Nazi Housing Development

The

government of Chancellor Brüning in 1931 established the small

settlement programme in order "to promote the population becoming

settled in the country to reduce unemployment and to facilitate

sufficient living conditions for the unemployed." The future settlers

were to be involved in the establishment of their own homes and gardens

and small animal husbandry to improve their supply in the economic

crisis. The Nazis took over the model because it fit into their

anti-modern and anti-urban ideology. This served as the basis for a senior's research investigation which received a top mark from the IBO:

Was housing policy in Germany affected by the change of government in 1933?

The Nazi Siedlung at Kurfürstenplatz was constructed between April 1938 and September 1940, serving as a residential complex designed to provide housing for Nazi Party affiliates, particularly mid-ranking officials and their families. Situated in the Schwabing district, the settlement was part of a broader Nazi initiative to create ideologically aligned communities that reflected the regime’s Blut und Boden ideology, which emphasised a connection between the German people and their land. The project was overseen by the Deutsche Arbeitsfront (DAF), the Nazi labour organisation, and designed by architect Hans Atzenbeck, a graduate engineer known for his work on functional urban developments. The settlement’s construction cost approximately 1.5 million Reichsmarks with funding provided through the Reichsministerium für Rüstung und Kriegsproduktion. The Kurfürstenplatz Siedlung comprised 37 residential units, primarily 2½- to 3½-room flats, arranged in a series of low-rise blocks around a central courtyard. The architectural style adhered to the Heimatschutzstil, a Nazi-preferred aesthetic that promoted traditional Germanic elements such as steep-pitched roofs, timber framing, and brick façades. Each unit included a small garden to encourage self-sufficiency, aligning with Nazi policies of autarky. The site also incorporated a savings bank branch and a police office, reflecting its role as a self-contained community hub. The buildings were constructed using local materials, primarily brick and timber, to comply with the regime’s economic self-reliance directives. The settlement covered approximately 3 hectares, strategically located near Munich’s city centre to ensure accessibility for Party officials.

The Nazi Siedlung at Kurfürstenplatz was constructed between April 1938 and September 1940, serving as a residential complex designed to provide housing for Nazi Party affiliates, particularly mid-ranking officials and their families. Situated in the Schwabing district, the settlement was part of a broader Nazi initiative to create ideologically aligned communities that reflected the regime’s Blut und Boden ideology, which emphasised a connection between the German people and their land. The project was overseen by the Deutsche Arbeitsfront (DAF), the Nazi labour organisation, and designed by architect Hans Atzenbeck, a graduate engineer known for his work on functional urban developments. The settlement’s construction cost approximately 1.5 million Reichsmarks with funding provided through the Reichsministerium für Rüstung und Kriegsproduktion. The Kurfürstenplatz Siedlung comprised 37 residential units, primarily 2½- to 3½-room flats, arranged in a series of low-rise blocks around a central courtyard. The architectural style adhered to the Heimatschutzstil, a Nazi-preferred aesthetic that promoted traditional Germanic elements such as steep-pitched roofs, timber framing, and brick façades. Each unit included a small garden to encourage self-sufficiency, aligning with Nazi policies of autarky. The site also incorporated a savings bank branch and a police office, reflecting its role as a self-contained community hub. The buildings were constructed using local materials, primarily brick and timber, to comply with the regime’s economic self-reliance directives. The settlement covered approximately 3 hectares, strategically located near Munich’s city centre to ensure accessibility for Party officials.

The site on February 26, 1938 when it was officially opened by Munich’s mayor, Karl Fiehler, who highlighted the project’s role in addressing housing shortages and enhancing urban design.

It was reported at the time that

[t]he topping-out ceremony for the new residential buildings of the Städtische Sparkasse, which will also include new rooms for the Sparkasse branch and the northern police section, will take place on Kurfürstenplatz Mayor Fiehler then points out that a number of needs resulted in the need for the new building, such as the space requirements of the savings bank, the police, the creation of apartments and the necessary redesign of the square to create an appealing urban design.

Archaeological investigations conducted by the Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München between May 2006 and July 2008 uncovered artefacts including Nazi Party badges, household items with swastika markings, and architectural plans detailing the settlement’s layout. A report in the Zeitschrift für Bayerische Landesgeschichte from February 2009 noted the discovery of a small underground storage facility beneath one of the buildings, likely used for Party documents or emergency supplies. Soil analysis confirmed no evidence of wartime violence or burials on-site, distinguishing it from other Nazi-era locations associated with atrocities.

After the war, the American military administration confiscated the Kurfürstenplatz Siedlung on December 4, 1945, to house displaced persons under the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA).

Approximately 2,000 individuals, including Jewish refugees from Eastern Europe, were temporarily accommodated there. Former residents, primarily Nazi affiliates, were relocated by the Munich housing office. By June 1949, most original occupants had returned, though Nazi symbols were removed from the buildings by April 1946 under Allied orders. The Munich Senate debated demolition on October 15, 1951, but opted to preserve the site due to the post-war housing shortage, as noted in the Stadtarchiv München. The settlement remained largely undamaged during the war. Today, the buildings are privately owned and used as residential flats, with no visible traces of their Nazi origins helped by Google

Street view which blocks the image of the entire building! Google

isn't known for respecting privacy, so could this have been pushed by

the authorities given the remaining Nazi-era reliefs?

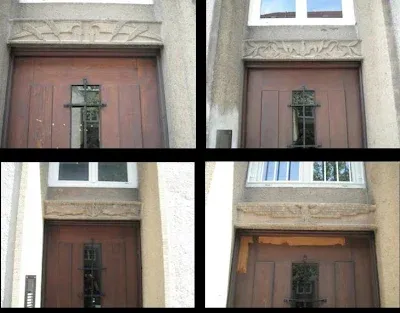

These

siedlung on Klugstrasse all have bizarre Third Reich, astrological,

masonic, and other obscure symbols over every door frame leading inside.

To me, it's incredible that they continue to survive and form the

entrances to people's homes:

The swastika is still faintly visible...

...whilst this one, dated 1933, is obscured by the shaking hands

Here the hakenkreuz has been erased, but the Nazi salutes allowed to remain!

Another excised swastika that completed the DAF symbol

And yet a couple have had their bizarre symbols completely removed.

The

left image shows swords and a steel helmet whilst the one on the right

reminds me of the lesson from the Disney wartime cartoon Education for Death...

Construction of the Siedlung on Klugstraße in Munich’s Gern district commenced in 1933, with completion in time for Hitler's birthday by April 1934. Designed under the supervision of architect Hans Atzenbeck, the project formed part of the Third Reich’s broader housing initiative to provide affordable, ideologically aligned living spaces for the working class. The Klugstraße Siedlung, comprising multiple residential blocks, was intended to embody the Nazi concept of a Volksgemeinschaft, integrating communal spaces with state oversight. Each building featured multiple entrances, with flats ranging from two to four rooms, typically housing families employed in nearby industries or administrative roles. Ground floors included commercial spaces, such as small shops, to support self-sufficiency, while courtyards served as communal areas, often adorned with fountains or sculptures promoting Nazi ideals, such as depictions of idealised workers or youth. Unlike the Kurfürstenplatz Siedlung, the Klugstraße development is distinguished by its extensive use of symbolic reliefs above door frames, incorporating Third Reich iconography, astrological motifs, and alleged Masonic symbols.

Construction of the Siedlung on Klugstraße in Munich’s Gern district commenced in 1933, with completion in time for Hitler's birthday by April 1934. Designed under the supervision of architect Hans Atzenbeck, the project formed part of the Third Reich’s broader housing initiative to provide affordable, ideologically aligned living spaces for the working class. The Klugstraße Siedlung, comprising multiple residential blocks, was intended to embody the Nazi concept of a Volksgemeinschaft, integrating communal spaces with state oversight. Each building featured multiple entrances, with flats ranging from two to four rooms, typically housing families employed in nearby industries or administrative roles. Ground floors included commercial spaces, such as small shops, to support self-sufficiency, while courtyards served as communal areas, often adorned with fountains or sculptures promoting Nazi ideals, such as depictions of idealised workers or youth. Unlike the Kurfürstenplatz Siedlung, the Klugstraße development is distinguished by its extensive use of symbolic reliefs above door frames, incorporating Third Reich iconography, astrological motifs, and alleged Masonic symbols.  These door frame reliefs include swastikas, some faintly visible or partially erased post-1945, alongside motifs such as swords, steel helmets, and clasped hands, which were associated with the Deutsche Arbeitsfront, the Nazi labour organisation. Astrological symbols, including zodiac signs like Aries or Scorpio, appear in several instances, possibly reflecting the regime’s interest in esoteric imagery to evoke a sense of cosmic destiny, as discussed in studies by Nicholas Goodrick-Clarke on Nazi occultism. Alleged Masonic symbols, such as squares, compasses, or all-seeing eyes, are less conclusively identified but have been debated due to their resemblance to traditional Masonic iconography. These symbols survived post-war efforts to remove Nazi imagery, likely due to their integration into the architectural fabric and the complexity of erasing intricate stonework. Some reliefs, particularly those with swastikas, were defaced or covered, whilst others, like the DAF’s clasped hands dated 1933, remain intact, as shown in my pics.

