As with England, the first written account of this area and its people was by its conqueror, Julius Caesar who had subdued the territories west of the Rhine that were occupied by the Eburones and across from Cologne east of the Rhine the Ubii and other Germanic tribes such as the Cugerni who were later settled on the west side of the Rhine in the Roman province of Germania Inferior. Kenneth Wellesley (91-92) describes this region during the year of the four emperors, describing the opportunities its destruction during the Second World War provided for archæologists:

At Cologne, the capital city of the Lower Rhine District, the saturation bombing of the 1939–45 war opened up the possibility of excavation. It was carefully conducted for many years. We now know the site and shape of the governor’s palace by the Rhine, and public spirited ingenuity has seen to it that the visitor can still, despite rebuilding, study something of the impressive remains in a large crypt beneath the Town Hall. Already in 69 a walled city with its municipality, Cologne, the colony of the people of Agrippina, had a permanent bridge over the Rhine, serving to connect it with many Transrhenane Germans and funnel the trade flow in both directions. No legion guarded it; but slightly further on, atBonn, just before the hills begin, lay the third station holding another single legion. A little before Koblenz a humble stream trickles into the latter from the west, flowing from a well-defined side valley penetrating the wooded hills; its name, the Vinxtbach, suggests that this was the frontier between Lower and Upper Germany, and inscriptions found north and south of the tributary make the supposition certain. At Mainz, where the inflowing Main forms a broad highway to and from the east, the double legionary fort was the main military site of the Upper District, of which the remaining legion lay now far to the south at Windisch in the Aargau. ... On the waters of the Rhine the ships of the German fleet gave further protection, and forwarded a useful riverborne supply of commodities and munitions.

The current German state of Rhine-Westphalia was created by the British when, after the war, they were tasked with ruling the largest and most populous of the four zones that Germany found itself divided into. The British military administration established it in 1946 from the Prussian provinces of Westphalia and the northern part of Rhine Province (North Rhine), and the Free State of Lippe. Giles MacDonogh summarises how great the task was that the British faced; my family didn't experience rationing growing up in England during the war; it did after:

The British needed to take stock of their zone. They had the largely empty farmlands of Schleswig-Holstein, the industrial and farming areas of Lower Saxony, and the industrialised but also highly cultural region of the Rhine and the Ruhr. The area had been very badly damaged by bombing. Cologne was 66 per cent destroyed, and Düsseldorf a staggering 93 per cent. Aachen was described as a ‘fantastic, stinking heap of ruins’. The British reordered their domain, creating Rhineland-Westphalia by amalgamating two Länder.Bad Godesberg

(255) After the Reich

The Rheinhotel Dreesen had been the site of a convention of SA and ϟϟ leaders on August 19, 1933 in which Hitler

delivered a two-and-a-half-hour address, commenting, among other things,

on the relationship between the SA and the Reichswehr. Eventually the hotel would be the site of Hitler's planning for the purge of the SA and its leader Ernst Röhm in June 1934.

The Rheinhotel Dreesen had been the site of a convention of SA and ϟϟ leaders on August 19, 1933 in which Hitler

delivered a two-and-a-half-hour address, commenting, among other things,

on the relationship between the SA and the Reichswehr. Eventually the hotel would be the site of Hitler's planning for the purge of the SA and its leader Ernst Röhm in June 1934.It was from this hotel, run by Herr Dreesen, an early Nazi crony of Hitler, that the Fuehrer had set out on the night of June 29-30, 1934, to kill Roehm and carry out the Blood Purge. The Nazi leader had often sought out the hotel as a place of refuge where he could collect his thoughts and resolve his hesitations.

Shirer (nb.349) Rise And Fall Of The Third Reich

When he first visited the hotel in 1926, Hitler signed himself in as a “stateless writer” and then often stopped there. even though the hotel owner at the time was considered a “ half-Jew ” in the sense of Nazi ideology and had a Jewish sister-in-law and numerous Jewish friends, but was able to continue operating his hotel unmolested. On June 29, 1934, Hitler met with Joseph Goebbels and Sepp Dietrich in preparation for the Röhm Putsch.The hotel also played host to meetings between Hitler and Chamberlain on September 21-23, 1938,

regarding Hitler's proposed annexation of the Sudetenland in

Czechoslovakia; before he flew to Bad Godesberg, Chamberlain aptly

remarked that he was setting out "to do battle with an evil beast." As

Kershaw relates,

When he first visited the hotel in 1926, Hitler signed himself in as a “stateless writer” and then often stopped there. even though the hotel owner at the time was considered a “ half-Jew ” in the sense of Nazi ideology and had a Jewish sister-in-law and numerous Jewish friends, but was able to continue operating his hotel unmolested. On June 29, 1934, Hitler met with Joseph Goebbels and Sepp Dietrich in preparation for the Röhm Putsch.The hotel also played host to meetings between Hitler and Chamberlain on September 21-23, 1938,

regarding Hitler's proposed annexation of the Sudetenland in

Czechoslovakia; before he flew to Bad Godesberg, Chamberlain aptly

remarked that he was setting out "to do battle with an evil beast." As

Kershaw relates, It was almost eleven o’clock when Chamberlain returned to the Hotel Dreesen. The drama of the late-night meeting was enhanced by the presence of advisers on both sides, fully aware of the peace of Europe hanging by a thread, as Schmidt began to translate Hitler’s memorandum. It demanded the complete withdrawal of the Czech army from the territory drawn on a map, to be ceded to Germany by 28 September. Hitler had spoken to Goebbels on 21 September of demands for eight days for Czech withdrawal and German occupation. He was now, late on the evening of 23 September, demanding the beginning of withdrawal in little over two days and completion in four. Chamberlain raised his hands in despair. ‘That’s an ultimatum,’ he protested. ‘With great disappointment and deep regret I must register, Herr Reich Chancellor,’ he remarked, ‘that you have not supported in the slightest my efforts to maintain peace.’Chamberlain and Ribbentrop leaving the Hotel Petersberg, on September 25, 1938.

At this tense point, news arrived that Beneš had announced the general mobilisation of the Czech armed forces. For some moments no one spoke. War now seemed inevitable. Then Hitler, in little more than a whisper, told Chamberlain that despite this provocation he would hold to his word and undertake nothing against Czechoslovakia – at least as long as the British Prime Minister remained on German soil. As a special concession, he would agree to 1 October as the date for Czech withdrawal from the Sudeten territory. It was the date he had set weeks earlier as the moment for the attack on Czechoslovakia. He altered the date by hand in the memorandum, adding that the borders would look very different if he were to proceed with force against Czechoslovakia. Chamberlain agreed to take the revised memorandum to the Czechs. After the drama, the meeting ended in relative harmony. Chamberlain flew back, disappointed but not despairing, next morning to London to report to his cabinet.

