Abstract

The role of the Chinese Labour Corps is a topic curiously neglected in history, both in terms of its aid to the Allied powers as well as its impact on China. Rather than offering an analysis of their role in the Great War and their relationship with the West, this essay will concentrate on the role the Chinese Labour Corps played in China’s struggle to find foothold on the international stage. This results in the question “How significant was the Chinese Labour Corps in the formation of China’s New National Identity leading up to the May Fourth Movement?” The investigation is structured in the following manner: first giving an introduction to China’s political situation and the background of the Chinese Labour Corps so as to set the question in context and provide information that is vital in the understanding of the circumstances. Secondly, the opposing motives of China and the Allies are illustrated, followed by the role of education in Europe and the impact of returning scholars and workers in China. Finally, the conclusion to the question is approached and described. A variety of sources are used, offering both Western and Chinese viewpoints from contemporary and modern times. Notably, Chinese historian Xu Guoqi’s Strangers on the Western Front prominently features, being the first and only comprehensive study into the Chinese Labour Corp’s impact on China itself. Additionally, given that most were illiterate peasants, there is a scarcity of primary sources from the labourers, while any work they may have produced in later years does not seem to have been recorded.

Introduction

Western historians generally agree that China’s participation in the First World War was, for the most, insignificant. Chinese contribution as an Allied Power was not of value to the Allies, having joined the war in its later years and lacking military impact. What is often overlooked, however, is the role of the Chinese Labour Corps (CLC), and its involvement in shaping China’s national identity. Significantly, the May Fourth movement marked a fundamental turning point in history, in which a country previously set on Westernisation made a decisive turn against the West and towards Communism. While the cause of this decision is largely agreed to have been their betrayal at Versailles, one cannot understand the impact this duplicity had on the people and government, without understanding the changing national sentiment that was spreading in China, fuelled by the hope put into the CLC. Hence, this leads to the question “How significant was the Chinese Labour Corps in the formation of China’s new National Identity leading up to the May Fourth Movement?”

The impact of the CLC is still significant today – in a time where Chinese labourers are becoming increasingly undermined despite their importance in bringing the Communist party to power, their role in merging societal divides and making the first step towards internationalisation should not be overlooked. Moreover, the study of this seemingly obscure chapter in history is vital to understand the Chinese sentiment that was to shape the coming world order.

China’s Political Situation after the 1911 Revolution

The fall of the Qing dynasty after the 1911 Chinese Revolution marked an end to China’s time as an “embalmed mummy”, an imperial state with an unchanging society. The country witnessed an influx of ideas that were to shape their political motives during World War I. The Republic of China was founded, and, by 1912, Yuan Shikai ruled as president, later crowning himself emperor.

Having effectively established a dictatorship, his death in 1916 left a political vacuum that left the Beijing government in a purely symbolic role, while the true power was seized by warlords, defined by James E. Sheridan as “one who commanded a personal army, controlled or sought to control territory, and acted more or less independently.” Politically speaking, the revolution had not been a success – C.P. Fitzgerald, living in China at the time, described the situation as “an incomprehensible confusion. No principles appeared to be in conflict; no contest between democracy and tyranny was visible, no climax and no conclusion.”

However, Harold Tanner, writing 90 years later, argues that in this confusion, there was newly found intellectual freedom that was to have a major impact in the formation of political ideologies. As Tanner argues, “although the 1911 revolution failed to establish an effective government and did nothing at all to address rural poverty or other social issues, it did open the way for a period of intensified intellectual, cultural and social change. He argues that, “musicians, artists, educators and writers searched for the causes of China’s continued weakness and for ways to construct a robust modern Chinese national identity.” Students were sent to Europe and America to study; “their exposure to foreign countries only served to strengthen their nationalist consciousness.” Our Western understanding of nationalism did not exist as such. “Nationalism in its modern form was a Western import into China.” Heavily influenced by internationally educated students and intellectuals, China’s domestic policies took a pro-Western turn, with educational reforms that included Western studies, and a general westernisation that encouraged the rejection of Confucian values and instead promoted the idea of a new, “Young China”. The republic thus strived for equality with the Western powers, and saw the outbreak of World War I as potentially beneficial to this cause. As put by Rana Mitter, “The ideas of nationalism which had developed among a small elite exposed to European thought in the late nineteenth century had by now spread to many of the urban youth, who for the first time realised that their future lay in the modern, globalised world, utterly different from the old Confucian that lay in ruins.”