These door frame reliefs include swastikas, some faintly visible or partially erased post-1945, alongside motifs such as swords, steel helmets, and clasped hands, which were associated with the Deutsche Arbeitsfront, the Nazi labour organisation. Astrological symbols, including zodiac signs like Aries or Scorpio, appear in several instances, possibly reflecting the regime’s interest in esoteric imagery to evoke a sense of cosmic destiny, as discussed in studies by Nicholas Goodrick-Clarke on Nazi occultism. Alleged Masonic symbols, such as squares, compasses, or all-seeing eyes, are less conclusively identified but have been debated due to their resemblance to traditional Masonic iconography. These symbols survived post-war efforts to remove Nazi imagery, likely due to their integration into the architectural fabric and the complexity of erasing intricate stonework. Some reliefs, particularly those with swastikas, were defaced or covered, whilst others, like the DAF’s clasped hands dated 1933, remain intact, as shown in my pics.  The integration of astrological and alleged Masonic symbols in the Klugstraße Siedlung is particularly intriguing given the Third Reich’s complex relationship with Freemasonry. Freemasonry was banned in 1934 under the Enabling Act, with lodges dissolved and assets confiscated. Nazi propaganda, led by figures like Reinhard Heydrich, linked Freemasonry to a supposed “Jewish-Masonic conspiracy,” accusing it of undermining German nationalism. Despite this, some Nazi architects incorporated symbols resembling Masonic iconography, possibly as a subversive nod or due to their aesthetic appeal, as suggested by historian Wolfgang Schäche. Indeed, Eric Kurlander writes how

The integration of astrological and alleged Masonic symbols in the Klugstraße Siedlung is particularly intriguing given the Third Reich’s complex relationship with Freemasonry. Freemasonry was banned in 1934 under the Enabling Act, with lodges dissolved and assets confiscated. Nazi propaganda, led by figures like Reinhard Heydrich, linked Freemasonry to a supposed “Jewish-Masonic conspiracy,” accusing it of undermining German nationalism. Despite this, some Nazi architects incorporated symbols resembling Masonic iconography, possibly as a subversive nod or due to their aesthetic appeal, as suggested by historian Wolfgang Schäche. Indeed, Eric Kurlander writes how Unlike many Nazis, for example, Hitler expressed relatively little interest inthe dangers of freemasonry. But he did admire their ‘esoteric doctrine’, accordingto Rauschning, ‘imparted through the medium of symbols and mysterious ritesin degrees of initiation. The hierarchical organisation and the initiation throughsymbolic rites, that is to say without bothering the brains but by working on theimagination through magic and the symbols of a cult.' Whatever his reservations regarding ‘völkisch wandering scholars’, Hitler recognised the power of the supernatural imaginary in appealing both to his party colleagues and ordinary Germans.Hitler’s Monsters (59)

The astrological motifs may reflect the influence of figures like Himmler, who, according to Goodrick-Clarke, promoted esoteric ideologies within the ϟϟ. However, no primary sources explicitly confirm Masonic affiliations in the Klugstraße designs, and the symbols’ presence may instead stem from the regime’s appropriation of historical motifs to evoke authority, as seen in other Nazi architectural projects like the Luftwaffe headquarters.  Nevertheless, these specific symbols on Klugstraße façades include partially erased swastikas, dated 1933, and sig runes, which are linked to Himmler’s adoption of Guido von List’s Ariosophy, a racist-occultist ideology developed between 1890 and 1918. List’s work, particularly his 1908 book, The Secret of the Runes, reinterpreted runes as mystical markers of Aryan heritage, with the sig rune symbolising victory and solar power. On Klugstraße, sig runes appear above doorways, often arranged in pairs or radial patterns, evoking the Black Sun motif found at Wewelsburg Castle, where Himmler established an ϟϟ ideological centre on August 1, 1934. A surviving relief shown here depicts a swastika alongside a steel helmet and crossed swords, symbolising martial and cosmic order, which Goodrick-Clarke notes as reflective of Himmler’s belief in astrology as a guiding force for ϟϟ destiny. Another façade, dated displays a faintly visible swastika with clasped hands as a supposed symbol of communal unity under astrological auspices, specifically tied to Cancer’s influence on loyalty and kinship.

Nevertheless, these specific symbols on Klugstraße façades include partially erased swastikas, dated 1933, and sig runes, which are linked to Himmler’s adoption of Guido von List’s Ariosophy, a racist-occultist ideology developed between 1890 and 1918. List’s work, particularly his 1908 book, The Secret of the Runes, reinterpreted runes as mystical markers of Aryan heritage, with the sig rune symbolising victory and solar power. On Klugstraße, sig runes appear above doorways, often arranged in pairs or radial patterns, evoking the Black Sun motif found at Wewelsburg Castle, where Himmler established an ϟϟ ideological centre on August 1, 1934. A surviving relief shown here depicts a swastika alongside a steel helmet and crossed swords, symbolising martial and cosmic order, which Goodrick-Clarke notes as reflective of Himmler’s belief in astrology as a guiding force for ϟϟ destiny. Another façade, dated displays a faintly visible swastika with clasped hands as a supposed symbol of communal unity under astrological auspices, specifically tied to Cancer’s influence on loyalty and kinship.

Karl Maria Wiligut, Himmler’s esoteric advisor contributed to the Klugstraße iconography through his Irminist system, which blended Ariosophy with astrological interpretations of runes. Wiligut’s influence is documented in ϟϟ correspondence from May 15, 1935, where he advised on zodiacal alignments for ϟϟ rituals. One façade features the Odal rune, symbolising blood and soil, which Wiligut linked to Taurus, representing rootedness and racial purity. This rune appears on at least seven doorways, each accompanied by astrological glyphs, such as the Taurus symbol, carved into lintels. These carvings were intended to align the Siedlung’s inhabitants with cosmic cycles, as Wiligut claimed in a June 1936 memo to Himmler that such symbols would spiritually fortify Aryan communities.

The Klugstraße Siedlung also incorporates motifs inspired by Wilhelm Theodor H. Wulff, Himmler’s astrologer. Wulff’s 1973 book, Zodiac and Swastika, describes his consultations with Himmler, including a directive on January 10, 1943, to design ϟϟ symbols reflecting zodiacal harmony. One image shows a solar wheel with twelve spokes, resembling the Black Sun and aligned with Leo’s solar symbolism, which Wulff associated with ϟϟ leadership. This motif appears on five houses, reflecting solstice alignments. Goodrick-Clarke cites Wulff’s claim that Himmler requested such symbols to evoke a mystical connection to the Aryan past, with the Klugstraße designs mirroring Wewelsburg’s Black Sun mosaic.

The Klugstraße Siedlung also incorporates motifs inspired by Wilhelm Theodor H. Wulff, Himmler’s astrologer. Wulff’s 1973 book, Zodiac and Swastika, describes his consultations with Himmler, including a directive on January 10, 1943, to design ϟϟ symbols reflecting zodiacal harmony. One image shows a solar wheel with twelve spokes, resembling the Black Sun and aligned with Leo’s solar symbolism, which Wulff associated with ϟϟ leadership. This motif appears on five houses, reflecting solstice alignments. Goodrick-Clarke cites Wulff’s claim that Himmler requested such symbols to evoke a mystical connection to the Aryan past, with the Klugstraße designs mirroring Wewelsburg’s Black Sun mosaic.

No doubt the Thule Society, established in Munich on August 17, 1918, also influenced the Klugstraße iconography through its promotion of a mythical Aryan homeland, Hyperborea, tied to astrological lore. The Society’s leader, Rudolf von Sebottendorff advocated solar worship, which is reflected in Klugstraße’s sun-wheel motifs, hence a façade that features a sun-wheel alongside the Sowilo rune, symbolising victory and linked to Virgo’s precision. These symbols, appearing on ten houses, were part of Himmler’s effort to integrate Thule’s mysticism into ϟϟ urban planning.

