The sources and questions relate to Case study 1: Japanese expansion in East Asia (1931–1941) – Responses: International response, including US initiatives and increasing tensions between the US and Japan.

Source I

Andrew Gordon, a US historian, writing in the book A Modern History of Japan: From Tokugawa Times to the Present (2003).

When Japan moved into northern Indochina, the US responded with a gradually expanding export embargo. This provoked some sections of the Japanese military to argue for a pre-emptive strike against the United States and its allies. Japan followed this by extending their hold over Indochina, gaining Vichy permission to occupy the entire peninsula in July 1941 [‘Vichy’ refers to the government of the French state between 1940 and 1944]. The agreement left Japan as the virtual ruler of the French colony.

The Americans countered this advance with a strong and threatening move. Roosevelt immediately pulled together an international embargo that cut off all foreign oil supplies to Japan. He also offered military supplies to China. Without oil Japan could not sustain its military or economy. It faced a difficult choice. It could agree to American conditions for lifting the embargo by retreating completely from China. Or it could take control of the Southeast Asian oil fields by force and negotiate for a ceasefire from that strengthened position.

For a time, it pursued both courses. Japanese diplomats sought in vain to negotiate a formula for a partial retreat in China that might satisfy both their own reluctant army and the United States.

The Japanese military, meanwhile, drew up plans for an attack that might force the Western powers to recognise its hegemony in Asia.

Source J

Osami Nagano, Chief of the Japanese Naval General Staff, speaking at the Imperial Conference, 6 September 1941.

Based on the assumption that a peaceful solution has not been found and war is inevitable, the Empire’s oil supply, as well as the stockpiles of many other important war materials, is being used up day by day with the result that the national defence power is gradually diminishing. If this deplorable situation is left unchecked, I believe that, after a lapse of some time, the nation’s strength will diminish.

On the other hand, the defence of military installations and key points of Britain, the United States and other countries in the Far East, as well as military preparations of these nations, particularly those of the United States, are being strengthened so quickly that by next year we will find it difficult to oppose them. Therefore, wasting time now could be disastrous for the Empire. I believe that it is imperative [essential] for the Empire that it should first make the fullest preparations and lose no time in carrying out positive operations with firm determination, in order that it can find a way out of the difficult situation.

Source K

Chihiro Hosoya, a Japanese professor of history, writing in the article “Miscalculations in Deterrent Policy: US-Japanese Relations, 1938–1941”, for the academic publication Journal of Peace Research (1968).

According to a US public opinion survey of late September [1941], the number of Americans favouring strong action against Japan had greatly increased. Furthermore, Roosevelt stated on 12 October that the United States would not be intimidated. The Tripartite Pact had worsened relations with the United States. Japanese army officers demanded an acceleration of southern expansion. Even before the Tripartite Pact, Japan had demanded permission to move troops into southern Indochina and did so on 28 July. The Japanese pressures on Indochina led the US government to freeze Japanese assets in the United States and to impose an embargo against Japan. Officers in the Japanese navy were resolved to go to war because of the oil embargo. They were anxious about the existing supply of oil turning the Japanese navy into a “paper navy” [powerless navy].

Source L

David Low, a cartoonist, depicts Japanese expansion in the cartoon “Enough in the tank to get to that filling station?” in the British newspaper The Evening Standard (8 August 1941). The sign on the side of the building is “Dutch E. [East] Indies and on the vehicle it is “Jap. [Japanese] Oil Reserves.

9. (a) What, according to Source K, were the factors contributing to tensions between Japan and the US? [3]

(b) What does Source L suggest about Japanese expansion? [2]

10. With reference to its origin, purpose and content, analyse the value

and limitations of Source K for an historian studying the tensions

between the US and Japan. [4]

11. Compare and contrast what Sources I and J reveal about the increasing tensions between the US and Japan. [6]

12. “Mutual fear led to increasing tensions between the US and Japan.”

Using the sources and your own knowledge, to what extent do you agree

with this statement? [9]

Example from former student who ended up obtaining a 7 in the course at HL (click to enlarge):

November 2017

The sources and questions relate to Case study 1: Japanese expansion in East Asia (1931–1941) — Causes of expansion: The impact of Japanese nationalism and militarism on foreign policy.

Source I

An extract from a Japanese government statement, “The Fundamental Principles of National Policy” (August 1936).

(1) Japan must strive to eradicate [eliminate] the aggressive policies of the great powers ...

(3) ... in order to promote Manchukuo’s healthy development and to stabilize Japan-Manchukuo national defense, the threat from the north, the Soviet Union, must be eliminated; in order to promote our economic development, we must prepare against Great Britain and the United States and bring about close collaboration between Japan, Manchukuo, and China. In the execution of this policy, Japan must pay due attention to friendly relations with other powers.

(4) Japan plans to promote her racial and economic development in the South Seas, especially in the outlying South Seas area. She plans to extend her strength by moderate and peaceful means without arousing other powers. In this way, concurrently with the firm establishment of Manchukuo, Japan must expect full development and strengthening of her national power.

[Source: Republished with permission of Taylor & Francis Group LLc Books, from Japan: a Documentary History, David J. Lu, 1996; permission conveyed through Copyright Clearance Center, Inc]

Source J

William Beasley, a professor of the history of the Far East, writing in the academic book Japanese Imperialism, 1894–1945 (1987).

Central to the basic propositions was the intention that Japan ... must establish cordial [friendly] relations with the peoples of the area founded on the principles of co-existence and co-prosperity. It would also undertake economic expansion on its own account by creating a strong coalition between Japan, Manchukuo and China and by extending its interests in South-East Asia in gradual and peaceful ways. There were some conditions. The army must be given forces in Korea and Kwantung [Guandong] sufficient to deal with any attack from Soviet Russia. The navy must have a fleet capable of maintaining ascendancy in the west Pacific against that of the United States.