The Chinese Labour Corps

I) Background

China’s hands were tied in terms of the extent of the involvement they could have in the war, looking for ways to aid diplomatically that would, however, have enough impact to be recognised and benefit from. In June 1915, General Liang Shiyi and friend Ye Gong Chuo devised a scheme guaranteeing Chinese participation without officially breaking the country’s neutrality. Aware of the need for manpower on the Western Front, the General drew up a scheme he called “yigong daibing” , sending Chinese labour workers to aid the Allies. This move was to demonstrate China’s sincerity in its newly found internationalism, while hoping to benefit both financially and economically. The plan was approved and officially put in place at the 1916 War Committee in London, where the “Chinese Labour Corps” was founded. The workers were to serve in France, supported by non-governmental foreign companies, to avoid any accusation of China’s end to neutrality.

Previously, Chinese had travelled to work as so-called “coolies”, under contract or treaty provisions, “tempted to do so due to poor conditions in China and because of the comparatively high wages offered.” As one descendant recalls decades later, “They got no more than three to five silver dollars a year from toiling in the fields. Now, ten silvers for each month, who could resist the temptation?” Additionally, it was a chance for sheltered locals to gain experiences overseas.

French and British organisations advertised the CLC through media and old British missionaries.

Those under French recruitment were offered a completed 5-year contract, after which the workers could decide whether to stay or return to their homeland, and were promised equal rights to French civilians. They were to be placed well behind the frontlines and work in camps and factories. Those under British recruitment were disadvantaged – “each labourer was contracted to work for three years, but the army could terminate the contract after one year, giving six months notice. Compared to the contract workers signed with the French, the terms of the British were not at all favourable.” Nevertheless, the prospective benefits for the workers overshadowed the unreasonable contract terms, and the plan was successful – over the two remaining years of the war, the Allies shipped an estimated number of 140 000 “coolies” to Europe.

II) China’s Motives

Historically, China had always sought distance from the West, considering themselves superior and regarding European materialism with contempt. As early as 1717, Emperor Kangxi noted “there is cause for apprehension lest in centuries or millennia to come China may be endangered by collision with the nations of the West.” As argued by Harry Gelber, “China’s rulers distrusted foreign traders, especially Western ones, as liable to disturb the empire’s domestic peace, however much China needed the flow of foreign earnings.” There had been a long history of struggles between China and the West, most notably the Opium Wars against Britain that spanned from 1839-1860. Consequently, the general feeling within the population was one of increasing hostility as Europe’s presence in its country became more pronounced, earning them the name of the “foreign devils.” Harrington argues that the Boxer Uprising in 1900 “can be attributed directly to Chinese hatred of foreigners and foreign interference in their country. (…) In short, the Boxer Rebellion was a last grasp attempt to throw off the foreign yoke and preserve the Chinese culture, religion and way of life once and for all.” However, Leifer argues it was “necessary to adapt to Western ways if China were to strengthen itself and once again acquire the power and wealth to repel aggressors and re-establish its significance as a major centre of power and culture in the world.”

Chinese historian Xu Guoqi speaks in favour of this claim, arguing that “the Chinese (…) had been obsessed with one thing and one thing only since the turn of the century: how to join the world community as an equal member.” He point out the domestic benefits awaiting China through Westernisation: key figures in the Chinese government were seeking to work towards modern reforms for the Chinese population and its industry. “Social elites such as Li Shizeng and Cai Yuanpei believed that the nation needed citizens who had learned from abroad to propel reform.” The reason behind sending thousands of Chinese to France was the expectation that, upon return, “they would have an enormous impact on Chinese society.” The war provided the perfect opportunity for Li and his fellows to re-enforce their labour education plans. In their collective memo to the Chinese government, they argue that the recruitment programme would significantly develop Chinese national identity and secure a new position in the world. “Chinese labourers in France would be in the vanguard of this trend of learning from the West.”

As both sources confirm, China had faced a major shift in attitude and was now looking to re-establish itself. Disconnected from domestic European politics, China did not have any reason for an interest in what was happening on the European stage other than selfish motives. Consequently, this paradoxical reluctance to affiliate with Western materialism but longing for modernisation resulted in what Leifer calls an “anti-Western Westernisation.” By the outbreak of war in 1914, China was a country whose government was focused on international prestige to counteract their “historical frustrations” of inequality on the international scene. While obviously militarily inferior, regaining their status diplomatically seemed the best plan. The labour supply was important for Chinese international relations, not only as a means of winning a seat in the post war peace conferences, but to work towards equal treatment and respect, including the removal of foreign privileges in China.

