Continued from Remaining Nazi Structures in Westphalia (1)

Wewelsburg (North Rhine-Westphalia)

Düsseldorf's market square during an induction ceremony for 10-14 year old boys into

the “Deutsche Jungvolk“ of the Hitler-Jugend in either April 1937 or

1939. After the Nazi takeover of power, the first

book burning involving "unwanted literature" by the Deutsche

Studentenschaft, including books by Heinrich Heines, took place in

Düsseldorf on April 11, 1933. The NSDAP Gauleiter Friedrich Karl Florian

supported the mass-bearing remembrance of Albert Leo Schlageter at the

Schlagter National Monument, which had already been built in 1931, as

well as the personnel restructuring of city administration and

authorities. Hans Langels (Centre Party), who had previously been hired,

was dismissed and replaced by the ϟϟ Group leader Fritz Weitzel

(mentioned below). Many regime adversaries were arrested, abused, or

killed. Dusseldorf,

Düsseldorf's market square during an induction ceremony for 10-14 year old boys into

the “Deutsche Jungvolk“ of the Hitler-Jugend in either April 1937 or

1939. After the Nazi takeover of power, the first

book burning involving "unwanted literature" by the Deutsche

Studentenschaft, including books by Heinrich Heines, took place in

Düsseldorf on April 11, 1933. The NSDAP Gauleiter Friedrich Karl Florian

supported the mass-bearing remembrance of Albert Leo Schlageter at the

Schlagter National Monument, which had already been built in 1931, as

well as the personnel restructuring of city administration and

authorities. Hans Langels (Centre Party), who had previously been hired,

was dismissed and replaced by the ϟϟ Group leader Fritz Weitzel

(mentioned below). Many regime adversaries were arrested, abused, or

killed. Dusseldorf,

the

senior ϟϟ and police officer West (from 1938), the inspector of the

security police and the SD, the ϟϟ upper section of West, was the seat

of numerous Nazi organisations and security police institutions. The SD-Oberabschnitt West, the SA-Gruppe Niederrhein, the 20th ϟϟ-Stand,

an HJ-Bann (No. 39, Obergebiet West, Ruhr Ruhr region), from 1936 an

army headquarters administration and a Wehrmzirkkommando of the

Wehrmacht. Among the cultural-political "climaxes" were the propaganda

campaigns involving the Reichsausstellung Schaffende Volk (1937) and

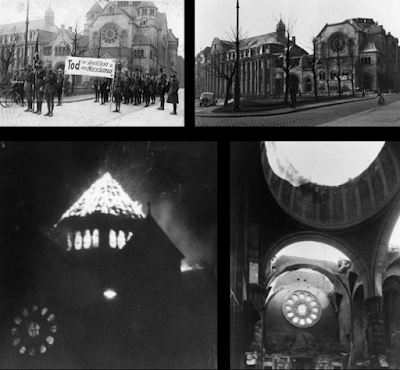

Entartete Musik (1938). On November 10, 1938, during the Pogrom Night,

the synagogues were burnt down on the Kasernenstrasse and Benrath, the

Jewish population of the city was persecuted, and at least eighteen

persons were murdered. The "Judenreferat" was responsible for the

deportation of nearly 6,000 Jews from the entire government district to

the Düsseldorf State Police Office. On October 27, 1941, the first train

drove to the concentration camps in occupied Poland (see Jewish Life in

Dusseldorf) with a total of 1003 Dusseldorf and Lower Rhine Jews from

the Derendorf freight station. More than 2200 Dusseldorfer Jews were

murdered. In 1944 about 35,000 foreign civilian workers, several

thousand prisoners of war, and concentration camp prisoners were forced

to work in the roughly 400 camps in Düsseldorf.

The Reichsausstellung Schaffendes Volk (The

Reich's Exhibition of a Productive People) of 1937 was held in the

North Park district of Düsseldorf along one mile of the Rhine

shoreline. It was opened on May 8, 1937 by Hermann Göring. Through

October of the same year it attracted more than six million visitors.

Planned in secret and deliberately designed as a rival to the 1937

International Exposition of Modern Life in Paris, the exhibition was

meant to showcase the domestic accomplishments of the National

Socialists in new housing, art, and science during their four years in

power. The fair's director was Dr. Ernst Poensgen. The exhibition was

laid out in four main divisions: industry and economics, land

utilisation and city planning, material progress (with an emphasis on

progress in synthetics), and arts and culture.

The two huge horses and horsemen sculpted out of granite for the Reichsaustellung Schaffendes Volk. Due to wrangles the exhibition, opened in the presence of Goering, ran with these monumental statues in an unfinished state - the right hand one extremely so. It was only in 1940 that the sculptor, Edwin Scharff, was allowed to complete the project, having suffered a ban at the hands of the regime in the meantime.

The ban came in 1937 when photos of these sculptures, die Rossebändiger, were presented at the exhibition "Entartete Kunst" in Munich. The argument was that the antique motif of the Rossebändiger - symbol for the rule of the human spirit over the wild nature - had not been implemented appropriately. The sculptures did not express the clear supremacy of man over the horses as the Nazis had intended. As one councillor wrote to Lord Mayor Liederley,"[i]n the midst of the rubbish, the filth, are two photographs of the horse standing pictures placed before the exhibition entrance. For this purpose, one reads that in 1937 the city of Düsseldorf paid Mk 120,000 to the sculptor Edwin Scharff." Whilst this claim was wrong, but did not change much in the unpleasant situation. It was true that the pictures were soon sent back with the diplomatic note that this must have been an "accident", but the scandal did not end there. The main point was that the two horses, which were easily held by the two "horse-riders", did not make a particularly subdued impression. However, the ancient motif, a symbol of the domination of the human mind over the wild nature, demanded, especially in the interpretation of Nazi ideology, the taming of the wild beast by man. Scharff's Rossehalter, on the contrary, expressed neither superiority over the horses, nor allowed the interpretation of the "ancient comradeship between man and horse." The two sculptures depicted carefully-looking, temperamental horses, standing on the right and left in front of the gate, a kind of gate through which the visitor had to go to get to the exhibition grounds. The horse-holders, who, in spite of their muscular nakedness, lacked the heroic Nordic idealisation of other horse-holders, seemed to have fused with the powerful flanks of the animals. The youths did not dominate either the animals or the motif, and even their small size gave no reason to hope that they could be up to the animals. Due to their immense size, which made it difficult to dismantle, the "sculptures created for eternity" based on Hitler's motto: "The greatness of the present will be measured once in the eternity which it leaves behind", remained a very visible landmark at their location. Even Hitler had to pass through the portraits of the great animals, which covered the view of the horse-holders, to get to the exhibition grounds.

The fountains here were the centre piece of the exhibition. This was the so-called Wasserachse, which was the centrepiece of the Gardenschau. In the background, the former Ehrenhalle der Partei which contained the administrative offices for the Reich Exhibition, ticket booths and a restaurant.

In June 1933, the ϟϟ-group leader Fritz Weitzel was appointed to President-Polizeiprä. Weitzel had became a member of the Nazi Party in 1925, joining the ϟϟ the following year at the age of 22, and was only 29 years old when he was police chief although he was considered in Nazi circles as incompetent. In 1930 he was promoted leader of the ϟϟ in the Rheinland and Ruhr. He became Polizeipräsident in Düsseldorf in 1933, and Höherer ϟϟ- und Polizeiführer West in 1938. During 1939 Weitzel wrote the book Celebrations of the ϟϟ Family which described the holidays to be celebrated and how married ϟϟ men and their families should celebrate them. This book, written by Weitzel, described how the Julleuchter, a Yuletide gift by Himmler to the ϟϟ, should be used. After the Germans invaded Norway on April 9, 1940 Weitzel was sent to Norway on April 21 to become Höherer ϟϟ- und Polizeiführer in the country's capital, Oslo. However, he was killed two months later by shrapnel in an aerial attack on his home town, Düsseldorf, during a visit on 19 June 1940. He is buried in the cemetery at Düsseldorf.

On September 30, 1938, the "quasi-expropriation" of the Jewish

community in Mülheim occurred. With a council decision, the synagogue at

Viktoriaplatz was forcibly sold for only 56,000 Reichsmarks to the

Stadtsparkasse. A few weeks later during Kristallnacht on 10 November,

the Jewish house of worship burned down. The Mülheim fire department

acted only to prevent the fire from spreading to neighbouring structures.