Sino-Japanese [Chinese-Japanese] cooperation, designed to detach Nanking [Nanjing] from its communist affiliations [links], though highly desirable must not be allowed to stand in the way of treating north China as a “special region” to be brought into close relationship with Japan and Manchukuo.

It was, for example, to provide strategic materials, in order to strengthen their defences against the Soviet Union. As to the south, a gradual and peaceful approach was intended to avert fears in countries of the area concerning Japanese aims ...

From the point of view of the ministers in Tokyo, none of this was meant to bring about territorial expansion. They still thought in terms of informal empire, that is, of securing an increase in Japan’s privileges through pressure exerted on Asian governments, including that of China.

[Source: JAPANESE IMPERIALISM, 1894-1945 by Beasley (1987) p.202. By permission of Oxford University Press]

Source K

Hans van de Ven, a professor of modern Chinese history, writing in the academic book War and Nationalism in China: 1925–1945 (2003).

By 1933, Japan’s military strategy aimed at defending itself against the Soviet Union, China and the British and American navies. Massive investment programmes in the heavy, chemical, and machinery industries followed to give Japan the industrial base to sustain itself in time of war, and also of course to deal with the problems of the Depression. In 1936, Japan stepped up its military expenditures when a new cabinet accepted the build-up of national strength as Japan’s highest priority ...

Japan therefore developed a strategic doctrine aimed at defending Japan by aggressive offensive operations of limited duration, to be concluded before its major enemies could concentrate their forces in East Asia. To defeat China before such a war was part of this strategy. Worried about war with the Soviet Union and the Western powers, the “removal of China”, as the aggressive General Tojo stated in a telegram from Manchuria to Tokyo in early 1937, would eliminate “an important menace from our rear” and release forces for service on more critical fronts. If the military build-up and the political influence of the army in Japanese politics were causes for worry in China, so were the expansionist tendencies of the Kwantung [Guandong] Army in Manchuria.

[Source: From: War and Nationalism in China: 1925–1945, Hans van de Ven, 2003, Routledge, reproduced by permission of Taylor & Francis Books UK.]

Source L John Bernard Partridge, an illustrator and cartoonist, depicts Japan threatening China in an untitled cartoon for the British magazine Punch (21 July 1937). Note: The word on the tail is Manchukuo.

Chinese dragon: I say, do be careful with that sword! If you try to cut off my head I shall really have to appeal to the League again.

[Source: PUNCH Magazine Cartoon Archives www.punch.co.uk]

Example under test conditions from student [click to enlarge]:

May 2018

My comments: Here the IBO carelessly referred to Chiang Kai-Shek as 'Jiang Jieshi'

throughout without any attempt to at least offer his name as recognised

by the majority of the world. It also refers to 'GMD' instead of 'KMT',

confusing students who learn the traditional name and showing contempt

for Cantonese speakers, especially in Hong Kong and Taiwan. Its

description of the cartoon was completely incorrect which resulted in my

Chinese-speaking students to suffer.

The

sources and questions relate to case study 1: Japanese expansion in

East Asia (1931–1941) — Causes of expansion: political instability in

China.

Source I

Jonathan D Spence, an historian, writing in the academic book The Search for Modern China (1999).

The outbreak of full-scale war with Japan in 1937 ended any chance that

Jiang Jieshi might have had of creating a strong and centralised

nation-state. Within a year, the Japanese deprived the Guomindang [the

Nationalists] of all the major Chinese industrial centres and the most

fertile farmland. Jiang’s new wartime base, Chongqing, became a symbolic

centre for national resistance to the Japanese, but it was a poor place

from which to launch any kind of counterattack. Similarly, the

Communist forces were isolated in Shaanxi province, one of the poorest

areas in China, with no industrial capacity. It was not clear if the

Communists would be able to survive there, and certainly it seemed an

unpromising location from which to spread the revolution.

For the first years of the war, the dream of national unity was kept

alive by the nominal [in name only] alliance of the Nationalist and

Communist forces in a united front. Communists muted [reduced the focus

on] their land reform practices and moderated their rhetoric

[propaganda], while the Guomindang tried to undertake economic and

administrative reforms that would strengthen China in the long term. But

by early 1941 the two parties were once again engaging in armed clashes

with each other.

Source J

Chang-tai Hung, a professor of humanities, writing in the specialist

history book War and Popular Culture: Resistance in Modern China,

1937–1945 (1994).

The outbreak of full-scale war with Japan in 1937 dealt a devastating

blow to the Nationalist [Guomindang] government’s efforts to

recentralise its authority and revive the economy. It also ended Jiang

Jieshi’s chance of crushing the Communist forces, who were isolated in

the barren and sparsely populated Shaanxi province. The war displaced

the Nationalists from their traditional power base in the urban and

industrial centres, and forced them to move to the interior. At the same

time, it provided an ideal opportunity for the Communists to expand

their influence in north China and become a true contender for national

power.

For many Chinese resisters, the clash with Japan turned out to be a

unifying force. The Marco Polo Bridge became a compelling symbol of

China’s unity. Resisters looked at war as an antidote to chaos. Despite

some progress made toward economic growth and political integration by

the Nationalist government on the eve of the war, the country was still

largely fragmented. Regional militarists remained a serious threat to

the government, and the armed conflict between the Nationalists and the

Communists persisted. Political instability bred fear and fuelled great

discontent in society.

Source K

Jiang Jieshi, head of the Chinese Nationalist [Guomindang] government

between 1928 and 1949, in a speech at an Officers Training Camp (July

1934).

This speech was not published until July 1937.

