Heilbronn

In front of the town hall in July 2022 and when it was bedecked in swastikas. Richard

Drauz became Heilbronn's Kreisleiter in 1932. He was also elected to

the Reichstag from 1933 on (when the town voted 31.6% Nazi- considerably

lower than the national average) and pushed hard for the

Gleichschaltung of the Heilbronn clubs and press in Nazi Germany. On

March 7, 1933, the SPD-newspaper "Neckar-Echo" was last published with

the title "Forbidden"; the printing shop on the site of a shopping

centre today was occupied on March 12 and made to print the Nazis'

"Heilbronner Tagblatt." The Nazi takeover was celebrated for the first

time on March 16, 1933 in the town council in which only 17 of its thirty

town councillors were present after three KPD city councils were

deprived of their office, two SPD councillors beaten and prevented from entering

the town hall, and eight forced into protective custody. On that date

applications such as the renaming the alley Adolf-Hitler-Allee were

accepted whilst nevertheless refusing to deprive the Jewish lawyer Max

Rosengart and Jewish city councillor Siegfried Gumbel of their honorary

citizenship.

|

| The town hall sporting swastikas and today |

In front of the Nazi eagle still remaining on Rosenberg Bridge; the other side as another eagle with the date 1939-1939.

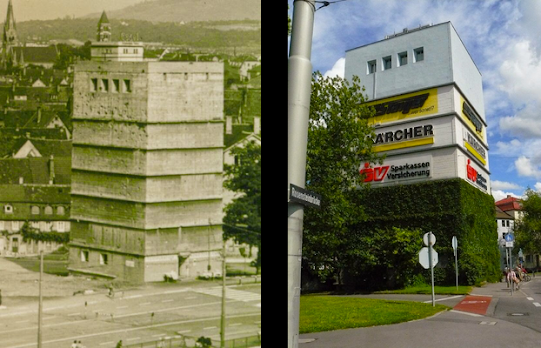

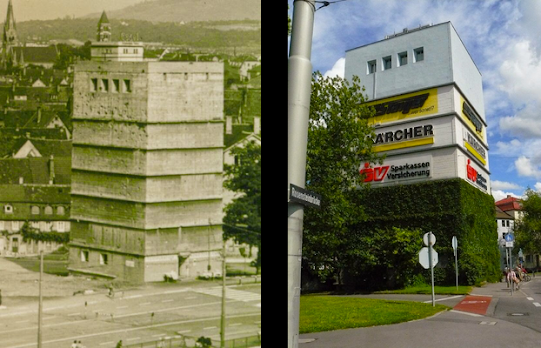

In front of an example of the the only wartime high-rise bunker in Heilbronn located

at the Theresienwiese and a similar type from Rüsselsheim for

comparison. It was built by Dyckerhoff & Widmann on behalf of the

Air District Command VII (Munich) in October 1940. Clad with sandstone

on the outside, the municipal slaughterhouse was intended to be the main

user, which is surprising given the very military equipment of the

building.Of the ten floors, six were designed as crew rooms for 42 men

each. Each of these crew rooms was equipped with two toilets, a sink,

three bunk beds with three floors and lockers. On the lowest floor was

the filter and ventilation system, a water pressure boiler with a well,

two diesel tanks and a 50 HP diesel unit from MAN. The generated

voltages of 400 volts and 62 volts were converted using a separate

transformer. The entrances were on the second and third floors and were

accessible via stairs and a catwalk leading across the street to the

slaughterhouse. In the event of an air alarm, the building could

accommodate around a thousand people. After the war it served as

emergency accommodation for a short time before it was closed in 1948.

In

1940 allied air raids began, and the city and its surrounding area were

hit about 20 times with minor damage. On September 10, 1944, a raid by

the allies targeted the city specifically, in particular the Böckingen

train transfer station. As a result of 1,168 bombs dropped that day, 281

residents died. The city was carpet-bombed from the southern quarter

all the way to the Kilianskirche in the centre of town. The church was

burnt out. The catastrophe for Heilbronn was the bombing raid on

December 4, 1944. During that raid the city centre was completely

destroyed and the surrounding boroughs heavily damaged. Within one half

hour 6,500 residents perished, most incinerated beyond recognition. Of

those, 5,000 were later buried in mass graves in the Ehrenfriedhof

(cemetery of honour) in the valley of the Köpfer creek close to the

city. A memorial continues to be held annually in memory of those that

died that day. As a result of the war Heilbronn's population shrank to

46,350. After a ten-day battle, with the allies advancing over the

strategically important Neckar crossings, the war ended for the

destroyed city, and it was occupied by the Americans on April 12, 1945.

Local Nazi leader Drauz became a fugitive because of executions of

American prisoners of war he had ordered in March 1945. He was

eventually arrested, tried, and hanged by the Allies in Landsberg on

December 4, 1946.

The

Nazi flag flying atop the Kiliansturm for the first time January 30-31,

1933 and the resulting damage to Kilianskirche after the war. Already

on September 10, 1944, the roofs of the choir, the northern side nave

and the sacristy were destroyed by fire bombs during an American air

attack. On October 12, 1944, an airmine destroyed the windows, parts of

the chimneys, the southern spiral staircase, and part of the the high

altar. On December 4, 1944, the church was almost completely destroyed

during the air attack on Heilbronn. The western tower and the northern

Chorturm burned out, whilst the choir with net vault, the gallery and

the organ were completely destroyed. In April 1945, strong American

artillery fire continued to inflict further damage, particularly on the

West Front.

The

Nazi flag flying atop the Kiliansturm for the first time January 30-31,

1933 and the resulting damage to Kilianskirche after the war. Already

on September 10, 1944, the roofs of the choir, the northern side nave

and the sacristy were destroyed by fire bombs during an American air

attack. On October 12, 1944, an airmine destroyed the windows, parts of

the chimneys, the southern spiral staircase, and part of the the high

altar. On December 4, 1944, the church was almost completely destroyed

during the air attack on Heilbronn. The western tower and the northern

Chorturm burned out, whilst the choir with net vault, the gallery and

the organ were completely destroyed. In April 1945, strong American

artillery fire continued to inflict further damage, particularly on the

West Front.

As of today, anti-Semitism has made reappearance, especially with the huge influx of Muslims by the Merkel government with the latest attack occurring at 21.45 on Christmas Eve 2017 when the three-metre-high Hanukkah Menorah in the alley of Synagogengasse had been vandalised with several lamps and their glass cartouches knocked off.

As of today, anti-Semitism has made reappearance, especially with the huge influx of Muslims by the Merkel government with the latest attack occurring at 21.45 on Christmas Eve 2017 when the three-metre-high Hanukkah Menorah in the alley of Synagogengasse had been vandalised with several lamps and their glass cartouches knocked off.

Schwäbisch Gmünd

The Nazis had only

achieved only 26% of the votes cast in Gmünd during the last somewhat

free Reichstag elections in March 1933 which came well below the

national average of 44%. In breach of the constitution, the results of

these elections were now transferred to the state and local councils,

so that Gmünd's local council had to be newly formed in April 1933

resulting in the Nazis getting eight seats from their previous two

whilst, the Catholic Centre Party enjoyed eleven seats with the

remaining three from other parties. In the course of the

"Gleichschaltung", the non-Nazi councillors were forced to

resign so that from April 1934 the Nazi Party represented the council

alone. In November 1934, the unelected Nazi Franz Konrad was simply appointed Lord Mayor. The Nazi Party district leader, Hermann

Oppenländer, was charged with mobilising the population for the goals of

the party from 1937 onwards. This included of course the harassment of

Jewish citizens. Those few who still lived in Gmünd were penned into the

two houses that were still owned by Jews at Kornhausstrasse 10 and

Königsturmstrasse 18. It was to get even worse in 1941 when the last ten Jews were sent to Becherlehen 1/2, a barrack referred to as

"Lüllig-Dorf". From there they were deported to the extermination camps

in the east. None of them survived. In all, a total of 22 Gmünd Jews are

known by name who were murdered by the Nazis.From the start as well,

laws were passed that allowed people with "hereditary diseases" to be

forcibly sterilised going on to murder the disabled and the mentally

ill. In Gmünd it's known that six citizens were euthenised.