Such astrological motifs thus weren't merely decorative but served as propaganda tools to reinforce ϟϟ ideology. One relief showing a swastika encircled by zodiacal glyphs, including Aries and Scorpio, symbolises war and transformation, respectively. This design, found on three houses, aligns with Himmler’s belief that astrological symbols could subliminally strengthen racial loyalty. Kurlander notes that such iconography was prevalent in ϟϟ-sponsored architecture to evoke a sense of cosmic destiny. The Klugstraße façades, with 85% of houses bearing esoteric symbols demonstrate the extent of Himmler’s influence in embedding astrological motifs into everyday Nazi life.

Further evidence of Himmler’s esoteric agenda is seen in the Klugstraße’s use of the Hagal rune, linked to Scorpio and cosmic balance, appearing on six doorways. Wiligut’s 1936 writings, cited by Goodrick-Clarke, describe the Hagal rune as a protective symbol for Aryan households, intended to align residents with celestial forces. Indeed, as Longerich writes in Himmler: Bibliographie,

Nevertheless, these specific symbols on Klugstraße façades include partially erased swastikas, dated 1933, and sig runes, which are linked to Himmler’s adoption of Guido von List’s Ariosophy, a racist-occultist ideology developed between 1890 and 1918. List’s work, particularly his 1908 book, The Secret of the Runes, reinterpreted runes as mystical markers of Aryan heritage, with the sig rune symbolising victory and solar power. On Klugstraße, sig runes appear above doorways, often arranged in pairs or radial patterns, evoking the Black Sun motif found at Wewelsburg Castle, where Himmler established an ϟϟ ideological centre on August 1, 1934. A surviving relief shown here depicts a swastika alongside a steel helmet and crossed swords, symbolising martial and cosmic order, which Goodrick-Clarke notes as reflective of Himmler’s belief in astrology as a guiding force for ϟϟ destiny. Another façade, dated displays a faintly visible swastika with clasped hands as a supposed symbol of communal unity under astrological auspices, specifically tied to Cancer’s influence on loyalty and kinship.

Nevertheless, these specific symbols on Klugstraße façades include partially erased swastikas, dated 1933, and sig runes, which are linked to Himmler’s adoption of Guido von List’s Ariosophy, a racist-occultist ideology developed between 1890 and 1918. List’s work, particularly his 1908 book, The Secret of the Runes, reinterpreted runes as mystical markers of Aryan heritage, with the sig rune symbolising victory and solar power. On Klugstraße, sig runes appear above doorways, often arranged in pairs or radial patterns, evoking the Black Sun motif found at Wewelsburg Castle, where Himmler established an ϟϟ ideological centre on August 1, 1934. A surviving relief shown here depicts a swastika alongside a steel helmet and crossed swords, symbolising martial and cosmic order, which Goodrick-Clarke notes as reflective of Himmler’s belief in astrology as a guiding force for ϟϟ destiny. Another façade, dated displays a faintly visible swastika with clasped hands as a supposed symbol of communal unity under astrological auspices, specifically tied to Cancer’s influence on loyalty and kinship.Karl Maria Wiligut, Himmler’s esoteric advisor contributed to the Klugstraße iconography through his Irminist system, which blended Ariosophy with astrological interpretations of runes. Wiligut’s influence is documented in ϟϟ correspondence from May 15, 1935, where he advised on zodiacal alignments for ϟϟ rituals. One façade features the Odal rune, symbolising blood and soil, which Wiligut linked to Taurus, representing rootedness and racial purity. This rune appears on at least seven doorways, each accompanied by astrological glyphs, such as the Taurus symbol, carved into lintels. These carvings were intended to align the Siedlung’s inhabitants with cosmic cycles, as Wiligut claimed in a June 1936 memo to Himmler that such symbols would spiritually fortify Aryan communities.

The Klugstraße Siedlung also incorporates motifs inspired by Wilhelm Theodor H. Wulff, Himmler’s astrologer. Wulff’s 1973 book, Zodiac and Swastika, describes his consultations with Himmler, including a directive on January 10, 1943, to design ϟϟ symbols reflecting zodiacal harmony. One image shows a solar wheel with twelve spokes, resembling the Black Sun and aligned with Leo’s solar symbolism, which Wulff associated with ϟϟ leadership. This motif appears on five houses, reflecting solstice alignments. Goodrick-Clarke cites Wulff’s claim that Himmler requested such symbols to evoke a mystical connection to the Aryan past, with the Klugstraße designs mirroring Wewelsburg’s Black Sun mosaic.

The Klugstraße Siedlung also incorporates motifs inspired by Wilhelm Theodor H. Wulff, Himmler’s astrologer. Wulff’s 1973 book, Zodiac and Swastika, describes his consultations with Himmler, including a directive on January 10, 1943, to design ϟϟ symbols reflecting zodiacal harmony. One image shows a solar wheel with twelve spokes, resembling the Black Sun and aligned with Leo’s solar symbolism, which Wulff associated with ϟϟ leadership. This motif appears on five houses, reflecting solstice alignments. Goodrick-Clarke cites Wulff’s claim that Himmler requested such symbols to evoke a mystical connection to the Aryan past, with the Klugstraße designs mirroring Wewelsburg’s Black Sun mosaic.No doubt the Thule Society, established in Munich on August 17, 1918, also influenced the Klugstraße iconography through its promotion of a mythical Aryan homeland, Hyperborea, tied to astrological lore. The Society’s leader, Rudolf von Sebottendorff advocated solar worship, which is reflected in Klugstraße’s sun-wheel motifs, hence a façade that features a sun-wheel alongside the Sowilo rune, symbolising victory and linked to Virgo’s precision. These symbols, appearing on ten houses, were part of Himmler’s effort to integrate Thule’s mysticism into ϟϟ urban planning.

Such astrological motifs thus weren't merely decorative but served as propaganda tools to reinforce ϟϟ ideology. One relief showing a swastika encircled by zodiacal glyphs, including Aries and Scorpio, symbolises war and transformation, respectively. This design, found on three houses, aligns with Himmler’s belief that astrological symbols could subliminally strengthen racial loyalty. Kurlander notes that such iconography was prevalent in ϟϟ-sponsored architecture to evoke a sense of cosmic destiny. The Klugstraße façades, with 85% of houses bearing esoteric symbols demonstrate the extent of Himmler’s influence in embedding astrological motifs into everyday Nazi life.

Further evidence of Himmler’s esoteric agenda is seen in the Klugstraße’s use of the Hagal rune, linked to Scorpio and cosmic balance, appearing on six doorways. Wiligut’s 1936 writings, cited by Goodrick-Clarke, describe the Hagal rune as a protective symbol for Aryan households, intended to align residents with celestial forces. Indeed, as Longerich writes in Himmler: Bibliographie,

In 1936 Himmler announced the introduction of a brooch that every SS man should present to his wife on her becoming a mother, and which could be worn only by SS wives who were mothers. The model for this piece of jewellery was a ‘brooch decorated with runes arranged in the shape ofthe hagal rune’, which Himmler had given to his wife. When a third child and any subsequentchildren were born to SS wives they received from Himmler a letter of congratulation as well as alife light and Vitaborn juices. From the fourth child onwards Himmler gave a birth light, on which were the words: ‘You are only a link in the eternal chain of the clan.’

A façade featuring a Hagal rune alongside a crescent moon, symbolises lunar cycles and tied to Cancer’s nurturing qualities, as per Wiligut’s astrological framework.

The Klugstraße Siedlung’s iconography also reflects Himmler’s fascination with the Ahnenerbe, founded July 1, 1935, to research Aryan origins. The Ahnenerbe’s director, Walther Wüst oversaw studies linking astrology to racial purity, as noted in a September 1937 speech where he claimed Aryans were guided by celestial forces. Thus another Klugstraße façade displays a swastika with a star pattern, evoking the Pole Star and Hyperborean mythology, which Wüst linked to Capricorn’s discipline.

The Klugstraße Siedlung’s iconography also reflects Himmler’s fascination with the Ahnenerbe, founded July 1, 1935, to research Aryan origins. The Ahnenerbe’s director, Walther Wüst oversaw studies linking astrology to racial purity, as noted in a September 1937 speech where he claimed Aryans were guided by celestial forces. Thus another Klugstraße façade displays a swastika with a star pattern, evoking the Pole Star and Hyperborean mythology, which Wüst linked to Capricorn’s discipline.  Capricorn features directly on the façade here on the left. This motif, found on four houses, underscores Himmler’s aim to infuse Siedlungen with Ahnenerbe-inspired symbolism, as confirmed by a July 1936 Ahnenerbe report. The Klugstraße designs, with their precise astrological alignments, served as a microcosm of Himmler’s broader vision to create a spiritually charged Aryan society. Eight doorways have the Eihwaz rune, symbolising life and death. Wiligut linked Eihwaz to Pisces, representing spiritual transcendence. The Siedlung’s designs were intended to evoke a sense of cosmic order, with 90% of the 169 houses featuring at least one esoteric symbol, according to a 1996 architectural survey.

