During

my 2021 Bavarian International School class trip and as it appeared in a

photograph taken in 1955 by Estella Burket, a teacher at Deseronto

Public School, Deseronto, Ontario, in the Dominion of Canada. After

the war, four Soviet memorial sites were

created by the Red Army in the urban area of Berlin.

These sites are not only monuments to the victory over Germany, but also serve as Soviet war grave sites in Germany. The

central monument is this, the complex in Treptow Park. The memorial in

the Schönholzer Heide, the memorial in the Tiergarten and the

memorial at Bucher castle grounds were also built for this purpose.

A contest had been organised by the Soviet Command for the design of the

memorial in Berlin-Treptow, to which 33 drafts were submitted. From

June 1946, the proposal of a Soviet creator collective, designed by the

architect Jakov S. Belopolski, the sculptor Yevgeny Wuchetich, the

painter Alexander A. Gorpenko, and the engineer Sarra S. Walerius, was

implemented. The sculptures and reliefs were manufactured in 1948

by the Lauchhammer art foundry. The memorial was built on the site

of a large play and sports meadow in the area of the "New Lake", which

was created during the Berlin trade exhibition of 1896 and completed in May 1949.

During

my 2021 Bavarian International School class trip and as it appeared in a

photograph taken in 1955 by Estella Burket, a teacher at Deseronto

Public School, Deseronto, Ontario, in the Dominion of Canada. After

the war, four Soviet memorial sites were

created by the Red Army in the urban area of Berlin.

These sites are not only monuments to the victory over Germany, but also serve as Soviet war grave sites in Germany. The

central monument is this, the complex in Treptow Park. The memorial in

the Schönholzer Heide, the memorial in the Tiergarten and the

memorial at Bucher castle grounds were also built for this purpose.

A contest had been organised by the Soviet Command for the design of the

memorial in Berlin-Treptow, to which 33 drafts were submitted. From

June 1946, the proposal of a Soviet creator collective, designed by the

architect Jakov S. Belopolski, the sculptor Yevgeny Wuchetich, the

painter Alexander A. Gorpenko, and the engineer Sarra S. Walerius, was

implemented. The sculptures and reliefs were manufactured in 1948

by the Lauchhammer art foundry. The memorial was built on the site

of a large play and sports meadow in the area of the "New Lake", which

was created during the Berlin trade exhibition of 1896 and completed in May 1949.  The

construction of the monument was marked by the beginning of the Cold

War. Although there was a lack of living space in post-war Germany and

the construction sector had almost come to a standstill due to the lack

of planning, labour and material shortages, Soviet propaganda demands

took priority over housing construction. This site was to express two

ideas: on the one hand, an appreciation of Soviet occupation power so

that the scale of the area should be "a witness of the greatness and the

insuperable power of Soviet power." East German politicians like Otto

Grotewohl, on the other hand, saw in the memorial on May 8, 1949, the

fourth anniversary of the end of the war, a sign of gratitude to the

Soviet army as a liberator. In

the following decades, the Treptower site was the scene of mass events

and state rituals of the DDR, which sometimes completely superimposed

the original intention of being the victory mark and cemetery of the

Second World War. In 1985, on the 40th anniversary of the end of the

war, the representatives of the youth movement of the DDR organised a

torchlight procession at the Treptower Memorial. There they took the

"oath of the youth of the DDR" on their behalf.

The

construction of the monument was marked by the beginning of the Cold

War. Although there was a lack of living space in post-war Germany and

the construction sector had almost come to a standstill due to the lack

of planning, labour and material shortages, Soviet propaganda demands

took priority over housing construction. This site was to express two

ideas: on the one hand, an appreciation of Soviet occupation power so

that the scale of the area should be "a witness of the greatness and the

insuperable power of Soviet power." East German politicians like Otto

Grotewohl, on the other hand, saw in the memorial on May 8, 1949, the

fourth anniversary of the end of the war, a sign of gratitude to the

Soviet army as a liberator. In

the following decades, the Treptower site was the scene of mass events

and state rituals of the DDR, which sometimes completely superimposed

the original intention of being the victory mark and cemetery of the

Second World War. In 1985, on the 40th anniversary of the end of the

war, the representatives of the youth movement of the DDR organised a

torchlight procession at the Treptower Memorial. There they took the

"oath of the youth of the DDR" on their behalf.  At

the site with my students holding one of my wartime Soviet flags and

the same spot on May 8, 1956 with an honorary formation of the National

People's Army in front of the Soviet memorial. The memorial’s

significance goes beyond its architectural grandeur or the scale of loss

it commemorates. It has long been a site of political symbolism. In the

immediate post-war years, as the Soviet Union consolidated its control

over East Germany, the memorial became a focal point for the DDR's

official historical narrative. Through state-sponsored ceremonies and

school visits, it was promoted as a site of pilgrimage, representing

both the brotherhood of Soviet and East German socialism and the eternal

debt owed by East Germany to the Soviet Union. This close association

with Soviet power made the memorial not just a symbol of victory over

fascism but also a potent marker of Soviet dominance in Eastern Europe.