The Nazis had only

achieved only 26% of the votes cast in Gmünd during the last somewhat

free Reichstag elections in March 1933 which came well below the

national average of 44%. In breach of the constitution, the results of

these elections were now transferred to the state and local councils,

so that Gmünd's local council had to be newly formed in April 1933

resulting in the Nazis getting eight seats from their previous two

whilst, the Catholic Centre Party enjoyed eleven seats with the

remaining three from other parties. In the course of the

"Gleichschaltung", the non-Nazi councillors were forced to

resign so that from April 1934 the Nazi Party represented the council

alone. In November 1934, the unelected Nazi Franz Konrad was simply appointed Lord Mayor. The Nazi Party district leader, Hermann

Oppenländer, was charged with mobilising the population for the goals of

the party from 1937 onwards. This included of course the harassment of

Jewish citizens. Those few who still lived in Gmünd were penned into the

two houses that were still owned by Jews at Kornhausstrasse 10 and

Königsturmstrasse 18. It was to get even worse in 1941 when the last ten Jews were sent to Becherlehen 1/2, a barrack referred to as

"Lüllig-Dorf". From there they were deported to the extermination camps

in the east. None of them survived. In all, a total of 22 Gmünd Jews are

known by name who were murdered by the Nazis.From the start as well,

laws were passed that allowed people with "hereditary diseases" to be

forcibly sterilised going on to murder the disabled and the mentally

ill. In Gmünd it's known that six citizens were euthenised. In

1933 there were ninety Jews recorded as living in Schwäbisch Gmünd,

which corresponds to 0.4% of the total of 20,131 inhabitants. Already

the year before SA propaganda parades called out "Germany awake - Judah

verrecke!" in the town's streets. Between 1936 and 1938 all Jewish shops

were forced to close, either sold off at knock-down prices or simply

forced out. The interior of the synagogue was demolished as early as

1934. By 1939 there were still 22 Jewish inhabitants who were forced

into special "Jewish houses" at the beginning of the war located at

Königsturmstrasse 18 and Becherlehenstrasse 1/2. Eventually they would

be forced into the "Lülligdorf", a basic settlement for homeless people

from the 1920s on Mutlanger Strasse. From here the remaining Jewish

residents were transported to the extermination camps.

Just before Gmünd was

taken by the Americans on April 20, 1945- Hitler's birthday- without

bloodshed, Nazi

district leader Oppenländer fled along with his colleagues- but not

before committing acts of terror against their own population as Ian

Kershaw relates in The End:

In Schwäbisch Gmünd, a small town in Württemberg not far from Stuttgart, the Kreisleiter and combat commandant had two men executed just before midnight on 19 April, hours before the Americans entered the town without a fight. One of the men was known to have been an opponent of the Nazis since 1933, when he had been arrested for distributing anti‑Nazi pamphlets and returned from his stay in a concentration camp a changed person, psychiatrically disturbed. The other was a former soldier, no longer fit to fight after a serious injury. In a heated argument about handing over the city or fighting on, with the certainty of the destruction of the lovely town with its beautiful medieval minster, they had been heard to shout, probably under the influence of alcohol, ‘Drop dead Hitler. Long live Stauffenberg. Long live freedom.’ The two were removed from their police cells late at night, taken to a wood at the edge of the town and shot dead. The local Nazi representatives were ensuring, with their last act of power, that long‑standing opponents would not live to enjoy their downfall. Even as the executions were taking place, the Kreisleiter and his entourage were preparing to flee from the town.

Under Lieutenant Mortimer, the Americans immediately set up

their military government, which consisted of eight officers and fifteen

soldiers, initially at Villa Koehler. They had unrestricted authority

to issue instructions to the German authorities and the head of the tax

office, Emil Rudolph, was appointed acting mayor and the operations

manager of the Deyhle company, Konrad Burkhardt, was appointed district

administrator. In addition to supplying the population with food and

energy, the repatriation of the now liberated forced labourers posed a

major problem as many used their new freedom to plunder isolated farms.

Around ten thousand Poles, Balts and Ukrainians were housed in the two

barracks and in Gotteszell- a women’s prison on the grounds of a monastery- before being repatriated. Above all the

Americans saw their most important task in denazification, through which

all officials, who usually had to be members of the Nazi Party, were

automatically arrested, so that around 100,000 people were held in

internment camps throughout the American zone. In March 1946, the

denazification was placed into German hands and those affected had to

answer before the ruling chambers in a court-like procedure.

One

unmistakeable reminder of the Nazi era is the war memorial that towers

over the market square, shown here in a Nazi-era postcard and today with my bike in front.

Although the swastika that topped it has been

simply replaced with a statue of St. Michael, it is covered in Nazi

iconography including Hitler salutes. It was created by sculptor Jakob

Wilhelm Fehrle and inaugurated on November 9, 1935, the twelfth

anniversary of the failed Beer Hall Putsch depicted in the painting

above. It was initially intended to

commemorate those who fell in the Great War and is made of 21 bronze

cast parts based on Trajan's column. Originally the column carried an

eagle with a swastika on its top but was replaced in 1952 by the Michael

statue placed on a ball, also made by Fehrle. During the tenure of

Mayor Franz Czisch, the entire column was dismantled in 1946 and stored

at the Gmünd freight yard. By this time given the loss of so many church

bells to the war effort and the severe shortage of materials in the

post-war period, in January 1948 the Gmünd authorities were requested

that the “bronze material of the war memorial be melted down in favour

of a peace bell.”

One

unmistakeable reminder of the Nazi era is the war memorial that towers

over the market square, shown here in a Nazi-era postcard and today with my bike in front.

Although the swastika that topped it has been

simply replaced with a statue of St. Michael, it is covered in Nazi

iconography including Hitler salutes. It was created by sculptor Jakob

Wilhelm Fehrle and inaugurated on November 9, 1935, the twelfth

anniversary of the failed Beer Hall Putsch depicted in the painting

above. It was initially intended to

commemorate those who fell in the Great War and is made of 21 bronze

cast parts based on Trajan's column. Originally the column carried an

eagle with a swastika on its top but was replaced in 1952 by the Michael

statue placed on a ball, also made by Fehrle. During the tenure of

Mayor Franz Czisch, the entire column was dismantled in 1946 and stored

at the Gmünd freight yard. By this time given the loss of so many church

bells to the war effort and the severe shortage of materials in the

post-war period, in January 1948 the Gmünd authorities were requested

that the “bronze material of the war memorial be melted down in favour

of a peace bell.”  Czisch

agreed, and applied to use the memorial for the “replacement of the

bells of the town hall and the hospital.” Most of the town council

seemed to agree to the proposal to donate the material from the former

memorial to the favour of a peace bell although councillor Böhnlein

called for more "old material to be retained for the tower clock of the

Schmidt tower." But

it was Dr. Hermann Erhard, owner and board member of Erhard &

Söhne, who was most influential in ultimately preserving the monument.

He wanted to “commemorate the 640 Gmünder soldiers who had fallen in

Gmünd” but felt the ringing of some 'peace bell' would have meant

nothing; for him [p]eace for citizens does not come about through

symbols of peace, instead through re-education in the hearts and minds

of the people" He advocated keeping the bronze material for the city and

in so doing brought another central point into the discussion. Erhard,

who had fought in the First World War, not only wanted to have his

fallen comrades formally commemorated, but also pointed to the "artistic

value"of the monument. He argued that “[t]he column be put up again

after the swastika was removed.” Ultimately his campaign was successful

as three Social Democrats abstained from the vote, possibly under the

impression that its reliefs were damaged after the monument's

demolition. And so, despite the mayor's wishes, the column

was not melted down but was put up again after he was voted out of

office. Today the column is said to be dedicated to the memory of the

thousand Gmünders who fell in both world wars- not to any German

victims.

Czisch

agreed, and applied to use the memorial for the “replacement of the

bells of the town hall and the hospital.” Most of the town council

seemed to agree to the proposal to donate the material from the former

memorial to the favour of a peace bell although councillor Böhnlein

called for more "old material to be retained for the tower clock of the

Schmidt tower." But

it was Dr. Hermann Erhard, owner and board member of Erhard &

Söhne, who was most influential in ultimately preserving the monument.