Despite his misgivings about the growing opposition to his policies at home, Mr. Chamberlain appeared to be in excellent spirits when he arrived at Godesberg and drove through streets decorated not only with the swastika but with the Union Jack to his headquarters at the Petershof, a castlelike hotel on the summit of the Petersberg, high above the opposite (right) bank of the Rhine. He had come to fulfill everything that Hitler had demanded at Berchtesgaden, and even more. There remained only the details to work out and for this purpose he had brought along, in addition to Sir Horace Wilson and William Strang (the latter a Foreign Office expert on Eastern Europe), the head of the drafting and legal department of the Foreign Office, Sir William Malkin. Late in the afternoon the Prime Minister crossed the Rhine by ferry to the Hotel Dreesen where Hitler awaited him. For once, at the start at least, Chamberlain did all the talking. For what must have been more than an hour, judging by Dr. Schmidt’s lengthy notes of the meeting, the Prime Minister, after explaining that following ”laborious negotiations” he had won over not only the British and French cabinets but the Czech government to accept the Fuehrer’s demands, proceeded to outline in great detail the means by which they could be implemented. Accepting Runciman’s advice, he was now prepared to see the Sudetenland turned over to Germany without a plebiscite. As to the mixed areas, their future could be determined by a commission of three members, a German, a Czech and one neutral. Furthermore, Czechoslovakia’s mutual-assistance treaties with France and Russia, which were so distasteful to the Fuehrer, would be replaced by an international guarantee against an unprovoked attack on Czechoslovakia, which in the future ”would have to be completely neutral.”

Shirer (349)

|

| Bonner Münster on June 6, 1941 and today |

Following the war, Bonn was in the British zone of occupation, and in 1949 became the de facto capital of the newly formed Federal Republic of Germany (the de jure capital of the Federal Republic throughout the years of the Cold War division of Germany was always Berlin). Nevertheless, Berlin's previous history as united Germany's capital was strongly connected with Imperial Germany, the Weimar Republic and more ominously with Nazi Germany. It was felt that a new peacefully united Germany should not be governed from a city connected to such overtones of war. Additionally, Bonn was closer to Brussels, headquarters of the EU. The heated debate that resulted was settled by the Bundestag only on June 20, 1991. By a vote of 338–320, the Bundestag voted to move the seat of government to Berlin. The vote broke largely along regional lines, with legislators from the south and west favouring Bonn and legislators from the north and east voting for Berlin. It also broke along generational lines as well; older legislators with memories of Berlin's past glory favoured Berlin, while younger legislators favoured Bonn. Ultimately, the votes of the 'Ossi' legislators tipped the balance in favour of Berlin.

Solemn hoisting of the swastika flag at Bonner Universität in February, 1933 and the site today

When Mr. President Roosevelt stutters about culture, then I can only say: what Mr. President Roosevelt calls culture, we call lack of culture. To us, it is a stupid joke. I have already declared a few times that just one of Beethoven’s symphonies contains more culture than all of America has managed to produce up to now! Strictly speaking, we colonised England and not the other way around.On the other side Churchill’s V-for-Victory device was used by the BBC in Morse code as the opening bar of Beethoven’s Fifth symphony. The house itself survived the war almost unscathed although during the air raid of the Bonn city centre on October 18, 1944, a fire bomb fell on the roof of Beethoven's birthplace. Thanks to the help of janitor Heinrich Hasselbach and Wildemans, who were later awarded the German Federal Cross of Merit, as well as Dr. Franz Rademacher from the Rhenish National Museum, the bomb did not ignite a conflagration. the connection with Beethoven no doubt induce the British to decide in Bonn’s favour when choosing the capital of the new Federal Republic of Germany by offering to make it autonomous and free from their control, helped too by the fact that Frankfurt was administratively too important for the Americans to relinquish.

Cologne (North Rhine-Westphalia)

Reichsadler found on the Autobahnbrücke Rodenkirchen. Rodenkirchen is a southern borough of Cologne.

Reichsadler found on the Autobahnbrücke Rodenkirchen. Rodenkirchen is a southern borough of Cologne.When the Nazis came to power in 1933, the Jewish population of Cologne was about 20,000. By 1939, 40% of the city's Jews had emigrated. The vast majority of those who remained had been deported to concentration camps by 1941. The trade fair grounds next to the Deutz train station were used to herd the Jewish population together for deportation to the death camps and for disposal of their household goods by public sale.

|

| Swastikas above the Kölner Eis-und Schwimmstadion and today |

On Kristallnacht in 1938, Cologne's synagogues were desecrated or set on fire. It was planned to rebuild a large part of the inner city, with a main road connecting the Deutz station and the main station, which was to be moved from next to the cathedral to an area adjacent to today's university campus, with a huge field for rallies, the Maifeld, next to the main station. The Maifeld, between the campus and the Aachener Weiher artificial lake, was the only part of this over-ambitious plan to be realized before the start of the war. After the war, the remains of the Maifeld were buried with rubble from bombed buildings and turned into a park with rolling hills, which was christened Hiroshima-Nagasaki-Park in August 2004 as a memorial to the victims of the nuclear bombs of 1945. An inconspicuous memorial to the victims of the Nazi regime is situated on one of the hills.

The city of Cologne was bombed 262 times during the Second World War,

more than any other German city, over 31 of which were heavy.

The city of Cologne was bombed 262 times during the Second World War,

more than any other German city, over 31 of which were heavy. On the night of May 30–31, 1942, Cologne was the target for the first thousand bomber raid of the war. Between 469 and 486 people, around 90% of them civilians, were reported killed, more than 5,000 were injured, and more than 45,000 lost their homes. It was estimated that up to 150,000 of Cologne's population of around 700,000 left the city after the raid. The Royal Air Force lost 43 of the 1,103 bombers sent. By the end of the war, 90% of Cologne's buildings had been destroyed by Allied aerial bombing raids, most of them flown by the RAF.

After that it was regularly bombarded until 1945. On the left is an image from a series of stamps, showing Sir Arthur Harris, with a Lancaster bomber from his command. It was his plan that brought about the indiscriminate area bombing of German cities, destroying houses and civilian morale as much as factories and military targets. As he stated,

The Nazis entered this war under the rather childish delusion that they were going to bomb everyone else, and nobody was going to bomb them. At Rotterdam, London, Warsaw, and half a hundred other places, they put their rather naive theory into operation. They sowed the wind, and now they are going to reap the whirlwind.

Images of Cologne's destruction

|

| The Rathausturm from the Alter Markt |

|

| An SA man walking through the Heumarkt, and today |

|

| Adolf-Hitler-Platz, now Ebertplatz. |

|

| Prinzenhof in 1939 and today |

|

| The Heumarkt in 1938 and today |

The attack caused about 2,500 fires in the

city, 1,700 of which were described by the Cologne fire brigade as

"large". Due to the efforts of the fire brigade and thanks to the

vastness of many streets, there was no fire storm , but the majority of

the damage was caused by fire and less by the explosive devices. Around

3,300 non-residential buildings were completely destroyed, 2,090

severely and 7,420 more easily damaged. This makes a total of 12,810

buildings in this category that have been hit.

The attack caused about 2,500 fires in the

city, 1,700 of which were described by the Cologne fire brigade as

"large". Due to the efforts of the fire brigade and thanks to the

vastness of many streets, there was no fire storm , but the majority of

the damage was caused by fire and less by the explosive devices. Around

3,300 non-residential buildings were completely destroyed, 2,090

severely and 7,420 more easily damaged. This makes a total of 12,810

buildings in this category that have been hit. The only military building that was damaged was an anti-aircraft position. On the other hand, 13,010 of civilian residential units, mostly in multi-storey houses, were completely destroyed, seriously and 22,270 more easily damaged. According to the report by the chief of police, 469 people were killed involving 411 civilians and 58 military officers, 5,027 were wounded and 45,132 homeless. The number of registered residents of Cologne decreased by around 11% in the next few weeks. It is estimated that between 135,000 and 150,000 of the 684,000 residents left the city after the attack.