Consequently, for many East Germans, it came to embody the

contradictions of their national identity, simultaneously representing

liberation and subjugation. Scholarly interpretations of the memorial

reflect this duality. Sebestyen argues that the Soviet-designed war

memorials across Eastern Europe, including Treptower Park, were intended

as much to intimidate as to commemorate. The massive scale,

militaristic iconography, and positioning of such memorials were,

according to Sebestyen, reminders of Soviet control rather than simply

tributes to wartime sacrifices. This perspective sees the memorial as a

tool of Soviet soft power, particularly in the years following 1945 when

the Soviet Union sought to solidify its ideological and military

presence in the region. The deliberate evocation of Soviet heroism,

portrayed in such grand terms, was integral to the GDR’s legitimisation

strategy, binding the country closer to Moscow and reinforcing the

Soviet Union’s role as a paternal protector of the socialist bloc. Yet,

the post-Cold War era has complicated this narrative. Following the

reunification of Germany in 1990 and the dissolution of the Soviet

Union, the memorial has faced a re-examination within the context of

German historical memory. Initially, there were calls from some segments

of German society to dismantle Soviet-era monuments, seen as relics of

foreign occupation and dictatorship. However, Treptower Park's

significance as a grave for thousands of soldiers has largely preserved

it from such fate, unlike other Soviet statues removed from public

spaces across Eastern Europe. In Berlin, where the history of the Second

World War and its aftermath looms large, the memorial has retained a

certain sanctity, protected in part by the treaties between Germany and

Russia, which guarantee its preservation. As such, it remains a space

where annual commemorations are held, not only by Russian and German

officials but also by anti-fascist groups, who view the site as a symbol

of the defeat of Nazism. However, the memorial's legacy is not without

its tensions. Whilst it continues to serve as a site of remembrance, it

is also a point of contention, particularly among those who view it as a

vestige of Soviet oppression. The Red Army’s actions during the

occupation of Germany, including widespread evidenced reports of

looting, rape, and destruction, complicate the narrative of liberation

that the memorial seeks to promote. Naimark highlights the Soviet

occupation's dark legacy in Berlin, noting that whilst the Red Army’s

role in ending Nazi tyranny can't be discounted, its occupation policies

left deep scars on the German populace, particularly in the immediate

aftermath of the war. For those who suffered under Soviet rule, the

Treptower Memorial serves as a painful reminder not of liberation but of

subjugation and violence. As such, the site remains contested, with

some viewing it as an essential symbol of anti-fascism and others as a

monument to Soviet tyranny. The Treptower Soviet Memorial thus exists

within a web of competing historical interpretations, serving as both a

commemoration of wartime sacrifice and a flashpoint for the unresolved

historical traumas of the 20th century. Its continuing significance

today is a testament to the complexities of post-war memory in Germany

and the broader question of how societies reckon with the legacies of

occupation, war, and dictatorship. The careful preservation of the site

reflects a broader consensus within Germany to acknowledge the

contributions of the Soviet Union in defeating Nazi Germany while

simultaneously confronting the darker aspects of Soviet rule.The

entrance, 200 metres long and an hundred metres wide leads to six

bronze-cast wreaths measuring around ten metres in diameter. During

the fall of the Wall on December 28, 1989, strangers smeared the stone

sarcophagi and the base of the crypt with anti-Soviet slogans. The

SED-PDS suspected that the perpetrator or perpetrators came from the

right-wing extremist scene and organised a mass demonstration on January

3, 1990, in which 250,000 citizens of the DDR took part. Party chairman

Gregor Gysi took this opportunity to call for “protection of the

constitution” for the DDR. He was referring to the discussion of whether

the Office for National Security, the successor organisation to the

Stasi, should be reorganised or wound down. Historian Stefan Wolle

therefore considers it possible that behind the graffiti were Stasi

employees who feared for their posts. The Soviet war memorials were an

important negotiating point on the Russian side for the two-plus-four

treaties for German reunification.

At

the site with my students holding one of my wartime Soviet flags and

the same spot on May 8, 1956 with an honorary formation of the National

People's Army in front of the Soviet memorial. The memorial’s

significance goes beyond its architectural grandeur or the scale of loss

it commemorates. It has long been a site of political symbolism. In the

immediate post-war years, as the Soviet Union consolidated its control

over East Germany, the memorial became a focal point for the DDR's

official historical narrative. Through state-sponsored ceremonies and

school visits, it was promoted as a site of pilgrimage, representing

both the brotherhood of Soviet and East German socialism and the eternal

debt owed by East Germany to the Soviet Union. This close association

with Soviet power made the memorial not just a symbol of victory over

fascism but also a potent marker of Soviet dominance in Eastern Europe.

Consequently, for many East Germans, it came to embody the

contradictions of their national identity, simultaneously representing

liberation and subjugation. Scholarly interpretations of the memorial

reflect this duality. Sebestyen argues that the Soviet-designed war

memorials across Eastern Europe, including Treptower Park, were intended

as much to intimidate as to commemorate. The massive scale,

militaristic iconography, and positioning of such memorials were,

according to Sebestyen, reminders of Soviet control rather than simply

tributes to wartime sacrifices. This perspective sees the memorial as a

tool of Soviet soft power, particularly in the years following 1945 when

the Soviet Union sought to solidify its ideological and military

presence in the region. The deliberate evocation of Soviet heroism,

portrayed in such grand terms, was integral to the GDR’s legitimisation

strategy, binding the country closer to Moscow and reinforcing the

Soviet Union’s role as a paternal protector of the socialist bloc. Yet,

the post-Cold War era has complicated this narrative. Following the

reunification of Germany in 1990 and the dissolution of the Soviet

Union, the memorial has faced a re-examination within the context of

German historical memory. Initially, there were calls from some segments

of German society to dismantle Soviet-era monuments, seen as relics of

foreign occupation and dictatorship. However, Treptower Park's

significance as a grave for thousands of soldiers has largely preserved

it from such fate, unlike other Soviet statues removed from public

spaces across Eastern Europe. In Berlin, where the history of the Second

World War and its aftermath looms large, the memorial has retained a

certain sanctity, protected in part by the treaties between Germany and

Russia, which guarantee its preservation. As such, it remains a space

where annual commemorations are held, not only by Russian and German

officials but also by anti-fascist groups, who view the site as a symbol

of the defeat of Nazism. However, the memorial's legacy is not without

its tensions. Whilst it continues to serve as a site of remembrance, it

is also a point of contention, particularly among those who view it as a

vestige of Soviet oppression. The Red Army’s actions during the

occupation of Germany, including widespread evidenced reports of

looting, rape, and destruction, complicate the narrative of liberation

that the memorial seeks to promote. Naimark highlights the Soviet

occupation's dark legacy in Berlin, noting that whilst the Red Army’s

role in ending Nazi tyranny can't be discounted, its occupation policies

left deep scars on the German populace, particularly in the immediate

aftermath of the war. For those who suffered under Soviet rule, the

Treptower Memorial serves as a painful reminder not of liberation but of

subjugation and violence. As such, the site remains contested, with

some viewing it as an essential symbol of anti-fascism and others as a

monument to Soviet tyranny. The Treptower Soviet Memorial thus exists

within a web of competing historical interpretations, serving as both a

commemoration of wartime sacrifice and a flashpoint for the unresolved

historical traumas of the 20th century. Its continuing significance

today is a testament to the complexities of post-war memory in Germany

and the broader question of how societies reckon with the legacies of

occupation, war, and dictatorship. The careful preservation of the site

reflects a broader consensus within Germany to acknowledge the

contributions of the Soviet Union in defeating Nazi Germany while

simultaneously confronting the darker aspects of Soviet rule.The

entrance, 200 metres long and an hundred metres wide leads to six

bronze-cast wreaths measuring around ten metres in diameter. During

the fall of the Wall on December 28, 1989, strangers smeared the stone

sarcophagi and the base of the crypt with anti-Soviet slogans. The

SED-PDS suspected that the perpetrator or perpetrators came from the

right-wing extremist scene and organised a mass demonstration on January

3, 1990, in which 250,000 citizens of the DDR took part. Party chairman

Gregor Gysi took this opportunity to call for “protection of the

constitution” for the DDR. He was referring to the discussion of whether

the Office for National Security, the successor organisation to the

Stasi, should be reorganised or wound down. Historian Stefan Wolle

therefore considers it possible that behind the graffiti were Stasi

employees who feared for their posts. The Soviet war memorials were an

important negotiating point on the Russian side for the two-plus-four

treaties for German reunification.  The

Federal Republic therefore undertook in 1992 in the agreement of

December 16, 1992 between the Government of the Federal Republic of

Germany and the Government of the Russian Federation on War Graves Care

to permanently guarantee their existence, to maintain and repair them.

Any changes to the monuments require the approval of the Russian

Federation.On August 31, 1994, the military ceremony for the withdrawal

of Russian troops from Germany was held at the Soviet Memorial in

Treptower Park. After a ceremony in the Schauspielhaus on

Gendarmenmarkt, 1,000 Russian soldiers from the 6th Guards Mot.-Rifle

Brigade and six hundred German soldiers from the Guard Battalion at the

Federal Ministry of Defence came together to commemorate the dead. They

formed the framework for the wreath-laying ceremony, accompanied by

short speeches, by Chancellor Helmut Kohl and President Boris Jelzin.