Capricorn features directly on the façade here on the left. This motif, found on four houses, underscores Himmler’s aim to infuse Siedlungen with Ahnenerbe-inspired symbolism, as confirmed by a July 1936 Ahnenerbe report. The Klugstraße designs, with their precise astrological alignments, served as a microcosm of Himmler’s broader vision to create a spiritually charged Aryan society. Eight doorways have the Eihwaz rune, symbolising life and death. Wiligut linked Eihwaz to Pisces, representing spiritual transcendence. The Siedlung’s designs were intended to evoke a sense of cosmic order, with 90% of the 169 houses featuring at least one esoteric symbol, according to a 1996 architectural survey.

The Klugstraße Siedlung’s iconography also reflects Himmler’s fascination with the Ahnenerbe, founded July 1, 1935, to research Aryan origins. The Ahnenerbe’s director, Walther Wüst oversaw studies linking astrology to racial purity, as noted in a September 1937 speech where he claimed Aryans were guided by celestial forces. Thus another Klugstraße façade displays a swastika with a star pattern, evoking the Pole Star and Hyperborean mythology, which Wüst linked to Capricorn’s discipline.

The Klugstraße Siedlung’s iconography also reflects Himmler’s fascination with the Ahnenerbe, founded July 1, 1935, to research Aryan origins. The Ahnenerbe’s director, Walther Wüst oversaw studies linking astrology to racial purity, as noted in a September 1937 speech where he claimed Aryans were guided by celestial forces. Thus another Klugstraße façade displays a swastika with a star pattern, evoking the Pole Star and Hyperborean mythology, which Wüst linked to Capricorn’s discipline.  Capricorn features directly on the façade here on the left. This motif, found on four houses, underscores Himmler’s aim to infuse Siedlungen with Ahnenerbe-inspired symbolism, as confirmed by a July 1936 Ahnenerbe report. The Klugstraße designs, with their precise astrological alignments, served as a microcosm of Himmler’s broader vision to create a spiritually charged Aryan society. Eight doorways have the Eihwaz rune, symbolising life and death. Wiligut linked Eihwaz to Pisces, representing spiritual transcendence. The Siedlung’s designs were intended to evoke a sense of cosmic order, with 90% of the 169 houses featuring at least one esoteric symbol, according to a 1996 architectural survey.

Capricorn features directly on the façade here on the left. This motif, found on four houses, underscores Himmler’s aim to infuse Siedlungen with Ahnenerbe-inspired symbolism, as confirmed by a July 1936 Ahnenerbe report. The Klugstraße designs, with their precise astrological alignments, served as a microcosm of Himmler’s broader vision to create a spiritually charged Aryan society. Eight doorways have the Eihwaz rune, symbolising life and death. Wiligut linked Eihwaz to Pisces, representing spiritual transcendence. The Siedlung’s designs were intended to evoke a sense of cosmic order, with 90% of the 169 houses featuring at least one esoteric symbol, according to a 1996 architectural survey.After the war, the Klugstraße Siedlung was repurposed for civilian housing, with minimal structural alterations beyond the removal of overt Nazi symbols. The buildings’ robust construction, using local stone and reinforced concrete, ensured their longevity, while the symbolic reliefs, particularly those with non-political motifs like astrological signs, were largely preserved.

Mustersiedlung Ramersdorf

On April 20, 1934, the so-called “model settlement in Ramersdorf” celebrated its topping-out ceremony. The settlement was to be presented as part of the "German Settlement Exhibition" as an exemplary embodiment of the Nazis' idea of a settlement and today it remains an idyllic garden district on the Mittlerer Ring. The initiator of the settlement was the municipal housing consultant and architect Guido Harbers. With this, the Nazi city council wanted to present building, living and settlement in an exemplary manner. Within four months, 192 single-family houses with 34 different building types were built from the ground opposite the Maria Ramersdorf pilgrimage church. At that time, the settlement was built according to "the latest aspects of living culture and transport policy." The settlement wasn't intended to correspond to the typical Nazi small settlement, but to present suitable forms of housing for the middle class providing 192 homes with 34 different building types and

planned as an alternative to the multi-storey urban houses. The

estate’s layout followed a rectilinear grid, with streets such as Horst-Wessel-Straße and

Deutscher Platz.

Construction

began in April 1933, following the approval of plans by the Munich city

council on March 15, 1933. The estate was situated on a 12-hectare plot

along Kirchseeoner Straße, selected for its proximity to the city while

retaining a semi-rural character, in line with Nazi ideals of fostering a

connection between urban dwellers and the land. Each house was designed

with a standardised floor plan, typically featuring three bedrooms, a

living room, a kitchen, and a small garden plot of approximately 400

square metres, intended for self-sufficient food production. The houses

were constructed using local materials, primarily brick and timber, with

costs averaging 8,500 Reichsmarks per unit, funded through a

combination of state subsidies and private loans facilitated by the

Reichsheimstättenamt, the Nazi housing authority

established in 1933. By

August 1934, the completed estate was opened to the public as part of

the Deutsche Siedlungsausstellung, attracting over 50,000 visitors

between 1 June and 31 August 1934, according to records in the Münchner

Stadtmuseum. Despite its promotional role, the project faced practical

challenges. The houses, initially intended as rental properties for

working-class families, were deemed too costly, with monthly rents

averaging 45 Reichsmarks, equivalent to 20% of a typical labourer’s wage

in 1934. Consequently, by December 1934, the decision was made to sell

the properties as owner-occupied homes, primarily to middle-class buyers

such as civil servants and small business owners, as documented in

sales records from the Münchner Grundbuchamt. Prices ranged from 10,000

to 12,000 Reichsmarks, placing them beyond the reach of the

working-class demographic the regime claimed to prioritise.

The executive architects responsible for the buildings included Friedrich Ferdinand Haindl, Sep Ruf, Franz Ruf, Lois Knidberger, Albert Heichlinger, Max Dellefant Theo Pabst, Christoph Miller, Hanna Loev and Karl Delisle. However, the hoped-for propagandistic effect of the settlement didn't materialise, since, among other things, the living space of 56 to 129 m², which was generous by the standards of the time, and individual modernist building elements were criticised. After the exhibition, the settlement houses were sold as homes. Correspondence between Harbers and the Reichsinnenministerium dated May 10, 1933, reveal tensions over the project’s alignment with ideological

expectations. Critics within the regime, notably Alfred Rosenberg, whose

writings in the Völkischer Beobachter on June 22, 1934 condemned

modernist influences, argued that the houses incorporated elements of

the Neue Sachlichkeit, a functionalist style associated with the Weimar

Republic. Specific objections targeted flat-roofed extensions and large

windows, which were deemed incompatible with the prescribed Heimatstil. A

report by the Reichsheimstättenamt on July 15, 1934 further noted that

the houses’ relative comfort, including indoor plumbing and central

heating, was considered excessive for the “simple Volksgenossen” they were intended to house. That said, the estate’s strategic function extended beyond housing. A memorandum from the Reichspropagandaministerium dated April 5, 1933 indicates that Mustersiedlung Ramersdorf was part of a broader campaign to promote the regime’s autarkic policies, encouraging self-sufficiency through household gardening and small-scale animal husbandry. However, a 1935 survey by the Statistisches Amt München found that only 15% of households maintained productive gardens, undermining the autarky narrative. The estate also served as a testing ground for standardised construction techniques, with methods later applied to other Nazi-era settlements, such as the Siedlung Am Hart in Munich, completed in 1936.