III) CLC’s Role for the Allies

British historian Brian Fawcett emphasises the fact that Chinese labour overseas was not in the least uncommon, and was consequently considered a practical measure, rather than a symbolic gesture. Fawcett reasons that, “as the war progressed, Britain and her allies required more manpower for their forces, so releasing those men who were unloading necessary supplies and war material.” This is supported in a July 1916 speech by Churchill, Home Secretary at the time, addressing the House of Commons and laying out the reasons for British support of the labour plan: “I would not even shrink from the word Chinese for the purpose of carrying on the war. These are not times when people ought in the least to be afraid of prejudices. At any rate, there are great resources of labour in Africa and Asia, which, under proper discipline, might be the means of saving thousands of British lives and of enormously facilitating the whole progress and conduct of the war.” Clearly, the Allies saw no consequent obligations in the matter, lacking to give a clear indication or settlement of potential Chinese repayment for their efforts.

When compared with Chinese sources, however, a misunderstanding between China and the Allies, and Chinese over-expectation, is revealed. In an emotional attack against the Allies, a 2009 documentary on the CLC, commissioned by the government-run China Central Television (CCTV) takes a stance against the Allies. Claiming that China’s vehemence in its engagement with the Allied powers had no impact on their view of China, CCTV goes on to say that Britain and France accepted their proposal of the CLC for purely practical reasons without consideration of China’s diplomatic aims. This is not untrue - initially, Liang Shiyi’s proposal had been turned down on the grounds that any Chinese participation would only complicate matters. Similarly, Xu Guoqi adopts a cynical attitude towards the Allies, consistently portraying them as selfish and inconsiderate. While France saw the plan as hugely beneficial, Britain feared China’s involvement in a victory, perhaps entitling them to land previously occupied by Germany and the allies – “Chinese participation would therefore only cause geo-political complications and was ultimately detrimental to British interest.” Unsurprisingly, both Chinese sources focus particularly on what they deem racist and inhumane behaviour against the Chinese labourers, striving to find fault in Allied conduct. While there is reason to suspect an exaggeration of facts, particularly in the case of CCTV, being under governmental control, the sources valuably illustrate the strong emotional ties that China had, and continues to have, to the idea of the CLC – and the implications this popular sentiment may have had in the build up to the May Fourth Movement.

Treaty of Versailles and the Controversy of their Impact in WWI While China’s military participation in the war had indeed been minimal, their labour aid proved arguably successful for the Allied advantage. Particularly sensitive towards the role of the CLC in China’s first steps towards internationalisation, high hopes were riding on the sacrifices the CLC had made for the war and their significance in the country’s future. “In a telegram to the Chinese minister in London on January 25th, 1917, the Foreign Minister openly linked its labour scheme with its larger plans,” stating a list of conditions, of which the most important was that “Britain would help China secure a seat at the post war peace conference.” The Chinese arrived at the Paris Peace Conference with high expectations to regain its lost territory of Shandong, which included the port city of Qingdao, and finally enter the international scene as equals.

However, in his memoir, Lloyd George called China’s war contribution “insignificant.” Unknown to China, Japan had made a secret deal with Britain and France in 1917 that transferred German colonies in China to Japanese control in the case of an Allied victory. Indeed, the Allies never saw China’s role as important or worthy of acknowledgement. The few primary sources available, such as the derogatively named book “With the Chinks”, by former CLC lieutenant Daryl Klein, reveal a patronising attitude towards what Klein calls an unthreatening “race of Peter Pans, never having grown up.” More recent sources, such as Michael Summerskill’s “China on the Western Front” tend to gloss over the unpleasantries, elaborating instead on intercultural friendships.

A study of Chinese sources reveals an utterly different approach towards the importance of the CLC. Regularly emphasising the Chinese “betrayal” and their national importance, China refuses to comply with the Western view of the CLC’s insignificance. In the first extensive study of the CLC, only recently published in 2011, Xu Guoqi claims that, “from the day the labourers were recruited, France and Britain were not honest with them. They were promised by France and Britain that they would not be sent to the battle zones. But many Chinese died from the hostile bombing, precisely because they worked near the front. Nowhere in their contracts was it suggested that they would be subject to military rule, yet military supervision was exactly what they had to deal with.” He goes on to argue that, “Chinese labour and Chinese sacrifices in the war were brushed aside by the West.” Both Xu’s book and the CCTV documentary not only strive to justify their claim for territorial compensation, but also endeavour to highlight the CLC’s influence on Chinese nationalism.