He wanted to “commemorate the 640 Gmünder soldiers who had fallen in

Gmünd” but felt the ringing of some 'peace bell' would have meant

nothing; for him [p]eace for citizens does not come about through

symbols of peace, instead through re-education in the hearts and minds

of the people" He advocated keeping the bronze material for the city and

in so doing brought another central point into the discussion. Erhard,

who had fought in the First World War, not only wanted to have his

fallen comrades formally commemorated, but also pointed to the "artistic

value"of the monument. He argued that “[t]he column be put up again

after the swastika was removed.” Ultimately his campaign was successful

as three Social Democrats abstained from the vote, possibly under the

impression that its reliefs were damaged after the monument's

demolition. And so, despite the mayor's wishes, the column

was not melted down but was put up again after he was voted out of

office. Today the column is said to be dedicated to the memory of the

thousand Gmünders who fell in both world wars- not to any German

victims.  Standing at the most remarkable site at Schwäbisch Gmünd- the very limit of the Roman Empire along the Raetian Limes. On the

top left is a visual representation from the Aalen museum of how it

would have appeared whilst below is an actual reconstruction at the

entrance to the park. Up until this point the Upper German Limes from

the Rhine to the Rotenbachtal here, northwest of Schwäbisch Gmünd,

consisted most recently of a rampart and a moat serving as a substitute

for a wooden palisade. During the last expansion phase, a continuous

stone wall was erected in the province of Raetia, from the Rotenbachtal

to the Danube at Ausina.

Standing at the most remarkable site at Schwäbisch Gmünd- the very limit of the Roman Empire along the Raetian Limes. On the

top left is a visual representation from the Aalen museum of how it

would have appeared whilst below is an actual reconstruction at the

entrance to the park. Up until this point the Upper German Limes from

the Rhine to the Rotenbachtal here, northwest of Schwäbisch Gmünd,

consisted most recently of a rampart and a moat serving as a substitute

for a wooden palisade. During the last expansion phase, a continuous

stone wall was erected in the province of Raetia, from the Rotenbachtal

to the Danube at Ausina.  That

this spot really does mark the transition from the Limes wall to the

Upper German palisade is strongly supported not only by the wall's

precisely constructed terminus, but by the fact that in front of it was

found the remains of an altar that was possibly dedicated to the fines,

or border deities, a replica of which I'm standing beside in front of

the wall and how it appeared when uncovered by Steimle at the end of the

19th century in the Rotenbachtal at the beginning of the Rhaetian Wall

near Kleindeinbach. It has four rosettes on the face of as many

bulges atop with no remains of inscriptions below the cornice beyond

seven radial grooves, apparently from the grinding of tools. This altar,

and the finished nature of the roughly hewn sandstone blocks of the

wall itself, provide considerable evidence that this section marked the

end of the Upper Germanic Limes and the start of the Rhaetian Limes.

Here from about 160 to 260 CE, the Rems Valley was the outermost border

zone of the Roman Empire, guarded by over 1,500 soldiers within the

Gmünd area stationed in cohorts in Lorch, at Schirenhof and Böbingen as

well as in some smaller facilities such as Freimühle, Kleindeinbach and

Hintere Orthalde.

That

this spot really does mark the transition from the Limes wall to the

Upper German palisade is strongly supported not only by the wall's

precisely constructed terminus, but by the fact that in front of it was

found the remains of an altar that was possibly dedicated to the fines,

or border deities, a replica of which I'm standing beside in front of

the wall and how it appeared when uncovered by Steimle at the end of the

19th century in the Rotenbachtal at the beginning of the Rhaetian Wall

near Kleindeinbach. It has four rosettes on the face of as many

bulges atop with no remains of inscriptions below the cornice beyond

seven radial grooves, apparently from the grinding of tools. This altar,

and the finished nature of the roughly hewn sandstone blocks of the

wall itself, provide considerable evidence that this section marked the

end of the Upper Germanic Limes and the start of the Rhaetian Limes.

Here from about 160 to 260 CE, the Rems Valley was the outermost border

zone of the Roman Empire, guarded by over 1,500 soldiers within the

Gmünd area stationed in cohorts in Lorch, at Schirenhof and Böbingen as

well as in some smaller facilities such as Freimühle, Kleindeinbach and

Hintere Orthalde.At the bath complex near Schirenhof fort a mile away, shown in 2008

and when I visited in 2021. The fort itself had been built around 150

CE halfway up a mountain spur with a view over the Rems to the Rhaetian

Limes. This structure had been excavated for the first time in 1893 and

was opened to the public in 1975 in this restored condition after new

excavations carried out during urbanisation. These excavations showed

that the Cohors I Flavia Raetorum, named on brick stamps and the

fragment of a genius statue, had been the main troop unit garrisoned

here after having been transferred either from Eislingen-Salach or

another unidentified fort in Raetia. Shortly after 247 at the latest,

the last soldiers left the place based on the evidence from Roman coins

discovered here in the fort’s bath.

Aalen

Aalen's

market square on Hitler's 50th birthday, 1939. In the Reichstag

election on November 6, 1932, the Nazis performed well below average in Aalen, receiving 25.8 percent of the vote compared to 33.1% in the rest

of the country, making it only the second strongest party in Aalen after

the Centre Party which had received 26.6 (compared to a mere 11.9 %

nationally) and ahead of the SPD's 19.8%. However, by the time of the

next national election on March 5, 1933, the picture had changed; whilst

the Nazis still performed below average with 34.1 percent compared to

43.9% nationally, it now became by far the strongest party in Aalen as

well and the Central and SPD parties' results remained unchanged. At the

beginning of the Nazi era, the democratically elected mayor Friedrich

Schwarz remained in office until he was ousted by the Nazis in the

council's first meeting of 1934 when SA-Sturmbannführer and member of the parliamentary group, Fridolin Schmid declared "[t]he

city is [now] ours and not yours, Lord Mayor!" He was replaced first by

the chairman of the Nazi Party council group and brewery owner Karl

Barth as administrator and later by lawyer Dr. Karl Schübel. After the

war as part of the denazification process, Schübel was classified in the

second instance in the group of followers. Nevertheless, in May 1950,

he was elected Lord Mayor of the Aalen with 87% of the votes cast from

from among three applicants, with a turnout of 81%. Election posters of

an opposing candidate, Peter Lahnstein, had been smeared with anti-Semitic slogans because of his Jewish descent.

The town centre during the Nazi era and today. In

1933 there were seven Jewish residents living in Aalen, two of whom

were children. During Kristallnacht in 1938, the shop windows of the

three Jewish shops in the town were shattered and the owners

subsequently imprisoned in the Dachau concentration camp for several

weeks. After their release, most of the Jews emigrated. Eduard and

Frieda Heilbron last lived in a so-called Judenhaus in Wiesbaden,

where Eduard Heilbronn died of a heart attack. His wife Frieda was

deported to Theresienstadt and later murdered in the Treblinka

extermination camp. Their daughter Irene survived, managing to emigrate

to Colombia with her husband Kurt Wartzki and their children. The last

Jewish resident, Fanny Kahn, was forcibly relocated to Oberdorf am Ipf in 1941, later deported and also murdered in. In 2005 a

street in Aalen was named in her honour. Of the town's Jews who were

murdered, Yad Vashem, records the names of Leopold Elter; Eduard, Frieda

and their son Willi Heilbronn; and Fanny Kahn.