The

RAF meanwhile lost 43 aircraft, which corresponds to approximately 4.5%

of the bombers used. 22 of them were shot down above or near Cologne,

sixteen elsewhere by anti-aircraft fire, 4 by night fighters, 2 in

attacks on surrounding airfields and 2 were lost in a collision.

The

RAF meanwhile lost 43 aircraft, which corresponds to approximately 4.5%

of the bombers used. 22 of them were shot down above or near Cologne,

sixteen elsewhere by anti-aircraft fire, 4 by night fighters, 2 in

attacks on surrounding airfields and 2 were lost in a collision. Later in the war there were "more 1000 bomber attacks" although only four-engine machines with a significantly higher bomb load were used.

On November 10, 1944, a dozen members of the anti-Nazi Ehrenfeld Group were hanged in public. Six of them were sixteen-year-old boys of the Edelweiss Pirates youth gang, including Barthel Schink; Fritz Theilen survived. The bombings continued and people moved out. On March 2, 1945, the RAF attacked Cologne for the last time with 858 bombers in two phases. As part of Operation Lumberjack, the first part of Cologne was captured by the 1st US Army a few days later. By May 1945 only twenty thousdand residents remained out of 770,000. The outskirts of Cologne were reached by American troops on March 4, 1945. The inner city on the left bank of the Rhine was captured in half a day on March 6, meeting only minor resistance. Because the Hohenzollernbrücke was destroyed by retreating German pioneers, the boroughs on the right bank remained under German control until mid-April 1945 before the British took over. As the director of the British Military Government, General Gerald Templer, put it, "[t]he city was in a terrible mess; no water, no drainage, no light, no food. It stank of corpses."

Hitler

inspecting a model of the cathedral and the real thing in 1936 when, on

March 28, Hitler arrived in Cologne and had himself celebrated

as the “liberator of the Rhineland” at an official reception in the

Giirzenich banquet hall. He received the praise of various

“liberated” districts and declared

Hitler

inspecting a model of the cathedral and the real thing in 1936 when, on

March 28, Hitler arrived in Cologne and had himself celebrated

as the “liberator of the Rhineland” at an official reception in the

Giirzenich banquet hall. He received the praise of various

“liberated” districts and declared

That Providence has chosen me to perform this act [restoring German military sovereignty in the Rhineland) is something I feel is the greatest blessing of my life.

The

cathedral in Cologne is Germany's most visited landmark, attracting an

average of thwenty thousand people a day, and currently the tallest twin-spired

church at a height of 515 feet, second in Europe after Ulm Minster and

third in the world. Together the towers for its two huge spires give the cathedral the largest façade of any church in the world. Its

construction began in 1248 but was halted in 1473, unfinished. Work did

not restart until the 1840s, and the edifice was completed to its

original mediæval plan in 1880. The choir has the largest height to

width ratio, 3.6:1, of any mediæval church. Cologne's mediæval builders

had planned a grand structure to house the reliquary of the Three Kings

and fit its role as a place of worship for the Holy Roman Emperor.

Despite having been left incomplete during the mediæval period, Cologne

Cathedral eventually became unified as "a masterpiece of exceptional

intrinsic value" and "a powerful testimony to the strength and

persistence of Christian belief in medieval and modern Europe" according

to UNESCO. Not mentioned is the fact that the cathedral has stones with swastikas, leading church bell expert Birgit Müller to remark that “[i]f these were taken out, the cathedral would have to be reconstructed.”

The

cathedral in Cologne is Germany's most visited landmark, attracting an

average of thwenty thousand people a day, and currently the tallest twin-spired

church at a height of 515 feet, second in Europe after Ulm Minster and

third in the world. Together the towers for its two huge spires give the cathedral the largest façade of any church in the world. Its

construction began in 1248 but was halted in 1473, unfinished. Work did

not restart until the 1840s, and the edifice was completed to its

original mediæval plan in 1880. The choir has the largest height to

width ratio, 3.6:1, of any mediæval church. Cologne's mediæval builders

had planned a grand structure to house the reliquary of the Three Kings

and fit its role as a place of worship for the Holy Roman Emperor.

Despite having been left incomplete during the mediæval period, Cologne

Cathedral eventually became unified as "a masterpiece of exceptional

intrinsic value" and "a powerful testimony to the strength and

persistence of Christian belief in medieval and modern Europe" according

to UNESCO. Not mentioned is the fact that the cathedral has stones with swastikas, leading church bell expert Birgit Müller to remark that “[i]f these were taken out, the cathedral would have to be reconstructed.”  The

Hohenzollern Bridge, with Cologne Cathedral and Museum Ludwig in the

background, after the war and as it appears today. Cologne was left

after the war with its cathedral seemingly the only intact building

whilst the Hohenzollern Bridge across which a faux German division

marched in 1936 is destroyed. The

Hohenzollern Bridge functioned as one of the most important bridges in

Germany during the war; even consistent daily

airstrikes did not badly damage it. On March 6, 1945 German military

engineers blew up the bridge as Allied troops began their assault on

Cologne. After Germany surrendered on May 8, 1945, the bridge was

initially made operational on a makeshift basis, but soon reconstruction

began in earnest. Originally, the

bridge was both a railway and road bridge but after its destruction in

1945 and its subsequent reconstruction, it was only accessible to rail

and pedestrian traffic. By May 8, 1948 pedestrians could again use the

Hohenzollern Bridge. The southern road traffic decks were removed so

that the bridge now only consisted of six individual bridge decks, built

partly in their old form. The surviving portals and bridge towers were

not repaired and were demolished in 1958; finally the following year

reconstruction of the bridge was completed.

The

Hohenzollern Bridge, with Cologne Cathedral and Museum Ludwig in the

background, after the war and as it appears today. Cologne was left

after the war with its cathedral seemingly the only intact building

whilst the Hohenzollern Bridge across which a faux German division

marched in 1936 is destroyed. The

Hohenzollern Bridge functioned as one of the most important bridges in

Germany during the war; even consistent daily

airstrikes did not badly damage it. On March 6, 1945 German military

engineers blew up the bridge as Allied troops began their assault on

Cologne. After Germany surrendered on May 8, 1945, the bridge was

initially made operational on a makeshift basis, but soon reconstruction

began in earnest. Originally, the

bridge was both a railway and road bridge but after its destruction in

1945 and its subsequent reconstruction, it was only accessible to rail

and pedestrian traffic. By May 8, 1948 pedestrians could again use the

Hohenzollern Bridge. The southern road traffic decks were removed so

that the bridge now only consisted of six individual bridge decks, built

partly in their old form. The surviving portals and bridge towers were

not repaired and were demolished in 1958; finally the following year

reconstruction of the bridge was completed.

On

the left is a closer view of what was the Schlagetersäule on

Rudolfplatz which in 1933 was renamed Schlageterplatz to which the

column with the Swastika-adorned flagpole was added. Albert Leo

Schlageter was born in Schönau in the Black Forest on August 12, 1894.

On May 26, 1923, he was shot because of sabotage in the Ruhr which had

been occupied by the French at that time. Because of the special

historical situation, Albert Leo Schlagter became the last soldier of

the Great War and, at the same time, the first soldier of the Third

Reich according to Nazi propaganda. Between 1919 and 1921 he was

involved as a volunteer corps member in battles in the Baltics and in

Upper Silesia as well as the suppression of a communist uprising in the

Ruhr. From 1922 Schlageter had been a member of the "Greater German

Labour Party," (Grossdeutschen Arbeiterpartei), a branch of the Nazi

Party. He ended up being betrayed after his sabotage during the

so-called "Ruhr struggle" against the French occupation forces, arrested

by the French occupation forces and on May 26, 1923, shot near

Dusseldorf.