During the years 1943 and 1944, the city was repeatedly the target of

British air attacks. The most severe attack took place in the night of June 22 to 23, 1943. In three closely successive waves, 242 Lancaster,

155 Halifax, 93 Stirling, 55 Wellington, and twelve Mosquito bombers

targeted the city. The main objectives were the downtown area, the

railway lines, the tube stations, the facilities of Schmitz-Scholl (a

manufacturer of Wehrmacht supplies), the Reichsbahn repair shop, and the

harbour. The attack caused 530 deaths among the urban population and

1,630 buildings (64% of the city's buildings) were damaged or destroyed.

Approximately 40,000 residents had to be evacuated afterwards.

Another aerial attack, which actually was on the city of Oberhausen,

came on the night of November 1-2, 1944. Bombs fell on the Dümpten neighbourhood. There and in surrounding neighbourhoods 33 inhabitants were

killed. On December 24, 1944, the last serious attack occurred as a

result of Germany's Ardennes offensive, which received air support from

the Essen-Mülheim Airport. That airport was attacked by 338 British

bombers. A total of 74 inhabitants of the city lost their lives, of

which 50 were killed by a direct hit on the bunker on Windmühlenstraße.

Generaldirektor of the Bochumer Vereins, Walter Borbet, a key executive of the United Steel Works, with Hitler at the Werk Höntrop

on April 14, 1935 and the site today. The city of Bochum, situated in

the Ruhr area of Germany, had a complex and multi-faceted role during

the Nazi regime. Known as an industrial hub, the city became critically

involved in various aspects of the Nazi apparatus. Bochum's industrial

importance cannot be overstated in any discussion concerning its role

under Nazi rule. Located in the Ruhr valley, an area replete with coal

mines and factories, Bochum was a hub for industrial production,

particularly in steel and armaments. This made it a focal point for the

implementation of the Four-Year Plan, aimed at making Germany

self-sufficient and prepared for war. The city's factories were

retrofitted and expanded to meet the growing demand for weapons and

equipment, as Hitler’s war plans became increasingly apparent. Historian

Kershaw argues that places like Bochum were central to the Nazi war

effort, providing the material basis for military expansion. Moreover,

Bochum became a site for forced labour as the war progressed. Factories

were staffed with prisoners of war, and later, with forced labourers

from occupied territories. This grim aspect of industrial production

sheds light on the city’s complicity in the oppressive Nazi policies.

Mason contends that the exploitation of forced labour in industrial

cities like Bochum was not merely an economic necessity for the regime

but also a tool of subjugation, integrating the city into the wider

network of Nazi oppression. The economic gains derived from forced

labour also had broader ramifications, further entrenching the local

populace and elite in the web of Nazi moral compromises and

complicities. Through the combination of economic benefit and

ideological compliance, Bochum became a textbook example of the manner

in which ordinary German towns became inextricably linked to the

regime's war crimes. Mason argues that industrial cities like Bochum

offered a "double-edged sword"—on one side contributing to Germany's war

economy and on the other perpetuating a cycle of moral degradation and

ethical compromises. Therefore, the industrial dimension of Bochum’s

role under the Nazis was far more intricate than mere production

numbers; it was interwoven with both the aims and the malevolent methods

of the regime.

Generaldirektor of the Bochumer Vereins, Walter Borbet, a key executive of the United Steel Works, with Hitler at the Werk Höntrop

on April 14, 1935 and the site today. The city of Bochum, situated in

the Ruhr area of Germany, had a complex and multi-faceted role during

the Nazi regime. Known as an industrial hub, the city became critically

involved in various aspects of the Nazi apparatus. Bochum's industrial

importance cannot be overstated in any discussion concerning its role

under Nazi rule. Located in the Ruhr valley, an area replete with coal

mines and factories, Bochum was a hub for industrial production,

particularly in steel and armaments. This made it a focal point for the

implementation of the Four-Year Plan, aimed at making Germany

self-sufficient and prepared for war. The city's factories were

retrofitted and expanded to meet the growing demand for weapons and

equipment, as Hitler’s war plans became increasingly apparent. Historian

Kershaw argues that places like Bochum were central to the Nazi war

effort, providing the material basis for military expansion. Moreover,

Bochum became a site for forced labour as the war progressed. Factories

were staffed with prisoners of war, and later, with forced labourers

from occupied territories. This grim aspect of industrial production

sheds light on the city’s complicity in the oppressive Nazi policies.

Mason contends that the exploitation of forced labour in industrial

cities like Bochum was not merely an economic necessity for the regime

but also a tool of subjugation, integrating the city into the wider

network of Nazi oppression. The economic gains derived from forced

labour also had broader ramifications, further entrenching the local

populace and elite in the web of Nazi moral compromises and

complicities. Through the combination of economic benefit and

ideological compliance, Bochum became a textbook example of the manner

in which ordinary German towns became inextricably linked to the

regime's war crimes. Mason argues that industrial cities like Bochum

offered a "double-edged sword"—on one side contributing to Germany's war

economy and on the other perpetuating a cycle of moral degradation and

ethical compromises. Therefore, the industrial dimension of Bochum’s

role under the Nazis was far more intricate than mere production

numbers; it was interwoven with both the aims and the malevolent methods

of the regime.

Apart from its industrial significance, Bochum played an equally disturbing role in the oppressive measures enacted by the Nazi state. As a medium-sized city with a mixed population, Bochum became a site where various Nazi ideologies and policies, from anti-Semitic legislation to Aryanisation, were vigorously implemented. Bochum’s Jewish community faced extreme persecution, beginning with social ostracisation and progressing to confiscation of property and deportation. Numerous synagogues were destroyed during Kristallnacht, marking a grim escalation of anti-Jewish measures. Friedlander, a historian focusing on the Holocaust, elaborates on how mid-sized cities like Bochum were essential cogs in the bureaucratic machinery of the Final Solution. On November 9, 1938 during Kristallnacht, the Jewish citizens of Bochum were attacked with the synagogue set on fire and rioting against Jewish citizens. The first Jews from Bochum were deported to Nazi concentration camps and many Jewish institutions and homes were destroyed. Some 500 Jewish citizens are known by name to have been killed in the Holocaust, including nineteen who were younger than 16 years old. Joseph Klirsfeld was Bochum's rabbi at this time. He and his wife fled to Palestine. In December 1938, the Jewish elementary school teacher Else Hirsch began organising groups of children and adolescents to be sent to the Netherlands and England, sending ten groups in all. Many Jewish children and those from other

persecuted groups were taken in by Dutch families and thereby saved

from abduction or deportation and death. Additionally, the city was

involved in the more extensive persecution machinery of the Third Reich.

Political dissidents, Communists, and other "undesirables" were often

arrested and sent to concentration camps. Local law enforcement

cooperated with Gestapo agents in surveillance and policing activities,

underscoring how deeply the tentacles of Nazi repression had penetrated

into everyday life in Bochum. Friedlander contends that this integration

of local administration into state repression represents one of the

many insidious ways the Nazi regime managed to involve ordinary Germans

in its broader criminal activities. Peukert, in Die KPD im Widerstand (88)

reports that in the city of Bochum leading Communists were brutally

beaten by the SA, pummelled through the streets and left lying at a

street corner. This event led to an "atmosphere of paralysis" among the

workers.

Many Jewish children and those from other

persecuted groups were taken in by Dutch families and thereby saved

from abduction or deportation and death. Additionally, the city was

involved in the more extensive persecution machinery of the Third Reich.

Political dissidents, Communists, and other "undesirables" were often

arrested and sent to concentration camps. Local law enforcement

cooperated with Gestapo agents in surveillance and policing activities,

underscoring how deeply the tentacles of Nazi repression had penetrated

into everyday life in Bochum. Friedlander contends that this integration

of local administration into state repression represents one of the

many insidious ways the Nazi regime managed to involve ordinary Germans

in its broader criminal activities. Peukert, in Die KPD im Widerstand (88)

reports that in the city of Bochum leading Communists were brutally

beaten by the SA, pummelled through the streets and left lying at a

street corner. This event led to an "atmosphere of paralysis" among the

workers.

The

Nazi eagle over the entrance to the former air raid shelter at

Boltestraße 38, dated 1941-1942, remains, denuded of its swastika.