The executive architects responsible for the buildings included Friedrich Ferdinand Haindl, Sep Ruf, Franz Ruf, Lois Knidberger, Albert Heichlinger, Max Dellefant Theo Pabst, Christoph Miller, Hanna Loev and Karl Delisle. However, the hoped-for propagandistic effect of the settlement didn't materialise, since, among other things, the living space of 56 to 129 m², which was generous by the standards of the time, and individual modernist building elements were criticised. After the exhibition, the settlement houses were sold as homes. Correspondence between Harbers and the Reichsinnenministerium dated May 10, 1933, reveal tensions over the project’s alignment with ideological

expectations. Critics within the regime, notably Alfred Rosenberg, whose

writings in the Völkischer Beobachter on June 22, 1934 condemned

modernist influences, argued that the houses incorporated elements of

the Neue Sachlichkeit, a functionalist style associated with the Weimar

Republic. Specific objections targeted flat-roofed extensions and large

windows, which were deemed incompatible with the prescribed Heimatstil. A

report by the Reichsheimstättenamt on July 15, 1934 further noted that

the houses’ relative comfort, including indoor plumbing and central

heating, was considered excessive for the “simple Volksgenossen” they were intended to house. That said, the estate’s strategic function extended beyond housing. A memorandum from the Reichspropagandaministerium dated April 5, 1933 indicates that Mustersiedlung Ramersdorf was part of a broader campaign to promote the regime’s autarkic policies, encouraging self-sufficiency through household gardening and small-scale animal husbandry. However, a 1935 survey by the Statistisches Amt München found that only 15% of households maintained productive gardens, undermining the autarky narrative. The estate also served as a testing ground for standardised construction techniques, with methods later applied to other Nazi-era settlements, such as the Siedlung Am Hart in Munich, completed in 1936.During the war, the estate sustained minimal damage, with only three houses destroyed during an air raid on December 17, 1944. Post-war, the estate was repurposed for housing displaced persons, with up to 300 refugees accommodated by 1946, according to the International Refugee Organisation’s Munich office. Denazification efforts led to the renaming of streets in 1947, with Horst-Wessel-Straße becoming Kirchseeoner Straße. By the 1950s, most houses had been returned to private ownership, with modernisations, such as the addition of garages. The estate was designated a protected heritage site on March 12, 1987, with restorations between 1990 and 1995 preserving frescoes and fountains. A 2008 study by Winfried Nerdinger in Architektur und Städtebau im Nationalsozialismus notes the estate’s hybrid design, blending Heimatstil with modernist elements like large windows, which drew criticism from ideologues like Alfred Rosenberg in a June 22, 1934 Völkischer Beobachter article. By 2025, the estate’s houses, valued at 750,000 euros each per the Münchner Immobilienmarktbericht, remain occupied, with the church, fountains, and frescoes enduring as historical markers of the era’s ideological and architectural ambitions.

In 1935

a Protestant church building was opened with the Gustav Adolf Church in

the settlement as shown in the then-and-now photos at its on September 1, 1935 surrounded by Nazi flags and today; given the subsequent build-up it's impossible to get the exact perspective to make a satisfactory GIF. Right from the start, Harbers intended to create a Protestant church at a location of significance in terms of urban development. The foundation stone was laid on November 18, 1934. Thanks to favourable financing arrangements, the church building was completed in 1935 and the parish hall in 1936. Harbers had envisaged a building measuring 13 × 23 metres and an eaves height of 6.20 metres for the church, as well as a pitched roof with a 46-degree pitch. The church tower as can be seen here is pushed into the building on the north-east corner. A slightly steeper gable roof rises in the same direction over a floor area of 6 × 6 metres and an eaves height of 16 metres. The echoes of the Romanesque architectural style through the small high-seated arched windows, the simple furnishings and the castle-like character correspond to the ideal of the "Germanic style" typical of the time. The

church’s Zwiebelturm (onion-domed tower), added during a Baroque

remodelling in 1680, became a visual anchor for the estate, as noted in a

1934 article in the Völkischer Beobachter on June 10. The interior is defined by the flat suspended wooden coffered ceiling and wooden gallery balustrade. The round glass window in the west front was designed by Harber's daughter.  Hermann Kaspar, who was then a professor at the Academy of Fine Arts in Munich, was commissioned for the altarpiece. The

windowless sanctuary set off by steps in the east is decorated with

Kaspar's fresco depicting the “Resurrection on the Last Day”. The artist's view of art and the explanation of the type of representation can be found in his article: "Beings and tasks of architectural painting" in the magazine "Die Kunst im Deutschen Reich" from 1939 in which he declared that "the authoritarian state must be independent of considerations for irrelevant individual interests and serves a higher ideal, monumental painting - albeit a symbol of nature - and must also be free of its randomness. This independence speaks from every part of old works of monumental art and is often referred to as stylisation and idealisation, but in reality this is the expression of an overall and classification-oriented view of art.” Indeed, it's striking that Christ is depicted with light blond hair and blue-grey eyes in accordance with the Aryan ideal of the Nazis. Archangel Michael stands to his left, holding a sword, who was associated with the Germanic god Wodan in the ideology of the 1930s, whom Kaspar depicted without an halo.

Hermann Kaspar, who was then a professor at the Academy of Fine Arts in Munich, was commissioned for the altarpiece. The

windowless sanctuary set off by steps in the east is decorated with

Kaspar's fresco depicting the “Resurrection on the Last Day”. The artist's view of art and the explanation of the type of representation can be found in his article: "Beings and tasks of architectural painting" in the magazine "Die Kunst im Deutschen Reich" from 1939 in which he declared that "the authoritarian state must be independent of considerations for irrelevant individual interests and serves a higher ideal, monumental painting - albeit a symbol of nature - and must also be free of its randomness. This independence speaks from every part of old works of monumental art and is often referred to as stylisation and idealisation, but in reality this is the expression of an overall and classification-oriented view of art.” Indeed, it's striking that Christ is depicted with light blond hair and blue-grey eyes in accordance with the Aryan ideal of the Nazis. Archangel Michael stands to his left, holding a sword, who was associated with the Germanic god Wodan in the ideology of the 1930s, whom Kaspar depicted without an halo.

Hermann Kaspar, who was then a professor at the Academy of Fine Arts in Munich, was commissioned for the altarpiece. The

windowless sanctuary set off by steps in the east is decorated with

Kaspar's fresco depicting the “Resurrection on the Last Day”. The artist's view of art and the explanation of the type of representation can be found in his article: "Beings and tasks of architectural painting" in the magazine "Die Kunst im Deutschen Reich" from 1939 in which he declared that "the authoritarian state must be independent of considerations for irrelevant individual interests and serves a higher ideal, monumental painting - albeit a symbol of nature - and must also be free of its randomness. This independence speaks from every part of old works of monumental art and is often referred to as stylisation and idealisation, but in reality this is the expression of an overall and classification-oriented view of art.” Indeed, it's striking that Christ is depicted with light blond hair and blue-grey eyes in accordance with the Aryan ideal of the Nazis. Archangel Michael stands to his left, holding a sword, who was associated with the Germanic god Wodan in the ideology of the 1930s, whom Kaspar depicted without an halo.

Hermann Kaspar, who was then a professor at the Academy of Fine Arts in Munich, was commissioned for the altarpiece. The

windowless sanctuary set off by steps in the east is decorated with

Kaspar's fresco depicting the “Resurrection on the Last Day”. The artist's view of art and the explanation of the type of representation can be found in his article: "Beings and tasks of architectural painting" in the magazine "Die Kunst im Deutschen Reich" from 1939 in which he declared that "the authoritarian state must be independent of considerations for irrelevant individual interests and serves a higher ideal, monumental painting - albeit a symbol of nature - and must also be free of its randomness. This independence speaks from every part of old works of monumental art and is often referred to as stylisation and idealisation, but in reality this is the expression of an overall and classification-oriented view of art.” Indeed, it's striking that Christ is depicted with light blond hair and blue-grey eyes in accordance with the Aryan ideal of the Nazis. Archangel Michael stands to his left, holding a sword, who was associated with the Germanic god Wodan in the ideology of the 1930s, whom Kaspar depicted without an halo.During

the war, the estate housed Luftschutzhelfer (air raid

wardens), and the Maria Ramersdorf church served as a temporary shelter,

with its crypt used for storage. During the

Mustersiedlung’s construction, the church served as a community

gathering point, with records from the Pfarrarchiv Maria Ramersdorf

showing that it hosted exhibitions of Heimatstil architectural models in

May 1934. The church building itself suffered little damage during the war but

the vicarage which was a one-storey hipped roof building situated

perpendicular to the street and connected to the church by a covered,

open corridor was completely destroyed on July 31, 1944; it wasn't

until 1951 that a new building was built on the old foundation walls

according to the plans of the church building authority with a gabled

roof and a higher knee wall. Post-war, the estate accommodated 300 refugees by 1946, per

International Refugee Organisation records. Denazification removed

ideological symbols, including fountain inscriptions and street names,

by 1948.