On

the left is a closer view of what was the Schlagetersäule on

Rudolfplatz which in 1933 was renamed Schlageterplatz to which the

column with the Swastika-adorned flagpole was added. Albert Leo

Schlageter was born in Schönau in the Black Forest on August 12, 1894.

On May 26, 1923, he was shot because of sabotage in the Ruhr which had

been occupied by the French at that time. Because of the special

historical situation, Albert Leo Schlagter became the last soldier of

the Great War and, at the same time, the first soldier of the Third

Reich according to Nazi propaganda. Between 1919 and 1921 he was

involved as a volunteer corps member in battles in the Baltics and in

Upper Silesia as well as the suppression of a communist uprising in the

Ruhr. From 1922 Schlageter had been a member of the "Greater German

Labour Party," (Grossdeutschen Arbeiterpartei), a branch of the Nazi

Party. He ended up being betrayed after his sabotage during the

so-called "Ruhr struggle" against the French occupation forces, arrested

by the French occupation forces and on May 26, 1923, shot near

Dusseldorf. The Hahnentor sporting the swastika and today. As

with the aforementioned opportunities the destruction of Cologne

provided in the field of archæology, so too did it allow for urban

planning that had been held up before the war.

The Hahnentor sporting the swastika and today. As

with the aforementioned opportunities the destruction of Cologne

provided in the field of archæology, so too did it allow for urban

planning that had been held up before the war. for the

breakthrough in 1939. In August 1939 the breakthrough to the Hahnentor

was made. After

the war on the right, showing the severe damage. The Hahnentorburg was badly damaged

in the Second World War with the half tower on the left of the field

largely destroyed. After war, Rudolf Schwarz was commissioned to design the

entirety of Hahnenstrasse in mid-1945, and the war ruins in the street leading to the tower were

removed in 1946. Wilhelm Riphahn received an additional order from the

city to develop a concrete "development plan" for this connection

between Neumarkt and Rudolfplatz . In September 1945 he conceived his

“basic ideas for the redesign of Hahnenstraße / Cäcilienstraße” as a

promenade and cultural mile with a city character as well as an

architectural and visual connection between the high Wilhelminian-style

buildings on the ring and the buildings of the lower old town.

for the

breakthrough in 1939. In August 1939 the breakthrough to the Hahnentor

was made. After

the war on the right, showing the severe damage. The Hahnentorburg was badly damaged

in the Second World War with the half tower on the left of the field

largely destroyed. After war, Rudolf Schwarz was commissioned to design the

entirety of Hahnenstrasse in mid-1945, and the war ruins in the street leading to the tower were

removed in 1946. Wilhelm Riphahn received an additional order from the

city to develop a concrete "development plan" for this connection

between Neumarkt and Rudolfplatz . In September 1945 he conceived his

“basic ideas for the redesign of Hahnenstraße / Cäcilienstraße” as a

promenade and cultural mile with a city character as well as an

architectural and visual connection between the high Wilhelminian-style

buildings on the ring and the buildings of the lower old town. Gestapo Headquarters

Standing outside the cells which have been preserved from the original design of the cell block. The iron bars in front of the two staircases in the basement, the cell numbers and the door locks are still intact. Furthermore, a large number of wall inscriptions have been preserved, which can be seen primarily in cells 1 to 4 on Elisenstrasse. The indentations of the bunks can still be seen on the walls and floor, which were removed a few months before the end of the war to make more room in the cells, which were built for a maximum of two to three prisoners, but were severely overcrowded at the time were.

Standing outside the cells which have been preserved from the original design of the cell block. The iron bars in front of the two staircases in the basement, the cell numbers and the door locks are still intact. Furthermore, a large number of wall inscriptions have been preserved, which can be seen primarily in cells 1 to 4 on Elisenstrasse. The indentations of the bunks can still be seen on the walls and floor, which were removed a few months before the end of the war to make more room in the cells, which were built for a maximum of two to three prisoners, but were severely overcrowded at the time were.  Permission was granted to the Cologne Gestapo by the Reich Security Main Office in Berlin. Most executions took place on the gallows . Not far from the EL-DE house was a gallows frame from which seven people could be hanged at the same time. The corpses were buried in a designated Gestapo field in the western cemetery in Bocklemünd. Municipal refuse collection vehicles were used for transport to the cemetery. Today, 788 dead victims of the Gestapo are remembered in the cemetery. Many were also buried by their relatives in their home towns. The last execution at the EL-DE house took place on March 2, 1945, shortly before the American troops marched in.

Permission was granted to the Cologne Gestapo by the Reich Security Main Office in Berlin. Most executions took place on the gallows . Not far from the EL-DE house was a gallows frame from which seven people could be hanged at the same time. The corpses were buried in a designated Gestapo field in the western cemetery in Bocklemünd. Municipal refuse collection vehicles were used for transport to the cemetery. Today, 788 dead victims of the Gestapo are remembered in the cemetery. Many were also buried by their relatives in their home towns. The last execution at the EL-DE house took place on March 2, 1945, shortly before the American troops marched in. Since the walls have been painted over several times, around 1800 of the countless inscriptions can still be seen, which date from the period between the end of 1943 and 1945. Other inscriptions can only be guessed at. About 600 inscriptions in Cyrillic script are from Russians and Ukrainians, another 300 are written in French, Dutch, Polish, English and Spanish. After the war, some of the partitions between the cells were removed, such as cells 2 and 3 and cells 5 and 6. As a result, some inscriptions were lost.

Since the walls have been painted over several times, around 1800 of the countless inscriptions can still be seen, which date from the period between the end of 1943 and 1945. Other inscriptions can only be guessed at. About 600 inscriptions in Cyrillic script are from Russians and Ukrainians, another 300 are written in French, Dutch, Polish, English and Spanish. After the war, some of the partitions between the cells were removed, such as cells 2 and 3 and cells 5 and 6. As a result, some inscriptions were lost.

Wilhelmine Hömens, who testified before a British investigative court in 1947: “On March 1, 1945, a Stapo detail brought 70 to 80 girls and about 30 men tied together from the Klingelpütz on foot over the castle wall to the Stapo premises. They were Germans and mostly so-called Ostarbeiter. These people were all hung up on the Stapo premises, because I did not see the return transport, but found that around 5 p.m. three trucks with corpses were taken to the cemetery.”

Wilhelmine Hömens, who testified before a British investigative court in 1947: “On March 1, 1945, a Stapo detail brought 70 to 80 girls and about 30 men tied together from the Klingelpütz on foot over the castle wall to the Stapo premises. They were Germans and mostly so-called Ostarbeiter. These people were all hung up on the Stapo premises, because I did not see the return transport, but found that around 5 p.m. three trucks with corpses were taken to the cemetery.”  member

of the NS-Dozentenbund. In 1939 Schieder proposed the deportation of

several hundred thousand Poles as well as the "Entjudung" of the rest of

Poland in a "Polendenkschrift". By 1962 he became the rector of the

University of Cologne for two years.

member

of the NS-Dozentenbund. In 1939 Schieder proposed the deportation of

several hundred thousand Poles as well as the "Entjudung" of the rest of

Poland in a "Polendenkschrift". By 1962 he became the rector of the

University of Cologne for two years.