Now let us look at our own condition. How do we stand? Have we fulfilled

the necessary conditions for resisting the enemy? We ourselves can

answer that question simply and sadly in one brief sentence: “We have

made no preparations whatsoever.” Not only materially are we unprepared,

not only have we not organised our resources, but we are not even

unified in thought and spirit. I make bold to say that if we were now to

be involved in a war with Japan, groups opposed to the Government would

be sure to take advantage of the situation to create trouble. This

alone would be sufficient to seal our fate. Even before the enemy’s

actual attack, internally there would be chaos. In such circumstances

how could we possibly resist the enemy? How could we revive our race and

nation? How could we ensure that our children would continue to enjoy

the glorious heritage of five thousand years? From the military point

of view we have not the qualifications at present for an independent

state; we are not fit to be called a modern nation. So naturally we

cannot resist Japan, but must suffer at her hands.

Source L

Cai Ruohong, a cartoonist and member of the Chinese League of Left-Wing

Artists, depicts a handshake between the Chinese Communist Party (left)

and the Chinese Nationalist Party (Guomindang) (right) in the cartoon “A

Sacred Handshake” (c1937). The figure in the centre of the picture is a

caricature representing Japan.

9. (a) What, according to Source J, were the challenges faced by the Nationalist [Guomindang] government of China as a result of the outbreak of war with Japan in 1937? [3]

(b) What does Source L suggest about the relations between the Chinese Communist Party and the Nationalist Party [Guomindang] in 1937? [2]

10. With reference to its origin, purpose and content, analyse the value and limitations of Source K for an historian studying political instability in China between 1931 and 1941. [4]

11. Compare and contrast what Sources I and J reveal about political instability in China up to 1941. [6]

12. Using the sources and your own knowledge, discuss the view that Japanese aggression furthered political instability in China between 1931 and 1941. [9]

November 2018

Read sources I to L and answer questions 9 to 12. The sources and questions relate to case study 1: Japanese expansion in East Asia (1931–1941) — Responses: League of Nations and the Lytton Report.

Source I

The Lytton Report (4 September 1932).

Without declaration of war, a large area of what was indisputably Chinese territory has been forcibly seized and occupied by the armed forces of Japan and has, in consequence of this operation, been separated from and declared independent of the rest of China. The steps by which this was accomplished are claimed by Japan to have been consistent with the obligations of the Covenant of the League of Nations, the Kellogg–Briand Pact and the Nine-Power Treaty of Washington, all of which were designed to prevent action of this kind ... The justification has been that all the military operations have been legitimate acts of self-defence, the right of which is implicit in all the multilateral treaties mentioned above, and was not taken away by any of the resolutions of the Council of the League. Further, the administration which has been substituted for that of China in Manchuria is justified on the grounds that its establishment was the act of the local population, who spontaneously asserted their independence, severed all connection with China and established their own government. Such a genuine independence movement, it is claimed, is not prohibited by any international treaty or by any of the resolutions of the Council of the League of Nations.

[Source: The Lytton Report (4 September 1932). Copyright United Nations Archives at Geneva.]

Source J

Chokyuro Kadono, a leading Japanese businessman and commentator, who had significant interests in Manchuria and China, writing in the article “A Businessman’s View of the Lytton Report” in the Japanese magazine Gaiko Jiho (November 1932).

As has been officially declared by the Imperial Government more than once, Japan has no territorial ambitions in Manchuria. Japan has given formal recognition to Manchuria as an independent state [Manchukuo], assuring it full opportunity for growth and organisation ... At the same time, Japan hopes thereby to rescue Manchukuo from the destruction caused by China’s internal disorders and give it opportunity to attain free development, so that it may be able to play its part in easing the world’s economic difficulty by offering a very safe and valuable market in the Far East. This aspect of Japan’s policy should have been quite clear to the Lytton Commission. But unfortunately, the Lytton Report makes an altogether inadequate estimate of Manchuria’s economic value, and entirely fails to do justice to the previously mentioned motive of Japan in recognising Manchukuo ... Japan is fully prepared, in view of the position she rightly occupies among the nations of the world, to do her best to support China in her work of unification and reconstruction to the end that peace may thereby be assured in the Far East. This aspect of Japan’s policy should have been quite clear to the Lytton Commission.

[Source: adapted from A businessman’s view of the Lytton Report, Chokiuro Kadono, published in The Herald of Asia, Tokyo October 1932; http://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1083&context=moore]

Source K

Ryōichi Tobe, a professor of the history of modern Japan, writing in the chapter “The Manchurian Incident to the Second Sino–Japanese War” in the Japan–China Joint History Research Report (2011).

The Guangdong [Kwantung] Army continued its advance into Chinese territory ... To serve as head of the new state, the Japanese took the deposed Chinese emperor Puyi out of Tianjin under cover of riots that the Japanese staged in the city and brought him to Manchuria. Japan’s position that it acted in self-defence to protect its own interests thus began to lose credibility, and the League of Nations grew increasingly suspicious. On October 24 [1931], the League Council voted for the withdrawal of Japanese troops by a specific deadline, but Japan’s opposition alone defeated the resolution. Finally, with Japan’s agreement, the League Council decided on December 10 to send a commission to the scene to investigate, and deferred any decision until the investigation was completed ... the [resulting] Lytton Report refused to recognise the Guangdong Army’s actions following the Manchurian Incident as legitimate self-defence, nor did it accept the claim that Manchukuo had been born from a spontaneous independence movement.

[Source: adapted from Japan-China Joint History Research Report March 2011: The Manchurian Incident to the Second Sino-Japanese War, by Tobe Ryōichi. Ministry of Foreign Affairs Japan, http://www.mofa.go.jp/region/asia-paci/china/pdfs/jcjhrr_mch_en1.pdf.]

Source L

Bernard Partridge, a cartoonist, depicts the response of the League of Nations to the Manchurian crisis in the cartoon “The Command Courteous” for the British magazine Punch (12 October 1932). The wording on the woman’s cap is “League of Nations”, on the newspaper, “Lytton Report”, on the dog, “Japan” and the bone, “Manchuria”. The caption is “League of Nations, ‘Good dog—drop it!’”.