Since 1995, a memorial rally has been held at the memorial every year on

May 9th with the laying of flowers and wreaths, which is organised by

the “Bund der Antifaschisten Treptow e. V. "is organised. The motto of

the event is “ Liberation Day ” and corresponds to Victory Day, the

Russian holiday. On the night of May 8-9 1945 in Berlin-Karlshorst the

unconditional surrender of the Wehrmacht by three leading German

military men, that of the last Reich President Karl Dönitz in the

special area Mürwik were authorised to do so, and signed by four Allied

representatives. On May 9, 2015, around 10,000 people visited the

memorial to commemorate the 70th anniversary of the end of the war -

among them were members of the Night Wolves, a Russian motorcycle and

rocker club. The bikers' trip to Berlin caused a sensation when some

members were initially refused entry to Germany. On September 2, 2015,

the inscriptions on a memorial plaque were destroyed by arson. On May 4,

2019, there was another incident in which the statue "Mother Homeland"

was doused with a dark liquid.

The

Federal Republic therefore undertook in 1992 in the agreement of

December 16, 1992 between the Government of the Federal Republic of

Germany and the Government of the Russian Federation on War Graves Care

to permanently guarantee their existence, to maintain and repair them.

Any changes to the monuments require the approval of the Russian

Federation.On August 31, 1994, the military ceremony for the withdrawal

of Russian troops from Germany was held at the Soviet Memorial in

Treptower Park. After a ceremony in the Schauspielhaus on

Gendarmenmarkt, 1,000 Russian soldiers from the 6th Guards Mot.-Rifle

Brigade and six hundred German soldiers from the Guard Battalion at the

Federal Ministry of Defence came together to commemorate the dead. They

formed the framework for the wreath-laying ceremony, accompanied by

short speeches, by Chancellor Helmut Kohl and President Boris Jelzin.

Since 1995, a memorial rally has been held at the memorial every year on

May 9th with the laying of flowers and wreaths, which is organised by

the “Bund der Antifaschisten Treptow e. V. "is organised. The motto of

the event is “ Liberation Day ” and corresponds to Victory Day, the

Russian holiday. On the night of May 8-9 1945 in Berlin-Karlshorst the

unconditional surrender of the Wehrmacht by three leading German

military men, that of the last Reich President Karl Dönitz in the

special area Mürwik were authorised to do so, and signed by four Allied

representatives. On May 9, 2015, around 10,000 people visited the

memorial to commemorate the 70th anniversary of the end of the war -

among them were members of the Night Wolves, a Russian motorcycle and

rocker club. The bikers' trip to Berlin caused a sensation when some

members were initially refused entry to Germany. On September 2, 2015,

the inscriptions on a memorial plaque were destroyed by arson. On May 4,

2019, there was another incident in which the statue "Mother Homeland"

was doused with a dark liquid.In the following decades, the Treptow site was at times completely superimposed on mass events and state rituals of the DDR. In 1985, on the occasion of the 40th anniversary of the end of the war, the representatives of the DDR's youth movement organised a torchlight procession at the Treptow Memorial.

There, they represented

the "oath of youth of the DDR". In the time of the invasion on 28

December 1989 strangers smeared the stone carcass and the base of the

crypt with anti-Soviet slogans. The SED-PDS suspected that the

perpetrators would come from the right-wing extremist scene and

organised a mass demonstration on January 3, 1990, involving 250,000

citizens of the DDR. On this occasion, Gregor Gysi, party chairman,

demanded "constitutional protection" for the site; historian Stefan

Wolle therefore considers it possible that Stasi employees were behind

the vandalism, fearing their positions upon re-unification.

There, they represented

the "oath of youth of the DDR". In the time of the invasion on 28

December 1989 strangers smeared the stone carcass and the base of the

crypt with anti-Soviet slogans. The SED-PDS suspected that the

perpetrators would come from the right-wing extremist scene and

organised a mass demonstration on January 3, 1990, involving 250,000

citizens of the DDR. On this occasion, Gregor Gysi, party chairman,

demanded "constitutional protection" for the site; historian Stefan

Wolle therefore considers it possible that Stasi employees were behind

the vandalism, fearing their positions upon re-unification.  I'm standing beside one of sixteen

white sarcophagi of limestone that stand along the outer boundary of

the field leading to the statue, this one displaying Lenin; all display war scenes

and historical moments through reliefs from the history of the Great Patriotic War

of the Soviet Peoples on the two long sides. On each of these is a quote from Stalin on the narrow side facing the central field; in Russian on

the left (northern) and in German on the right (southern). This one shows Lenin on a red banner

that flies behind the Soviet Red Army with a quote on the side embossed in

gold by Stalin. These sarcophagi are marked on the two longitudinal

sides with reliefs from the history of the Great Patriotic War of the

Soviet Peoples, bearing quotations from Joseph Stalin in Russian on the

left and in German on the right. The individual sarcophagi have specific

themes: the attack by the Germans, the destruction and suffering in the

Soviet Union, the sacrifice and abandonment of the Soviet people and

support of the army, the suffering of the army, victory, and heroic

death. Oaulk Stangle (225) writes

I'm standing beside one of sixteen

white sarcophagi of limestone that stand along the outer boundary of

the field leading to the statue, this one displaying Lenin; all display war scenes

and historical moments through reliefs from the history of the Great Patriotic War

of the Soviet Peoples on the two long sides. On each of these is a quote from Stalin on the narrow side facing the central field; in Russian on

the left (northern) and in German on the right (southern). This one shows Lenin on a red banner

that flies behind the Soviet Red Army with a quote on the side embossed in

gold by Stalin. These sarcophagi are marked on the two longitudinal

sides with reliefs from the history of the Great Patriotic War of the

Soviet Peoples, bearing quotations from Joseph Stalin in Russian on the

left and in German on the right. The individual sarcophagi have specific

themes: the attack by the Germans, the destruction and suffering in the

Soviet Union, the sacrifice and abandonment of the Soviet people and

support of the army, the suffering of the army, victory, and heroic

death. Oaulk Stangle (225) writes More problematic is the portrayal of Soviet innocence, which lacks validity due to the Ribbentrop-Molotov Pact's program for the future division of Europe between Germany and the Soviet Union, subsequent Red Army participation in the invasion of Poland in 1939, and the Soviet invasion of Finland in 1939-1940. Claims that the German invasion disrupted the Soviet Union's peaceful development ignored the forced collectivisation of agriculture and the Great Purge in which 19 million Soviet were arrested, a majority of whom either were executed or died in labour camps. Stalin, responsible for these atrocities and the disastrous lack of preparedness for the German invasion, was omitted from the narrative.Geographical Review , Apr., 2003, Vol. 93, No. 2

The figure shows a

soldier who carries a sword in his right hand and a protective child on

his left arm; a swastika is bursting under his boots. This memorial to the liberator as

part of geographic memorial triptych with his

mother on Mamayev Hill in Volgograd (1967) and the worker behind the

front in Magnitogorsk (1979) a showing the forged sword in

Magnitogorsk, the raised sword in Volgograd and the lowered sword in

Berlin. Here it serves as a mausoleum on which a ten to

twelve metre high bronze statue is placed depicting a bareheaded,

heroic, Soviet soldier wielding a sword and standing on a smashed

swastika, into which the sword is deeply cut. On his left arm he is

carrying a child while staring out over the plaza. This sculpture, "Der

Erreer" by Jewgeni Wuchetich, stands on a double conical base 12 metres

high and weighing 70 tonnes. The statue rises above a walk-in

pavilion built on a hill. In the dome of the pavilion is a mosaic with a

circulating Russian inscription and a German translation. This mosaic

was one of the first important orders in the post-war period for the

August Wagner company which

combined workshops for mosaic and glass painting in Berlin-Neukölln .