Because the Ruhr region was an area of high residential density and a

centre for the manufacture of weapons, it was a major target in the war.

Given its industrial and ideological importance, it was inevitably

targeted by Allied bombing campaigns. The devastation wrought by these

air raids served multiple purposes: disrupting Germany's war machinery

and demoralising the population. However, paradoxically, the wartime

experiences also led to a different kind of mobilisation in Bochum.

Despite the destruction, many in the city viewed the air raids as an

impetus for increased loyalty to the regime, as suffering was framed as

collective and noble sacrifice for the Fatherland. Tooze argues that

this 'rallying effect' of wartime hardship was not unique to Bochum but

constituted a broader trend across Nazi Germany, revealing the complex

psychological interplay between the regime and its populace. The

bombings also had a more direct impact on Bochum’s role in the war

effort. With factories damaged or destroyed, the city’s productivity

plummeted, affecting the overall German war economy. Here, the city’s

previously celebrated industrial prowess turned into a liability, as it

drew the destructive attention of the Allies. Despite its

vulnerabilities, Bochum was never entirely subdued; even in the latter

stages of the war, makeshift production continued, albeit at reduced

capacity. Overy emphasises the resilience of Nazi Germany's industrial

cities, including Bochum, as they adapted to the constraints imposed by

wartime conditions. This section has reached the 400-word limit. May I

continue with the next section of this paragraph?Women with young

children, school children and the homeless fled or were evacuated to

safer areas, leaving cities largely deserted to the arms industry, coal

mines and steel plants and those unable to leave. Bochum was first

bombed heavily in May and June 1943. On May 13, 1943, the city hall was

hit, destroying the top floor, and leaving the next two floors in

flames. On November 4, 1944, in an attack involving seven hundred

British bombers, the steel plant, Bochumer Verein, was hit. This

included one of the largest steel plants in Germany which had more than

ten thousand high-explosive and 130,000 incendiary bombs stored there,

setting off a conflagration that destroyed the surrounding

neighbourhoods.

The

Nazi eagle over the entrance to the former air raid shelter at

Boltestraße 38, dated 1941-1942, remains, denuded of its swastika.

Because the Ruhr region was an area of high residential density and a

centre for the manufacture of weapons, it was a major target in the war.

Given its industrial and ideological importance, it was inevitably

targeted by Allied bombing campaigns. The devastation wrought by these

air raids served multiple purposes: disrupting Germany's war machinery

and demoralising the population. However, paradoxically, the wartime

experiences also led to a different kind of mobilisation in Bochum.

Despite the destruction, many in the city viewed the air raids as an

impetus for increased loyalty to the regime, as suffering was framed as

collective and noble sacrifice for the Fatherland. Tooze argues that

this 'rallying effect' of wartime hardship was not unique to Bochum but

constituted a broader trend across Nazi Germany, revealing the complex

psychological interplay between the regime and its populace. The

bombings also had a more direct impact on Bochum’s role in the war

effort. With factories damaged or destroyed, the city’s productivity

plummeted, affecting the overall German war economy. Here, the city’s

previously celebrated industrial prowess turned into a liability, as it

drew the destructive attention of the Allies. Despite its

vulnerabilities, Bochum was never entirely subdued; even in the latter

stages of the war, makeshift production continued, albeit at reduced

capacity. Overy emphasises the resilience of Nazi Germany's industrial

cities, including Bochum, as they adapted to the constraints imposed by

wartime conditions. This section has reached the 400-word limit. May I

continue with the next section of this paragraph?Women with young

children, school children and the homeless fled or were evacuated to

safer areas, leaving cities largely deserted to the arms industry, coal

mines and steel plants and those unable to leave. Bochum was first

bombed heavily in May and June 1943. On May 13, 1943, the city hall was

hit, destroying the top floor, and leaving the next two floors in

flames. On November 4, 1944, in an attack involving seven hundred

British bombers, the steel plant, Bochumer Verein, was hit. This

included one of the largest steel plants in Germany which had more than

ten thousand high-explosive and 130,000 incendiary bombs stored there,

setting off a conflagration that destroyed the surrounding

neighbourhoods.

Another example of vandalism directed towards a relic of the Nazi era was this kriegerdenkmal honouring the fallen of the 4th Magdeburg Infantry Regiment No. 67 of the Great War. Based on a design by the sculptor Walter Becker and inaugurated in August 1935, it consisted of Ruhr sandstone brick, in front of which were two larger than life warriors who symbolised the imperial army and the Nazi Wehrmacht. The monument was an example of Nazi martial arts and his consecration was an attempt to prepare the population ideologically for future military conflict.

In February 1983, an unknown party sawed through the bronze figures; they have not been replaced.

Herford

This gravestone prompted controversy recently when it was apparently only now realised that it sported a swastika, a banned symbol here in Germany (despite covering numerous official state buildings here as checking out the link to hakenkreuzes will show). For everyone else, however, up to three years in gaol or a fine is the punishment stipulated by the the Penal Code. The grave itself is to the memory of Hermann Pantförder, a member of the Nazi Party since 1925 who died in a car accident on the way from Bielefeld to Herford. At his death, he led over a thousdand storm troopers and was responsible for a number of Nazi-era buildings in the area.

In the end, the matter appears to have been resolved when persons unknown took it upon themselves to partially chip the offending symbol away.

Bielefeld (North Rhine-Westphalia)

Reichsminister Dr. Robert Ley unveiling a statue produced by the Berlin sculptor Ernst Paul Hinckeldey to "Bielefelds bestem Sohn" June 14 1939.

Horst

Wessel was born in Bielefeld on September 9, 1907 here on August Bebel

Strasse (formerly Horst-Wessel-Strasse) and became the Nazis' most

famous 'martyrs' after his murder on February 23, 1930. As a teenager

Horst Wessel was a leader among the youth group of the German National

People’s Party, a conservative nationalist party. He would

often lead the group into brawls against Communists. But when the

organization began viewing him as too extreme he became more involved

with the Nazis and their Stormtroopers. Eventually

in 1926, he abandoned his studies of law at Berlin’s Friedrich Wilhelm

University to become a full-time Stormtrooper; as a leader of the SA, he

often made speeches and led marches and fights against Communists in

the streets. Whilst Berlin was a mainly Liberal and Communist city, with

his charisma Horst Wessel began winning over the support and votes of

many Berliners for the National Socialists. He was the author of the

lyrics to the song "Die Fahne hoch", usually known as Horst-Wessel-Lied,

which became the Nazi Party anthem and, de facto, Germany's co-national

anthem from 1933 to 1945. His death also resulted in his becoming the

"patron" for the Luftwaffe's 26th Destroyer Wing and the 18th ϟϟ

Volunteer Panzergrenadier Division during the war.After his murder

by the German Communist Party in 1930 he became the subject of a major

Nazi feature film (Hans Westmar, 1933), becoming the archetypal Nazi

hero; much of his legend, a major plank of Nazi mythology, began on the

pages of Der Angriff. More about this site at Bill's Bunker and a good overview about The Death, Burial and Ressurection of Horst Wessel from Berlin Wartourist.

Horst

Wessel was born in Bielefeld on September 9, 1907 here on August Bebel

Strasse (formerly Horst-Wessel-Strasse) and became the Nazis' most

famous 'martyrs' after his murder on February 23, 1930. As a teenager

Horst Wessel was a leader among the youth group of the German National

People’s Party, a conservative nationalist party. He would

often lead the group into brawls against Communists. But when the

organization began viewing him as too extreme he became more involved

with the Nazis and their Stormtroopers. Eventually

in 1926, he abandoned his studies of law at Berlin’s Friedrich Wilhelm

University to become a full-time Stormtrooper; as a leader of the SA, he

often made speeches and led marches and fights against Communists in

the streets. Whilst Berlin was a mainly Liberal and Communist city, with

his charisma Horst Wessel began winning over the support and votes of

many Berliners for the National Socialists. He was the author of the

lyrics to the song "Die Fahne hoch", usually known as Horst-Wessel-Lied,

which became the Nazi Party anthem and, de facto, Germany's co-national

anthem from 1933 to 1945. His death also resulted in his becoming the

"patron" for the Luftwaffe's 26th Destroyer Wing and the 18th ϟϟ

Volunteer Panzergrenadier Division during the war.After his murder

by the German Communist Party in 1930 he became the subject of a major

Nazi feature film (Hans Westmar, 1933), becoming the archetypal Nazi

hero; much of his legend, a major plank of Nazi mythology, began on the

pages of Der Angriff. More about this site at Bill's Bunker and a good overview about The Death, Burial and Ressurection of Horst Wessel from Berlin Wartourist.