The town centre during the Nazi era and today. In

1933 there were seven Jewish residents living in Aalen, two of whom

were children. During Kristallnacht in 1938, the shop windows of the

three Jewish shops in the town were shattered and the owners

subsequently imprisoned in the Dachau concentration camp for several

weeks. After their release, most of the Jews emigrated. Eduard and

Frieda Heilbron last lived in a so-called Judenhaus in Wiesbaden,

where Eduard Heilbronn died of a heart attack. His wife Frieda was

deported to Theresienstadt and later murdered in the Treblinka

extermination camp. Their daughter Irene survived, managing to emigrate

to Colombia with her husband Kurt Wartzki and their children. The last

Jewish resident, Fanny Kahn, was forcibly relocated to Oberdorf am Ipf in 1941, later deported and also murdered in. In 2005 a

street in Aalen was named in her honour. Of the town's Jews who were

murdered, Yad Vashem, records the names of Leopold Elter; Eduard, Frieda

and their son Willi Heilbronn; and Fanny Kahn. In

Aalen, there are sixteen stolpersteine memorials located at seven

different sites. One at Bahnhofstrasse 23 names Siegfried Pappenheimer

as one of those children saved by the British before the war through the

kindertransport in 1939. Another on Hofherrnstrasse 28 commemorates Karl Schiele, a member of the Communist Party who had taken part in

protests against the Nazis and was arrested on March 20, 1933 and taken

to one of the first concentration camps, the Heuberg camp. He was

imprisoned until April 11, 1933. After the war began, he listened to

foreign broadcasters; a sports teammate betrayed him under torture and

Schiele was arrested on March 6, 1940 at his workplace. The Stuttgart

Special Court sentenced him to twenty months in prison. His wife, who

had refused to testify against him, was imprisoned in Gotteszell for ten

months. He arrived at the notorious moor camp in the Emsland and was

released in June 1942 - seven months after the end of his sentence,

emaciated to the bone and with tuberculosis. The camp administration

dubbed him an 'unusable subject'. He did not recover and died after a

long illness on April 3, 1944 in the Isny sanatorium. After the war his

widow managed to have his sentence posthumously overturned and he was

officially recognised as one persecuted by the Nazi regime. She lived in

poverty in Dewangen and died in 1991.

In

Aalen, there are sixteen stolpersteine memorials located at seven

different sites. One at Bahnhofstrasse 23 names Siegfried Pappenheimer

as one of those children saved by the British before the war through the

kindertransport in 1939. Another on Hofherrnstrasse 28 commemorates Karl Schiele, a member of the Communist Party who had taken part in

protests against the Nazis and was arrested on March 20, 1933 and taken

to one of the first concentration camps, the Heuberg camp. He was

imprisoned until April 11, 1933. After the war began, he listened to

foreign broadcasters; a sports teammate betrayed him under torture and

Schiele was arrested on March 6, 1940 at his workplace. The Stuttgart

Special Court sentenced him to twenty months in prison. His wife, who

had refused to testify against him, was imprisoned in Gotteszell for ten

months. He arrived at the notorious moor camp in the Emsland and was

released in June 1942 - seven months after the end of his sentence,

emaciated to the bone and with tuberculosis. The camp administration

dubbed him an 'unusable subject'. He did not recover and died after a

long illness on April 3, 1944 in the Isny sanatorium. After the war his

widow managed to have his sentence posthumously overturned and he was

officially recognised as one persecuted by the Nazi regime. She lived in

poverty in Dewangen and died in 1991. In

August 1934, the Nazi consumer exhibition Braune Messe took place in

Aalen. This was primarily intended to serve as a platform for local

handicrafts to present themselves and their products. Similar events had

already been held in Nördlingen and Schwäbisch Gmünd during the year.

In 1936, a riding and driving school for the military was stationed in

the city, an army supplies office and an ancillary equipment office were

set up and housed an ancillary army ammunition facility. In 1935, the

incorporation of neighbouring towns began. In the town's hospital, the

deaconesses who had previously worked there were increasingly being

replaced by sisters of the National Socialist People's Welfare. At the

same time in the course of the Nazis' so-called racial hygiene

programme, around 200 people were forcibly sterilised there; three are recorded on the town's stolpersteine as having been murdered in the T-4 euthanasia programme.

In

September 1944, the Wiesendorf concentration camp, a satellite camp of

the Natzweiler/Alsace concentration camp, was set up in Wasseralfingen

for 200 to 300 prisoners who had to do forced labour in industrial

companies in the area. By the time the camp was closed in February 1945,

sixty prisoners had died. Between 1946 to 1957 the warehouse buildings

were demolished although I was able to still see its foundations still

in place on Moltkestrasse 44/46 as seen on the left. In addition,

prisoners of war as well as women and men from countries occupied by

Germany were concentrated in several labour camps who were forced to

work for the armaments industry in large companies such as the Swabian

ironworks and the Alfing Keßler machine factory.

In

September 1944, the Wiesendorf concentration camp, a satellite camp of

the Natzweiler/Alsace concentration camp, was set up in Wasseralfingen

for 200 to 300 prisoners who had to do forced labour in industrial

companies in the area. By the time the camp was closed in February 1945,

sixty prisoners had died. Between 1946 to 1957 the warehouse buildings

were demolished although I was able to still see its foundations still

in place on Moltkestrasse 44/46 as seen on the left. In addition,

prisoners of war as well as women and men from countries occupied by

Germany were concentrated in several labour camps who were forced to

work for the armaments industry in large companies such as the Swabian

ironworks and the Alfing Keßler machine factory.

In

September 1944, the Wiesendorf concentration camp, a satellite camp of

the Natzweiler/Alsace concentration camp, was set up in Wasseralfingen

for 200 to 300 prisoners who had to do forced labour in industrial

companies in the area. By the time the camp was closed in February 1945,

sixty prisoners had died. Between 1946 to 1957 the warehouse buildings

were demolished although I was able to still see its foundations still

in place on Moltkestrasse 44/46 as seen on the left. In addition,

prisoners of war as well as women and men from countries occupied by

Germany were concentrated in several labour camps who were forced to

work for the armaments industry in large companies such as the Swabian

ironworks and the Alfing Keßler machine factory.

In

September 1944, the Wiesendorf concentration camp, a satellite camp of

the Natzweiler/Alsace concentration camp, was set up in Wasseralfingen

for 200 to 300 prisoners who had to do forced labour in industrial

companies in the area. By the time the camp was closed in February 1945,

sixty prisoners had died. Between 1946 to 1957 the warehouse buildings

were demolished although I was able to still see its foundations still

in place on Moltkestrasse 44/46 as seen on the left. In addition,

prisoners of war as well as women and men from countries occupied by

Germany were concentrated in several labour camps who were forced to

work for the armaments industry in large companies such as the Swabian

ironworks and the Alfing Keßler machine factory.  A flag-bedecked Adolf-Hitler-Platz (now Bahnhofplatz) showing a red swastika-adorned railway station on May Day 1939. In

general, Aalen was largely spared from the war although the station

would not survive unscathed. It was not until the last weeks of the war

that air strikes led to the destruction or serious damage to parts of

the city, the train station and the other railway facilities. On April

1, Easter Sunday, Aalen experienced one of the heaviest air raids of the war when American fighter-bombers first attacked targets in the

city. This began a series of air strikes that lasted more than three

weeks which culminated on April 17, 1945, when American Air Force

bombers bombed the auxiliary armoury stationed in Aalen and the railroad

facilities. 59 people were killed, over half of them were buried, and

more than 500 left homeless. 45 buildings, 33 of which were residential, and

two bridges were destroyed and 163 buildings, including a couple of

churches, were also damaged. Five days later, the Nazi regime in Aalen

was deposed by the American armed forces.

A flag-bedecked Adolf-Hitler-Platz (now Bahnhofplatz) showing a red swastika-adorned railway station on May Day 1939. In

general, Aalen was largely spared from the war although the station

would not survive unscathed. It was not until the last weeks of the war

that air strikes led to the destruction or serious damage to parts of

the city, the train station and the other railway facilities. On April

1, Easter Sunday, Aalen experienced one of the heaviest air raids of the war when American fighter-bombers first attacked targets in the

city. This began a series of air strikes that lasted more than three

weeks which culminated on April 17, 1945, when American Air Force

bombers bombed the auxiliary armoury stationed in Aalen and the railroad

facilities. 59 people were killed, over half of them were buried, and

more than 500 left homeless. 45 buildings, 33 of which were residential, and

two bridges were destroyed and 163 buildings, including a couple of

churches, were also damaged. Five days later, the Nazi regime in Aalen

was deposed by the American armed forces. What particularly drove me to visit Aalen was the Limesmuseum,

located on the site of the largest Roman equestrian fort north of the

Alps. The size of the fort indicates that it was garrisoned by the ala II Flavia milliaria, the only ala milliaria of the province. Indeed, the elite mounted unit, the ala miliaria,

is what gives Aalen its name. In May 2019, after two and a half years

of renovation and closure, it was reopened with a newly designed

permanent exhibition with over 1,200 original finds. The main focus is

on the relationship between Teutons and Romans and the understanding of

borders. In the main rooms on the ground floor, visitors are forced to

interactively learn about seven people who lived in Roman Aalen 1,800

years ago using specific archaeological objects and get to know their

living conditions better. For me, this completely ruined the experience

as one can't walk anywhere or view some of the spectacular pieces in

peace- such as the masked cavalry helmet found during the expansion of

the Limes Museum and the huge Osterburken Mithras relief- without

setting off a cacophony of sound effects- horses, for example- and loud

voice overs that could not be shut off.