The sources and questions relate to case study 1: Japanese expansion in East Asia (1931–1941) — Responses: League of Nations and the Lytton Report.

9. (a) What, according to Source J, was Japan’s attitude toward Manchuria/Manchukuo and China? [3]

(b) What does Source L suggest about the position of Japan and the League of Nations regarding the Manchurian crisis? [2]

10. With reference to its origin, purpose and content, analyse the value and limitations of Source J for an historian studying Japan’s response to the Lytton Report in the early 1930s. [4]

11. Compare and contrast what Sources I and K reveal about Japanese actions in China. [6]

12. Using the sources and your own knowledge, discuss the view that the ineffectual response of the League of Nations was the main factor in encouraging Japanese expansion in China. [9]

Student Example (click to enlarge):

Another example:

May 2019

Read sources I to L and answer questions 9 to 12. The sources and questions relate to case study 2: German and Italian expansion (1933–1940) — Responses: international response to German aggression (1933–1938).

Source I

Notes for the British Cabinet on conversations held in Berlin between John Simon, Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, and Adolf Hitler, German Chancellor and Führer (March 1935).

John Simon thanked the Chancellor for the opportunity he had had of meeting him and for the way in which the British Ministers had been welcomed. But, observing the rule of frankness to the end, he must say that the British Ministers felt somewhat disappointed that it had not been possible to get a larger measure of agreement. They regretted that such difficulties were thought to exist on the German side in connection with some of the matters discussed. He did not regret having come to Berlin. He was sure that this meeting was the best way of continuing this investigation into the various points of view. What he regretted was that they had not been able to do more in the direction of promoting the general agreement which he was sure both sides wanted.

It showed that these things were more difficult and complicated than many believed them to be from a distance...

Hitler was also grateful to the British Government for the loyal efforts they had made in the matter of the Saar vote, and for all the other matters on which they had adopted such a loyal and generous attitude to Germany.

Source J

Bernard Partridge, a cartoonist, depicts Adolf Hitler and John Simon in the cartoon “Prosit!” [Cheers!] in the British satirical magazine Punch (27 March 1935).

The wording on the tankard is “Conscription” and in the caption it is:

Herr Hitler: “The more we arm together the peacefuller [more peaceful] we’ll be!”

Sir John Simon: “Well—er—up to a certain point—and in certain cases— provisionally—perhaps.”

Source K

Christian Leitz, an historian specialising in the Third Reich, writing in the academic book Nazi Foreign Policy, 1933–1941. The Road to Global War (2004).

Hitler’s quest to rearm Germany continued unopposed. During Anglo–French

talks in London at the beginning of February (1935), Germany’s

rearmament had received the blessing of the two West European powers

even though they still hoped to convince Germany to join a multilateral

Locarno-style pact guaranteeing the borders of Germany’s East European

neighbours.

Hitler’s answer to these conciliatory approaches came quickly. He

removed one of the major limitations of the Versailles Treaty and, on 16

March 1935, increased the size of Germany’s armed forces to 300,000

troops. This time, however, France, Britain and Italy seemed keen to

react more firmly to the worrying growth in Germany’s strength. At

Stresa in April, an attempt was made to establish a common front against

Germany’s increasing attempts to revise [post-war settlements].

However, the reaction of the three former allies remained meek [feeble].

To the delight of the Nazi regime, the common front against Germany was

both short lived and of limited impact. By June, Britain broke with

Stresa when it agreed to a bilateral naval agreement with Germany.

[Source: reproduced from NAZI FOREIGN POLICY 1933 – 1941, 1st Edition by

Christian Leitz, published by Routledge. © Routledge Christian Leitz,

reproduced by arrangement with Taylor & Francis Books UK.]

Source L

Henri Lichtenberger, a university lecturer, writing in the academic book The Third Reich (1937).

Confronted by the German desire for naval rearmament, England [Britain],

after a brief suggestion of displeasure, quickly decided to come to

terms. British leaders believed that the best way to safeguard this

primary English [British] interest would be to conclude a direct and

separate agreement with Germany which would set a maximum limit to

German armaments acceptable to both countries. In agreeing to this

transaction Germany not only received the right to begin, with English

consent, an important programme of naval construction, but also

potentially caused further disagreement among the signatories of the

Versailles Treaty.

The naval agreement signed in London on June 18, 1935 between England

and Germany aroused great concern in France. It was the occasion for

outbursts in the press and for diplomatic manoeuvres intended to

moderate the disagreement which had unexpectedly developed between the

two allied

nations, and hold together the Entente which was considered valuable. It

was nevertheless obvious that by his bold initiative, Hitler had scored

an amazing success which also strengthened his prestige in Germany. He

had won the right to rearm officially both on land and on sea and this

was accomplished without a violent break with France.

9. (a) What, according to Source I, were the conclusions reported to the

British government regarding the March 1935 meeting in Berlin? [3]

(b) What does Source J suggest about Anglo-German relations in 1935? [2]

10. With reference to its origin, purpose and content, analyse the value

and limitations of Source I for an historian studying the international

response to German aggression. [4]

11. Compare and contrast what Sources K and L reveal about the attitudes towards German foreign policy under Hitler. [6]

12. Using the sources and your own knowledge, discuss the effectiveness

of the international response to German aggression between 1933 and

1938. [9]

Example of timed in-class paper from an outstanding former student who scored a final grade of 7 for the course (click to enlarge):

Source I

In the anti-Japanese war, the Chinese people would have on their side greater advantages than those the Red Army has utilised in its struggle with the Guomindang. China is a very big nation, and ... if Japan should succeed in occupying even a large section of China, getting possession of an area with as many as 100 or even 200 million people, we would still be far from defeated ...