The hill itself is modelled after a "Kurgan" (mediæval, Slavic tombs on

the Don plain), often found in Soviet memorials such as those at

Volgograd, Smolensk, Minsk, Kiev, Odessa and Donetsk. On top marks the

outstanding endpoint of the 10-hectare complex. The sculptor himself

emphasised in several interviews that the representation of the soldier

with a child saved had a purely symbolic meaning and not a precise

incident. However, in the DDR the narrative of sergeant Nikolay

Ivanovich Massov, who had brought a little girl near the Potsdamer

bridge to safety on April 30, 1945 during the storming of the

Reichskanzlei, was widely circulated. In his honour, a memorial plaque

was erected on this bridge over the Landwehrkanal and for a long time he

was regarded as the model of the Treptow soldier. The model for the

bronze figure was the Soviet soldier Ivan Odartschenko. Another version

claims that the monument is modelled on the heroic deed of the Soviet

soldier and former worker of the Minsker Radiowerkes T. A. Lukyanovich,

who paid for the salvation of a little girl in Berlin with his life. The

source for this version is the book Berlin 896 km by Soviet journalist and writer Boris Polewoi.

The figure shows a

soldier who carries a sword in his right hand and a protective child on

his left arm; a swastika is bursting under his boots. This memorial to the liberator as

part of geographic memorial triptych with his

mother on Mamayev Hill in Volgograd (1967) and the worker behind the

front in Magnitogorsk (1979) a showing the forged sword in

Magnitogorsk, the raised sword in Volgograd and the lowered sword in

Berlin. Here it serves as a mausoleum on which a ten to

twelve metre high bronze statue is placed depicting a bareheaded,

heroic, Soviet soldier wielding a sword and standing on a smashed

swastika, into which the sword is deeply cut. On his left arm he is

carrying a child while staring out over the plaza. This sculpture, "Der

Erreer" by Jewgeni Wuchetich, stands on a double conical base 12 metres

high and weighing 70 tonnes. The statue rises above a walk-in

pavilion built on a hill. In the dome of the pavilion is a mosaic with a

circulating Russian inscription and a German translation. This mosaic

was one of the first important orders in the post-war period for the

August Wagner company which

combined workshops for mosaic and glass painting in Berlin-Neukölln .

The hill itself is modelled after a "Kurgan" (mediæval, Slavic tombs on

the Don plain), often found in Soviet memorials such as those at

Volgograd, Smolensk, Minsk, Kiev, Odessa and Donetsk. On top marks the

outstanding endpoint of the 10-hectare complex. The sculptor himself

emphasised in several interviews that the representation of the soldier

with a child saved had a purely symbolic meaning and not a precise

incident. However, in the DDR the narrative of sergeant Nikolay

Ivanovich Massov, who had brought a little girl near the Potsdamer

bridge to safety on April 30, 1945 during the storming of the

Reichskanzlei, was widely circulated. In his honour, a memorial plaque

was erected on this bridge over the Landwehrkanal and for a long time he

was regarded as the model of the Treptow soldier. The model for the

bronze figure was the Soviet soldier Ivan Odartschenko. Another version

claims that the monument is modelled on the heroic deed of the Soviet

soldier and former worker of the Minsker Radiowerkes T. A. Lukyanovich,

who paid for the salvation of a little girl in Berlin with his life. The

source for this version is the book Berlin 896 km by Soviet journalist and writer Boris Polewoi.

some 6,500 were confined at the outbreak of the war. Shortly thereafter, in September 1939, 900 Polish and stateless Jews from the Berlin area were taken to the camp; at the beginning of November, 500 Poles were interned. At the end of that month, 1,200 Czech students were added, and approximately 17,000 persons, mainly Polish nationals, were admitted as inmates in the period from March to September 1940. Despite the high number of new inmates, the camp population here too stabilised at the level of roughly 10,000 prisoners. That was because of the high mortality rate as well as the transfer of large numbers of Poles to Flossenbürg, Dachau, Neuengamme (in the Bergedorf section of southeastern Hamburg), and Groß-Rosen.

Sofsky (35)

In 1941 Dr. Lewe came to Sachsenhausen from the Buchenwald camp to take charge of the pathology department. Being camp senior, I was told that blocke seniors had to report inmates with unusual tattoos. This report was passed onto the roll call leader. Eventually, each of the tattooed inmates was ordered to come to the sickbay. Soon after we'd receive a death notice. Several times I went to the pathology department while Dr. Lewe wasn't there and in his room saw pieces of skin and body parts with these tattoos, which were kept in jars of alchol lining the walls. In the drawers too, prepared sections of skin were kept. I have held such sections of skin with my own hand.

The Russians, accompanied by Polish soldiers, chanced upon Sachsenhausen concentration camp as they moved to invest Berlin. The camp was in Oranienburg, and the fall of that former royal borough brought it home to Hitler that his days were numbered. There were just 5,000 prisoners left in Sachsenhausen of a population that had reached 50,000. The rest had been taken on 'death marches.’(58) After the Reich - The Brutal History of the Allied Occupation

More and more Berliners had been taking the risk of listening to the BBC on the wireless and even dared to discuss its news. But power cuts were now creating a more effective censorship of foreign broadcasts than the police state had ever achieved. London had little idea of the great Soviet offensive, but its announcement that Sachsenhausen- Oranienburg concentration camp had been liberated just north of Berlin gave a good idea of Red Army progress and its intention to encircle the city. The indication of the horrors found there was also another reminder of the vengeance which Berlin faced. This did not stop most Berliners from convincing themselves that the concentration camp stories must be enemy propaganda.

Beevor (274)

This representation speaks to the importance of international unity — a cornerstone of communist ideology — but lacks regard for any victim groups that were persecuted so harshly at the camps. There is no implied or overt reference to Jews, Sinti or Roma, homosexuals, Slavs, women, or Jehovah’s Witnesses, though all of these groups suffered explicit mass murders in the camp at Sachsenhausen based singularly on these identities. Indeed, many of these captives may have been Communists, but unless they identified as such, they were excluded from memory at the Tower of Nations.