From Adolf-Hitler-Platz to Ebertplatz

The removal of some 13.5 million cubic meters of rubble from the centre of Cologne alone took over a year, to say nothing of the makeshift restoration of canals, bridges over the Rhine, and the central train station. As if the cleanup in the factories had not been hard enough, “the chief problems only emerged when actual production was restarted,” because the delivery of raw materials slowed and energy supplies remained unreliable. Time and again, frustrating bottlenecks thwarted a revival of activity. If the mines, for example, managed to extract sufficient coal, there would be “no rolling stock” available to transport it to either factories or homes. Likewise, supplying foodstuffs proved particularly difficult, since domestic production was unable to satisfy the needs of a population whose numbers had rapidly grown with the influx of refugees. Rationing of the shortages, moreover, led to a great deal of injustice, with some groups and areas inevitably getting more than others. Thus despite much hard work, by 1946 industrial production had only reached 50 to 55 percent of its pre-war level.Jarausch (82) After Hitler: Recivilising Germans, 1945–1995

Bad Honnef

During Reichskristallnacht in November 1938, the Honnefer synagogue, formerly an evangelical church, was set on fire on the Linzerstrasse near the Ohbach and was destroyed in this way. Many Jewish inhabitants emigrated. The Jews living in Honnef after 1939 had to leave their homes and were all concentrated within two houses in Honnef. From here they had to relocate to a camp in Much. In July 1941, transport to the east was carried out from Much to their deaths. In the Second World War, around 250 Honnef soldiers were killed and the city had three civilian casualties. Honnef had been largely spared from air raids in the Allied air war. One of the few destruction was that of the Penaten factory. For this reason, foreign authorities moved to the city, including parts of the Upper Prussianium of the Rhine province from Koblenz, the NSKOV to Linzerstrasse 108. Numerous prisoners of war and later forced labourers, especially women from the Soviet Union, worked in Honnef. An air attack on Honnef with bombs dropped onto Lohfelder Straße took place in November 1944. On the evening of March 10, 1945, the 331st Infantry Regiment of the 78th Infantry Division of the United States had occupied Honnef. Three days later the American combatants reached Hohenhonnef and the Rhine heights near Rhöndorf.

On Wednesday, February 7, 1945, the 3rd Battalion of the US 311th Infantry Regiment occupied a small, desperately resisting position of German infantry. The American march on the dam of the Rurtalsperre near Heimbach began. But General Rundstedt had left his demolition squads at this dam. On the following day, February 8, 1945, German engineers blew up the closures on the outlet pipes of the power plant in Schwammenauel , and now 100 cubic metres of water per second thundered into the bed of the Rur, causing a flood in the lowlands of the lowlands that, as it turned out several days later, did not bring the hoped-for success.

Dortmund (North Rhine-Westphalia)

|

| Hansaplatz in 1933 and during the 2006 World Cup |

|

| Hansaplatz 1938 with swastikas and today |

The

former Gestapo headquarters (and way station for those being sent to

concentration camps) today serves as the site for the exhibition Mahn- und Gedenkstätte Steinwache.

The

former Gestapo headquarters (and way station for those being sent to

concentration camps) today serves as the site for the exhibition Mahn- und Gedenkstätte Steinwache. Inside, shown below, is a reminder that from 1933 to 1945, over 66,000 people were imprisoned, some 30,000 of them for "political reasons".

commercial

ties with the Jews and shoppers staying away from stores owned by Jews.

Agitation against Jewish businessmen was intensified in the summer of

1935, with public boycotts organised in front of Jewish stores with

windows occasionally smashed. Anti-Jewish demonstrations were

accompanied by signs labelling the Jews as traitors, murderers,

warmongers and defilers of women. Jewish traders and entrepreneurs faced

a crowding-out campaign, which soon became an "Aryanisation" campaign.

Even before Kristallnacht, the beautiful synagogue on Hiltropwall in

Dortmund, which was in the immediate vicinity of the city theater on the

one hand and the Nazi district leadership on the other, was destroyed.

The synagogue in Hörde was set on fire by SA hordes and, like many

Jewish prayer houses, shops and apartments, looted and destroyed.

Immediately following Kristallnacht six hundred Jews were arrested, most

being sent to the Sachsenhausen concentration camp where seventeen

would die and others released only after paying extortionate demands.

Another five hundred Jews fled the city after the pogrom, leaving a

Jewish population of 1,444 by May 1939. Just 63 houses remained in

Jewish hands in September 1939 and at the end of the same year a mere

eighty businesses. With another two hundred Jews managing to leave after

the outbreak of war, 1,222 remained in June 1941 - these were left

without rights, property, homes or income. They were not allowed to use

public shelters, radios, telephones, or even the streets without

authorization. Gradually they were confined to “Jewish houses.”

commercial

ties with the Jews and shoppers staying away from stores owned by Jews.

Agitation against Jewish businessmen was intensified in the summer of

1935, with public boycotts organised in front of Jewish stores with

windows occasionally smashed. Anti-Jewish demonstrations were

accompanied by signs labelling the Jews as traitors, murderers,

warmongers and defilers of women. Jewish traders and entrepreneurs faced

a crowding-out campaign, which soon became an "Aryanisation" campaign.

Even before Kristallnacht, the beautiful synagogue on Hiltropwall in

Dortmund, which was in the immediate vicinity of the city theater on the

one hand and the Nazi district leadership on the other, was destroyed.

The synagogue in Hörde was set on fire by SA hordes and, like many

Jewish prayer houses, shops and apartments, looted and destroyed.

Immediately following Kristallnacht six hundred Jews were arrested, most

being sent to the Sachsenhausen concentration camp where seventeen

would die and others released only after paying extortionate demands.

Another five hundred Jews fled the city after the pogrom, leaving a

Jewish population of 1,444 by May 1939. Just 63 houses remained in

Jewish hands in September 1939 and at the end of the same year a mere

eighty businesses. With another two hundred Jews managing to leave after

the outbreak of war, 1,222 remained in June 1941 - these were left

without rights, property, homes or income. They were not allowed to use

public shelters, radios, telephones, or even the streets without

authorization. Gradually they were confined to “Jewish houses.” The main railway station in 1944 and today. Through it, Dortmund was used as a

central point for deportations to the East; between 1942 and 1945 there

were eight transports, each containing about 5,000 Jews, including the

Jews of Dortmund. On April 27, 1942 the largest group of Jews from

Dortmund numbering 700 -800 was deported to Zamosc in the Lublin

district of Poland and from there sent to the Belzec death camp, which a

month earlier had commenced gassing Jewish communities in the

Generalgouvernment. Of the approximately

4,500 Dortmunders of Jewish origin, two thousand were later murdered in

concentration camps. On January 27, 1942, the first deportation of over

1,000 Jews from the Arnsberg region from Dortmund to Riga took place.

The last deportation took place on February 13, 1945 to Theresienstadt.

But not only citizens of Jewish origin, but also members of other

"racial" or socially discriminated minorities like those of the Sinti

and Roma were persecuted and deported from Dortmund to the Nazi

extermination camps.

The main railway station in 1944 and today. Through it, Dortmund was used as a

central point for deportations to the East; between 1942 and 1945 there

were eight transports, each containing about 5,000 Jews, including the

Jews of Dortmund. On April 27, 1942 the largest group of Jews from

Dortmund numbering 700 -800 was deported to Zamosc in the Lublin

district of Poland and from there sent to the Belzec death camp, which a

month earlier had commenced gassing Jewish communities in the

Generalgouvernment. Of the approximately

4,500 Dortmunders of Jewish origin, two thousand were later murdered in

concentration camps. On January 27, 1942, the first deportation of over

1,000 Jews from the Arnsberg region from Dortmund to Riga took place.