As for munitions, the Japanese cannot seize our arsenals [military stores] in the interior, which are sufficient to equip Chinese armies for many years, nor can they prevent us from capturing great amounts of arms and ammunitions from their own hands ...

Economically, of course, China is not unified. But the uneven development of China’s economy also presents advantages in a war against the highly centralised and highly concentrated economy of Japan ... It is impossible for Japan to isolate all of China: China’s Northwest, Southwest, and West cannot be blockaded by Japan.

The central point of the problem becomes the mobilisation and unification of the entire Chinese people and the building up of a united front.

[Source: Marxists Internet Archive (2014)]

Source J

In December 1936, Jiang [Jieshi] flew up to Xian in Shaanxi province to press upon Zhang Xueliang the urgency of completing the “annihilation” of the Communists before confronting the Japanese.

Upon arrival he was kidnapped by Zhang, who had been influenced by the Communists’ argument

that the Chinese were shamefully fighting other Chinese at a time when Japan threatened ... At this point, the Soviet Union intervened. Stalin sent a telegram to the Chinese Communists declaring that unless they arranged for the release of Jiang he would publicly renounce them as Communists and declare them to be mere “bandits”. Finally, an agreement was worked out between the Communists and the Guomindang. Jiang declared that he would firmly lead the national resistance against any further Japanese demands, and the Communists committed their forces to operating under the national command and promised to cease their partisan revolutionary propaganda. Jiang was released on Christmas Eve, 1936, and the Chinese nation seemed again to be moving towards genuine national unity.

[Source: authorised by the children of Lucian and Mary Pye]

Removed for copyright reasons which doesn't stop the IBO from taking money for this exam.

Source L

David Low, a political cartoonist, depicts the Japanese occupation of China in the cartoon “The Red Carpet” for the British newspaper the Evening Standard (14 June 1935). The writing on the carpet is “Japanese World Power”. The figures with their backs to the carpet represent Britain, France and the US.

Student example which received FULL MARKS (click to enlarge):

May 2021

The

sources and questions relate to case study 2: German and Italian

expansion (1933–1940) — Causes of expansion: impact of Fascism and

Nazism on the foreign policies of Italy and Germany.

Fascism and Nazism express the parallel historical situations which link the life of our nations ...

The

Rome–Berlin Axis is not directed at other states, because we, Nazis and

Fascists alike, want peace and are always ready to work for a real

fruitful [productive] peace which does not ignore but resolves the

problems of the coexistence of peoples ...

Source K

Removed

for copyright reasons which doesn't stop the IBO from taking money to

provide this exam for teachers. Had to hunt down the original source to

provide the extract here, although the IBO failed to properly quote the

actual extract correctly:

Stephen H. Roberts, an Australian historian, writing after his visit to Nazi Germany in the academic book The House That Hitler Built (1937)

Italy and Germany have been flung together by a general antagonism to their foreign policies. Mussolini has steadily supported Hitler in his treaty-breaking... The two governments were shown to have a certain identity of views on such matters as Spain, Russia, and rearmament; but the Axis remained very uncertain... [in fact, the actual extract reads: "threatened ‘ vertical axis ’ (from Berlin to Rome) remained very nebulous after the interviews."]

The basic truth is that the Germans have little faith in Italy’s fighting power, and they feel that events in Spain support their estimate. Moreover, the two countries are in harmony only because of their common enemies. Their policies conflict in so many essentials, and difficulties are avoided only by not being mentioned. Central Europe is a permanent barrier between them, so much so that it is difficult to envisage an Italo-German bloc based on a permanent identity of interests, however much their present isolation may force the two countries together... Yet it would be erroneous to preclude any possibility of united action between the two on such general grounds. An immediate threat might draw them together, despite Mussolini’s critical estimate of Hitler, and despite the German feeling about the Italians.

The Italians are not popular in Germany, but Germany is not in a position to pick and choose her friends, and she at least knows that Mussolini believes in the efficacy of swift blows and will not hesitate to use force in settling international disputes. The understanding between the two totalitarian States then, however uneasy it may be, dominates international affairs for the moment.

Source L

Hitler’s

determination to rearm and to revise the terms of [the Treaty of]

Versailles inspired Mussolini to revitalise Fascist foreign policy and

to reconsider his strategy for imperial expansion. He wanted to

integrate Fascist Italy’s ideological motives with its strategic

objectives. Although Fascist Italy retained its strategic and economic

interests in southern and east‐central Europe, Mussolini increasingly

appreciated that an extensive Italian empire in the greater

Mediterranean region could exist alongside a German‐ dominated continent

but would directly conflict with British and French vital interests.

The possibility

of becoming a strategic and ideological partner with

Nazi Germany, which could challenge Britain and France to the north and

help Italy achieve its imperial ambitions to the south, steadily

encouraged Mussolini ...

As Nazi Germany had influenced Fascist

foreign policy, Italy’s Mediterranean ambitions motivated a

reconsideration of German strategy. The basis of Hitler’s foreign policy

was the concept of a central European economic bloc with Germany at its

core. Mussolini’s Mediterranean ambitions and willingness to challenge

Britain and France worked to Germany’s strategic advantage: an

Anglo‐French‐Italian tension or conflict in the Mediterranean would

facilitate Germany’s military conquest of Central and Eastern Europe.

For this strategic reason as well as the close ideological affinities

[connections] between German National Socialism and Italian Fascism,

Hitler supported and demonstrated extraordinary loyalty to Mussolini

before and during the war.

Both Governments will endeavour to conclude among American, British, Chinese, Japanese, the Netherlands and Thai Governments an agreement in which each of the Governments would pledge itself to respect the territory of French Indochina.

The Government of Japan will withdraw all military, naval, air and police forces from China and from Indochina.

The Government of the United States and the Government of Japan will not support militarily, politically, or economically any Government or regime in China other than the national Government of the Republic of China.

The IBO conveniently removed the source for copyright reasons and incorrectly identifies the Japanese character as Hirohito- without any support at all.