The

swastika being raised at the rathaus on March 6, 1933. At 14.30, eight

SA men and steel helmsmen raised the black and white and red flag of the

German Reich, which had been defeated in the First World War in 1918,

and the Hakenkreuzfahne from the windows of the meeting hall of the town

council assembly. This action was well organised so that by the early

afternoon many people went to Schillerplatz in front of the town hall,

because a rumour went around saying something was going on. A short time

later three SA trains, half a train of steel helmets and members of the

German National Campaign met. They had two flags, wrapped with flags,

which were carried to the town hall. This was designed to celebrate with

this action the results of the Reichstag and Landtag elections on March

5, which the NSDAP had won as the strongest party. Whilst the Nazis

accounted for 43.9 per cent of the national vote, the SPD 18.3% and the

KPD %, here in Bielefeld the Nazis won 37.3 per cent. Compared to the

elections in November 1932 it could increase its share of votes by a

good 10 per cent. The SPD reached 34.4 percent and the KPD 10.3 percent.

Whilst the flags were being hoisted with the right arms raised,

Councilor Clara Delius of the DVP protested at the magistrate's meeting

before the twelve-person panel and left the meeting. Seven city councils

of the SPD and the Zentrum party followed. Clara Delius made no secret

of the fact that she was behind the symbolism of the old imperial flag.

If only these had been hoisted by steel guards, it would have remained.

However, after the Reichstag election Reichsminister Hermann Göring

sent a radio speech to the Prussian presidents, referring to "the

hoisting of the Hakenkreuzfahne on state and municipal service

buildings". "This intelligible national vote" should be recognised by

the police and tolerated. So it was in Bielefeld.

The

swastika being raised at the rathaus on March 6, 1933. At 14.30, eight

SA men and steel helmsmen raised the black and white and red flag of the

German Reich, which had been defeated in the First World War in 1918,

and the Hakenkreuzfahne from the windows of the meeting hall of the town

council assembly. This action was well organised so that by the early

afternoon many people went to Schillerplatz in front of the town hall,

because a rumour went around saying something was going on. A short time

later three SA trains, half a train of steel helmets and members of the

German National Campaign met. They had two flags, wrapped with flags,

which were carried to the town hall. This was designed to celebrate with

this action the results of the Reichstag and Landtag elections on March

5, which the NSDAP had won as the strongest party. Whilst the Nazis

accounted for 43.9 per cent of the national vote, the SPD 18.3% and the

KPD %, here in Bielefeld the Nazis won 37.3 per cent. Compared to the

elections in November 1932 it could increase its share of votes by a

good 10 per cent. The SPD reached 34.4 percent and the KPD 10.3 percent.

Whilst the flags were being hoisted with the right arms raised,

Councilor Clara Delius of the DVP protested at the magistrate's meeting

before the twelve-person panel and left the meeting. Seven city councils

of the SPD and the Zentrum party followed. Clara Delius made no secret

of the fact that she was behind the symbolism of the old imperial flag.

If only these had been hoisted by steel guards, it would have remained.

However, after the Reichstag election Reichsminister Hermann Göring

sent a radio speech to the Prussian presidents, referring to "the

hoisting of the Hakenkreuzfahne on state and municipal service

buildings". "This intelligible national vote" should be recognised by

the police and tolerated. So it was in Bielefeld.

On March 7, SA, Stahlhelm and Deutschnationaler Kampfring raised the

Nazi flag over the police headquarters, the Kreishaus, the main station

and the Haus der Technik. They burned a black-red-gold flag, the symbol

of democratic Germany. The same was repeated on March 9th. This time,

the already active "national associations" tried to flag the Eisenhütte,

the trade union building on Marktstraße, with black and white red and

Hakenkreuz, but came upon a "large crowd of SPD people and trade

unionists" and fled. In the early evening hours there was a large crowd

again at Schillerplatz. The latest news from the Westphalian newspaper

reported: "At about 19.20, the ϟϟ and

SA came, bringing along black-and-red, gold, and three-arrow flags,

which had been fetched from schools and other public and other

buildings. On Schillerplatz the flags were filled with gasoline and lit.

A great multitude pursued the process, and ended the demonstration with

the singing of the German and Horst-Wessel songs."

On March 7, SA, Stahlhelm and Deutschnationaler Kampfring raised the

Nazi flag over the police headquarters, the Kreishaus, the main station

and the Haus der Technik. They burned a black-red-gold flag, the symbol

of democratic Germany. The same was repeated on March 9th. This time,

the already active "national associations" tried to flag the Eisenhütte,

the trade union building on Marktstraße, with black and white red and

Hakenkreuz, but came upon a "large crowd of SPD people and trade

unionists" and fled. In the early evening hours there was a large crowd

again at Schillerplatz. The latest news from the Westphalian newspaper

reported: "At about 19.20, the ϟϟ and

SA came, bringing along black-and-red, gold, and three-arrow flags,

which had been fetched from schools and other public and other

buildings. On Schillerplatz the flags were filled with gasoline and lit.

A great multitude pursued the process, and ended the demonstration with

the singing of the German and Horst-Wessel songs."

Klosterplatz

at the start of the war when "Fall weiß" started - the attack on

Poland. At 4.45 am, the "Schleswig - Holstein" line ship opened fire on

Polish fortifications on the Westerplatte near Gdansk, accompanied by

the invasion of fictitious raids on German facilities (including the

transmitter Gliwitz), which the ϟϟ had prepared and which was the

propagandistic pretext for a German "counter-attack." Two German army

groups with more than 1.5 million soldiers advanced in a pincer movement

against the strategically unfavourably

postponed Polish army on September 17, 1939. The Soviets invaded

Eastern Poland, and on September 27, 1939, Warsaw capitulated

unconditionally Poland had no longer existed, the crimes of the armed

forces and the police units gave a foreboding of the brutal occupying

forces, which had now begun: about 3,000 Polish soldiers had been

killed, some 12,000 civilians were killed and an unknown number of

Polish Jews murdered. The German Reich had not proved itself as the

expected civilized opponent, but as an enemy with the will to destroy.

The headlines and covers of the Bielefeld newspapers presented fake news ("Poland

attacked!") as well as printing speeches by Hitler and extensive

articles on the German advance and the collapse of the Polish army.

Reports of excesses against Volksdeutsche fuelled the mood that

culminated in drastic depictions of the "Bromberg Bloody Sunday," when

the murder of some 1,000 Volksdeutsche, which was owed, not least, to

the dissolution of an orderly Polish administration and an overthrow to

German aggression.

Klosterplatz

at the start of the war when "Fall weiß" started - the attack on

Poland. At 4.45 am, the "Schleswig - Holstein" line ship opened fire on

Polish fortifications on the Westerplatte near Gdansk, accompanied by

the invasion of fictitious raids on German facilities (including the

transmitter Gliwitz), which the ϟϟ had prepared and which was the

propagandistic pretext for a German "counter-attack." Two German army

groups with more than 1.5 million soldiers advanced in a pincer movement

against the strategically unfavourably

postponed Polish army on September 17, 1939. The Soviets invaded

Eastern Poland, and on September 27, 1939, Warsaw capitulated

unconditionally Poland had no longer existed, the crimes of the armed

forces and the police units gave a foreboding of the brutal occupying

forces, which had now begun: about 3,000 Polish soldiers had been

killed, some 12,000 civilians were killed and an unknown number of

Polish Jews murdered. The German Reich had not proved itself as the

expected civilized opponent, but as an enemy with the will to destroy.

The headlines and covers of the Bielefeld newspapers presented fake news ("Poland

attacked!") as well as printing speeches by Hitler and extensive

articles on the German advance and the collapse of the Polish army.

Reports of excesses against Volksdeutsche fuelled the mood that

culminated in drastic depictions of the "Bromberg Bloody Sunday," when

the murder of some 1,000 Volksdeutsche, which was owed, not least, to

the dissolution of an orderly Polish administration and an overthrow to

German aggression.