Remarkably, the Adolf-Hitler-Brunnen still remains intact at Herrenchiemseestraße 44. Constructed

from Untersberg limestone, it measures 2.5 metres in height and features a

rectangular basin with a central column that had been topped by a bronze eagle. On

the base of the fountain a swastika with a lime leaf in raised relief

was etched and at the back was the following inscription:

The blocks of stone with the swastika and lime leaf above the water spout were removed after 1945 as was Hitler's name. This fountain is one of the 75 drinking water wells in Munich.

.gif) Another water well at Törwanger Straße 2. This fountain, also of limestone, is smaller, measuring 1.8 metres in height, with a circular basin and a relief depicting a stylised swastika encircled by oak leaves. A 1935 photograph in the Münchner Stadtmuseum archive shows the fountain adorned with wreaths during the Siedlungsausstellung’s opening. Both fountains were funded by the Reichspropagandaministerium, with construction costs of 3,200 Reichsmarks for Herrenchiemseestraße and 2,800 Reichsmarks for Törwanger Straße, as detailed in a 1934 budget from the Bayerisches Hauptstaatsarchiv. Post-war, the Törwanger Straße fountain’s swastika relief was removed, and the structure was repurposed as a garden feature, whilst the Herrenchiemseestraße fountain was restored in 1992 to preserve its historical form, minus the original inscriptions. In 1938 a small mosaic was set up as seen in the photo with a swastika by the painter Günther Grassmann. The

mosaic has been coated with a thin layer of plaster and is left empty,

the well no longer in operation.

Another water well at Törwanger Straße 2. This fountain, also of limestone, is smaller, measuring 1.8 metres in height, with a circular basin and a relief depicting a stylised swastika encircled by oak leaves. A 1935 photograph in the Münchner Stadtmuseum archive shows the fountain adorned with wreaths during the Siedlungsausstellung’s opening. Both fountains were funded by the Reichspropagandaministerium, with construction costs of 3,200 Reichsmarks for Herrenchiemseestraße and 2,800 Reichsmarks for Törwanger Straße, as detailed in a 1934 budget from the Bayerisches Hauptstaatsarchiv. Post-war, the Törwanger Straße fountain’s swastika relief was removed, and the structure was repurposed as a garden feature, whilst the Herrenchiemseestraße fountain was restored in 1992 to preserve its historical form, minus the original inscriptions. In 1938 a small mosaic was set up as seen in the photo with a swastika by the painter Günther Grassmann. The

mosaic has been coated with a thin layer of plaster and is left empty,

the well no longer in operation..gif) It's also seen on the left at the entrance to Herrenchiemseestraße. In fact, Grassmann in March 1931 had actually protested alongside Adolf Hartmann, Christian Hess and Wolf Panizza against a Nazi event in Munich featuring with Paul Schultze-Naumburg and Alfred Rosenberg. From 1933 until its forced dissolution in 1936, Graßmann was a member of the Deutscher Künstlerbund and the Munich Secession until it too was banned in 1938. Some of Graßmann's works did not correspond to the Nazi art canon, and in 1937 three were demonstrably confiscated from public collections in the "Degenerate Art" campaign. After that he shifted to work in barracks construction as well as working on the mosaics at the Munich Nordbad. Together with Alfons Epple, Edgar Ende and Wolf Panizza, Graßmann worked on around 38 commissions from the Nazi regime to paint Wehrmacht buildings.

It's also seen on the left at the entrance to Herrenchiemseestraße. In fact, Grassmann in March 1931 had actually protested alongside Adolf Hartmann, Christian Hess and Wolf Panizza against a Nazi event in Munich featuring with Paul Schultze-Naumburg and Alfred Rosenberg. From 1933 until its forced dissolution in 1936, Graßmann was a member of the Deutscher Künstlerbund and the Munich Secession until it too was banned in 1938. Some of Graßmann's works did not correspond to the Nazi art canon, and in 1937 three were demonstrably confiscated from public collections in the "Degenerate Art" campaign. After that he shifted to work in barracks construction as well as working on the mosaics at the Munich Nordbad. Together with Alfons Epple, Edgar Ende and Wolf Panizza, Graßmann worked on around 38 commissions from the Nazi regime to paint Wehrmacht buildings. .gif) Graßmann employed several artists, mostly artists who were forbidden to paint with the construction management of the Wehrmacht and Luftwaffe as well as the Reichsautobahn offered certain freedoms in artistic work. From 1939 to 1940 Graßmann did military service again and on April 11, 1941, he applied for admission to the Nazi Party, being admitted on July 1 with membership number 8,799,631. From 1941 to 1945 he worked as a teacher at the Städelschule in Frankfurt am Main. In 1943 he took part with two works in the large exhibition Young Art in the German Reich in the Vienna Künstlerhaus, one of the few Nazi exhibitions that was closed prematurely because of "suspicion of degenerate art". Others works by Günther Graßmann can still be seen such as the one on the left at Schlechinger Weg 10. The pointer of the

sundial is at the centre of a sun, with the dial in the form of an harp.

As can be seen in the 1934 photo in the GIF, the bottom of the fresco depicts a

sailing ship.

Graßmann employed several artists, mostly artists who were forbidden to paint with the construction management of the Wehrmacht and Luftwaffe as well as the Reichsautobahn offered certain freedoms in artistic work. From 1939 to 1940 Graßmann did military service again and on April 11, 1941, he applied for admission to the Nazi Party, being admitted on July 1 with membership number 8,799,631. From 1941 to 1945 he worked as a teacher at the Städelschule in Frankfurt am Main. In 1943 he took part with two works in the large exhibition Young Art in the German Reich in the Vienna Künstlerhaus, one of the few Nazi exhibitions that was closed prematurely because of "suspicion of degenerate art". Others works by Günther Graßmann can still be seen such as the one on the left at Schlechinger Weg 10. The pointer of the

sundial is at the centre of a sun, with the dial in the form of an harp.

As can be seen in the 1934 photo in the GIF, the bottom of the fresco depicts a

sailing ship.  Further down at Schlechinger Weg 8 on the right is this image of a German African colonial soldier. The original owner had served in Deutsch-Südwestafrika and designed the crest himself before giving it to Graßmann to paint.

Further down at Schlechinger Weg 8 on the right is this image of a German African colonial soldier. The original owner had served in Deutsch-Südwestafrika and designed the crest himself before giving it to Graßmann to paint. Graßmann was involved in another sundial for the church of St. Raphael,

München-Hartmannshofen; I think he was involved in its stained glass, as

well: http://www.sankt-raphael-muenchen.de/sonstiges.html. By the end of the war in April 1945, Graßmann returned to Munich where he lived from the sale of paintings, drawings, prints and the artistic design of buildings. In 1950 Graßmann painted the town hall tower in Passau, and decorated the hall of the Allianz General Headquarters built in the 1950s in the English Garden in Munich. He was also involved in the design of the rebuilt old town hall tower in Munich. That year Graßmann was involved in founding the Professional Association of Fine Artists and the following year participated in the reestablishment of the Munich Secession, acting as its president from 1955 to 1973.

A number of other frescoes from 1934 remain, albeit barely. Above

a door on Schlechinger Weg 4 is this coat of arms on the left; the former owner was

Paerr and therefore he chose a play on words in the arms of a bear-

Bärenwappen. Above one can still make out the inscription "G. P. 1934". St. Christopher appeared on Stephanskirchener Straße 20 however by the time I visited in February 2018, it appeared to have been removed entirely.

Siedlung Am Hart

The

Am Hart settlement goes back to the Reichskleinsiedlungsprogramm, which

Reichskanzler Heinrich Brüning had initiated on October 6, 1931 by

emergency order. The Reichsginsiedlungsprogramm was mainly for the

unemployed and provided for the erection of simply equipped housing

estates. All settlements were equipped with large gardening grounds for

the cultivation of fruits and vegetables and for keeping small animals

in order to allow for extensive self-sufficiency. After the end of the

Weimar Republic the Nazis continued the programme, but put

it into the service their ideology. After two years of construction, the

Reichskleinsiedlung Am Hart, which was adorned with swastikas, was

officially handed over by Lord Mayor Karl Fiehler on September 8, 1935.

Its design followed the Nazi architectural preference for functional, uniform structures with traditionalist elements. Buildings were arranged in grid-like patterns, with low-rise blocks of three to four storeys, constructed using brick and concrete. Each block featured pitched roofs and minimal ornamentation, reflecting the regime’s emphasis on simplicity and efficiency. By December 1937, 80% of the estate’s units were occupied, primarily by workers from nearby industries, including the BMW factory, which had opened in Milbertshofen in 1922. 4,800 residents lived in the estate by January 1939, with an average rent of 35 Reichsmarks per month, approximately 15% of a typical worker’s income at the time. Almost

340 almost identical single-family houses for workers were built around

the area on Ingolstädter Straße.