Consequently, there was a monumental outcry in the country when the Treaty of Versailles denied China Shandong, instead transferring the territory to Japan. After an official protest, the Chinese delegation refused to sign the document. There was a strong feeling of betrayal by the West, particularly by the American President Woodrow Wilson, whose promise of the right of self-determination in his Fourteen Points had been interpreted as a reference to the Shandong problem.

In Beijing, students met in the capital and drafted a series of protest resolutions in what would be the start of the May Fourth Movement. As argued by Michael Dillon, “These controversial Shandong clauses of the Treaty of Versailles were to become the cause célèbre for patriotic Chinese and led to the radicalisation and politicisation of members of the intelligentsia who had hitherto been focusing on cultural, linguistic and literary reform.” This was the turning point for China’s future politics, turning its back on its strive towards westernisation – ultimately, it had been due to “Wilson’s failure to resolve the Shandong question, that Chinese intellectuals first decided to turn to Soviet Russia.”

The CLC’s Impact on China after WWI

I) Worker’s Education in Europe

Marilyn A. Levine argues the workers “did not fulfil the expected foreign policy objective” set out by the government, having achieved no further recognition by the Allies. However, Levine’s view is limited – not looking at the broader picture, namely the impact of the CLC on Chinese society. While having failed internationally, the CLC was to shape national identity by integrating scholars and labourers. The social divide between intellectuals and uneducated workers was great, with the majority of the population illiterate and ignorant to world affairs. The CLC marked the first organised contact between scholars and labourers. The Chinese YMCA, an “independent organization allied with the world movement” coincided with China’s pursuit of national identity and early efforts to join the world community as an equal member. The YMCA saw themselves in an imperative role for the workers in their global education and literacy. As written in one of the Association’s volumes, “They (the workers) would exert great influence upon China on their return. To help them to imbibe the true Christian spirit is to lay a good foundation for China’s future, which means so much to the future of the world.” In 1918, the International Committee of the YMCA recruited Chinese students who had been educated and lived in France, Britain and the United States to come and work for their fellow countrymen. The focus was less on theology, but on the teaching of the current world situation and the workings of international relations to the workers. Organised efforts, including lectures by Chinese scholars, were made to explain the Allied reasons behind war, China and the Chinese workers role in it, Western civilisation and the relationship between China and America.

To encourage labourer participation, workers wrote and submitted pieces on topics like “Chinese labourers in France and their relation to China”, “What is the Republic of China?”, “Why is China weak” and “How to improve education in China.” When the Shandong question came up, many labourers submitted letters using “rational words or angry sentences to express their strong opposition to giving Shandong to Japan.” Most importantly, the collaboration between scholars and workers would be revolutionary. Scholar Yan Yangchu recalls: “I had never associated with labourers before the war … we of the student class felt ourselves altogether apart from them. But in France I had the privilege of associating with them daily and knowing them intimately. I found that these men were just as good as I, and had just as much to them. The only difference between us was that I had had advantages and they hadn’t. During the war in France, it seemed that I was teacher to the labourers, but actually it was they who educated me.”

With a large percentage of workers illiterate and oblivious to the world and China’s history, their education in Europe was a turning point for the education of the poor working class, and the relationships formed with the scholars proved mutually beneficial. Both groups had always lived fundamentally separate, lacking contact or understanding of each other. Historians such as Summerskill and Levine only provide restricted analysis of the CLC, focusing primarily on their war contribution or their failed international impact, with only brief mention of the intelligentsia’s presence. It is only Chinese sources like Xu who extend the view to focus on their true importance, namely the domestic impact of this new relationship. Undoubtedly, this link was of vital importance for the formation of the workers’ and scholars’ ideas, with which they would both return to their homeland.

II) Action Taken by Workers and Intellectuals in China

Upon their return to China, the workers worldview had been effectually altered, having experienced the West at war, first hand. Influenced by ideas that they had picked up in Europe from Chinese intellectuals and locals, the labourers were cognizant of new political and social ideologies. Xu Guoqi claims that, “as a consequence, they wanted to do their share in shaping the new world order and improving China’s status in it.” Labourer Fu Shengsan wrote an article entitled “Chinese Labourers in France and their Contribution to the Motherland”, published in the “Chinese Labourer’s Weekly”: Chinese labourers “had not really understood the relationship between an individual and a nation before they came to Europe. When they witnessed the Europeans fighting for their country in the Great War, their own nationalism and patriotism was aroused as well.” Labourers were determined to educate others with the knowledge gained in Europe – Their experiences “helped them realize that Westerners were not superior to the Chinese, making them confident that China might become as strong as the West.” Upon their return to China, the politically awoken labourers took active interest in their domestic politics and their rights. CLC returnees had a profound effect in China itself. In Shanghai a syndicalist group called the Chinese Wartime Labourers Corps was formed. In Canton, returnees created 26 new unions “regarded as the first modern unions in China” These unions had a significant impact on local workers, influenced by the returnees’ ideas that inspired them to fight for their rights. In the early 1920s, union members frequently held strikes. The government was requested to make systematic plans for returnees, and devised a plan called “Anzi Huiguo Huagong Zhangcheng “ which made use of the technical skills workers had acquired in Europe and assigned them suitable jobs as a means of driving their economy.