Catholic

Münster had been largely antipathic towards the Nazis and the local

group of the NSDAP was not particularly large. The slow rise of the

Nazis began in 1931 with a variety of events, including sixteen major

events. Benefiting from external speakers, they experienced a steady

influx, in particular after the speeches by Göring and August Wilhelm

von Prussia on August 25, 1931 which caused a turning point. The Nazis

were able to improve their reputation among the population from “brown

Marxists” to a “decent” party. Propaganda further intensified in 1932

when nearly the entire party leadership paid a visit to Münster

including Goebbels, Robert Ley, Gregor Strasser and Wilhelm Frick as

well as Hitler himself for whom it would be his second and last visit to

Münster, after he had formerly been the Freikorpsführer. He spoke at a

campaign event on the election of the Reich President on April 8, 1932

to a total of about 10,000 people. Around 7,000 people listened to his

speech inside Halle Münsterland whilst another 3,000 listened from the

neighbouring Halle Kiffe.

Catholic

Münster had been largely antipathic towards the Nazis and the local

group of the NSDAP was not particularly large. The slow rise of the

Nazis began in 1931 with a variety of events, including sixteen major

events. Benefiting from external speakers, they experienced a steady

influx, in particular after the speeches by Göring and August Wilhelm

von Prussia on August 25, 1931 which caused a turning point. The Nazis

were able to improve their reputation among the population from “brown

Marxists” to a “decent” party. Propaganda further intensified in 1932

when nearly the entire party leadership paid a visit to Münster

including Goebbels, Robert Ley, Gregor Strasser and Wilhelm Frick as

well as Hitler himself for whom it would be his second and last visit to

Münster, after he had formerly been the Freikorpsführer. He spoke at a

campaign event on the election of the Reich President on April 8, 1932

to a total of about 10,000 people. Around 7,000 people listened to his

speech inside Halle Münsterland whilst another 3,000 listened from the

neighbouring Halle Kiffe.  The

year before the city council had refused to allow the Nazis to hold

events in the hall. Due to their increasing influence on politics and

the police this ban was no longer possible. The success of this

continuing propaganda was evident in the spring of 1933: in the 1933

Reichstag election , the Nazis increased their share of the vote from

16,246 (24.3%) to 26,490 (36.1%), but was still behind the Zentrum party

with 41.6%. A few days later, at the municipal election on March 12,

1933, this ratio had been reversed: the Nazi Party was now the strongest

party with 40.2% with the Zentrum at 39.7%. In the election on March 5,

the Nazis nationwide had managed 43.9%. The initial reaction to the

Nazi seizure of power in 1933 was met with significant ambivalence in

Münster. A stronghold of the Catholic Zentrum Party, the city initially

appeared somewhat resistant to National Socialist ideology. However,

this facade of resistance crumbled rapidly under the pressures of

Gleichschaltung, the process of Nazification. By 1934, key institutions

in Münster, such as the university and local government, were under Nazi

control. Bishop Clemens August Graf von Galen, an authoritative figure

in the city, initially attempted to reconcile Catholicism with Nazi

ideology but later became an outspoken critic. Kershaw identifies von

Galen's sermons against euthanasia and other Nazi practices as one of

the isolated instances of high-profile resistance within Germany, which

had a resounding effect on the Münster populace. Still, von Galen's

impact was limited in scope and did not translate into widespread active

resistance.

The

year before the city council had refused to allow the Nazis to hold

events in the hall. Due to their increasing influence on politics and

the police this ban was no longer possible. The success of this

continuing propaganda was evident in the spring of 1933: in the 1933

Reichstag election , the Nazis increased their share of the vote from

16,246 (24.3%) to 26,490 (36.1%), but was still behind the Zentrum party

with 41.6%. A few days later, at the municipal election on March 12,

1933, this ratio had been reversed: the Nazi Party was now the strongest

party with 40.2% with the Zentrum at 39.7%. In the election on March 5,

the Nazis nationwide had managed 43.9%. The initial reaction to the

Nazi seizure of power in 1933 was met with significant ambivalence in

Münster. A stronghold of the Catholic Zentrum Party, the city initially

appeared somewhat resistant to National Socialist ideology. However,

this facade of resistance crumbled rapidly under the pressures of

Gleichschaltung, the process of Nazification. By 1934, key institutions

in Münster, such as the university and local government, were under Nazi

control. Bishop Clemens August Graf von Galen, an authoritative figure

in the city, initially attempted to reconcile Catholicism with Nazi

ideology but later became an outspoken critic. Kershaw identifies von

Galen's sermons against euthanasia and other Nazi practices as one of

the isolated instances of high-profile resistance within Germany, which

had a resounding effect on the Münster populace. Still, von Galen's

impact was limited in scope and did not translate into widespread active

resistance. .gif) The

schloss after the war and today, reconstructed. The original

construction was probably started before 1200 and was expanded several

times over the centuries. The building was largely destroyed in the war.

The foundation stone for the reconstruction took place in 1950 and was

completed in 1958. Since then it has once again been considered one of

the most important secular Gothic monuments and is one of the main

attractions for tourists in Münster. A

secondary target of the Oil Campaign of the war, Münster was bombed on

October 25, 1944 by 34 diverted B-24 Liberator bombers, during a mission

to a nearby primary target, the Scholven/Buer synthetic oil plant at

Gelsenkirchen. During the war, Münster suffered significantly from

Allied bombing, being a crucial railway and industrial hub. The city

experienced severe destruction, particularly in 1943 and 1944, affecting

both its architectural heritage and its populace. The damage inflicted

by these bombings added another layer of suffering, but also offered an

avenue for the regime to fortify ideological commitment through shared

hardship. Ziemann provides an analysis of how the experience of air

raids led to complex reactions among citizens, from further alienation

to a deepening of commitment to the regime's war efforts.About 91% of

the Old City and 63% of the entire city was destroyed by Allied air

raids. The American 17th Airborne Division, employed in a standard

infantry role and not in a parachute capacity, attacked Münster with the

British 6th Guards Tank Brigade on April 2, 1945 in a ground assault

and fought its way into the contested city centre, which was cleared in

urban combat on the following day.

The

schloss after the war and today, reconstructed. The original

construction was probably started before 1200 and was expanded several

times over the centuries. The building was largely destroyed in the war.

The foundation stone for the reconstruction took place in 1950 and was

completed in 1958. Since then it has once again been considered one of

the most important secular Gothic monuments and is one of the main

attractions for tourists in Münster. A

secondary target of the Oil Campaign of the war, Münster was bombed on

October 25, 1944 by 34 diverted B-24 Liberator bombers, during a mission

to a nearby primary target, the Scholven/Buer synthetic oil plant at

Gelsenkirchen. During the war, Münster suffered significantly from

Allied bombing, being a crucial railway and industrial hub. The city

experienced severe destruction, particularly in 1943 and 1944, affecting

both its architectural heritage and its populace. The damage inflicted

by these bombings added another layer of suffering, but also offered an

avenue for the regime to fortify ideological commitment through shared

hardship. Ziemann provides an analysis of how the experience of air

raids led to complex reactions among citizens, from further alienation

to a deepening of commitment to the regime's war efforts.About 91% of

the Old City and 63% of the entire city was destroyed by Allied air

raids. The American 17th Airborne Division, employed in a standard

infantry role and not in a parachute capacity, attacked Münster with the

British 6th Guards Tank Brigade on April 2, 1945 in a ground assault

and fought its way into the contested city centre, which was cleared in

urban combat on the following day.

Wewelsburg

castle holds a significant place in the annals of the Second World War.

Its importance is primarily linked to Heinrich Himmler, the

Reichsführer-ϟϟ, who transformed the castle

into a pseudo-religious and ideological centre for the ϟϟ. The castle's

role in the ϟϟ's mystic and racial doctrines, its function as a training

centre, and its symbolic representation of the ϟϟ's future aspirations,

underscore its significance to Himmler and the ϟϟ. On the left are the

original plans of the ϟϟ-project of August 5, 1940, signed by Himmler

and architect Hermann Bartels. As a leading architect for the

reconstruction of the Wewelsburg Castle for the ϟϟ, Bartels had already

been appointed by the Reichsführer ϟϟ Heinrich Himmler in 1933. From

1934 the Wewelsburg was rented to the ϟϟ. According to Karl Hüser,

Wewelsburg is the "cult and terrorist site of the ϟϟ"

where ϟϟ ideologues assumed that a Saxon Wallburg was the first

predecessor building at the time of the defensive battles of King Henry I

around 930 against the Hungarians or 'Huns'. Himmler had been drawn to

Henry I in 1935, when Hermann Reischle, who represented him as a deputy

curator in the "Ahnenerbe", informed him

on October 24, 1935 that the city of Quedlinburg was to support the

organisation of the festivities for the thousandth anniversary of the

death of Henry I on July 2, 1936. He called this celebration

"propagandistically [...] a gift of heaven" and wrote: "By their

appropriate design, we can achieve with a great blow what otherwise

would be difficult to fight through in a propagandistic way in years.