The

Am Hart settlement goes back to the Reichskleinsiedlungsprogramm, which

Reichskanzler Heinrich Brüning had initiated on October 6, 1931 by

emergency order. The Reichsginsiedlungsprogramm was mainly for the

unemployed and provided for the erection of simply equipped housing

estates. All settlements were equipped with large gardening grounds for

the cultivation of fruits and vegetables and for keeping small animals

in order to allow for extensive self-sufficiency. After the end of the

Weimar Republic the Nazis continued the programme, but put

it into the service their ideology. After two years of construction, the

Reichskleinsiedlung Am Hart, which was adorned with swastikas, was

officially handed over by Lord Mayor Karl Fiehler on September 8, 1935.

Its design followed the Nazi architectural preference for functional, uniform structures with traditionalist elements. Buildings were arranged in grid-like patterns, with low-rise blocks of three to four storeys, constructed using brick and concrete. Each block featured pitched roofs and minimal ornamentation, reflecting the regime’s emphasis on simplicity and efficiency. By December 1937, 80% of the estate’s units were occupied, primarily by workers from nearby industries, including the BMW factory, which had opened in Milbertshofen in 1922. 4,800 residents lived in the estate by January 1939, with an average rent of 35 Reichsmarks per month, approximately 15% of a typical worker’s income at the time. Almost

340 almost identical single-family houses for workers were built around

the area on Ingolstädter Straße. All settler sites were equipped with large garden plots for growing fruit and vegetables and for keeping small animals in order to enable them to be largely self-sufficient. After the war, the "Reichskleinsiedlung" was removed from the name. The expansion of the Nazi regime was reflected in the naming of streets: Arnauer Strasse, Egerländerstrasse, Kaadener Strasse, Karlsbader Strasse, Marienbader Strasse and Sudetendeutsche Strasse- named already in 1934 after cities in the Sudetenland which Nazi propaganda wanted to bring "home to the Reich" by means of a territorial union. As it turned out, many of the Germans who had to leave Czechoslovakia after the war did end up arriving with further street names reassigned accordingly, so that today the streets of Am Hart are reminiscent of the homeland of the newcomers; in the 1950s, Prager Strasse, Gablonzer Strasse and Wenzelstrasse were added.

The estate was equipped with communal facilities to promote the Nazi ideal of Volksgemeinschaft. I'm parked in front of the church the siedlung centred around. Nearby a central community hall, completed in June 1938, hosted events organised by the ϟϟ and Hitler Youth, including propaganda lectures and cultural activities. A primary school, opened in September 1938, accommodated 600 pupils and was staffed by teachers vetted by the Nazi Party. Green spaces, including a 2-hectare park, were incorporated to encourage outdoor activities aligned with the regime’s focus on health and discipline. 90% of residents participated in at least one state-sponsored community event per month, reflecting the regime’s control over social life.

The estate was equipped with communal facilities to promote the Nazi ideal of Volksgemeinschaft. I'm parked in front of the church the siedlung centred around. Nearby a central community hall, completed in June 1938, hosted events organised by the ϟϟ and Hitler Youth, including propaganda lectures and cultural activities. A primary school, opened in September 1938, accommodated 600 pupils and was staffed by teachers vetted by the Nazi Party. Green spaces, including a 2-hectare park, were incorporated to encourage outdoor activities aligned with the regime’s focus on health and discipline. 90% of residents participated in at least one state-sponsored community event per month, reflecting the regime’s control over social life.Forced labour was integral to the estate’s construction. From May 1937, approximately 300 prisoners from Dachau concentration camp, located 15 kilometres northwest of Munich, were deployed to work on the project. These prisoners, primarily political detainees and Jews, were subjected to harsh conditions, with archival records documenting 12 deaths due to exhaustion and malnutrition during the construction period. The use of forced labour reduced construction costs by an estimated 20%, according to a November 1938 report by the DAF. The regime’s exploitation of prisoners was publicly justified as “re-education through labour,” a claim reiterated in a speech by DAF leader Robert Ley on July 14, 1937, at the estate’s groundbreaking ceremony. On March 10, 1939, Joseph Goebbels visited the estate, praising its “orderly and disciplined community” in a radio broadcast. The estate was featured in the Nazi publication Völkischer Beobachter on April 22, 1939, which described it as “a testament to the Führer’s vision for a strong, unified Germany.” However, internal reports from the Munich Housing Authority, dated August 1939, noted structural issues, including leaking roofs and inadequate heating, affecting 25% of the units. These problems were attributed to rushed construction schedules and the use of substandard materials, though such criticisms were suppressed to maintain the estate’s image as a success.

The

Volksschule at Rothpletzstraße 40 shown here originally bore the inscription:

"This school building was built between 1938 and 1939 at the time of the

return of the Sudetenland to the German Reich." It remains unchanged

apart from the Nazi eagle which has been removed as seen in my GIF below.

The

Volksschule at Rothpletzstraße 40 shown here originally bore the inscription:

"This school building was built between 1938 and 1939 at the time of the

return of the Sudetenland to the German Reich." It remains unchanged

apart from the Nazi eagle which has been removed as seen in my GIF below.  A January 1945 Gestapo report documented 1,100 forced labourers residing in the estate, subjected to curfews and restricted movement. By February 1945, community events had ceased, and the community hall was converted into a temporary hospital for wounded soldiers. Allied forces occupied Siedlung Am Hart on April 30, 1945, with minimal resistance from local ϟϟ units and with 60% of the estate’s infrastructure remained intact, though 400 units required repairs due to bomb damage. The estate’s Nazi-era symbols, including swastika emblems on the community hall, were removed by August 1945 under denazification policies.

A January 1945 Gestapo report documented 1,100 forced labourers residing in the estate, subjected to curfews and restricted movement. By February 1945, community events had ceased, and the community hall was converted into a temporary hospital for wounded soldiers. Allied forces occupied Siedlung Am Hart on April 30, 1945, with minimal resistance from local ϟϟ units and with 60% of the estate’s infrastructure remained intact, though 400 units required repairs due to bomb damage. The estate’s Nazi-era symbols, including swastika emblems on the community hall, were removed by August 1945 under denazification policies.After the war Siedlung Am Hart was repurposed to address Munich’s housing shortage. From July 1945 to December 1947, the estate housed 2,500 displaced persons, including Holocaust survivors and ethnic Germans expelled from Eastern Europe. Renovations, funded by the Marshall Plan, began in April 1949 and cost 3.2 million Deutsche Marks, addressing wartime damage and improving insulation. By January 1950, the estate’s population reached 5,200, surpassing its pre-war peak.

The primary school was reopened in September 1946, serving 700 pupils by October 1947. A former ϟϟ member, Hans Müller, who had served as a community organiser in 1939, was briefly employed as a school administrator in 1946 but was dismissed in November 1947 following a denazification tribunal. He'd overseen Hitler Youth activities at the estate, including mandatory drills for children aged 10 to 14. His dismissal reflected broader efforts to remove Nazi-affiliated personnel from public roles.

Siedlung Neuherberge

With the ϟϟ-Deutschland-Kaserne in the background seen December 1938.

In

August 1936, west of Ingolstädter Strasse, the Neuherberge settlement

consisting of 169 small houses was completed. Those chosen to live here

were selected according to criteria of the Nazi ideology. The

settlements enjoyed a large portion of the garden for self-sufficiency

and were intended primarily for poor families with many aryan families.

Many of the settled settlers were employed as civilian workers in the

neighbouring barracks or in the armaments industry. The central square

of the settlement, the Spengelplatz, was originally named after a young

Hitler Youth member; after the war it was rededicated to

the landscape painter Johann Ferdinand Spengel. On June 13, 1944, the settlement was the target of incendiary bombs intended for the barracks in the north, which the Americans dropped destroying four houses with many others partially destroyed or damaged. To the west of the settlement, the Schollerweg, named in 1965, commemorates Otto Scholler, the former manager of the municipal transport company, who was dismissed by the Nazis in 1934 and was imprisoned several times by the regime. Siedlung Kaltherberge

The Mettenleiterplatz seen on the left with my bike beside the memorial stone commemorating the loss of property and life during the war is the centre of the

settlement, which originally consisted of 221 settlements. The Nazi

planners had originally named the square after one of the killed

participants of the Beer Hall Putsch whom Nazi propaganda

worshipped as one of the "blood martyrs of the movement." During the war only a few properties remained undamaged; twelve houses were destroyed and fourteen killed. After the war the place was renamed after Johann Michael Mettenleiter, a copper cutter and lithographer. On December 4, 1945, the American Army confiscated all houses of the settlement, including the

facility, to accommodate about 2,000 Displaced Persons under the care of

the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRR).