Source L

General Tojo later explained that the decision to attack was adopted in view of the tense international situation due to the economic sanctions imposed by the United States, Britain and the Netherlands. American and British preparations for war, difficulties in the negotiations with the United States, and no clear means of settling the China Incident also contributed. It was therefore necessary to prepare for war and yet continue the diplomatic conversations. The deadline for the negotiations was set because November would be the best month for landing operations. December would be possible but difficult, January would be impossible because of the northeast monsoons. Japan wanted the United States to express its views regarding three major points of difference between the two governments: (1) the withdrawal of troops from China, (2) Japan’s commitments under the Tripartite Pact, and (3) equal access to international trade. Japan avoided specific commitments on all major issues, and so did the United States. In Japanese eyes, the United States Government was not willing to give the specific answers that Japan was looking for. Thus, negotiations were getting nowhere.

9. (a) What, according to Source I, were the proposals made to Japan by the United States? [3]

(b) What does Source J suggest about the attack on Pearl Harbour? [2]

10. With reference to its origin, purpose and content, analyse the value and limitations of Source I for an historian studying relations between Japan and the United States before the attack on Pearl Harbour. [4]

11. Compare and contrast what Sources K and L reveal about why the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbour in December 1941. [6]

12. Using the sources and your own knowledge, discuss the reasons for the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbour in 1941. [9]

Read sources |to L and answer questions 9 to 12. The sources and questions relate to case study 2: German and Italian expansion(1933-1940)— Causes of expansion: Appeasement.

Source I

Source K

Most of the sources were "Removed for copyright reasons" so yet again even after paying the IBO I still had to hunt down an actual copy:

Source K

The situation in China today is the direct result of Japan’s political policy rather than the pressure of her economic problems. Since 1931, it has become obvious from Japan’s policy of conquest that “security” and “self-defence” mean control of Chinese resources and territory. In recent years, the overpopulation argument has been effectively used to justify Japanese expansion because of its emotional appeal, but this has no real basis in economic reality. In 1931, the Japanese people were told that the occupation of Manchuria would solve their economic problems. They were disappointed. After six years Japan had not benefited from Manchuria, but she had to invest heavily there for military purposes. Unfortunately, in Japan political policy dictates economics. The result is that Japanese militarists have overcome the opposition of liberals and have gone far in deciding government policy. Although China is by far the greater sufferer economically, Japan has not escaped the consequences of the war. Japan’s military operations are becoming more expensive as her armies expand further into China. 75 % of the gasoline Japan used in 1936 for tanks, bombers and warships came from the United States. One-third of the steel Japan produced in 1937 came from American raw materials.

Source I for an historian studying the reasons for Japanese expansion in the 1930s. [4]

motives for expansion in East Asia. [6]

Read sources I to L and answer questions 9 to 12. The sources and questions relate to case study 2: German and Italian expansion (1933-1940) - Responses: International response to German and Italian aggression (1940).

Source I

Winston Churchill, Prime Minister of Great Britain [and northern Ireland, IBO], in a letter to Franklin D Roosevelt, President of the United States of America, marked secret and personal (7th December 1940).

Dear Mr. President

It seems to me that the vast majority of the American people are convinced that the safety of the United States as well as the future of our two democracies are dependent upon the survival and independence of the British Commonwealth. The control of the Pacific by the United States Navy and of the Atlantic by the British Navy is essential to the security of our trade routes and the best way of preventing the war spreading to the shores of the United States. The urgent need is to limit the loss of shipping on the Atlantic routes to our islands. This may be achieved by increasing the naval forces which deal with enemy attacks. The gift, loan or supply of a large number of American warships, above all destroyers already in the Atlantic, is vital to the maintenance of the Atlantic route. The United States Navy also needs to ensure that protection is given to the new bases that the United States is establishing in British islands in the Western Hemisphere.

Source J

Source K

Andrew Roberts, an historian, writing in the academic book The Storm of War (2009).

It has been claimed that between June 1940 and June 1941 the British were completely alone [after the fall of France]. This is not true, as they had the support of the British Commonwealth and Empire, as well as their alliance with Greece. However, there was very little to oppose a German invasion of Britain if this had come in 1940. Roosevelt largely rearmed the British army after Dunkirk. Before the United States entered the war, the Roosevelt Administration had provided Britain with invaluable help. As well as allowing Britain to buy much needed arms and other supplies, the United States had given the Royal Navy fifty destroyers in return for long leases on various British military bases in September 1940, and had begun patrolling areas of the Western Atlantic against U-Boats. Roosevelt continually sent encouraging support to Churchill and [through 1940] pushed for the Lease-Lend Act until it was passed in 1941. Britain had maintained its freedom by resisting alone. Other countries tried to preserve their freedom by declaring their neutrality. These include Turkey, Portugal, the Republic of Ireland, Sweden and Switzerland. However, Switzerland allowed German and Italian military supply trains to pass through its country, while in July 1940 Sweden gave Germany the right to move troops over her borders.

Source L

Max Hastings, an historian, writing in the academic book Finest Years: Churchill as Warlord 1940-45 (2009).

On May 2nd, 1940, Churchill appealed for American aid and begged for the loan of fifty destroyers. Roosevelt decided that this would breach the 1939 Neutrality Act and vetoed the request. The language used by Roosevelt and Churchill created a myth of American generosity in 1940 and 1941. Cordell Hull, the US Secretary of State, wrote of supplying vast quantities of weapons to Britain in the summer of 1940. However, the value of these shipments made a minimal contribution to Britain's fighting power. American-supplied artillery and small arms were obsolete. The fifty old destroyers loaned by the US in September 1940 in exchange for British colonial bases were of little practical value. At the end of 1940, only nine of the destroyers were operational and US guns, tanks and planes shipped across to Britain were not gifts. Under the terms of the Neutrality Act imposed by Congress, war materials had to be paid for in cash resulting in huge profits for US companies from arms sales. Roosevelt told the British Ambassador to Washington that there could be no American subsidy [financial support] while Britain could still pay, as Congress would never allow it... Relations between the dominions and London were poor, often because Churchill treated colonial governments of the Commonwealth and Empire with indifference.