For this very reason the decisive participation of the ϟϟ and thus our

influence on the preparation and organisation of the celebration must be

urgently advocated." Shortly thereafter, on November 6, 1935, Himmler

took over Wewelsburg and in the next month stated "that the ϟϟ with the

city of Quedlinburg should be the sole bearer of the celebrations on 2

July 1936."

Himmler

had been made aware of Wewelsburg by leading Nazis from the region, in

particular Adolf von Oeynhausen. Himmler initially planned a training

ground for ϟϟ leaders. A small staff of ϟϟ scientists was hired. From

the beginning of the war, new plans were directed to make a meeting

place for ϟϟ group leaders, especially on special occasions.In 1934

Himmler signed a 100-mark hundred-year lease with the Paderborn

district, intending to renovate and redesign the castle as a

Reichsführerschule ϟϟ after Karl Maria Wiligut advised him

based on the Westphalian legend of the "Battle at the birch tree". It

was to be enlarged to a ϟϟ-Führerschule. Besides physical training, a

uniform ideological orientation of the leading cadre of the ϟϟ was to be

realised. Courses for ϟϟ-officers in pre- and early history, mythology,

archaeology, astronomy and art were intended and, from 1939, the castle

was also furnished with miscellaneous objects of art, including

prehistoric objects, objects of past historical eras, and works of

contemporary sculptors and painters (mainly works by such artists as

Karl Diebitsch, Wolfgang Willrich, and Hans Lohbeck—that is, art

comporting with the aesthetics of National Socialism). In 1938 Himmler

ordered the return of all Death's head rings (Totenkopfringe) of dead

ϟϟ-men and officers to be stored in a chest in the castle as a symbol of

the ongoing membership of the decedent in the ϟϟ-Order. The whereabouts

of the approximately 11,500 rings is still unknown. Although academic

instructors were appointed who began a "research enterprise" there and

set up a large library, the "ϟϟ-Schule Haus Wewelsburg" never saw any

training take place. Himmler and Bartels transformed Wewelsburg into a

shielded central meeting place for ϟϟ generals which saw the castle

obtain a more defensive appearance, for which the white plaster was cut

off and the ditch was deepened. Inside Nordic-Germanic ornaments and

symbols on stairs, furniture, floors, ceilings, crockery, cutlery and

other everyday objects soon formed the picture.

Himmler's

had group leaders' coats of arms suspended as ornaments in 1937,

organised an annual group leadership involving a ritual swearing-in from

1938, and the storage of the ceremonial ϟϟ-Ehrenring ("ϟϟ Honour

Ring"), unofficially called Totenkopfring ("Death's Head Ring"). These

were not official state decorations, but rather a personal gift bestowed

by Himmler. The ring was initially presented to senior officers of the

Old Guard (of which there were fewer than 5,000). Each ring had the

recipient's name, the award date, and Himmler's signature engraved on

the interior and came with a standard letter from Himmler and citation

stating that the ring was a "reminder at all times to be willing to risk

the life of ourselves for the life of the whole".. It was to be worn

only on the left hand, on the "ring finger". If an ϟϟ member was

dismissed or retired from the service, his ring had to be returned. The

name of the recipient and the conferment date was added on the letter.

In 1938 Himmler ordered the return of all rings of dead ϟϟ-men and

officers to be stored in a chest in Wewelsburg Castle as a memorial to

symbolise the ongoing membership of the deceased in the ϟϟ-order. In

October 1944, Himmler ordered that further manufacture and awards of the

ring were to be halted and then ordered all remaining rings,

approximately 11,500, blast-sealed inside a hill near Wewelsburg. By

January 1945, 64% of the 14,500 rings made had been returned to Himmler

after the deaths of the "holders". In addition, 10% had been lost on the

battlefield and 26% were either kept by the holder or their whereabouts

were unknown. As for regular meetings of group leaders, only in June

1941 Himmler summoned a group of ϟϟ officials to explain to them the war

aims of the Russian campaign. According to local residents, American

GIs took the rings in 1945.

In the early years, the Wewelsburg received a completely new interior, partly decorated with ϟϟ ornamentation. The exterior of Wewelsburg was designed "by the removal of the plaster, deepening of the trenches and the erection of a new bridge" to appear more like a mediævel castle. In 1936-1937 and 1939-1941, two large ϟϟ administrative buildings were built on the forecourt. In the village, a villa was built for the chief architect and dwelling-houses for ϟϟ staff. From 1940 on, the plans under the influence of the architect Himmler commissioned architect Hermann Bartels assumed gigantic proportions. On the territory of the village of Wewelsburg, a new burial site was to be built in a three-circle circle with a radius of 635 metres around the old building. The inhabitants were to be resettled. In order to be able to realise the ongoing and planned construction work in the war, the ϟϟ established a concentration camp in Wewelsburg. From May 1939 onwards, the camp consisted of a detainee commando, which belonged to the Sachsenhausen main camp. From 1941, the concentration camp was linked to the main state camp at Niederrhein which operated until April 1943. The remaining prisoners were subordinated organisationally to the Buchenwald concentration camp . Of the altogether 3,900 documented prisoners from almost all the countries occupied by the Wehrmacht, 1,855 did not survive this camp. In March 1945, Himmler ordered the blasting of the Burganlage and the adjoining administrative buildings. Wewelsburg was burnt out completely, as was the guard-house; the adjacent buildings were completely destroyed. On April 2, 1945 the destroyed castle was taken by Americans.

In the early years, the Wewelsburg received a completely new interior, partly decorated with ϟϟ ornamentation. The exterior of Wewelsburg was designed "by the removal of the plaster, deepening of the trenches and the erection of a new bridge" to appear more like a mediævel castle. In 1936-1937 and 1939-1941, two large ϟϟ administrative buildings were built on the forecourt. In the village, a villa was built for the chief architect and dwelling-houses for ϟϟ staff. From 1940 on, the plans under the influence of the architect Himmler commissioned architect Hermann Bartels assumed gigantic proportions. On the territory of the village of Wewelsburg, a new burial site was to be built in a three-circle circle with a radius of 635 metres around the old building. The inhabitants were to be resettled. In order to be able to realise the ongoing and planned construction work in the war, the ϟϟ established a concentration camp in Wewelsburg. From May 1939 onwards, the camp consisted of a detainee commando, which belonged to the Sachsenhausen main camp. From 1941, the concentration camp was linked to the main state camp at Niederrhein which operated until April 1943. The remaining prisoners were subordinated organisationally to the Buchenwald concentration camp . Of the altogether 3,900 documented prisoners from almost all the countries occupied by the Wehrmacht, 1,855 did not survive this camp. In March 1945, Himmler ordered the blasting of the Burganlage and the adjoining administrative buildings. Wewelsburg was burnt out completely, as was the guard-house; the adjacent buildings were completely destroyed. On April 2, 1945 the destroyed castle was taken by Americans.

After

the war and today. Himmler's fascination with the occult and

pseudo-scientific racial theories led to the transformation of

Wewelsburg Castle into a mystical and ideological hub for the ϟϟ.

Himmler, who was deeply influenced by the works of Chamberlain and

Rosenberg, believed in the superiority of the Aryan race and the need

for its preservation. Wewelsburg Castle, in his view, was to become the

'centre of the world', a spiritual home for the ϟϟ, where the racial

purity of the Aryan race could be preserved and propagated. Historian

Longerich argues that Himmler's interest in the occult was not merely a

personal fascination but a strategic tool to foster a distinct identity

for the ϟϟ. According to Longerich, Himmler used the castle as a

platform to instil a sense of racial superiority and a shared destiny

among the ϟϟ members. The castle's North Tower, known as the

ϟϟ-Ordenburg, was the focal point of this ideological indoctrination. It

housed the 'Obergruppenführersaal' (Hall of the Supreme Group Leaders),

where twelve ϟϟ leaders would gather around a massive oak table,

engaging in rituals and discussions aimed at reinforcing their

commitment to the ϟϟ's racial and ideological doctrines.