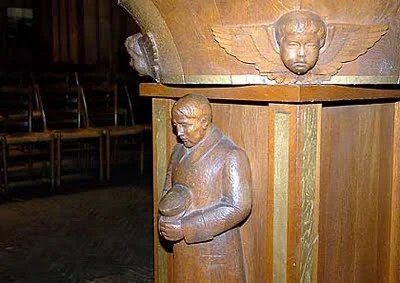

In front of Professor Waldemar Grzimek's bronze sculpture, Pietá,

depicting three figures who are supposed to symbolise resistance and

awareness of victory, mourning and death and as it appeared in 1961

before being given an English inscription. This memorial was limited to

the area of the former prisoner camp and only covered around five

percent of the area of the former concentration camp. Only “Station Z”

and the firing trench, originally part of the industrial courtyard,

were integrated into the memorial by relocating the camp wall. The

figures are notably more skeletal in nature than those at the obelisk, offering a much truer

representation of what inmates would have looked like after significant

time in the camp. Two of the prisoners are helping a fallen comrade, carrying him in a

blanket. The bronze cluster still speaks to the GDR message of

camaraderie, but in a more subdued and less overtly nationalist tone. Station

Z is a relevant place for mourning, and the

statue group reflects this, but allowed for a distinct and deliberate

division between areas of celebration and sorrow at the memorial site.

This is where the cremation ovens were located, where around 13,000 to

18,000 Soviet prisoners of war were murdered in the shot in the neck and

their corpses were then cremated.

In front of Professor Waldemar Grzimek's bronze sculpture, Pietá,

depicting three figures who are supposed to symbolise resistance and

awareness of victory, mourning and death and as it appeared in 1961

before being given an English inscription. This memorial was limited to

the area of the former prisoner camp and only covered around five

percent of the area of the former concentration camp. Only “Station Z”

and the firing trench, originally part of the industrial courtyard,

were integrated into the memorial by relocating the camp wall. The

figures are notably more skeletal in nature than those at the obelisk, offering a much truer

representation of what inmates would have looked like after significant

time in the camp. Two of the prisoners are helping a fallen comrade, carrying him in a

blanket. The bronze cluster still speaks to the GDR message of

camaraderie, but in a more subdued and less overtly nationalist tone. Station

Z is a relevant place for mourning, and the

statue group reflects this, but allowed for a distinct and deliberate

division between areas of celebration and sorrow at the memorial site.

This is where the cremation ovens were located, where around 13,000 to

18,000 Soviet prisoners of war were murdered in the shot in the neck and

their corpses were then cremated. Grzimek’s Pietá is not, however, without its limitations on historical representations. Though all the figures clearly are prisoners, and do depict a more historically accurate prisoner representation than those in Liberation, the man in the rear of the cluster, though wearing a look of grief on his face, stands tall, gaze fixed on a far off point, chest out and prideful. This is in contrast with many traditional representations of Pietá in which Mary is shown cradling the dead body of Jesus. Generally, the Pietá form is undeniably sorrowful. Mary has her head down, or tilted slightly up in supplication, and does not evoke any sense of physical strength or pride. Grzimek’s Pietá represents quite a different take on the classic form.

The NKVD’s interrogation of the camp commander Colonel Kainel confirmed that Senior Lieutenant Dzugashvili had been held three weeks in the camp prison and then, at Himmler’s directive, was transferred to the special camp, consisting of three barracks surrounded by a brick wall and high-voltage barbed wire. The inmates of barrack number 2 were allowed to walk in the early evening in the area outside their barracks. At 7:00 p.m., the ϟϟ guards ordered them to return to their barracks. All obeyed except Dzhugashvili, who demanded to see the camp commander. The guard’s repeated order went unheeded. As the ϟϟ guard telephoned the camp commander, he heard a shot and hung up. Dzhugashvili, in a state of agitation, had run across the neutral zone to the barbed wire. The guard raised his rifle ordering him to stop, but Dzugashvili kept on going. The guard warned that he was going to shoot; Dzhugashvili cursed, grabbed for the barbed-wire gate, and shouted at the guard to shoot. The guard shot him in the head and killed him. Clearly the unauthorised shooting of none other than Stalin’s son set off great apprehension in Sachsenhausen. He had been transferred in by Himmler himself, who hoped to use him as a pawn of some sort. Now, Stalin’s son was dead, and no one knew what the consequences would be. Dzhugashvili’s body lay stretched across the barbed wire for twenty-four hours while the camp awaited orders from Himmler. The Gestapo sent two professors to the scene who prepared a document stating that Dzhugashvili was killed by electrocution and that the shot to the head followed. The document stated that the guard acted properly. Dzhugashvili’s body was then burned, and the urn with his ashes was sent to the Gestapo headquarters. Indeed, it seemed irrelevant whether Yakov was killed by electrocution or by the bullet. Either way, it was he who committed suicide.Paul Gregory (65-66) Lenin's Brain

UFA Studios

In March 1937, using precisely the methods that he had previously branded as Jewish, Goebbels took over the major Ufa film company for the Reich. As a warning to Ufa he had instructed the press to trash its latest production; the film flopped disastrously, and the company agreed to sell out. ‘Today we buy up Ufa,’ recorded Goebbels, ‘and thus we [the propaganda ministry] are the biggest film, press, theatre, and radio concern in the world.’ Dismissing the entire Ufa board, he began to intervene in film production at every level, dismissing directors, recommending actresses (like the fiery Spaniard, Imperio Argentina), forcing through innovations like colour cinematography, and rationalising screen-test facilities for all three major studios, Ufa, Tobis, and Bavaria. Depriving the distributors of any such in such matters he created instead artistic boards to steer future film production. Suddenly the film industry began to surge ahead. Blockbuster films swept the box offices. With a sure touch, Goebbels stopped the production of pure propaganda and party epics, opting for more subtle messages instead—the wholesome family, the life well spent.Irving (414-415) Goebbels

In

late April 1945, the UFA ateliers in Potsdam-Babelsberg and

Berlin-Tempelhof were occupied by the Red Army. After Germany's

unconditional surrender the following month the Military Government Law

No. 191 initially halted and prohibited all further film production. On

July 14, 1945, as a result of Military Government Law No. 52, all

Reich-owned film assets of UFI Holding were seized. All activities in

the film industry were placed under strict licensing regulations and all

films were subject to censorship. The Soviet military government, which

was in favour of a speedy reconstruction of the German film industry

under Soviet supervision, incorporated the Babelsberg ateliers into

DEFA, subsequently the DDR's state film studio, on May 17, 1946. Murderers Among Us was

the first German feature film in the post-war era and the first

so-called "Trümmerfilm" ("Rubble Film"). It was shot here in Babelsberg.

Additionally, the Soviets confiscated numerous UFA productions from the

Babelsburg vaults and dubbed them into Russian for release in the USSR;

and simultaneously began importing Soviet films to the same offices for

dubbing into German and distribution to the surviving German theatres.

In contrast, the main film-policy goal of the Allied occupying forces,

under American insistence, consisted in preventing any future

accumulation of power in the German film industry. Here I'm beside the

statue based on the Portaprima Augustus for the execrable 1997 film Prince Valiant.

In

late April 1945, the UFA ateliers in Potsdam-Babelsberg and

Berlin-Tempelhof were occupied by the Red Army. After Germany's

unconditional surrender the following month the Military Government Law

No. 191 initially halted and prohibited all further film production. On

July 14, 1945, as a result of Military Government Law No. 52, all

Reich-owned film assets of UFI Holding were seized. All activities in

the film industry were placed under strict licensing regulations and all

films were subject to censorship. The Soviet military government, which

was in favour of a speedy reconstruction of the German film industry

under Soviet supervision, incorporated the Babelsberg ateliers into

DEFA, subsequently the DDR's state film studio, on May 17, 1946. Murderers Among Us was

the first German feature film in the post-war era and the first

so-called "Trümmerfilm" ("Rubble Film"). It was shot here in Babelsberg.