Read sources I to L in the source booklet and answer questions 9 to 12. The sources and questions relate to case study 2: German and Italian expansion (1933-1940)-Responses: International response to German and Italian aggression (1940).

9. (a) What, according to Source I, should the United States do to support Britain? [3]

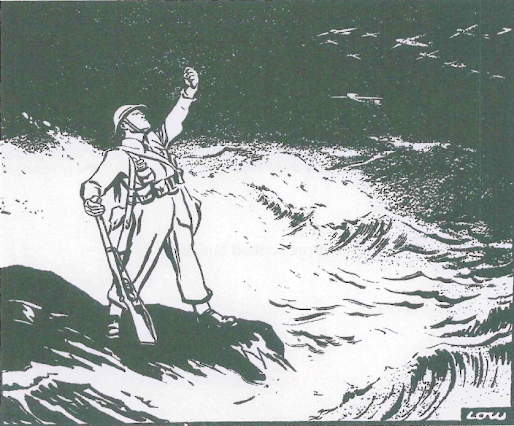

(b) What does Source J suggest about Britain's situation in June 1940? [2]

10. With reference to its origin, purpose and content, analyse the value and limitations of Source I for an historian studying the British response to German and Italian aggression in 1940. [4]

11. Compare and contrast what Sources K and L reveal about international responses to German and Italian aggression. [6]

12. Using the sources and your own knowledge, evaluate the extent of international support for Britain in 1940. [9]

Sample example from student under exam conditions:

November 2024

The sources and questions relate to case study 2: German

and Italian expansion (1933–1940) — Causes of expansion: Impact of

fascism and Nazism on the foreign policies of Italy and Germany.

Source I

Benito

Mussolini, Prime Minister of Italy, giving a speech to the people of

Rome after Italy’s declaration of war (10 June 1940).

Fighters

on land, sea, and air. Blackshirts of the revolution. Men and women of

Italy, of the Empire, listen! The hour has come. The declaration of war

has already been delivered to the ambassadors of Great Britain and

France.

We go to war against Great Britain and France, who always

have blocked the progress and often plotted against the existence of the

Italian people ...

Fascist Italy did everything humanly possible to

avoid war by proposing to revise and adapt treaties. But with no

success, and now it is too late ...

We take up arms to break the

chains of territorial and military constraints that confine us to the

Mediterranean, for we are not truly free unless we have free access to

the Atlantic Ocean ...

According to Fascist morality, we march with Germany, with its people, with its victorious Armed Forces to the end ...

Italian people! Take up arms!

Source J

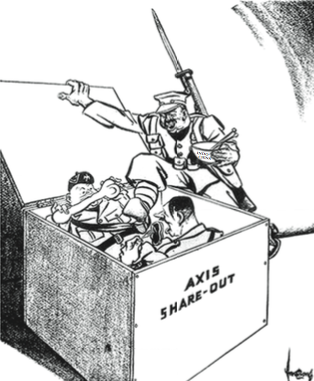

Clifford Berryman, a cartoonist, depicts Hitler and Mussolini in the cartoon “Telling

the

Italians!” for The Washington Star (4 April 1938), following the German

annexation of Austria in March 1938. Hitler is carrying Austria in a

bag labelled “Austria in the bag”, while Mussolini is proclaiming “I

planned it that way and Adolf carried it out!”

Source K

Jeremy Noakes and Geoffrey Pridham, historians, writing in the academic book Nazism 1919-1945 Volume 3 (2001).

Nazi foreign policy consisted of several stages. A key stage was the defeat of France militarily, securing Germany's western border and allowing the creation of lebensraum in the East. The assassination of Dollfuss in 1934 by Nazis in Vienna produced serious diplomatic complications with Italy when Mussolini ordered troops to the Austrian border. However, Mussolini was becoming convinced that an alliance with Germany offered the best opportunities for Italian expansion. In response to the actions of the Western powers over Abyssinia, Mussolini indicated that Italy would take no action if Germany were to reoccupy the Rhineland, which it did in March 1936. The final victory of Italy over Abyssinia in May 1936 boosted Mussolini's self-confidence as he gave his blessing to the Austro-German agreement signed on July 11 1936, acknowledging Austrian independence. In July 1936 a civil war broke out in Spain which polarized opinion in Europe and firmly merged the ideologies of Germany and Italy together. On 1 November 1936, Mussolini formally announced the establishment of a Rome-Berlin axis, maintaining that Germany had recognized the Empire of Rome and that Germany had no wish to interfere in the Mediterranean theatre of war.

Source L

Christian Goeschel, an historian, writing in the academic book Mussolini and Hitler: The forging of the Fascist alliance (2018).

Hitler saw Mussolini as a strong and determined leader who had rescued Italy from the left and turned it into a powerful dictatorship. However, the ideological impact of Fascism on Nazism was quite minor, as Nazi ideology had already been formulated in the Nazi party manifesto of 1920 and Mein Kampf. There were some considerable ideological differences between the two regimes.

After Hitler's appointment as Chancellor, relations between Italy and Germany remained tense, partly because Hitler wanted to extend his control over Austria whose sovereignty was guaranteed by Fascist Italy. But Hitler's consolidation of the Third Reich and a series of stunning foreign policy successes, notably the remilitarisation of the Rhineland, elevated Hitler to be the leading light of European Fascism. Italy's occupation of Abyssinia, the subsequent League of Nations sanctions and the Spanish Civil War resulted in the politics of Italy and Germany becoming increasingly entangled with each other. For Mussolini, an alliance with the now more powerful Germany was a way to enhance his prestige and transform Italy into a totalitarian nation Overall, Mussolini's goal was to establish Italy as the dominant power in the Mediterranean, expanding the empire to create living space (spazio vitale). Mussolini's proclamation of the Rome-Berlin axis in November 1936 realised this ambition However, no formal alliance was signed and Italy did not enter the Second World War on Germany's side until June 1940.