Wewelsburg

is apparently the only triangular-shaped castle in Germany, built at

the beginning of the 17th century in the village of Wewelsburg. After 1934, it was used by the ϟϟ under Himmler and was to be expanded into the central ϟϟ-cult-site.

After 1941, plans were developed to enlarge it to be the so-called

"Centre of the World". In 1950, the castle was reopened as a museum and

youth hostel, now one of the largest in Germany. The castle today hosts

the Historical Museum of the Prince Bishopric of Paderborn and the

Wewelsburg 1933-1945 Memorial Museum.

Himmler with NSDAP-Reichsorganisationsleiter Robert Ley in 1937 and with his architect Bartels

While travelling through Westphalia during the Nazi electoral campaign of January 1933, Himmler was profoundly affected by the atmosphere of the region, with its romantic castles and the mist- (and myth-) shrouded Teutoburger Forest. After deciding to take over a castle for ϟϟ use, he returned to Westphalia in November and viewed the Wewelsburg castle, which he appropriated in August 1934 with the intention of turning it into an ideological-education college forϟϟ officers. Although at first belonging to the Race and Settlement Main Office, the Wewelsburg castle was placed under the control of Himmler's Personal Staff in February 1935.

Himmler's

plans included making it the "centre of the new world" ("Zentrum der

neuen Welt") following the "final victory" but only detailed plans and

models exist. It was to be finished within twenty years. The complex was

to be a centre of the "kind accordant" religion (artgemäße Religion)

and a representative estate for the ϟϟ-Führerkorps ( ϟϟ leader corps) If

the plans had been realised, the entire village of Wewelsburg and

adjacent villages would have disappeared. The population was to be

resettled and the valley flooded.

Düsseldorf

Hitler Youth leaving the castle in 1935

The

Obergruppenführersaal and mausoleum beneath the Obergruppenführer hall

then and now. In addition to the exhibition rooms in the historic rooms

of the former guard building, these two rooms from the ϟϟ era

have been preserved in the north tower of the Wewelsburg, which can be

visited during the opening hours of the memorial. The dark green

ornament on the marble floor of the Obergruppenfuhrersaal has in recent

years developed under the name Schwarze Sonne into a symbol of

identification among right-wing extremists and a supposed "sign of

power" among esotericists. Since 1991 it has been associated with the

esoteric neo-Nazi concept of the Black Sun, which has been discussed

since the 1950s.

The north tower then and now on the left. Richard J. Evans argues that the castle's function as a training centre was integral to Himmler's vision of the ϟϟ. According to Evans, Himmler saw the ϟϟ not

merely as a military organisation, but as a racial and ideological

vanguard. The training provided at the castle was intended to equip ϟϟ members

with the intellectual tools necessary to fulfil this role. The castle's

function as a training centre, therefore, was not merely a practical

consideration, but a crucial component of Himmler's vision of the ϟϟ's role in the Third Reich. The castle's symbolic representation of the ϟϟ's future aspirations further underscores its significance to Himmler and the ϟϟ. Himmler envisaged the castle as the future 'centre of the world', a spiritual and ideological hub from which the ϟϟ would

govern a post-war Aryan utopia. The castle's architecture and decor,

heavily influenced by Germanic mythology and the occult, were intended

to reflect this future vision. The castle's North Tower, for instance,

was designed to align with the North Star, a symbol of the ϟϟ's destined path to racial supremacy. Snyder argues that the castle's symbolic representation of the ϟϟ's future aspirations was a key element of Himmler's strategy to foster a sense of shared destiny among the ϟϟ. According to Snyder, the castle served as a tangible manifestation of the ϟϟ's future vision, a constant reminder of the ϟϟ's

destined role as the racial and ideological vanguard of the Third

Reich. The castle, therefore, was not merely a physical structure, but a

symbolic representation of the ϟϟ's future aspirations.

Inside

the vault at the very top of the roof, a swastika remains. This

"vault, built after the model of Mycenaean domed tombs was hewn into

the rock which possibly was to serve for some kind of commemoration of

the dead. The floor was lowered 4.80 metres although the room itself

remains unfinished. In

the middle of the vault a bowl with an eternal flame was probably

planned. In the middle of the floor a gas pipe is embedded and around

the

presumed place for the eternal flame at the wall twelve pedestals are

placed. Their meaning is unknown. Above the pedestals wall niches

existed. In the zenith of the vault a swastika is walled in. The

vault has special acoustics and illumination. The castle's crypt, with

its twelve pedestals, each bearing the name of an ϟϟ officer,

further exemplified the mystical aura Himmler sought to create. The

crypt was intended to serve as a sacred space for the commemoration of

fallen ϟϟ officers, reinforcing the notion of the ϟϟ as a knightly

order. Kershaw posits that these rituals were instrumental in fostering a

sense of unity and purpose among the ϟϟ, creating a bond that

transcended the traditional military hierarchy. The castle, thus, served

as a physical manifestation of Himmler's vision of the ϟϟ as a racial

elite, a new aristocracy that would lead the Aryan race to its destined

supremacy. The castle's role in the ϟϟ's racial and ideological

indoctrination was further amplified by its function as a training

centre. Himmler envisaged the castle as an 'ϟϟ school', where members of

the ϟϟ could be educated in the racial and ideological doctrines of

the ϟϟ. The castle housed a library with a vast collection of books on

Germanic mythology, racial theory, and the occult, reflecting Himmler's

belief in the importance of intellectual training in shaping the ϟϟ's

racial elite. The castle also hosted conferences and seminars on racial

theory, providing a platform for the dissemination of the ϟϟ's racial

and ideological doctrines.

Before

and after the war. In addition to serving as a repository for stolen

artefacts, Wewelsburg Castle was also the site of a concentration camp.

The camp, which was established in 1939, was used primarily as a source

of forced labour for the castle's renovation and expansion. The

prisoners, most of whom were Soviet PoWs, were subjected to brutal

conditions, with many dying from malnutrition, disease, and overwork.

Evans argues that the existence of the camp underscores the brutal

reality of the ϟϟ's racial and ideological doctrines, which were often

masked by the castle's mystical and ideological facade. The castle's

role as a site of brutality and oppression was further highlighted by

its use as a detention centre for high-ranking ϟϟ officers accused of

disloyalty or incompetence. Snyder suggests that the castle's function

as a detention centre was part of Himmler's strategy to maintain

discipline and loyalty within the ϟϟ. The threat of detention at the

castle served as a constant reminder of the consequences of disloyalty,

reinforcing Himmler's authority over the ϟϟ.

Düsseldorf's market square during an induction ceremony for 10-14 year old boys into

the “Deutsche Jungvolk“ of the Hitler-Jugend in either April 1937 or

1939. After the Nazi takeover of power, the first

book burning involving "unwanted literature" by the Deutsche

Studentenschaft, including books by Heinrich Heines, took place in

Düsseldorf on April 11, 1933. The NSDAP Gauleiter Friedrich Karl Florian

supported the mass-bearing remembrance of Albert Leo Schlageter at the

Schlagter National Monument, which had already been built in 1931, as

well as the personnel restructuring of city administration and

authorities. Hans Langels (Centre Party), who had previously been hired,

was dismissed and replaced by the ϟϟ Group leader Fritz Weitzel

(mentioned below). Many regime adversaries were arrested, abused, or

killed. Dusseldorf,

Düsseldorf's market square during an induction ceremony for 10-14 year old boys into

the “Deutsche Jungvolk“ of the Hitler-Jugend in either April 1937 or

1939. After the Nazi takeover of power, the first

book burning involving "unwanted literature" by the Deutsche

Studentenschaft, including books by Heinrich Heines, took place in

Düsseldorf on April 11, 1933. The NSDAP Gauleiter Friedrich Karl Florian

supported the mass-bearing remembrance of Albert Leo Schlageter at the

Schlagter National Monument, which had already been built in 1931, as

well as the personnel restructuring of city administration and

authorities. Hans Langels (Centre Party), who had previously been hired,

was dismissed and replaced by the ϟϟ Group leader Fritz Weitzel

(mentioned below). Many regime adversaries were arrested, abused, or

killed. Dusseldorf,  |

| The main railway station flying Nazi flags and today, unchanged. |

The two huge horses and horsemen sculpted out of granite for the Reichsaustellung Schaffendes Volk. Due to wrangles the exhibition, opened in the presence of Goering, ran with these monumental statues in an unfinished state - the right hand one extremely so. It was only in 1940 that the sculptor, Edwin Scharff, was allowed to complete the project, having suffered a ban at the hands of the regime in the meantime.