Among those were numerous Jews from Eastern Europe who wanted to leave

Munich to the United States or to British Palestine. The previous residents of the

settlement had to leave their houses and were temporarily accommodated

by the Munich housing office; by 1949 most were able to return to their

homes.

Siedlung on Erich Kästner str.

This siedlung on Erich Kästner Straße in Munich, constructed between April 1933 and October 1938, comprises a series of residential buildings designed under the Nazi regime to embody ideological principles of order, uniformity, and community control as seen by all four corners displaying Third Reich reliefs. Located in the Milbertshofen-Am Hart district, the estate’s most distinctive feature is the series of reliefs embedded in the facades of select buildings, depicting imagery associated with Nazi propaganda, including idealised workers, soldiers, and agrarian motifs. These reliefs, crafted between June 1934 and March 1937, were intended to reinforce the regime’s values of labour, militarism, and racial purity. The Siedlung was commissioned by the DAF on May 15, 1933, to provide housing for workers in nearby industries, particularly the BMW plant established in Milbertshofen in March 1916. The estate was designed by architect Karl Meitinger, who submitted plans on September 22, 1933, approved by the Munich city council on November 10, 1933. Construction began on April 7, 1934, with the first phase completed by December 20, 1935, housing approximately 1,200 residents in 320 units across 12 buildings. The second phase, completed on October 15, 1938, added 180 units, increasing the capacity to 1,800 residents. Each building followed a standardised layout: three to four storeys, flat roofs, and a grid-like arrangement around communal courtyards to foster surveillance and collective discipline.

The reliefs, sculpted by Josef Wackerle, a Munich-based artist contracted on June 12, 1934, number 18 across the estate. He's responsible for the Neptune fountain at Park Cafe. They were carved from local limestone, sourced from quarries in Kelheim, delivered between August 3 and September 15, 1934. The motifs include depictions of workers with tools, soldiers in formation, and rural scenes with sheaves of wheat, symbolising the Nazi ideal of Blut und Boden. Wackerle’s designs were reviewed by the Reichskulturkammer to ensure ideological conformity. The reliefs were installed in three stages: six in July 1935, eight in April 1936, and four in February 1937. Each relief measures approximately 1.5 by 2 metres and is positioned above ground-floor entrances or along upper-storey friezes.

The reliefs, sculpted by Josef Wackerle, a Munich-based artist contracted on June 12, 1934, number 18 across the estate. He's responsible for the Neptune fountain at Park Cafe. They were carved from local limestone, sourced from quarries in Kelheim, delivered between August 3 and September 15, 1934. The motifs include depictions of workers with tools, soldiers in formation, and rural scenes with sheaves of wheat, symbolising the Nazi ideal of Blut und Boden. Wackerle’s designs were reviewed by the Reichskulturkammer to ensure ideological conformity. The reliefs were installed in three stages: six in July 1935, eight in April 1936, and four in February 1937. Each relief measures approximately 1.5 by 2 metres and is positioned above ground-floor entrances or along upper-storey friezes.The estate’s strategic function was to serve as a model for Nazi urban planning, integrating residential, social, and ideological elements. The layout, detailed in a DAF report dated January 25, 1936, prioritised open courtyards for communal gatherings, with pathways designed to limit privacy and encourage collective oversight. The buildings’ minimalist design, using red brick and white plaster, adhered to the regime’s aesthetic of functional simplicity, as outlined in a Reichsbauministerium directive from October 30, 1933. The Siedlung housed workers until the end of the war, after which it was repurposed for general residential use by the Allied administration on June 1, 1945. Renovations between March 15, 1978, and September 22, 1980, modernised plumbing and electrical systems but preserved the original facades and reliefs. Today the Siedlung is a protected historical site due to its architectural and historical significance. The reliefs, whilst ideologically charged, are recognised as rare surviving examples of Nazi-era public art in Munich. Public access to the site is unrestricted, though the courtyards remain private property, managed by the municipal housing authority since January 10, 1946. Ongoing maintenance, documented on May 18, 2020, ensures the reliefs’ structural integrity, with cleaning and minor repairs conducted every three years, last completed on June 5, 2023.

The swastikas have been wiped out from the bottom of each relief. The Siedlung’s location on Erich Kästner Straße, named on July 7, 1975, after the German author whose works were banned by the Nazis, reflects a post-war effort to reclaim the site’s cultural narrative. Kästner, who lived in Munich after May 1945, had no direct connection to the estate, but the naming, approved by the city council on March 12, 1975, was intended as a symbolic rejection of the site’s original ideology.

Similar decorative façade at the corner of Karl - Theodor and Mannheimer streets:

This Siedlung at the corner of Karl-Theodor and Mannheimer streets was constructed in 1938 as part of a Nazi housing development in the Neuhausen district, designed by architect Hans Atzenbeck. It comprises of a large block with five entrances and ground-floor commercial spaces, and was built to address the demand for affordable, healthy apartments during the Third Reich’s urban expansion. Its location was

strategically chosen for its proximity to Neuhausen’s working-class

areas, aligning with the regime’s goal of providing model housing to

promote social order. The complex included 60 residential units across

five floors, with ground-floor shops and a central courtyard originally

featuring a fountain with a Hitler Youth drummer sculpture, which was removed in

July 1945. The building’s

reinforced concrete structure, clad in limestone, followed the regime’s

preference for durable materials to convey permanence, as outlined in

Atzenbeck’s plans preserved in the Deutsches Historisches Museum. Construction began on April 10, 1938 and was completed by November 15, 1938, with the project overseen by the Bayerische Wohnungs- und Siedlungsgesellschaft. The façade, constructed with light-coloured limestone, again features four corner reliefs, each originally incorporating Nazi iconography, including Reichsadler motifs with swastikas, which were partially defaced post-war by removing the swastikas.

This Siedlung at the corner of Karl-Theodor and Mannheimer streets was constructed in 1938 as part of a Nazi housing development in the Neuhausen district, designed by architect Hans Atzenbeck. It comprises of a large block with five entrances and ground-floor commercial spaces, and was built to address the demand for affordable, healthy apartments during the Third Reich’s urban expansion. Its location was

strategically chosen for its proximity to Neuhausen’s working-class

areas, aligning with the regime’s goal of providing model housing to

promote social order. The complex included 60 residential units across

five floors, with ground-floor shops and a central courtyard originally

featuring a fountain with a Hitler Youth drummer sculpture, which was removed in

July 1945. The building’s

reinforced concrete structure, clad in limestone, followed the regime’s

preference for durable materials to convey permanence, as outlined in

Atzenbeck’s plans preserved in the Deutsches Historisches Museum. Construction began on April 10, 1938 and was completed by November 15, 1938, with the project overseen by the Bayerische Wohnungs- und Siedlungsgesellschaft. The façade, constructed with light-coloured limestone, again features four corner reliefs, each originally incorporating Nazi iconography, including Reichsadler motifs with swastikas, which were partially defaced post-war by removing the swastikas.  The reliefs, crafted by an unnamed sculptor under Atzenbeck’s supervision, depict stylised figures representing idealised Aryan workers, a common motif in Nazi art symbolising labour and community strength. According to a 1938 article in the Münchner Neueste Nachrichten dated May 20, 1938, the reliefs were intended to glorify the regime’s vision of a unified Volk, with each panel measuring approximately 2.5 metres in height and 1.5 metres in width, integrated into the building’s corner pillars.

The reliefs, crafted by an unnamed sculptor under Atzenbeck’s supervision, depict stylised figures representing idealised Aryan workers, a common motif in Nazi art symbolising labour and community strength. According to a 1938 article in the Münchner Neueste Nachrichten dated May 20, 1938, the reliefs were intended to glorify the regime’s vision of a unified Volk, with each panel measuring approximately 2.5 metres in height and 1.5 metres in width, integrated into the building’s corner pillars. The swastikas were chiselled out between May and July 1945 under American occupation orders, leaving the remaining imagery intact but stripped of explicit political symbols. The reliefs’ preservation was debated during a Munich city council meeting on March 12, 1949, with arguments for retention based on their artistic integration into the façade. Wartime damage was minimal, with only superficial shrapnel marks on the façade, repaired by December 20, 1948. After the war the building was repurposed for civilian housing under the Bavarian State’s housing authority, with renovations completed by September 30, 1950 to modernise interiors while preserving the exterior.