soldiers who were sent to fight for

Napoleon and died in Russia. In his final speech before the court on

March 27, 1924 during his putsch trial, Hitler declared: "It will be

said one day, I can assure you, of the young men who died in the

uprising what the words on the Obelisk say: 'They too died for the

Fatherland!' That is the visual proof of the success of November eight,

that in its wake youth rises like a raging flood and is united. That is

the great success of the eighth of November: it has not led to

depressed spirits but has brought the people to the highest pitch of

enthusiasm. I believe that the hour will come when the masses who today

bear our crusading flags on the streets will join with those on

November eight shot at them." In fact, when Hitler often maintained in

party circles that the victims of June 30 had died “for the liberation

of the Vaterland,” he was alluding to the same inscription and had

actually granted substantial pensions to the survivors of those slain

on June 30, 1934.

Hitler's Brown House has been replaced by the Nazi Documentation Centre whilst the 'temples of honour' housing the remains of the 16 Nazis killed during the 1923 Hitler putsch, although blown up by the Americans in 1947, still have their bases upon which vegetation has been allowed to grow and partially obscure. 4. Konigsplatz: Brecht and book burning and memorial.

Artist Wolfram Kastner initiated an art project here to commemorate the Nazi-initiated book burning by singeing a piece of turf exactly where, on May 10, 1933 many books by ostracised authors had been burned. The Nazis had organised such burnings of around 130 authors on pyres in around 20 German university towns. In this way Kastner was protesting the literal cover-up by the Munich authorities who grassed-over the area- No grass is allowed to grow over the story," said Kastner. Volunteers then read extracts from these so-called "enemies of the Reich" which included Bertolt Brecht, Heinrich and Klaus Mann, Alfred Doblin, Erich Maria Remarque and Kurt Tucholsky. Nationwide is remembered with numerous commemorative events and readings of the book burnings.

5. Art as Protest: Degenerate Art, and contrasting memorials, Landtag (use of glass/transparency)

The tomb of the Unknown Soldier then and today. Built in 1924 to commemorate the 2 million dead of the Great War, the 'Dead Soldier' is now dedicated to the dead of both world wars. It was also used as a backdrop for nationalist and militaristic propaganda during the Nazi era. Damaged during the Second World War, the war memorial was restored on the orders of the American military government, albeit without the names of the 13,000 dead. In the 1950s an inscription was added commemorating the fallen soldiers and civilian victims of the years 1939 to 1945 reflecting the desire of the population to continue commemorating the war dead even after 1945, although its portrayal of both the city and its population exclusively as victims has been criticised as representing a very one-dimensional view. To this day military ceremonies in honour of the dead are still held regularly at the war memorial.

The Bavarian State Chancellery after the war and reconstructed with glass wings

In front is Leo Kornbrust’s memorial to the resistance to the Nazis, unveiled in 1996 and engraved on one side with a line of block letters reading "Zum erinnern zum gedenken" ("To Recall and to Commemorate") under which is a reproduction of a handwritten letter by Generalfeldmarschall Erwin von Witzleben who was arrested the day after the attempted July plot and executed. The propaganda exhibition of "Degenerate Art" was organised by the Nazis and opened in the Hofgarten arcades in 1937. They displayed the maligned art styles of Expressionism, Dadaism, Surrealism and New Objectivity through a chaotic effect whereby the works were hung in the showrooms in a deliberately disadvantageous perspective and provided with abusive slogans on the walls. The exhibition, according to official figures, saw 2,009,899 visitors and was at that time one of the most visited exhibitions of modern art. William Shirer would claim that such numbers became so great that the Nazis, "incensed and embarrassed, soon closed it."

The 1938 law that allowed the Nazis to seize thousands of other Modernist artworks deemed “degenerate” because Hitler viewed them as un-German or Jewish in nature remains on the books to this day.

Hitler across the street at the House of German Art, the first realised Nazi building, where he opened the annual exhibitions of what he considered German art. He would make a reappearance in Maurizio Cattelan's Him in 2003. Highly controversial, its point was intended to make people reflect on the nature of evil.

6. University: Sophie Scholl, Janitor, Georg Elser

It was at the University where Hitler had been assigned by the army to the first of the anti-Bolshevik ‘instruction courses’ in 1919 where he received some form of directed political ‘education’. This, as he acknowledged, was important to him; as was the fact that he realized for the first time that he could make an impact on those around him.

This was also the site of the apprehension of Hans and Sophie Scholl of the White Rose (Weiße Rose), a non-violent resistance group in Nazi Germany, consisting of a number of students from the University of Munich and their philosophy professor. The group became known for an anonymous leaflet campaign, lasting from June 1942 until February 1943, that called for active opposition to Hitler's regime. The core of the group comprised of students from this university, most in their early twenties, with support from their professor of philosophy and musicology, Kurt Huber.

At her trial Sophie Scholl declared to the notorious judge "You know as well as we do that the war is lost. Why are you so cowardly that you won't admit it?" When her brother Hans put his head on the block, he shouted: “Long live freedom!”

Despite their iconic status today, the subject of numerous memorials, books and a recent film, at the time they were seen as traitors. The janitor who had apprehended them had been honoured during a demonstration of 3,000 students eager to express their loyalty to the regime after the executions had taken place.

Whilst Stauffenberg and other members of the military resistance were honoured as patriots for their July 20, 1944 attempt on Hitler's life, others, such as Municher Georg Elser who had been minutes away from blowing up Hitler in November 1939 have been ignored given that their political sympathies lay on the left.