What particularly drove me to visit Aalen was the Limesmuseum,

located on the site of the largest Roman equestrian fort north of the

Alps. The size of the fort indicates that it was garrisoned by the ala II Flavia milliaria, the only ala milliaria of the province. Indeed, the elite mounted unit, the ala miliaria,

is what gives Aalen its name. In May 2019, after two and a half years

of renovation and closure, it was reopened with a newly designed

permanent exhibition with over 1,200 original finds. The main focus is

on the relationship between Teutons and Romans and the understanding of

borders. In the main rooms on the ground floor, visitors are forced to

interactively learn about seven people who lived in Roman Aalen 1,800

years ago using specific archaeological objects and get to know their

living conditions better. For me, this completely ruined the experience

as one can't walk anywhere or view some of the spectacular pieces in

peace- such as the masked cavalry helmet found during the expansion of

the Limes Museum and the huge Osterburken Mithras relief- without

setting off a cacophony of sound effects- horses, for example- and loud

voice overs that could not be shut off.

At

the staff building, the principia, with a modern statue of Hadrian

despite the fort being built during the 160s as part of the military

reorganisation and expansion of Marcus Aurelius; the dendrochronological

records fall in the period between 159 and 172. An impressive number of

sixteen building inscriptions have been found from Aalen, all datable

to the Severan dynasty. The fort was operational until the middle of the

3rd century and evidence from coins indicates that the fort was

destroyed following the reign of Aemilian, in the years after 253-254,

although there have been two disputable coins issued under Emperors Valerian and Gallienus that have also been found.

Part

of the Roman fort has been incorporated in the town cemetery in which

is located St. Johann's Church, one of Aalen's oldest buildings, dating

back to the 13th century. Located directly in front of the former porta praetoria, the main gate of a Roman camp, the Roman stone

blocks which were reused at the time to build it can be clearly seen in

the area of the foundation. The excavation in 1997 whose preserved

remains are shown here and from the same spot today offer valuable insights

into the history of Aalen in the early Middle Ages. For example, it was

discovered that the church was not the oldest building in this

location. The articles found date back to the seventh and eighth

centuries. It appears that around this time, directly on the road in

front of the former main gate of the garrison, a residential building or

an early monastery cell was located here. The oldest parts of the

buildings 1 and 2 belong to this era as well as a number of graves

nearby which were excavated at the start of the 20th century. The

present-day church itself was built sometime around the twelfth and

thirteenth centuries. Work was carried out on Building 2 at the same

time, also using stones from the fortress as building material. On the

western corner there was a Roman inscription to the goddess Minerva

which is now in the Limes Museum.

Part

of the Roman fort has been incorporated in the town cemetery in which

is located St. Johann's Church, one of Aalen's oldest buildings, dating

back to the 13th century. Located directly in front of the former porta praetoria, the main gate of a Roman camp, the Roman stone

blocks which were reused at the time to build it can be clearly seen in

the area of the foundation. The excavation in 1997 whose preserved

remains are shown here and from the same spot today offer valuable insights

into the history of Aalen in the early Middle Ages. For example, it was

discovered that the church was not the oldest building in this

location. The articles found date back to the seventh and eighth

centuries. It appears that around this time, directly on the road in

front of the former main gate of the garrison, a residential building or

an early monastery cell was located here. The oldest parts of the

buildings 1 and 2 belong to this era as well as a number of graves

nearby which were excavated at the start of the 20th century. The

present-day church itself was built sometime around the twelfth and

thirteenth centuries. Work was carried out on Building 2 at the same

time, also using stones from the fortress as building material. On the

western corner there was a Roman inscription to the goddess Minerva

which is now in the Limes Museum.

Schloss Sigmaringen

Following

the Anglo-American liberation of France, the French Regime was moved from

France into Schloss Sigmaringen. The princely family was forced by the

Gestapo out of the castle and moved to Schloss Wilflingen. The French

authors Louis-Ferdinand Céline and Lucien Rebatet, who had written

political and anti-semitic works, fled to

Sigmaringen with the Vichy government. Céline's 1957 novel D'un château

l'autre, describes the end of the war and the fall of Sigmaringen on April 22, 1945 and was made into a German movie in 2006, called Die Finsternis. Relocated to

Sigmaringen in the summer of 1944, the Vichy government no

longer had any relevance. On September 7, fleeing the advance of the Allied troops in France whilst

Germany was in flames and the Vichy regime no longer existed, a

thousand French collaborators (including an hundred officials, a few

hundred members of the French militia and militants of the

collaborationist parties and the editorial staff of the journal Je suis partout), came here. Pétain and Laval were led away according to what they said had been

"against their will" by the Germans in their retreat in August 1944 and

resided there until April 1945. The government commission, chaired by

Fernand de Brinon and supposed to incarnate the continuity of the

Vichy regime, was formed, composed of former members of the Vichy

governments, but some who followed Petain to Sigmaringen refused to

participate. Visitors were

even obliged to present a piece of identification, since they were

entering French territory. This "Sigmaringen government" lasted until

April 1945. Petain, his suite, and his ministers, though on "strike," lodged in the castle whilst the rest were housed in schools and gymnasiums, transformed into dormitories, and in the few guest rooms and

hotels in the city, such as the Bären or Löwen, which received the most

prestigious guests, including the writer Louis-Ferdinand Céline in the

book D'un château l'autre. The exiles in the city's shanty houses were

hardly able to live in summer, but especially in the winter under the

rumbling of Anglo-American bombs and an intense cold which reached -30°C

in December 1944. On the approach of the Allies in April 1945, most of

them

exiled themselves: Petain was taken by the Germans in a fashion to the

Swiss border, Laval fled to Spain, Brinon took refuge in the

surroundings of Innsbruck, whilst others found refuge in Northern Italy.

Following

the Anglo-American liberation of France, the French Regime was moved from

France into Schloss Sigmaringen. The princely family was forced by the

Gestapo out of the castle and moved to Schloss Wilflingen. The French

authors Louis-Ferdinand Céline and Lucien Rebatet, who had written

political and anti-semitic works, fled to

Sigmaringen with the Vichy government. Céline's 1957 novel D'un château

l'autre, describes the end of the war and the fall of Sigmaringen on April 22, 1945 and was made into a German movie in 2006, called Die Finsternis. Relocated to

Sigmaringen in the summer of 1944, the Vichy government no

longer had any relevance. On September 7, fleeing the advance of the Allied troops in France whilst

Germany was in flames and the Vichy regime no longer existed, a

thousand French collaborators (including an hundred officials, a few

hundred members of the French militia and militants of the

collaborationist parties and the editorial staff of the journal Je suis partout), came here. Pétain and Laval were led away according to what they said had been

"against their will" by the Germans in their retreat in August 1944 and

resided there until April 1945. The government commission, chaired by

Fernand de Brinon and supposed to incarnate the continuity of the

Vichy regime, was formed, composed of former members of the Vichy

governments, but some who followed Petain to Sigmaringen refused to

participate. Visitors were

even obliged to present a piece of identification, since they were

entering French territory. This "Sigmaringen government" lasted until

April 1945. Petain, his suite, and his ministers, though on "strike," lodged in the castle whilst the rest were housed in schools and gymnasiums, transformed into dormitories, and in the few guest rooms and

hotels in the city, such as the Bären or Löwen, which received the most

prestigious guests, including the writer Louis-Ferdinand Céline in the

book D'un château l'autre. The exiles in the city's shanty houses were

hardly able to live in summer, but especially in the winter under the

rumbling of Anglo-American bombs and an intense cold which reached -30°C

in December 1944. On the approach of the Allies in April 1945, most of

them

exiled themselves: Petain was taken by the Germans in a fashion to the

Swiss border, Laval fled to Spain, Brinon took refuge in the

surroundings of Innsbruck, whilst others found refuge in Northern Italy.