However, while the workers had changed attitudes and new political motivation, being mere labourers, their impact was only felt locally. The spread of their national influence was therefore left up to the CLC intellectuals. Returning scholars had not been left untouched by their experiences, and it was ultimately them, inspired by the labourers, who changed China’s national identity. As Xiaorang Han argues, “Chinese intellectuals in the revolutionary period were deeply concerned about rural China and the Chinese peasantry, believing that villages and peasants were at the heart of their political programs for changing both rural China and China as a whole.” Most notable is the famous educator Yan Yangchu, known for his work in mass literacy and rural construction in China. Yan returned from the CLC convinced of the worker’s potential power and feeling responsible for their further education. What distinguished CLC intellectuals, whether Communist or not, from other scholars, was their political, rather than purely academic, drive. Unlike previous education plans, their campaigns were politically motivated. The mass education of those underprivileged was, in their eyes, the solution to China’s “acute national crisis.”

Essentially, the labourers were tremendously significant on China, but primarily through their contact with the intelligentsia. Comparing the achievements of returned workers with accomplishments of the intellectuals, the impact of the latter is clearly greater. While undoubtedly the workers supplied the foundation for the scholars’ political agenda, the influential changes were made by those with greater capability to do so.

Conclusion

The CLC represented China’s drive for internationalisation and the changing national identity, in which workers played an increasingly important role. The May Fourth Movement marked the beginning of a new national era. Workers and intellectuals alike fuelled the sentiment during that time, spreading patriotism and learning through China. Nevertheless, one must keep in mind that the workers were, ultimately, only workers. Upon their return, they could exert no monumental changes except to spread the word to fellow labourers and organise local campaigns. That is not to say they were insignificant–the CLC was a symbol of nationalism and political entity. Their main importance lay, however, in their influence over intellectuals who were to transform the country. The CLC bridged the gap between the labourers and scholars in a way that merged society closer than it had ever been. The study of this affiliation shows the irony of how the intelligentsia laid the foundation for worker’s political strength. Thanks to this relationship, workers gained an education that only reinforced their growing power, allowing them to become politically involved and helped them realise their strength – an attitude that would prove essential in the rise of Chinese Communism.

Word Count: 3989

FOOTNOTES:

Mackerras, 110 Roberts, 6 ibid, 355 Fitzgerald, 52 Tanner, 420 Mitter, 36 – 37 Wasserstrom, 85 Roberts, 335 Mitter, 36 Fawcett, 34 Literally translated as “labourers in the place of soldiers” Xu, 15 “Chinese Labour Corps During World War I.” New Frontiers. China Central Television. CCTV 9, Beijing. 3 December 2009. Television. Fawcett, 33 “Chinese Labour Corps During World War I.” New Frontiers. China Central Television. CCTV 9, Beijing. 3 December 2009. Television. Britain’s history with China proved helpful – up to 1906, Shandong had had a small armed force of 533 locals set up by the British called the “Chinese Corps” that had played a role in many of Britain’s Asian conflicts. Furthermore, the recruitment centres the British had used for Chinese labourers to South Africa were located there and still in good condition. Ibid. Interestingly, the Chinese word for “coolie” is the Chinese kǔ (meaning “suffering”) and lì (meaning “power”) Fawcett, 34 “Chinese Labour Corps During World War I.” New Frontiers. China Central Television. CCTV 9, Beijing. 3 December 2009. Television. A former teacher from Shandong recalls the reason behind his decision to become a coolie: “Who was winning the war did not interest me. I saw in this notice an opportunity I had not dreamed would be mine. Then and there I resolved to become a coolie myself in order to visit these foreign countries. Xu, 50 “Chinese Labour Corps During World War I.” New Frontiers. China Central Television. CCTV 9, Beijing. 3 December 2009. Television ibid Xu, 124 A British governmental report claims that out of all contracts made with the Chinese, this one “was, from our point of view, the most satisfactory. It gave us power to hold them for a long period of time with the option of getting rid of them in a moderately short time” Summerskill, 94 – 95 Kuß “Rezension von: Guoqi Xu, Strangers on the Western Front: Chinese Workers in the Great War” Wasserstrom, 96 Gelber, 155 ibid Hanes, Sanello, 13 Bickers, 5 Harrington, 7 Leifer, 26 Xu, 2 As an intellectual and politician who had studied and lived in France, Li praised France as a “model republic”, and encouraged Chinese to go overseas to learn from the West. In 1902, Li and fellow politician Wu Zhihui had already considered sending ordinary Chinese to Europe, seeing the education of common people as the best way to reform China. Xu, 200 ibid ibid Chen Duxiu, later to be one of the first leaders of the Chinese Communist Party, regarded the war “as a struggle against imperialism – an issue, he felt consistently, that was the most pressing matter facing China. Elleman, 142 ibid Xu, 2 . Already in 1914, Yuan Shikai had offered to aid Britain in joint operations against German positions in Shandong, including the port city Qingdao, only to be turned down by the Allies. Tanner, 440 Xu, 125 Tanner, 441 Fawcett, 33 Xu, 27 “Chinese Labour Corps During World War I.” New Frontiers. China Central Television. CCTV 9, Beijing. 3 December 2009. Television. ibid In fact, only after the staggering 400,000 casualties at the Battle of the Somme did Britain decide to take up the offer. Crampton, Lee, 21 “Chinese Labour Corps During World War I.” New Frontiers. China Central Television. CCTV 9, Beijing. 3 December 2009. Television. ibid, 125 Xu, 125 Lloyd George, 134 Macmillan, 342 Klein, 31 Xu, 241 Xu, 240 There is still major controversy surrounding the amount of Chinese labourer casualties, with Summerskill writing of 1834 deaths in France, 279 at sea, and 32 untraceable, out of 94,500 recruitments. (Fawcett, 50) The Sunday Times however, quotes British government figures saying that out of the 93,474 workers, 91,452 returned to China, 1949 died in Europe and 73 on the ship back home. (Hamilton-Peterson. Chinese Dig Britain’s Trenches. The Sunday Times. in Fawcett, 50) Meanwhile, the Chinese government claims 145,000 recruitments and over 20,000 deaths. (CCTV. “Series: The Chinese Labour Corps during World War I” China Central Television, 2009. 5. November 2012. ) The delegation had requested to sign the treaty “with reservations”, however Clemenceau turned this down on the grounds that Germany may ask to do the same. Andelman, 276 On first hearing the news, David Andelman provides an account of a Chinese delegate “flinging himself on the floor in a fury of frustration” whilst quoting Wilson: “You can rely on me.” ibid. ibid Dillon, 176 Elleman, 137 Xu, 241 ibid, 195 ibid, 175 ibid, 177 ibid, 185 “The education programme included classes on subjects such as English, French, history, mathematics, Chinese, and geography, among other subjects.” Ibid, 190 One of the most prominent and effective tools in their education was the Chinese Labourers’ Weekly, founded by scholar Yan Yangchu. This included short news bulletins in Chinese that kept the labourers informed of international events and later reported on what was happening at Versailles for the many who remained to clean up the battlefields after the armistice. Ibid, 206 ibid, 207 ibid, 208 Xu, 209 Obviously, their location in Europe gave them direct contact with locals and Allied soldiers and officers. While they were mostly confined to their camp, the Chinese workers still came into contact with Westerners from nearby villages. “Some labourers formed attachments with French women and often times children were born. At a later date they returned to China with their wives and children. The exact number is not known, but French sources quote 30 000, which appears excessive.” Fawcett, 50 ibid, 153 ibid ibid Lamb, 47 ibid ibid Translated as: “Regulations on Employment of Returned Labourers” Xu, Han, 1 Also known as James Yen, Yan later also went on to engage in mass education and rural reconstruction in other parts of Asia, gaining popular recognition for it. The China-raised American author Pearl S. Buck published a book of interviews with Yan called “Tell the People; Talks with James Yen About the Mass Education Movement” In 1985, the Chinese government officially acknowledged Yan’s contribution to Mass Education and Rural Reconstruction in China. Hayford, 30 Han, 1

From my website Echoes of War

Ruminghem Chinese Cemetery

This was the first CWGC I visited on the trip after being surprised to find on my map a 'cimetiere chinoise' apparently in the middle of nowhere. In fact, there are more Chinese dead than villagers.