Additionally, the Soviets confiscated numerous UFA productions from the

Babelsburg vaults and dubbed them into Russian for release in the USSR;

and simultaneously began importing Soviet films to the same offices for

dubbing into German and distribution to the surviving German theatres.

In contrast, the main film-policy goal of the Allied occupying forces,

under American insistence, consisted in preventing any future

accumulation of power in the German film industry. Here I'm beside the

statue based on the Portaprima Augustus for the execrable 1997 film Prince Valiant.  With

the establishment of the Wehrmacht in 1935, the fort became a training

location again and was expanded. After the war parts of the brick walls

and structures were broken up to make the fort unusable as a military

installation by blowing up the moat defences. The rubble was transported away as building material for the reconstruction of Berlin as residents

were given permission to demolish the Escarpemauer and other components

for material extraction for the repair of destroyed buildings or for the

construction of new houses. Before

the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, the fort was located at the border

crossing point on Heerstraße and was only been accessible to the public

again since 1990. The Nazi eagle above the entrance has been allowed to remain.

With

the establishment of the Wehrmacht in 1935, the fort became a training

location again and was expanded. After the war parts of the brick walls

and structures were broken up to make the fort unusable as a military

installation by blowing up the moat defences. The rubble was transported away as building material for the reconstruction of Berlin as residents

were given permission to demolish the Escarpemauer and other components

for material extraction for the repair of destroyed buildings or for the

construction of new houses. Before

the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, the fort was located at the border

crossing point on Heerstraße and was only been accessible to the public

again since 1990. The Nazi eagle above the entrance has been allowed to remain.  The fort and area around were used as the hideout forest for the Inglorious Basterds.

As an aside, the title of the movie has to have the swastika removed

because the display of Nazi iconography is illegal in Germany. The

"Offizielle deutsche Website"

has been censored too. Under the German law there are exceptions which

allow the use of "unconstitutional symbols" for artistic and

educational purposes but Universal Pictures obviously didn't find it

worth the effort.

The fort and area around were used as the hideout forest for the Inglorious Basterds.

As an aside, the title of the movie has to have the swastika removed

because the display of Nazi iconography is illegal in Germany. The

"Offizielle deutsche Website"

has been censored too. Under the German law there are exceptions which

allow the use of "unconstitutional symbols" for artistic and

educational purposes but Universal Pictures obviously didn't find it

worth the effort.See: Television Under The Swastika (English Version)

Recently uncovered footage, long buried in East German archives, confirms that television's first revolution occurred under the Third Reich. From 1935 to 1944, Berlin studios churned out the world's first regular TV programming, replete with the evening news, street interviews, sports coverage, racial programs, and interviews with Nazi officials. Select audiences, gathered in television parlours across Germany, numbered in the thousands; plans to create a mass viewing public, through the distribution of 10,000 people's television sets, were upended by World War Two. German technicians achieved remarkable breakthroughs in televising live events, including near instantaneous broadcasts of the 1936 Olympic Games. At the same time, the demand for continuous programming opened up camera opportunities far less controlled, and more candidly revealing, than Third Reich propagandists would have liked (an interview with a bumbling Robert Ley is particularly embarrassing). In its stated mission - to imprint the image of the Führer onto every German heart - Nazi television proved a major disappointment. But its surviving footage - 285 rolls have been found so far offers an intriguing new window onto Hitler's Germany.

Joseph Wackerle's reichsadler dating from 1935 remains in situ

although Siemens itself has left. With the war, Germany's demand for

armaments began to intensify. Without the aid of foreign workers, the

manufacturing sector could no longer meet this demand which only grew

given that growing numbers of qualified employees at the company’s

various plants were drafted for military service. This led to the

increased use of forced labour starting in 1940 when Siemens relied

increasingly on forced labourers to maintain production levels. These

labourers included people from territories occupied by the German

military, PoWs, Jews, Sinti, Roma and, in the final phases of the war,

concentration camp inmates. During the entire period from 1940 to 1945,

at least eighty thousands of forced labourers worked at Siemens.

Although the company’s production of weapons and ammunition was rather

limited, from the end of 1943 onwards Siemens primarily manufactured

electrical equipment for the armed forces.

Joseph Wackerle's reichsadler dating from 1935 remains in situ

although Siemens itself has left. With the war, Germany's demand for

armaments began to intensify. Without the aid of foreign workers, the

manufacturing sector could no longer meet this demand which only grew

given that growing numbers of qualified employees at the company’s

various plants were drafted for military service. This led to the

increased use of forced labour starting in 1940 when Siemens relied

increasingly on forced labourers to maintain production levels. These

labourers included people from territories occupied by the German

military, PoWs, Jews, Sinti, Roma and, in the final phases of the war,

concentration camp inmates. During the entire period from 1940 to 1945,

at least eighty thousands of forced labourers worked at Siemens.

Although the company’s production of weapons and ammunition was rather

limited, from the end of 1943 onwards Siemens primarily manufactured

electrical equipment for the armed forces.  Following

the war all of Siemens's factories in Berlin were closed after nearly

half its buildings and production facilities had been destroyed.

Whatever remained – the large number of functional machines, the

company’s entire inventory, a large portion of its stock and finished

goods as well as technical documentation and design drawings – was

dismantled and removed by the Soviet army as war reparations.The Allies

confiscated all the company’s tangible assets worldwide and all its

trademark and patent rights were rescinded. All its foreign assets were

lost. Overall, Siemens forfeited 80% of its total worth or some 2.6 billion German marks.

Following

the war all of Siemens's factories in Berlin were closed after nearly

half its buildings and production facilities had been destroyed.

Whatever remained – the large number of functional machines, the

company’s entire inventory, a large portion of its stock and finished

goods as well as technical documentation and design drawings – was

dismantled and removed by the Soviet army as war reparations.The Allies

confiscated all the company’s tangible assets worldwide and all its

trademark and patent rights were rescinded. All its foreign assets were

lost. Overall, Siemens forfeited 80% of its total worth or some 2.6 billion German marks.

The Martin Luther Memorial Church, constructed between September 1933 and December 1935, stands as a significant architectural and historical artefact of the Third Reich’s influence on religious spaces. Designed by architect Curt Steinberg, a member of the Nazi Party since 1933, the church was erected in the Mariendorf district to accommodate a growing congregation that had been planning a new place of worship since 1885. The structure, completed in a Bauhaus-influenced style with its stark brick and stone exterior, was deliberately infused with National Socialist ideology, evident in its interior decorations and symbolic elements. The church’s inauguration on December 22, 1935, marked a moment where Nazi anthems were sung alongside traditional Christian hymns, reflecting the fusion of political and religious ideologies promoted by the German Christian movement. This group, led by Joachim Hossenfelder, sought to align Protestantism with Nazi principles, earning the moniker “stormtroopers of Jesus” in a sermon delivered by Hossenfelder on July 23, 1933, during a campaign to influence church elections.