The last deportation took place on February 13, 1945 to Theresienstadt.

But not only citizens of Jewish origin, but also members of other

"racial" or socially discriminated minorities like those of the Sinti

and Roma were persecuted and deported from Dortmund to the Nazi

extermination camps. |

| Book burning in front of the Amtshaus |

The

Market operating in Hansaplatz with the swastika adorning the maypole

during the Nazi era and today. Only with the armaments programme,

accompanied by an improvement in the global economy, did the mining and

steel and iron industries benefit from the Nazis' four-year plans, which

further solidified Dortmund's economic monostructure. From 1937

onwards, total production rose sharply and the unemployment rate fell

rapidly. The Ruhr region industry, and above all coal chemistry, became

increasingly important in the efforts to prepare for war, to secure an

adequate fuel supply for the increasing motorization of the Wehrmacht

and the economy, and to replace the missing

oil. The situation for Nazi Germany soon turned around as a result of

the war. The war already affected the home front in 1943. Despite the

most ruthless exploitation of foreign forced labourers, in particular

Eastern European prisoners of war, concentration camp

prisoners and abducted workers - 45,000 foreign forced labourers were

still employed in the relevant factories and mines in Dortmund alone

during the last year of the war - the arms industry and other branches

of production collapsed.

The

Market operating in Hansaplatz with the swastika adorning the maypole

during the Nazi era and today. Only with the armaments programme,

accompanied by an improvement in the global economy, did the mining and

steel and iron industries benefit from the Nazis' four-year plans, which

further solidified Dortmund's economic monostructure. From 1937

onwards, total production rose sharply and the unemployment rate fell

rapidly. The Ruhr region industry, and above all coal chemistry, became

increasingly important in the efforts to prepare for war, to secure an

adequate fuel supply for the increasing motorization of the Wehrmacht

and the economy, and to replace the missing

oil. The situation for Nazi Germany soon turned around as a result of

the war. The war already affected the home front in 1943. Despite the

most ruthless exploitation of foreign forced labourers, in particular

Eastern European prisoners of war, concentration camp

prisoners and abducted workers - 45,000 foreign forced labourers were

still employed in the relevant factories and mines in Dortmund alone

during the last year of the war - the arms industry and other branches

of production collapsed. |

| Luftwaffe Nazi eagle remaining on the façade of the police academy |

|

| Another continues to look down on the city |

The Hohensyburg memorial, shown with Nazi flags in front from period

postcards and today, located on a hill in the southern Dortmund district

of Syburg. The memorial was erected in memory of Kaiser Wilhelm I from

1893 to 1902 and opened to the public on June 30, 1902. Under the Nazis

the memorial was completely rebuilt in 1935 according to plans by the

Dortmund sculptor Friedrich Bagdons and redesigned based on the National

Socialist architecture. Of the four accompanying statues, those of

Crown Prince Friedrich Wilhelm and Prince Friedrich Karl (both by Karl

Donndorf) were removed whilst those of Otto von Bismarck and Helmuth von

Moltke (also by Adolf Donndorf) were preserved in a different

arrangement. On an inscription removed after 1945, March 16, 1935 was

given as the date of completion. Nearby are the remains of the castle,

partially destructed in 1287 by Count Eberhard von der Mark and probably

eventually abandoned in the 16th or early 17th century. Inside its

ruins is the war memorial dating from 1930 designed by the sculptor

Friedrich Bagdons. It depicts a lying fallen soldier in the uniform of a

German war participant from the First World War. At the level of his

left lower leg an eagle stands guard. In the immediate vicinity of the

war memorial there are three stone plaques erected by the Syburg

community in memory of the victims of the Syburg war from the

Franco-Prussian war and both world wars.

The Hohensyburg memorial, shown with Nazi flags in front from period

postcards and today, located on a hill in the southern Dortmund district

of Syburg. The memorial was erected in memory of Kaiser Wilhelm I from

1893 to 1902 and opened to the public on June 30, 1902. Under the Nazis

the memorial was completely rebuilt in 1935 according to plans by the

Dortmund sculptor Friedrich Bagdons and redesigned based on the National

Socialist architecture. Of the four accompanying statues, those of

Crown Prince Friedrich Wilhelm and Prince Friedrich Karl (both by Karl

Donndorf) were removed whilst those of Otto von Bismarck and Helmuth von

Moltke (also by Adolf Donndorf) were preserved in a different

arrangement. On an inscription removed after 1945, March 16, 1935 was

given as the date of completion. Nearby are the remains of the castle,

partially destructed in 1287 by Count Eberhard von der Mark and probably

eventually abandoned in the 16th or early 17th century. Inside its

ruins is the war memorial dating from 1930 designed by the sculptor

Friedrich Bagdons. It depicts a lying fallen soldier in the uniform of a

German war participant from the First World War. At the level of his

left lower leg an eagle stands guard. In the immediate vicinity of the

war memorial there are three stone plaques erected by the Syburg

community in memory of the victims of the Syburg war from the

Franco-Prussian war and both world wars.Essen

Renamed Adolf-Hitler-Platz in 1933 and serving as the main site for Nazi demonstrations in Essen, the main square reverted back to Burgplatz after the war. Here the Volkshochschule on Burgplatz 1 is decked out in Nazi regalia.

After the right-wing Kapp Putsch in Berlin had failed in the spring of 1920, the Rote Ruhrarmee rose up against the SPD-led national government with street fighting in Barmen , Duisburg, Elberfeld , Esseb, Remscheid and Velbert. On March 19, 1920 armed "Bolshevik" groups in Essen marched up to the site where civil defence units of the police and Home Guards waited; forty were killed. It was the largest resistance movement that has taken place in Germany since the peasant wars of the 16th century.

Burgplatz on the left in 1941 with the Johanneskirche and Münsterkirche and today.

Burgplatz on the left in 1941 with the Johanneskirche and Münsterkirche and today.Hitler had visited Essen a number of times. During one speech he made here at the Exhibition Grounds on November 2, 1933 Hitler claimed that "I will never sign anything knowing that it can never be upheld, because I am determined to abide by what I sign." The following year on June 28 Hitler and Göring went to Essen to attend the church wedding ceremony of the Essen Gauleiter, Josef Terboven. This was taking place during the so-called Night of Long Knives during which he purged his own followers in the SA. While he had been in Essen and had toured the labour camps in the West German Gaue in order to create the outer appearance of absolute calm so that the traitors might not be warned, the plan of carrying out a thorough purge had been fixed to the last detail.