The village itself lies between Calais and St. Omer and the cemetery is to the west of the village, and a little north of the road to Muncq-Nieurlet. This area had been the Headquarters of No. 11 Labour Group and a Chinese Hospital were stationed at Ruminghem. There are now over 70, 1914-18 war casualties commemorated in this site with 39 originally having been brought in from St. Pol-sur-Mer Chinese Cemetery. The cemetery covers an area of 340 square metres and is enclosed by a wall of rubble and flint.

Hard

to imagine in this isolated corner of Northern France a cemetery

containing Chinese is being continually maintained by the Commonwealth

War Graves Commission while I doubt anyone knows about these dead back

in China.

The

farmer who had offered to show me around when I arrived told me how,

only a few months earlier, two bodies had been identified (after 90

years!) and the stones were replaced with these markers while awaiting

new, inscribed headstones.

He

had told me that the Chinese Government intends to erect some kind of

memorial to the Chinese Labour Corps; can't fathom what propaganda

purpose that would serve in the new, strident and assertive China of

today...

Typical Chinese headstones found throughout France and Belgium.

This

field across from the cemetery is where most of these Chinese actually

died, clearing out the German ordnance, hence the dates indicating death

almost all come nearly a full year after the Armistice.As early as 1915 the Imperial War Graves Commission initiated a scheme to import and plant home grown maple seeds on Canadian graves; that same year the Australian wattle plant was planted on graves in Gallipoli. In the same spirit, cuttings of oleraia and Veronica traversii were imported from New Zealand. After the war the commission went to great lengths to ensure that only plants considered sacred and appropriate for commemoration were planted on Indian and Chinese graves. In this case you can see the two towering Gingko Bilbao trees which, this farmer informed me, had survived the atomic blast in 1945 (he didn't know which one) and brought here. In my schoolboy French I tried to explain that Chinese would not appreciate Japanese trees to be selected for the purpose, and perhaps willows would have been netter suited.

For a detailed examination of the Chinese serving in the Great War, you can read Brian C. Fawcett's THE CHINESE LABOUR CORPS IN FRANCE 1917-1921 at sunzi1.lib.hku.hk/hkjo/view/44/4400862.pdf The CWGC also has a three page leaflet on the Chinese Labour Corps which is available to download in pdf form at http://www.cwgc.org/admin/files/cwgc_clc.pdf

Les Baraques CWGC

The

graves of four men executed for murder are here- one British, Private J

Chandler, 10th Bn. Lincolnshire Regiment, and three men of the Chinese

Labour Corps.

The

Friends' War Victims' Relief Committee had originally been set up in

1871 by Quakers, and by the time of the war undertook relief and

reconstruction work overseas.

Ayette Indian and Chinese CWGC

A

Chinese pagoda takes the place of a cross, even though more Indians

(52) lie buried here than Chinese (33). One German lies here as well.

Albert French National Cemetery

The

first military cemetery I encountered as I cycled into Albert from the

east on the D938 was this French one which holds 3,175 French soldiers. I

didn't know until after that there is also one burial looked after by

the Commonwealth War Graves Commission - Wing Yuk Shan of the Chinese

Labour Corps, who died in December 1918.

The

first military cemetery I encountered as I cycled into Albert from the

east on the D938 was this French one which holds 3,175 French soldiers. I

didn't know until after that there is also one burial looked after by

the Commonwealth War Graves Commission - Wing Yuk Shan of the Chinese

Labour Corps, who died in December 1918.

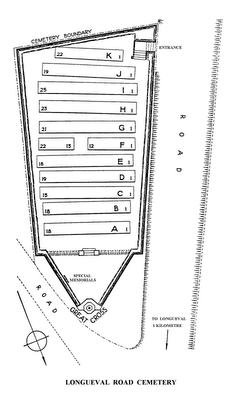

Longueval Road CWGC

This

cemetery is on the D197 south towards Maricourt and had been started

in September 1915. It was located near a dressing station which was

known as 'Longueval Alley', or 'Longueval Water Point'. Either a

trench, or even this very road, was known as Pall Mall in September

1916.

Many of the graves are from October and November 1916.

The graves are in regular rows, although within rows the spacing

between graves is quite varied. The Cross of Sacrifice is at the

triangular apex of the cemetery, and there are special memorials to two

men known and one believed to be buried here. From the Cross of

Sacrifice, one can look straight ahead over the cemetery to see

Bernafay Wood ahead. Trones wood can be seen to the left, with Delville

wood behind you. The road and track layout here is just the same today

as it was during the Great War.One soldier here merits especial attention for me: Serjeant Walter Poulter of 'B' Battery, 190th Brigade Royal Field Artillery died September 26, 1916, aged 29. He had actually come from China (where he had been serving with the Maritime Customs) with the Shanghai Volunteer Contingent.