The interior of the church was meticulously crafted to reflect this ideological synthesis. The vestibule, designed as a hall of honour for World War I soldiers, featured a chandelier shaped like an iron cross, casting light on busts of Martin Luther and Hindenburg. Until 1945, a bust of Hitler himself was displayed alongside these figures, a detail confirmed by church dean Isolde Boehm in a statement made on April 21, 2006. The hymn “A Mighty Fortress Is Our God,” inscribed in German around the vestibule, was co-opted into a nationalistic narrative, transforming a traditional Protestant anthem into a symbol of Nazi-aligned fervour. The main sanctuary, designed to seat 800 worshippers, contained a massive stone archway adorned with approximately 800 terracotta panels. These panels juxtaposed Christian symbols, such as crosses, with imagery of workers, soldiers, and eagles, some of which originally bore swastikas until their removal post-1945 due to legal prohibitions on Nazi symbols in Germany.

The altar presented a striking depiction of Jesus, carved as a muscular figure with a raised chin, embodying strength and defiance rather than traditional Christian humility. This portrayal, noted by historian Ilse Klein on April 21, 2006, was intended to project a “German hero” aligned with fascist ideals of power and victory. The baptismal font, carved from oak, featured a family scene with a mother, child, and father dressed as an SA stormtrooper, symbolising the idealised Nazi family unit. The pulpit further reinforced this narrative, with carvings depicting Jesus preaching alongside figures of a soldier, an SA member, and a Hitler Youth, blending religious reverence with militaristic and political allegiance. These elements were not incidental but part of a deliberate design to merge Christian theology with Nazi ideology, a goal articulated by the German Christians’ campaign in July 1933 to “merge Christ’s cross with the hooked cross,” as stated in a propaganda poster from that election.

The church’s organ, a grand Walcker instrument, carried a particularly dark legacy. Before its installation in the church, it was played at the Nazi Party rally in Nuremberg on September 10, 1935, where the antisemitic Nuremberg Laws were announced. The organ’s façade, painted with folkloric motifs, was unveiled during the church’s opening ceremony, amplifying the event’s ideological weight. The bells, embossed with swastikas, rang to summon worshippers until their removal in 1942, when metal shortages necessitated their repurposing for the war effort. These bells, cast in March 1933, were a gift from the local Nazi Party branch, as recorded in parish records from that year. The church’s design and furnishings were thus not merely decorative but served as propaganda tools, embedding Nazi ideology into the fabric of religious life.

Despite its overt alignment with National Socialism, the church also witnessed acts of resistance. Pastor Max Kurzreiter, who served from 1935 to 1945, performed a clandestine marriage on March 15, 1938, between writer Jochen Klepper and his Jewish wife, Johanna. This union, illegal under Nazi racial laws, demonstrated Kurzreiter’s defiance, though it came at great personal risk. Tragically, Klepper, Johanna, and their daughter took their own lives on December 11, 1942, to avoid deportation after Adolf Eichmann denied their visa application on November 20, 1942. This event, documented in church records, underscores the complex interplay of complicity and resistance within the institution. The parish’s membership, with two-thirds registered as Nazi Party members by January 1934, reflected the broader societal penetration of Nazi ideology, yet individual acts like Kurzreiter’s highlight exceptions to this trend.

The German Christian movement, which dominated the church’s early years, was formalised under the Protestant Reich Church, established on July 11, 1933, under Ludwig Müller’s leadership. Müller, appointed Reich Bishop on September 27, 1933, advocated for a Christianity stripped of “Jewish influence,” including the removal of the Old Testament from church teachings, as declared in a public appeal on January 5, 1934. This appeal stated, “The eternal God created a law peculiar to our nation in Adolf Hitler,” encapsulating the movement’s attempt to sanctify Nazi leadership. The Martin Luther Memorial Church became a physical manifestation of this ideology, with its architecture and iconography designed to glorify both Christ and the Führer. Proposals in 1933 to name the church after Adolf Hitler, as noted by Isolde Boehm, were ultimately rejected, but the suggestion itself reveals the extent of Nazi influence over the congregation.

The church’s role as a site of Nazi propaganda was further evident in its use during key events. On November 10, 1933, the 450th anniversary of Martin Luther’s birth was celebrated as “German Luther Day,” with a speech by Joachim Hossenfelder at the church praising Luther as a “spiritual Führer” whose ideas unified German Christianity. This event, attended by 600 congregants, was reported in the Chemnitzer Tageblatt on November 11, 1933, as a moment of national and religious renewal.

After the war the church underwent significant changes to address its Nazi legacy. The swastika-embossed bells were melted down by July 1942, and the Hitler bust was replaced with one of Martin Luther by August 1945. The swastikas on the terracotta panels were chiselled out between June and September 1945, leaving blank spaces as a testament to denazification efforts. In 1970, new stained-glass windows by Hans Gottfried von Stockhausen, depicting the Holy Communion liturgy, were installed to replace originals destroyed in a bombing raid on November 23, 1943.

“There was a bust of Adolf Hitler in the nave,” Isolde Boehm, dean of

the church, said. “A carved face of Hitler has been replaced by one of

Martin Luther. There is even a rumour that the church was supposed to

be called the Adolf Hitler Church.”

There

is no other church in Germany so obviously from the Third Reich era. In

the 1930s two thirds of the parish of Martin Luther Memorial were Nazi

Party members. Their babies were baptised in a wooden font, which

still bears the image of a storm trooper, and they married to music

played by an organ that helped to create the dark atmosphere of the

Nuremberg rallies. In 1932 the Protestant church came under the

influence of a Nazi movement called the "German Christians" -- called

"stormtroopers of Jesus," by the group's leader and founder Rev.

Joachim Hossenfelder. In 1933 Hitler forced regional Protestant churches

to merge into the Protestant Reich Church which, based on Nazi ideas

of “positive Christianity”, portrayed Jesus as an “Aryan” and

eliminated the Old Testament.

During the war Alfred Rosenberg conceived a new National Reich Church

which would replace the Bible with Mein Kampf. Until 1942 bells

embossed with the swastika called the Nazi faithful to church on

Sundays. Then the bells were melted down and made into cannon.

Parishioners and priests are trying to raise the €3.5 million needed to rescue the church from collapse. Sources: Der Spiegel and The Times on Line

Charlottenburg

Palace, the largest palace in Berlin and the only royal residency

in the city dating back to the time of the Hohenzollern family. During

thewar the palace was badly damaged but has since been

reconstructed with Andreas Schlüter’s epic Reiterdenkmal

des Grossen Kurfürsten of 1699 which shows the

Great Elector on horseback, also returned to

the front courtyard.