Our Nationalists have not managed to redeem the national idea from its isolation, which only made it understandable to the intelligentsia, and have not been able to make the mass of the "people of the fist" its bearers. Our socialists have not managed to root the social world of ideas as the world of wishes of the masses in the will to fulfill of the intelligentsia. Both walk side by side and each insist on his "privilege". But that is the meaning of the National Socialist idea, to combine one with the other. In truth, a nationalist is not someone who teaches the worker to sing patriotic songs and cheer 'hurrah', but rather someone who creates the weapons for his people that are needed in all areas of life to fight for life. These weapons consist not only in a sound mind, but also in a sound body. Anyone who tries to help our people living in misery by improving their opportunities to make life physically healthy is a nationalist, and whoever also gives them the mental opportunities, the pride of the German citizen in his country, his people, his culture. To understand its history and to empathise with it fulfills its national task completely. But being a socialist is the same. Anyone who wants to be a socialist has to serve his people so that they can hold their own in the brutal struggle for life among peoples. Because in this fight only the strongest will survive. That is the iron logic of nature and her highest right, that she only lets the strongest and best live and the lazy and weak die. - If a new concept of community is to be formed from this knowledge, there is only one way: that the social power of the broad masses be paired with the national idea of the intelligentsia. It is the task of the Hitler movement to work towards this end. The way is not one of compromise, of lazy fraternisation of these two elements, but a new faith must arise. Only faith can reform as the Christian faith reformed the world. That is the mission, to shape the concept of this new faith and bring it to life.

.gif) The

fact that many of the first business circles followed this lecture is

the best proof of the importance that the National Socialist movement

has already reached under Hitler's leadership.The impression made by

Hitler's one-and-a-half-hour lecture can be judged by the great

attention with which one listened to it and the applause that was given

to it at the end."

The

fact that many of the first business circles followed this lecture is

the best proof of the importance that the National Socialist movement

has already reached under Hitler's leadership.The impression made by

Hitler's one-and-a-half-hour lecture can be judged by the great

attention with which one listened to it and the applause that was given

to it at the end."Also shown on the left in 1941 and today, Adolf-Hitler-Platz, now Willy-Brandt-PlatIt had fomerly been Burgplatz and had marked the historic core of Essen. According to written sources, there was an early mediæval courtyard here, from which the Essen convent for women was founded in the 9th century. Excavations in the 1920s and 1940s uncovered various remains of buildings and fortifications. In 1933, the Nazis renamed Burgplatz Adolf-Hitler-Platz and used the square, which had been the central meeting place in Essen since the mid-18th century, for their rallies and meetings. This took place after the Nazis had taken over the town in 1933 with Theodor Reismann-Grone appointed Mayor of Essen on December 21, 1932, initially on an acting basis after replacing Heinrich Maria Martin Schäfer before being put on leave on April 5, 1933 and later retired. Essen was subsequently divided into 27 local Nazi Party groups, whose offices are listed in the 1939 address book of the city of Essen. After the war, the first major events of the newly founded democratic parties took place here.

The SA being sworn in on Hitler-Platz on March 9, 1933. During

the war, the industrial town of Essen was a target of Allied strategic

bombing. Given that the Krupp steelworks was an important industrial

target, Essen was a "primary target" designated for area bombing by the

February 1942 British Area bombing directive. As part of the campaign in

1943 known as the Battle of the Ruhr, Essen was especially a regular

target. As a deception, the Krupp night light system was erected as a

dummy on Rottberg ten miles away. The attack on Essen marked the

beginning of a five-month British air offensive that lasted until

mid-July 1943 and became known as the Battle of the Ruhr. The 26 air

raids in 1942 caused relatively little destruction; In 1943 heavy

bombardments followed. On March 5, 1943, over 442 aircraft took off from

airfields in East and Central England. The Krupp works and downtown

Essen are marked as destinations. The attacks on the inner city and

densely populated working-class areas were part of the UK's area bombing

directive as around 360 bombers dropped around 1,100 tonnes of

high-explosive and incendiary bombs on the city in three waves within an

hour. At least 457 people were killed and over 3,000 buildings were

completely destroyed, leaving tens of thousands homeless. The Krupp

works suffered major damage for the first time.

The SA being sworn in on Hitler-Platz on March 9, 1933. During

the war, the industrial town of Essen was a target of Allied strategic

bombing. Given that the Krupp steelworks was an important industrial

target, Essen was a "primary target" designated for area bombing by the

February 1942 British Area bombing directive. As part of the campaign in

1943 known as the Battle of the Ruhr, Essen was especially a regular

target. As a deception, the Krupp night light system was erected as a

dummy on Rottberg ten miles away. The attack on Essen marked the

beginning of a five-month British air offensive that lasted until

mid-July 1943 and became known as the Battle of the Ruhr. The 26 air

raids in 1942 caused relatively little destruction; In 1943 heavy

bombardments followed. On March 5, 1943, over 442 aircraft took off from

airfields in East and Central England. The Krupp works and downtown

Essen are marked as destinations. The attacks on the inner city and

densely populated working-class areas were part of the UK's area bombing

directive as around 360 bombers dropped around 1,100 tonnes of

high-explosive and incendiary bombs on the city in three waves within an

hour. At least 457 people were killed and over 3,000 buildings were

completely destroyed, leaving tens of thousands homeless. The Krupp

works suffered major damage for the first time.  Another view of Adolf-Hitler-Platz on the right, seen from the north.

Another view of Adolf-Hitler-Platz on the right, seen from the north.

.gif) After

the German defeat in 1918, the company fell into a severe depression

due to a lack of orders and lost tens of thousands of jobs. After this

experience, despite the pressure from Berlin, Krupp boss Gustav Krupp

shied away from becoming too one-sided in the armaments business,

focussing more on custom-made products and mechanical engineering for

global export such as in locomotive and engine construction rather than

the mass production of grenades and cannons. The armaments share at

Krupp grew slowly at first, but eventually reached 42% in the 1938/39

financial year. At the beginning of the war Krupp was declared a

"Wehrmachtsbetrieb" and the influence of the civilian company management

declined rapidly. Since then, orders important to the war had absolute

priority, and exports were only permitted to allied countries. Economic

historian Werner Abelshauser writes that Krupp was dragged further and

further into the quagmire of the war economy and, as an "icon of German

pride in arms", increasingly attracted the hatred of those opposed to

the war.

After

the German defeat in 1918, the company fell into a severe depression

due to a lack of orders and lost tens of thousands of jobs. After this

experience, despite the pressure from Berlin, Krupp boss Gustav Krupp

shied away from becoming too one-sided in the armaments business,

focussing more on custom-made products and mechanical engineering for

global export such as in locomotive and engine construction rather than

the mass production of grenades and cannons. The armaments share at

Krupp grew slowly at first, but eventually reached 42% in the 1938/39

financial year. At the beginning of the war Krupp was declared a

"Wehrmachtsbetrieb" and the influence of the civilian company management

declined rapidly. Since then, orders important to the war had absolute

priority, and exports were only permitted to allied countries. Economic

historian Werner Abelshauser writes that Krupp was dragged further and

further into the quagmire of the war economy and, as an "icon of German

pride in arms", increasingly attracted the hatred of those opposed to

the war..gif) Today

the building is one of the largest and best-preserved architectural

testimonies of pre-war Jewish culture in Germany. It's the largest

free-standing synagogue building north of the Alps, even larger in terms

of volume than the New Synagogue in Berlin. Its free-floating dome is

37 metres high and the building seventy metres long in total. From the

start it was the cultural and social centre of a community with around

4,500 members in 1933 when the Nazis took power, having a main room for

over 1,500 people with several galleries, an organ and a large bimah

area (which was also often used for concerts), a weekday synagogue,

classrooms, a community hall, a secretariat, a library, a garden and

apartments for rabbis and cantors in the rabbi's house. It's shown on

the left in 1915 and today; on the right is it in flames on the night of

November 9-10, 1938, during the November pogroms. Badly damaged inside

by arson, its appearance nevertheless remained almost intact. Due to its

massive construction made of reinforced concrete, the Nazis couldn't

demolish the building contrary to their plans; demolition was further

made impossible because of the surrounding houses. The building ended up

surviving the war without major damage.