9. (a) What, according to Source I, were the reasons for Italy to declare war on Britain and France? [3]

(b) What does Source J suggest about relations between Italy and Germany in 1938? [2]

10. With reference to its origin, purpose and content, analyse the value and limitations of Source I for an historian studying Italian foreign policy in 1940. [4]

11. Compare and contrast what Sources K and L reveal about German and Italian foreign policy in the 1930s. [6]

12. Using the sources and your own knowledge, to what extent were the foreign policies of fascist Italy and Nazi Germany, up to 1940, influenced by their territorial ambitions? [9]

May 2025

Read sources I to L and answer questions 9 to 12. The sources and questions relate to case study 2: German and Italian expansion (1933-1940) - Events: German expansion (1938-1939); Nazi-Soviet Pact and the outbreak of war.

Source l

A.J.P Taylor, a British historian, writing in the academic book The Origins of the Second World War (1961).

The Nazi-Soviet Pact was not an alliance nor was it an agreement for the partition of Poland. The Soviets only promised to remain neutral, which is what the Poles had always asked them to do and what the Western powers also wanted. In fact, in August 1939 the Russians were not thinking in terms of war. They assumed, like Hitler, that the western powers would not fight to defend Poland without a Soviet alliance. Poland would be forced to surrender and an alliance between Russia and the West might then be achieved.

Both Hitler and Stalin imagined that they had prevented war when they signed the Nazi-Soviet Pact, not provoked it. Hitler thought that he would be granted another Munich Agreement over Poland; Stalin believed that he had even avoided war altogether.

However, these predictions were eventually proven false, as a war began in which both Poland and the Western powers took part. This was a success for the Soviet leaders, as it prevented what they had most feared a united capitalist attack on Soviet Russia. On the other hand, the pact affected Germany's ability to wage war, as it limited its advance to the east, into Soviet Russia.

Source J

Kimon Evan Marengo, a British/Egyptian cartoonist, depicting Hitler and Stalin in a political poster titled The Progress of Russian and German Cooperation (1939).

Source K

An editorial in The Guardian, a British newspaper, commenting on the signing of the Nazi-Soviet Pact (2 September 1939).

On the night of Monday, 21 August, it was announced in Berlin that a pact of non-aggression would shortly be signed between Germany and Russia. Herr Hitler and his advisers believed that the announcement of the Pact would cause Britain and France to abandon Poland to her fate.

However, on 22 August, the day after the Pact was announced, Mr. Chamberlain sent a letter to Herr Hitler assuring him that Britain would stand by Poland no matter what the Pact contained. He also added his belief that the dispute between Poland and Germany could be settled by peaceful negotiation and suggested a truce for that purpose.

On the next day, 23 August, Herr Hitler replied that while he was anxious to win the friendship of Britain, he could not recognise Britain's right to interfere in matters relating to the German 'sphere of interest' in Eastern Europe.

On the morning of 24 August the Pact between Russia and Germany was signed and a German attack on Poland seemed probable at any moment.

Source L

Jane Caplan, a professor, writing in the book Nazi Germany: A Very Short Introduction (2019).

The Munich Agreement was abandoned in March 1939, when Hitler invaded what was left of Czechoslovakia. Hitler's actions led Britain and France to issue a guarantee to Poland, where Germany was trying to gain more territory.

Months of diplomatic activity followed, in an atmosphere full of miscalculation and distrust. France, Britain, Poland and the Soviet Union were urgently seeking security wherever it might be found. However, Germany's case was different, as Hitler's strategy was to create the most ideal conditions for war.

As he planned the attack on Poland, Hitler had to accept simultaneous conflict in the west would now be inevitable. However, on 23 August, Nazi Germany and Soviet Russia signed an astonishing non- aggression Pact that would secure the eastern front after Poland's defeat and allow the German troops to turn safely westward. This Pact was accompanied by a secret agreement detailing the Nazi and Soviet 'spheres of interest' in Poland and the Baltic states.

Buying time and benefits

for both parties, the Pact was the introduction to invasion.

1. (a) What, according to Source L, were the effects of the Nazi-Soviet Pact? [3]

(b) What does Source J suggest about the Nazi-Soviet Pact?

2. With reference to its origin, purpose and content, analyse the value and limitations of Source K for an historian studying the impact of the Nazi-Soviet Pact on the outbreak of war.

3. Compare and contrast what Sources I and L reveal about the Nazi-Soviet Pact. [6]

4. Using the sources and your own knowledge, to what extent did the Nazi-Soviet Pact lead to the outbreak of war? [9]

Very grateful to my top student for providing me with his IBO-graded final exam for which

he scored 22/24; one can see IBO examiners don't even bother writing

comments anymore which explains why there's so much disparity in quality

of grading today:

I'm equally grateful to another senior for also obtaining and providing his response, graded by the IBO which received 21/24.

![Bernard Partridge, a cartoonist, depicts Adolf Hitler and John Simon in the cartoon “Prosit!” [Cheers!] in the British satirical magazine Punch (27 March 1935).](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjWPaPtsAtmiH49RQzSlbJFsInDK0V1jnKetdCjdIUqaI_rwL-E-h32f203OmeJk3UN69EuCzq04syX19gLsrLUtLPcUJWMH6L0uEX71xJh1n1v27F6p9nNobWtEvOwZvGLXZ1leXdcSYhF/w283-h400-rw/Screen+Shot+2019-12-10+at+12.12.43.png)