Charlottenburg

Palace, the largest palace in Berlin and the only royal residency

in the city dating back to the time of the Hohenzollern family. During

thewar the palace was badly damaged but has since been

reconstructed with Andreas Schlüter’s epic Reiterdenkmal

des Grossen Kurfürsten of 1699 which shows the

Great Elector on horseback, also returned to

the front courtyard. Charlottenburg, where the journalist Margret Boveri lived, was an affluent area, and one of the last to surrender. She became aware of the change in the situation when she ventured out on to the streets to obtain her last quarter-pound of butter. She found Russians already sniffing at the queues. Most of the Berliners had thought it prudent to don white armbands. They openly complained of the Party for the first time. When she got home she found that German soldiers had broken into a neighbour’s cellar to steal civilian clothes. They intended to make a break for the west: no one wanted to be caught by the Russians. ... The terror began quietly in Margret Boveri’s Charlottenburg. ‘Ich Pistol!’ announced the soldiers. ‘Du Papier!’ That meant that they had guns, and no amount of paperwork was going to do you any good if you wanted to hang on to property or virtue. ‘There is nothing in this city that isn’t theirs for the taking,’ reported another woman who lived near Neukölln in the south. At first the Russian soldiers came for watches. With a cry of ‘Uhri! Uhri!’ they snatched, sometimes discarding the previous acquisition, which had simply stopped and needed to be rewound. This anonymous ‘Woman’ saw many Red Army soldiers with whole rows of watches on their arms ‘which they continuously kept winding, comparing and correcting – with childish, thievish pleasure’.. Most of the rapists in Charlottenburg, Margret Boveri discovered, were simple soldiers sleeping rough in the park. Those who had been properly billeted behaved better. She resorted to sleeping pills to get though the night, and didn’t wake when the Russians knocked at her door. Only in the morning did she hear the grim news from the neighbours.

MacDonogh, After the Reich

It was he who designed the memorial to the 'martyrs' of November 9, 1923 in the Feldherrnhalle, the eagles that were installed atop the party buildings in Munich, on the Nazi Party Rally Grounds in Nuremberg and the eagle relief that was seen in the smoking room in the New Reich Chancellery.

Schmid-Ehmen made the nine-metre high bronze eagle for the German

Pavilion at the 1937 World Exhibition in Paris referred to above and

received the Grand Prix de la Republique Française for it. From 1936 he

was a member of the Presidential Council of the Reich Chamber of Fine

Arts, and on January 30, 1937 Hitler appointed him professor. In 1938

Hitler bought his Spear bearer. In 1939 Schmid-Ehmen was represented at

the Great German Art Exhibition in the House of German Art in Munich

with the bronze sculpture 'Mädchen mit Zweig'.

It was he who designed the memorial to the 'martyrs' of November 9, 1923 in the Feldherrnhalle, the eagles that were installed atop the party buildings in Munich, on the Nazi Party Rally Grounds in Nuremberg and the eagle relief that was seen in the smoking room in the New Reich Chancellery.

Schmid-Ehmen made the nine-metre high bronze eagle for the German

Pavilion at the 1937 World Exhibition in Paris referred to above and

received the Grand Prix de la Republique Française for it. From 1936 he

was a member of the Presidential Council of the Reich Chamber of Fine

Arts, and on January 30, 1937 Hitler appointed him professor. In 1938

Hitler bought his Spear bearer. In 1939 Schmid-Ehmen was represented at

the Great German Art Exhibition in the House of German Art in Munich

with the bronze sculpture 'Mädchen mit Zweig'.

Schubertstraße in Lichterfelde, hit by the RAF on the night of January 28/29 1945, after the war and today

In

the 1930s, Tempelhof was at the forefront of European air traffic with

its traffic volume, ahead of Paris, Amsterdam and even London. The

limits of the technical possibilities were soon reached, and in January

1934 the first planning work for a new building for a large airport on

the Tempelhofer Feld began. In July 1935, the architect Ernst Sagebiel

received the planning order for the new building from the Reich Aviation

Ministry, which reflected both the new urban planning ideas and the

monumental architecture under the Nazis and had to anticipate the

development of aviation for a longer period of time. The airport was

planned to handle up to six million passengers a year. The facility was

intended not only for air traffic, but also serve for events such as the

Reichsflugtag and provide a seat for as many aviation-related agencies

and institutions as possible. This new building also met all the

requirements of a military airfield at the time.

In

the 1930s, Tempelhof was at the forefront of European air traffic with

its traffic volume, ahead of Paris, Amsterdam and even London. The

limits of the technical possibilities were soon reached, and in January

1934 the first planning work for a new building for a large airport on

the Tempelhofer Feld began. In July 1935, the architect Ernst Sagebiel

received the planning order for the new building from the Reich Aviation

Ministry, which reflected both the new urban planning ideas and the

monumental architecture under the Nazis and had to anticipate the

development of aviation for a longer period of time. The airport was

planned to handle up to six million passengers a year. The facility was

intended not only for air traffic, but also serve for events such as the

Reichsflugtag and provide a seat for as many aviation-related agencies

and institutions as possible. This new building also met all the

requirements of a military airfield at the time.  |

| Hitler and Göring at Tempelhof, 1932 |

When the front approached at the end of April 1945, the airport was to

be defended. The airport commander at the time, Colonel Rudolf Böttger,

and some senior Lufthansa employees circumvented this order, however, by

having the weapons provided and setting up a field hospital. This did

not lead to a defence of the airport, which could have led to its

complete destruction. According to Wikipedia, Böttger evaded Adolf

Hitler's extermination order to blow up the entire complex by suicide.

However, according to other sources he was called upon by an officer of

the Waffen ϟϟ

for insubordination and shot. In fact, the concrete floor of the main

hall was blown up, so that it fell onto the luggage level below and the

main hall became unusable. On April 29 1945 Red Army troops occupied the

Tempelhof district and the airport. The new buildings were largely

spared from destruction, but there were several fires that also severely

damaged the steel structure of the hall buildings. The buildings of the

old airport were completely destroyed and the airfield was littered

with impacts. The underground bunker with the film archive also burned

down completely, and all films were destroyed in the process.

When the front approached at the end of April 1945, the airport was to

be defended. The airport commander at the time, Colonel Rudolf Böttger,

and some senior Lufthansa employees circumvented this order, however, by

having the weapons provided and setting up a field hospital. This did

not lead to a defence of the airport, which could have led to its

complete destruction. According to Wikipedia, Böttger evaded Adolf

Hitler's extermination order to blow up the entire complex by suicide.

However, according to other sources he was called upon by an officer of

the Waffen ϟϟ

for insubordination and shot. In fact, the concrete floor of the main

hall was blown up, so that it fell onto the luggage level below and the

main hall became unusable. On April 29 1945 Red Army troops occupied the

Tempelhof district and the airport. The new buildings were largely

spared from destruction, but there were several fires that also severely

damaged the steel structure of the hall buildings. The buildings of the

old airport were completely destroyed and the airfield was littered

with impacts. The underground bunker with the film archive also burned

down completely, and all films were destroyed in the process. Nearby, Volkssturm along Hermannstrasse. Beevor (302) writes of how

The remnants of his `Norge' and `Danmark' regiments were waiting impatiently by the canal for motor transport, which was having difficulty getting to them through the rubble-blocked streets. Just as the trucks finally arrived, a cry of alarm was heard: `Panzer durchgebrochen!' This cry prompted a surge of `tank fright' even among hardened veterans and a chaotic rush for the vehicles, which presented an easy target for the two T-34s that had broken through. The trucks that got away even had men clinging on to the outsides. As they escaped north up the Hermannstrasse, they saw scrawled on a house wall `SS traitors extending the war!' There was no doubt in their minds as to the culprits: `German Communists at work. Were we going to have to fight against the enemy within as well?

.gif)