The ban came in 1937 when photos of these sculptures, die Rossebändiger, were presented at the exhibition "Entartete Kunst" in Munich. The argument was that the antique motif of the Rossebändiger - symbol for the rule of the human spirit over the wild nature - had not been implemented appropriately. The sculptures did not express the clear supremacy of man over the horses as the Nazis had intended. As one councillor wrote to Lord Mayor Liederley,"[i]n the midst of the rubbish, the filth, are two photographs of the horse standing pictures placed before the exhibition entrance. For this purpose, one reads that in 1937 the city of Düsseldorf paid Mk 120,000 to the sculptor Edwin Scharff." Whilst this claim was wrong, but did not change much in the unpleasant situation. It was true that the pictures were soon sent back with the diplomatic note that this must have been an "accident", but the scandal did not end there. The main point was that the two horses, which were easily held by the two "horse-riders", did not make a particularly subdued impression. However, the ancient motif, a symbol of the domination of the human mind over the wild nature, demanded, especially in the interpretation of Nazi ideology, the taming of the wild beast by man. Scharff's Rossehalter, on the contrary, expressed neither superiority over the horses, nor allowed the interpretation of the "ancient comradeship between man and horse." The two sculptures depicted carefully-looking, temperamental horses, standing on the right and left in front of the gate, a kind of gate through which the visitor had to go to get to the exhibition grounds. The horse-holders, who, in spite of their muscular nakedness, lacked the heroic Nordic idealisation of other horse-holders, seemed to have fused with the powerful flanks of the animals. The youths did not dominate either the animals or the motif, and even their small size gave no reason to hope that they could be up to the animals. Due to their immense size, which made it difficult to dismantle, the "sculptures created for eternity" based on Hitler's motto: "The greatness of the present will be measured once in the eternity which it leaves behind", remained a very visible landmark at their location. Even Hitler had to pass through the portraits of the great animals, which covered the view of the horse-holders, to get to the exhibition grounds.

The fountains here were the centre piece of the exhibition. This was the so-called Wasserachse, which was the centrepiece of the Gardenschau. In the background, the former Ehrenhalle der Partei which contained the administrative offices for the Reich Exhibition, ticket booths and a restaurant.

The

statues carved for the exhibition may still be seen, such as

Zimmermann's 'Bauer,' 'Bäuerin,' Hoselmann's 'Falkner' and Zschorsch's

'Winzerin' shown here. There were originally a dozen but some are

missing. Known as Die Ständischen (The Estates), representing the professions and classes of the "creative people," they

were created by Düsseldorf sculptors Hans Breker (a brother of Arno

Breker), Ernst Gottschalk, Willi Hoselmann, Robert Ittermann, Erich

Kuhn, Josef Daniel Sommer, Kurt Zimmermann, Alexander Zschokke and

Alfred Zschorsch. The

figures had actually been removed before the visit of Adolf Hitler,

which took place on October 2, 1937, due to a lack of artistic

execution.

Four of the sculptures were put up again on the water basin in 1941, and flower baskets were placed on the empty plinths. "The Fisherman" was handed over to the city in 2006 from private ownership, and "The Shepherdess" was set up in front of a children's playground in Benrath. Both came back to their old place in the Nordpark in 2006, the remaining six sculptures are considered missing. On the other hand, the sculpture "Die Sitzende" by Johannes Knubel, which is not part of the "Ständische", remained, which is still in the Nordpark.

The former Reichsmuseum für Wirtschafts- und Gesellschaftskunde (now the NRW Forum) topped with Arno Breker's 1926 Aurora, created during the exhibition. Eight decades later the American provocateur

Spencer Tunick took advantage of Aurora for his latest nude group portrait photograph in Düsseldorf when he invited over eight hundred volunteers to strip down near the nude. Tunick had openly shied away from any connections with the Nazi regime Breker served, declaring that for him at least, “bodies are about freedom and beauty.”

In the summer of 2015 the Aurora was restored on the roof from which the "goddess of the dawn" had sat continuously for ninety years. Breker, who never expressed any regret for his work on behalf of the Nazis, was classified a "fellow traveller" by an Allied de-Nazification tribunal and moved to Dusseldorf where he eventually died and is buried in the city's Nordfriedhof.

Düsseldorf's Adolf Hitler Platz with its Kugelspielerin has now reverted back to Graf-Adolf-Platz

The Nazi eagle over the entrance of police headquarters at Jürgensplatz remains, but is covered by a plaque reading "All are equal before the law." Built from 1929 to 1932, this served as headquarters for representatives of the ϟϟ Upper Section West, the 20th ϟϟ regiment, the 6th ϟϟ Rider standard and the 4th ϟϟ Lieutenant Colonel. It was at this site that 7, 101 men and 851 women were imprisoned as

opponents of the Nazis. Many prisoners were handed over to the Gestapo

for interrogation.Four of the sculptures were put up again on the water basin in 1941, and flower baskets were placed on the empty plinths. "The Fisherman" was handed over to the city in 2006 from private ownership, and "The Shepherdess" was set up in front of a children's playground in Benrath. Both came back to their old place in the Nordpark in 2006, the remaining six sculptures are considered missing. On the other hand, the sculpture "Die Sitzende" by Johannes Knubel, which is not part of the "Ständische", remained, which is still in the Nordpark.

The former Reichsmuseum für Wirtschafts- und Gesellschaftskunde (now the NRW Forum) topped with Arno Breker's 1926 Aurora, created during the exhibition. Eight decades later the American provocateur

Spencer Tunick took advantage of Aurora for his latest nude group portrait photograph in Düsseldorf when he invited over eight hundred volunteers to strip down near the nude. Tunick had openly shied away from any connections with the Nazi regime Breker served, declaring that for him at least, “bodies are about freedom and beauty.”

In the summer of 2015 the Aurora was restored on the roof from which the "goddess of the dawn" had sat continuously for ninety years. Breker, who never expressed any regret for his work on behalf of the Nazis, was classified a "fellow traveller" by an Allied de-Nazification tribunal and moved to Dusseldorf where he eventually died and is buried in the city's Nordfriedhof.

Düsseldorf's Adolf Hitler Platz with its Kugelspielerin has now reverted back to Graf-Adolf-Platz

Die Kugelspielerin, seen in the postcard above, shown here in the 1930s and today.

Hitler’s

two-and-a-half hour speech

to the Industry Club took place here at the Parkhotel on January

27, 1932, probably

the most important speech Hitler gave before becoming chancellor a year

later, helping overcome the skepticism of many in the business community

about the putative socialism of the Nazi Party. The speech,

later published

as a pamphlet, was carefully constructed to appeal to the economic and

political interests of his affluent and influential audience. Hitler

emphasised the importance of

personality, the distinction of the German nation, and the beneficence

of struggle. His

critique of democracy and praise of racial and political hierarchy

struck a responsive

chord. Study of this speech my help to understand why so many of

Germany’s conservative economic elite were prepared to accept Hitler’s

leadership

despite his record and reputation as Jew-baiting rabble-rouser.

Hitler’s

major argument was that only the Nazis could prevent the eventual

triumph of Bolshevism in Germany. Only the Nazis could provide the Weltanschauung to

overcome the debilitating class conflict Marxism had supposedly

created, the Weimar multi-party “system” had fostered, and the

depression had exacerbated. Only they could restore unity to the nation,

and the nation to

its former greatness. Only they could hold democracy and its discontents

in check.

Hitler projected an optimistic attitude of self-reliance that closely

corresponded to the entrepreneurial mindset of successful businessmen.

They would readily have agreed with

him that it was inconsistent and counterproductive to adhere to the

“leadership principle,” individual achievement and competition, and

private property in the economy,

but to favour democracy, the egalitarian principle, pacifism, and

internationalism in politics. What democracy is to politics, Hitler

warned, communism is to the economy.

The