Postwar, some 10,000 French were executed for collaboration with the Germans, including Laval. Pétain, stripped of his rank, was condemned to death, but de Gaulle commuted the sentence to life in prison. Despite de Gaulle’s ridiculous efforts to cast France during the war as a nation of resisters, the four-year-long Vichy regime left a legacy of that still shames France today.

Following

the Anglo-American liberation of France, the French Regime was moved from

France into Schloss Sigmaringen. The princely family was forced by the

Gestapo out of the castle and moved to Schloss Wilflingen. The French

authors Louis-Ferdinand Céline and Lucien Rebatet, who had written

political and anti-semitic works, fled to

Sigmaringen with the Vichy government. Céline's 1957 novel D'un château

l'autre, describes the end of the war and the fall of Sigmaringen on April 22, 1945 and was made into a German movie in 2006, called Die Finsternis. Relocated to

Sigmaringen in the summer of 1944, the Vichy government no

longer had any relevance. On September 7, fleeing the advance of the Allied troops in France whilst

Germany was in flames and the Vichy regime no longer existed, a

thousand French collaborators (including an hundred officials, a few

hundred members of the French militia and militants of the

collaborationist parties and the editorial staff of the journal Je suis partout), came here. Pétain and Laval were led away according to what they said had been

"against their will" by the Germans in their retreat in August 1944 and

resided there until April 1945. The government commission, chaired by

Fernand de Brinon and supposed to incarnate the continuity of the

Vichy regime, was formed, composed of former members of the Vichy

governments, but some who followed Petain to Sigmaringen refused to

participate. Visitors were

even obliged to present a piece of identification, since they were

entering French territory. This "Sigmaringen government" lasted until

April 1945. Petain, his suite, and his ministers, though on "strike," lodged in the castle whilst the rest were housed in schools and gymnasiums, transformed into dormitories, and in the few guest rooms and

hotels in the city, such as the Bären or Löwen, which received the most

prestigious guests, including the writer Louis-Ferdinand Céline in the

book D'un château l'autre. The exiles in the city's shanty houses were

hardly able to live in summer, but especially in the winter under the

rumbling of Anglo-American bombs and an intense cold which reached -30°C

in December 1944. On the approach of the Allies in April 1945, most of

them

exiled themselves: Petain was taken by the Germans in a fashion to the

Swiss border, Laval fled to Spain, Brinon took refuge in the

surroundings of Innsbruck, whilst others found refuge in Northern Italy.

Following

the Anglo-American liberation of France, the French Regime was moved from

France into Schloss Sigmaringen. The princely family was forced by the

Gestapo out of the castle and moved to Schloss Wilflingen. The French

authors Louis-Ferdinand Céline and Lucien Rebatet, who had written

political and anti-semitic works, fled to

Sigmaringen with the Vichy government. Céline's 1957 novel D'un château

l'autre, describes the end of the war and the fall of Sigmaringen on April 22, 1945 and was made into a German movie in 2006, called Die Finsternis. Relocated to

Sigmaringen in the summer of 1944, the Vichy government no

longer had any relevance. On September 7, fleeing the advance of the Allied troops in France whilst

Germany was in flames and the Vichy regime no longer existed, a

thousand French collaborators (including an hundred officials, a few

hundred members of the French militia and militants of the

collaborationist parties and the editorial staff of the journal Je suis partout), came here. Pétain and Laval were led away according to what they said had been

"against their will" by the Germans in their retreat in August 1944 and

resided there until April 1945. The government commission, chaired by

Fernand de Brinon and supposed to incarnate the continuity of the

Vichy regime, was formed, composed of former members of the Vichy

governments, but some who followed Petain to Sigmaringen refused to

participate. Visitors were

even obliged to present a piece of identification, since they were

entering French territory. This "Sigmaringen government" lasted until

April 1945. Petain, his suite, and his ministers, though on "strike," lodged in the castle whilst the rest were housed in schools and gymnasiums, transformed into dormitories, and in the few guest rooms and

hotels in the city, such as the Bären or Löwen, which received the most

prestigious guests, including the writer Louis-Ferdinand Céline in the

book D'un château l'autre. The exiles in the city's shanty houses were

hardly able to live in summer, but especially in the winter under the

rumbling of Anglo-American bombs and an intense cold which reached -30°C

in December 1944. On the approach of the Allies in April 1945, most of

them

exiled themselves: Petain was taken by the Germans in a fashion to the

Swiss border, Laval fled to Spain, Brinon took refuge in the

surroundings of Innsbruck, whilst others found refuge in Northern Italy.Postwar, some 10,000 French were executed for collaboration with the Germans, including Laval. Pétain, stripped of his rank, was condemned to death, but de Gaulle commuted the sentence to life in prison. Despite de Gaulle’s ridiculous efforts to cast France during the war as a nation of resisters, the four-year-long Vichy regime left a legacy of that still shames France today.

Ravensburg

Irving

in Goebbels: Mastermind of the Third Reich (30) writes how Goebbels played "the huge cathedral organ" in the cathedral shown in the

background in 1918 for two other students he had travelled the area

with. During the war, Ravensburg was strategically of no relevance.

Ravensburg did not harbour any noteworthy arms industry (unlike nearby

Friedrichshafen with its large aircraft industry), but was home to a big

aid supplies centre belonging to the Swiss Red Cross; so no air raid

destroyed the historic city centre. During

the Nazi era 691 patients from the Weißenau psychiatric clinic were

murdered as victims of "euthanasia." The Sinti resident in the city were

first interned in the Gypsy Forced Labour Camp, thirty-six Sinti were

deported in 1943 with 29 of them murdered in Auschwitz. The few Jews who

had settled in Ravensburg had been forced to flee with some murdered as

victims of the Holocaust.

The town hall then and now, with Nazi functionaries in front of the entrance in 1938 and today

Nazis

intimidating those thinking of shopping at the Jewish-owned Kaufhaus

Landauer, and stolperstein at the site today, remembering the murdered

Landauers.

Böblingen

Flughafen

Böblingen. On April 9, 1932 Hitler spoke at this airport that was later

used by the USAAF after the war. Some buildings remain; on the right below is

the reception building dating from 1925. During the Great War, the Böblingen military airfield was inaugurated on August

16, 1915. Subsequently, it was of decisive importance for the further

development of the town that Böblingen became the seat of the

Landesflughafen for Württemberg in 1925 making Böblingen the "Brücke zur

Welt" (bridge to the world).

At the end of the airfield, Böschinger aviation pioneer Hanns Klemm set

up his company "Leichtflugzeugbau Klemm" at the end of 1926. Until the

war, this became the most important industrial city in the region. The

Gleichschaltung of Böblingen began within weeks of Hitler’s appointment

as Chancellor. On March 9, 1933, the Böblingen town council was

forcibly dissolved, and Mayor Wilhelm Schuster, a member of the Centre

Party, was compelled to resign. Nazi Party Kreisleiter Eugen Ostertag

installed Fritz Seeger, a party loyalist, as acting mayor. The municipal

council minutes from March and April 1933, held in the Stadtarchiv

Böblingen, record the purge of Social Democratic and Communist

councillors and their replacement by National Socialist members. The Law

for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service was implemented

locally in May 1933, leading to the dismissal of Jewish and “politically

unreliable” teachers and civil servants. The staff list of the

Böblingen Oberrealschule for 1933–34 shows the removal of three

teachers—including Ernst Weil, dismissed for his Jewish ancestry—and the

replacement of the school’s headmaster with party member Wilhelm Beck.

The DAF replaced all free unions, and the local chapter of the Hitler

Youth, established in 1932, became compulsory for all schoolboys by

1936, as noted in the school’s annual reports.