Perth (China Wall) CWGC

The name refers to that given by soldiers to a communication trench known as the 'Great Wall Of China.'

The name refers to that given by soldiers to a communication trench known as the 'Great Wall Of China.'

A Welshman who had emigrated to Australia in 1913, Second

Lieutenant Frederick Birks was awarded the Military Medal during the

Battle of the Somme for leading a squad of stretcher-bearers in the

vicinity of Pozières and the V.C. for action at Glencorse Wood during

the Third Battle of Ypres (Passchendaele), September 21, 1917. From

his citation:

For most conspicuous bravery in attack, when, accompanied by only a corporal, he rushed a strong point which was holding up the advance. The corporal was wounded by a bomb, but 2nd Lt. Birks went on by himself, killed the remainder of the enemy occupying the position, and captured a machine gun. Shortly afterwards he organised a small party and attacked another strong point which was occupied by about twenty-five of the enemy, of whom many were killed and an officer and fifteen men captured. During the consolidation this officer did magnificent work in reorganising parties of other units which had been disorganised during the operations. By his wonderful coolness and personal bravery 2nd Lt. Birks kept his men in splendid spirits throughout. He was killed at his post by a shell whilst endeavouring to extricate some of his men who had been buried by a shell.

Major William Henry Johnston of the Royal Engineers, who

later was killed June 8, 1915, was awarded the V.C. at Missy-sur-Aisne

during the “Race to the Sea” after the Battle of the Marne which

stopped the Germans in front of Paris. From the citation:

Two of seven soldiers shot

at dawn buried in this cemetery, the left being the grave of Private

Thomas Docherty of the King's Own Scottish Borderers executed for

desertion in July 1915 and the other being the grave of Private George

Ernest Roe, of the King's Own Yorkshire Light Infantry, from

Sheffield, shot at dawn for desertion in June 1915, aged 19. On

November 7, 2006, the British government announced a pardon for all

soldiers executed in the Great War.

At Missy, on 14th Sept. [1914], under a heavy fire all day until 7 p.m., worked with his own hand two rafts bringing back wounded and returning with ammunition; thus enabling advanced Brigade to maintain its position across the river.

Both men here were shot July 26, 1915 with two others on the Ypres Ramparts for desertion. Private Fellows, a father back in Birmingham, was shot by firing squad with four other deserters from the 3rd Battalion on July 26, 1915. Corporal Ives was shot despite members of the court martial recommending mercy on the grounds that he may have been telling the truth when claiming that e had suffered memory loss from shellfire. However, his sentence of death was confirmed by the Field Marshal.

Private Evan Fraser of the Royal Scots was executed for desertion in August 1915, aged 19. He is commemorated on a special memorial, his original grave having been lost. Fraser absconded from his regiment at 4pm on 24 May 1915. He was arrested the next day at a local railway station in possession of a forged pass and handed back to the British. Whilst in British custody he escaped, but again was caught after little more than 24 hours. Two weeks later, he escaped custody for a second time and again was arrested within a day. On 13 July he was charged with having deserted on three occasions and of conduct to the prejudice of good order (having a forged pass). He was undefended at his trial. He pleaded guilty to the forgery, but not guilty to the counts of desertion. His battalion adjutant gave evidence, saying that Fraser was "a continual source of annoyance", a shirker and a continual deserter. He was shot at 4am on 2 August 1915

South of Béthune heading towards Arras is

Fosse #10 Communal Cemetery

This cemetery is located in an old mining village 20 kilometres north of Arras in the direction of Bethune called Sains-en-Gohelle. Seven Chinamen among the 471 war casualties commemorated here, having been moved from the Petit-Cuincy German Cemetery whilst the British soldiers were reburied after the Armistice in Douai British Cemetery: Chang Wen Chih, Chang Yen Tien, Chao Pang Hsieu, Chaw Chang Mai, Che Tso Cheng, Chia Bun Li and Chou Ching Yuan, all from the Chinese Labour Corps. The extension is on the south side of the communal cemetery and was begun in April 1916 to be used continuously until October 1918.who were The cemetery extension covers an area of 2,134 square metres and is enclosed by a brick wall.

For a detailed examination of the Chinese serving in the Great War, you can read Brian C. Fawcett's THE CHINESE LABOUR CORPS IN FRANCE 1917-1921 at sunzi1.lib.hku.hk/hkjo/view/44/4400862.pdf The CWGC also has a three page leaflet on the Chinese Labour Corps which is available to download in pdf form at http://www.cwgc.org/admin/files/cwgc_clc.pdf