The

Nazi regime’s policies of anti-Semitic persecution and racial exclusion

were rigorously enforced in Böblingen. At the time of the Nazi

takeover, the Jewish community in Böblingen numbered fewer than 30,

primarily merchants and professionals. The 1935 population register

lists the families of Julius Wertheimer, Albert Haas, and Emma

Löwenstein as resident in the town. The Nuremberg Laws were enforced

locally, with the town council refusing to renew business licenses for

Jewish shopkeepers and banning Jewish children from public schools by

1936. On 10 November 1938, during the Kristallnacht pogrom, the

Böblingen synagogue on Poststraße was attacked and set on fire by SA

members under the command of Willi Stör. The police report for that

night, preserved in the Landesarchiv Baden-Württemberg, records the

looting of Jewish homes and shops, the arrest of Julius Wertheimer and

Werner Löwenstein, and their deportation to Dachau. The synagogue site

was subsequently cleared, and by April 1939, no Jewish families remained

in Böblingen. The fate of those arrested is documented in later

deportation lists: Wertheimer perished in Gurs camp in 1941, while

Löwenstein was murdered in Auschwitz in 1942. The Sinti and Roma

population of Böblingen, present since the late 19th century, was also

targeted. The police register of 1939 lists seventeen Sinti residents, most of

whom were detained under the regime’s anti-“Gypsy” laws. In May 1940,

the Böblingen Sinti were rounded up, held in the town jail, and sent to

the Hohenasperg transit camp before deportation to Auschwitz. Only two

survivors are known to have returned after 1945. The Law for the

Prevention of Hereditarily Diseased Offspring was enforced by the town’s

health office, resulting in the forced sterilisation of at least 19

residents between 1934 and 1941, according to the records of the

Böblingen district hospital. Böblingen’s economy and infrastructure

were rapidly integrated into the Nazi war effort. The town’s population,

which stood at 8,123 in 1933, grew to over 13,000 by 1944, largely due

to industrial expansion and the influx of forced labourers. The

Motorenwerke Böblingen (MBB), established in 1937 on the site of the

former airfield, became a key supplier of engines and aircraft parts for

the Luftwaffe. The factory’s personnel records, now in the Stadtarchiv,

show the recruitment of hundreds of workers from occupied countries,

particularly France, the Soviet Union, and Poland, beginning in 1942. By

1944, Böblingen counted more than 1,100 foreign forced labourers, who

were housed in barracks on Sindelfinger Straße and subjected to harsh

conditions, as confirmed by the “Fremdarbeiterkartei” (foreign worker

register) and reports of the local police. The town’s railway station

became a crucial hub for military logistics, with the council minutes of

1940 noting the construction of new sidings and warehouses at the

request of the Wehrmacht.

The St. Dionysius church in 1943 and today. The war had direct and devastating

consequences for Böblingen’s civilian population. The first air raid

warning was recorded on May 23, 1940; the town’s air raid shelter

construction programme expanded in 1942, with the building of bunkers

under the market square and at the MBB factory. On

the night of October 7, 1943, Böblingen suffered its first major air

raid when RAF bombers targeted the railway and industrial area. The

police casualty report lists 22 killed and 41 injured, with over seventy

buildings destroyed or damaged. Through this and other

bombings, about 40% of the built-up area had been destroyed

during warfare and nearly 2,000 people were homeless.The

most destructive attack occurred on 7 January 1945, when a USAAF raid

destroyed the railway station, severely damaged the MBB factory, and

left 86 civilians dead. The municipal chronicle records the use of

schools and churches as makeshift hospitals and the burial of victims in

mass graves at the Waldfriedhof. The collapse of the Nazi regime in

Böblingen unfolded rapidly in April 1945. As Allied troops advanced from

Stuttgart, Mayor Fritz Seeger and senior Nazi Party officials fled the

town on 19 April. The post-war years in Böblingen were marked by the

arrival of refugees from Silesia and the Sudetenland, the slow

reconstruction of the devastated town centre, and the gradual process of

confronting the Nazi past. In 1951, the town council approved the

erection of a memorial stone for the Jewish victims on the site of the

former synagogue. Further archival research in the 1980s and 1990s, led

by the Böblingen Historical Society, resulted in the publication of

lists of Jewish, Sinti, and forced labour victims, and the installation

of plaques at key sites, including the Waldfriedhof and the former MBB

factory.

Hardheim

The schlossplatz in front of what is now the Erfatal-Museum

Freistett

The

memorial to the Franco-Prussian War remains between the town hall and

the church. Freistett, as a local administrative centre in the

Hanauerland region near the Rhine in Baden, experienced the direct

imposition of Nazi rule after the national seizure of power in 1933. The

earliest evidence of Gleichschaltung in Freistett appears in town

council records from March and April 1933, which document the forced

resignation of Bürgermeister Wilhelm Wörner, who was replaced by Nazi

Party member Karl Doll on April 7, 1933. The council minutes from

April 17, 1933 record the removal of two members with suspected Social

Democratic leanings, replaced by party loyalists. The town’s school

head, Ludwig Hummel, was required to sign a declaration of loyalty to

Hitler on May 20, 1933, as listed in the Freistett school chronicle. By

September 1933, the Freistett volunteer fire brigade had been

incorporated into the national fire service and subjected to Nazi

discipline, as shown in the brigade’s annual report. The local chapter

of the Deutscher Reichsbund für Leibesübungen (DRL) was established in

1934 and quickly absorbed the Freistetter Turnverein, documented in the

Turnverein’s 1934 meeting minutes.The former site of the town's Jewish cemetery; the last burial had been of Gustav Bloch from nearby Rheinbischofsheim in 1939. Due to declining membership, the Jewish communities in Freistett and Rheinbischofsheim were combined in June 1935 and the synagogue attended Freistetter Jews was henceforth in Rheinbischofsheim. The 1935 town tax register lists Isaak Stern, a livestock trader, as the only Jewish taxpayer. On November 10, 1938, the day after Kristallnacht, the local SA unit, led by Hermann Bühler, broke into Stern’s home on Kirchstraße, looted his possessions, and forced him to sign over his remaining property to the town. The town’s police log from that day notes the arrest of Stern and his transfer to the Rastatt prison, from which he was subsequently deported to Dachau. No synagogues existed in Freistett, but the Jewish cemetery, located near the Schaidtweg road, was desecrated during the same period, with headstones smashed and Hebrew inscriptions defaced. The municipal records for 1939 confirm that the last Jewish family, the Sterns, were removed from the official residence rolls in June of that year. The synagogue in Rheinbischofsheim was finally demolished in 1953.

Political

repression in Freistett is documented through Gestapo records preserved

in the Karlsruhe State Archives. A report dated January 12, 1934

details the arrest of the carpenter Eugen Ernst, accused of distributing

anti-Nazi pamphlets. Ernst was held in the Offenburg jail for two weeks

before being released under police supervision. Another report from 9

June 1937 records the interrogation of parish priest Pater Josef Ruf,

following a sermon critical of the regime’s treatment of Catholic youth

groups. The Freistett parish newsletter of July 1937 makes veiled

reference to “the increasing demands of the authorities on the

consciences of believers,” an allusion to Nazi interference in church

affairs.

Schloß Kapfenburg

During the time the castle served as a Gauschule, which was a training centre for local government employees, in this case for the NSV (NS-Volkswohlfahrt,

the Nazi welfare organisation). At the outbreak of the war, the NSV,

with around 15 million members, was the second largest Nazi organisation

after the Deutschen Arbeitsfront (DAF). Around one million volunteers

and around 30,000 full-time officials were involved in the Nazi welfare

organisation. During the war, the NSV provided initial care to those

bombed out and the homeless, and organised evacuations after air raids .

These activities in particular contributed to the population's

continued loyalty to the Nazi regime until the end of the war. The NSV

established joint emergency service centers in individual districts to

care for victims of the air war, thereby increasing the efficiency of

the measures. However, this consensual cooperation also fueled the

segregation of society into 'valuable' and 'inferior' people when

welfare applications were no longer decided objectively based on need,

but rather on ideological criteria.

Waldhilsbach

The Gasthaus zum Röss'l sporting

the Nazi flag during the war and today. It's still in operation on

Heidelberger Straße 15 with its thirteen rooms. Waldhilsbach was,

already before war, a commuter community, as the agricultural land of

the district and the forest work in the Heidelberg city forest did not

provide a sufficient agricultural livelihood. This development continued

after the war, when the community received around 200

refugees, many of whom settled here. Since the end of the 1950s,

agriculture no longer had any economic significance. The economic

development was hampered by the unfavourable traffic conditions and the

cramped conditions in the district but given its location on the

southeastern slope of Königstuhlscholle on the southern edge of the

Buntsandsteinodenwald, surrounded by idyllic fields and meadows with

numerous fruit trees, it's become a notable tourist hub.

The Gasthaus zum Röss'l sporting

the Nazi flag during the war and today. It's still in operation on

Heidelberger Straße 15 with its thirteen rooms. Waldhilsbach was,

already before war, a commuter community, as the agricultural land of

the district and the forest work in the Heidelberg city forest did not

provide a sufficient agricultural livelihood. This development continued

after the war, when the community received around 200

refugees, many of whom settled here. Since the end of the 1950s,

agriculture no longer had any economic significance. The economic

development was hampered by the unfavourable traffic conditions and the

cramped conditions in the district but given its location on the

southeastern slope of Königstuhlscholle on the southern edge of the

Buntsandsteinodenwald, surrounded by idyllic fields and meadows with

numerous fruit trees, it's become a notable tourist hub.

Bräunlingen

The stadttor on the former Robert Wagner Straße, named after the

Gauleiter of Baden. The SA was established in Bräunlingen in 1931.

During the Nazi era the Jewish-owned Kaufhaus Zimmt on Blaumeerstraße 13

was increasingly boycotted. To keep some customers, Fritz Zimmt

hanged up a sign reading "Entrance also from behind". On the street in

front of the Zimmt department store was scrawled 'The Jews are our

misfortune'. A few younger workers of the Ortsgruppenleiter attacked Zimmt in the Hasenfratz

hairdressing salon leaving him beaten with his teeth knocked out. The

local newspaper would report how the shop, "which was temporarily owned

by the Jews, has now received another Aryan successor." Zimmt fled,

before which he had hoped to entrust his dog to the neighbours, going so

far as paying the dog tax two years in advance only to have his dog

eventually shot. On February 18, 1939, he and his family first travelled

to Genoa, then by ship to Shanghai. Fritz Zimmt died in 1945.

The stadttor on the former Robert Wagner Straße, named after the

Gauleiter of Baden. The SA was established in Bräunlingen in 1931.

During the Nazi era the Jewish-owned Kaufhaus Zimmt on Blaumeerstraße 13

was increasingly boycotted. To keep some customers, Fritz Zimmt

hanged up a sign reading "Entrance also from behind". On the street in

front of the Zimmt department store was scrawled 'The Jews are our

misfortune'. A few younger workers of the Ortsgruppenleiter attacked Zimmt in the Hasenfratz

hairdressing salon leaving him beaten with his teeth knocked out. The

local newspaper would report how the shop, "which was temporarily owned

by the Jews, has now received another Aryan successor." Zimmt fled,

before which he had hoped to entrust his dog to the neighbours, going so

far as paying the dog tax two years in advance only to have his dog

eventually shot. On February 18, 1939, he and his family first travelled

to Genoa, then by ship to Shanghai. Fritz Zimmt died in 1945.

In

July 1940 Robert Wagner, now in charge of Alsace, and Josef Bürckel,

Gauleiter of the Saar-Palatinate and Chief of the Civil Administration

in Lorraine, both pressed Hitler to allow the expulsion westwards into

Vichy France of the Jews from their domains. Hitler gave his approval.

Some 3,000 Jews were deported that month from Alsace into the unoccupied

zone of France. In October, following a further meeting with the two

Gauleiter, a total of 6,504 Jews were sent to France in nine trainloads,

without any prior consultation with the French authorities, who

appeared to have in mind their further deportation to Madagascar as soon

as the sea-passage was secure.

Lörrach

Café Binoth, now the Drei König, on the former Adolf Hitler Straße. Early during the period of

the Weimar Republic, there was growing social unrest in Lörrach

starting on the 14th of September, 1923 which left three dead, many

injured, and several examples of hostage abuse. The economic slump also

led to the authorities and the administration being unable to carry out

urgent construction projects. It was around this time the Nazis grew in

support. The Nazi Party in Lörrach had existed since 1922. However,

during the 1920s the Weimar Republic was rather difficult to gain a

foothold, although there was also anti-parliamentary propaganda in

Lörrach with the German nationalist journal Der Markgräfler run

by Hermann Burte. After the Nazi seizure of power, Reinhard Boos was

appointed mayor of Lörrach in 1933. Boos, who built and strengthened the

Nazi party in Lörrach with great enthusiasm, subsequently taking part in the

defeat of the trade unions and the opposition parties. From 1938

onwards, Boos played a leading role in the actions against the Lörrach

Jews. During the November pogroms of 1938 several men gained access to

the synagogue and destroyed them. The destroyed Gotteshaus was then

demolished. Lorrach remained comparatively undamaged during the Second

World war thanks to the geographical distance to the fronts. On April

24, 1945, French troops occupied Lörrach, adding to its humiliation.

Amstetten

Amstetten

|

| Adolf Hitlerplatz and today |

Nagold

The

Hotel Post on Adolf Hitler Straße and today. Nagold was the home of

Emilie Christine (Christa) Schroeder, one of Adolf Hitler’s personal

secretaries before and during the war. Schroeder would

argue that she was never a Nazi but simply worked with Hitler. In 1945,

she was originally considered to be a war criminal but was later

reclassified as a collaborator and released days later, on May 12, 1948.

As early as 1924, Nagold was a Nazi base of support in which, according

to voting statistics, 19.4% of the population voted for the Nazis that

May. Comparatively, the Nazis captured just 6.5% of the vote nationwide,

and a mere 4.1% in Baden and Württemberg during the same election.

After the war, the town had the shame of falling within the French

occupation zone until 1947. Right-wing parties in Nagold have been

successful in the postwar period. In the state election in 1968 , the

candidate of the NPD was elected by the second count in the state

legislature. The NPD is possibly the party most aligned to the Nazis

today, and according to the Federal Constitutional Protection Report of

2012, the objectives of the NPD are "incompatible" with the democratic

and constitutional characteristics of the Basic Law due to their "anti-

pluralistic, exclusionary and anti-egalitarian characteristics." The

ideological positions of the party are "expressing a closed right-wing

extremist worldview." In addition, the candidate of the REP succeeded in

1992 and 1996 to collect on the second count in the state legislature.

Since 2007 however, the party is no longer listed in the constitution

protection report as being a right-wing extremist party.

Gengenbach

Adolf-Hitler-Straße

in a Nazi-era postcard with the 13th century Obertorturm in the

background, and from the same site today. Eduard Mack had served as the

town's mayor from 1921–1933 when he was removed from office upon the Nazi seizure of power. According to the local newspaper Der Kinzigtäler from June 27 of that year

Mack had been taken into protective custody in the Offenburg gaol for

"inflammatory speeches against the NSDAP." He was replaced by Franz Geiger, a master tin maker and local group leader of the Gengenbach branch of the Nazi Party. He in turn was replaced by Nazi member Anton Hägele during the whole duration of the war.

Bad Cannstatt

The Rosensteinbunker outside Stuttgart then and now. The town saw, as

with towns across Germany, egregious violence towards its Jewish

population. On January 28, 1936, the Stuttgart district court sentenced

the Jewish insurance official Edwin Spiro from Taubenheimstrasse 60/2 to

six months in prison after being charged with violating the "Law for

the Protection of German Blood and Honour", which stipulated in §2:

"Extramarital traffic between Jews and nationals of German or related

blood is prohibited." After the pogrom night in 1938, he was arrested

again with tens of thousands of other Jews and incarcerated in the

dreaded Welzheim concentration camp until January 31, 1939. The

synagogue in Cannstatt was set on fire by the head of the fire station,

two firefighters and some Nazis during Reichskristalnacht. On that night

of November 9, 1938, Ida Carlebach from Dürrheimer Straße 5 and her

eleven-year-old neighbour Margarete Carle witnessed the fire at the

Cannstatt synagogue. Margarete Carle reported that her father came to

the children's room with the call "Children are on fire!" From where

they were, the flaming synagogue on König-Karl-Straße was easy to

observe. In fact, the sparks flew almost towards the house. With the

synagogue's destruction, Ida Carlebach committed suicide on November 27,

1938 and her house became 'aryanised' in March 1939.

The Rosensteinbunker outside Stuttgart then and now. The town saw, as

with towns across Germany, egregious violence towards its Jewish

population. On January 28, 1936, the Stuttgart district court sentenced