Today

the building is one of the largest and best-preserved architectural

testimonies of pre-war Jewish culture in Germany. It's the largest

free-standing synagogue building north of the Alps, even larger in terms

of volume than the New Synagogue in Berlin. Its free-floating dome is

37 metres high and the building seventy metres long in total. From the

start it was the cultural and social centre of a community with around

4,500 members in 1933 when the Nazis took power, having a main room for

over 1,500 people with several galleries, an organ and a large bimah

area (which was also often used for concerts), a weekday synagogue,

classrooms, a community hall, a secretariat, a library, a garden and

apartments for rabbis and cantors in the rabbi's house. It's shown on

the left in 1915 and today; on the right is it in flames on the night of

November 9-10, 1938, during the November pogroms. Badly damaged inside

by arson, its appearance nevertheless remained almost intact. Due to its

massive construction made of reinforced concrete, the Nazis couldn't

demolish the building contrary to their plans; demolition was further

made impossible because of the surrounding houses. The building ended up

surviving the war without major damage..gif) In

the time of the witch hunts around 1630, witch inspector Heinrich

Schultheiss led the witch trials in Erwitte. In 1630 the Westerkötter

complained that "unfortunately this inquisition, execution and

extermination of the witches was far too lenient" even though the

Erwitter pastor Jodocus Boget was burned at the stake that year for

witchcraft.

In

the time of the witch hunts around 1630, witch inspector Heinrich

Schultheiss led the witch trials in Erwitte. In 1630 the Westerkötter

complained that "unfortunately this inquisition, execution and

extermination of the witches was far too lenient" even though the

Erwitter pastor Jodocus Boget was burned at the stake that year for

witchcraft. .gif) During

this time, the castle was extensively renovated under the direction of

the architect Julius Schulte-Frohlinde. In addition, a number of

outbuildings were built such as the Horst-Wessel-Halle, part of a school

complex for the DAF also designed by Julius Schulte-Frohlinde with the

Nazi eagle sculpture that remains in situ by Willy Meller. In 1934, at

the suggestion of Albert Speer, who by then was already overburdened

with orders, Schulte-Frohlinde became deputy head of DAF's own

construction department, and from 1936 head of this DAF architectural

office. Besides Erwitte, he designed the Nazi training castles Sassnitz

on Rügen, arranged folk festivals in Berlin, Nuremberg and Hamburg as

well as the First International Crafts Exhibition in 1938 in Berlin and

undertook the construction of the DAF community centre in Berlin. In the

course of the reorganisation of the offices of the DAF, he was also

responsible for the planning department of the Reichsheimstättenamt ,

where he was responsible, among other things, for the training and

recruitment of architects in the planning departments of the

Gauheimstättenamt.

During

this time, the castle was extensively renovated under the direction of

the architect Julius Schulte-Frohlinde. In addition, a number of

outbuildings were built such as the Horst-Wessel-Halle, part of a school

complex for the DAF also designed by Julius Schulte-Frohlinde with the

Nazi eagle sculpture that remains in situ by Willy Meller. In 1934, at

the suggestion of Albert Speer, who by then was already overburdened

with orders, Schulte-Frohlinde became deputy head of DAF's own

construction department, and from 1936 head of this DAF architectural

office. Besides Erwitte, he designed the Nazi training castles Sassnitz

on Rügen, arranged folk festivals in Berlin, Nuremberg and Hamburg as

well as the First International Crafts Exhibition in 1938 in Berlin and

undertook the construction of the DAF community centre in Berlin. In the

course of the reorganisation of the offices of the DAF, he was also

responsible for the planning department of the Reichsheimstättenamt ,

where he was responsible, among other things, for the training and

recruitment of architects in the planning departments of the

Gauheimstättenamt. .gif) When

the general inspector for German roads, Fritz Todt, commissioned

Schulte-Frohlinde to "ensure the most economical and architecturally

flawless further development of housing", Schulte-Frohlinde was able to

expand his area of work. For the increased rationalisation of housing

construction, the DAF construction department developed construction

sheets with "Reichsbauformen" and "Landschaftsbauformen", which -

related to the typology of German landscapes - laid down floor plan

types, facade patterns, plan sheets for individual houses. When in

1935-36 in Braunschweig- Mascherode a Nazi model settlement of the

German Labour Front was to be founded, Schulte-Frohlinde became head of

the architecture office of the DAF for this settlement. With its mixture

of small settlements, single-family houses, terraced houses and rental

apartments, as well as the structure around a central square with a

community house, the picture of a traditional village was created, which

architecturally symbolised the Nazi ideal of ties to the home soil. In

1936 he designed the Strength Through Joy city for the Olympic Games in

Berlin.

When

the general inspector for German roads, Fritz Todt, commissioned

Schulte-Frohlinde to "ensure the most economical and architecturally

flawless further development of housing", Schulte-Frohlinde was able to

expand his area of work. For the increased rationalisation of housing

construction, the DAF construction department developed construction

sheets with "Reichsbauformen" and "Landschaftsbauformen", which -

related to the typology of German landscapes - laid down floor plan

types, facade patterns, plan sheets for individual houses. When in

1935-36 in Braunschweig- Mascherode a Nazi model settlement of the

German Labour Front was to be founded, Schulte-Frohlinde became head of

the architecture office of the DAF for this settlement. With its mixture

of small settlements, single-family houses, terraced houses and rental

apartments, as well as the structure around a central square with a

community house, the picture of a traditional village was created, which

architecturally symbolised the Nazi ideal of ties to the home soil. In

1936 he designed the Strength Through Joy city for the Olympic Games in

Berlin. .gif) The

folowing year he joined the Nazi Party. His conservative,

traditionalist construction style shaped the housing architecture of the

Third Reich and thus represented the most significant influence of the

Stuttgart School on building under the Nazis. The Horst-Wessel-Halle

today, no longer with the Nazi eagle-mounted column as seen in the

period photo. Schulte-Frohlinde also belonged to the movement's ideology

as seen in his foreword to the book Bauten, in which he openly

expressed anti-Semitic tendencies by denouncing the Jewish-Marxist

influence on German construction. On the role of architecture in the

reconquered east by the Nazis, Schulte-Frohline wrote: "We are fighting

for Germany, for the maintenance and recovery of the soul of our people,

which is mirrored most visibly in our craft and architectural

culture."

The

folowing year he joined the Nazi Party. His conservative,

traditionalist construction style shaped the housing architecture of the

Third Reich and thus represented the most significant influence of the

Stuttgart School on building under the Nazis. The Horst-Wessel-Halle

today, no longer with the Nazi eagle-mounted column as seen in the

period photo. Schulte-Frohlinde also belonged to the movement's ideology

as seen in his foreword to the book Bauten, in which he openly

expressed anti-Semitic tendencies by denouncing the Jewish-Marxist

influence on German construction. On the role of architecture in the

reconquered east by the Nazis, Schulte-Frohline wrote: "We are fighting

for Germany, for the maintenance and recovery of the soul of our people,

which is mirrored most visibly in our craft and architectural

culture." During the war,

Schulte-Frohlinde served as an officer in the Wehrmacht Air Force from

1939 to 1943. Initially deployed as a technical officer on the staff of

Combat Squadron 2, he led the staff squadron of this squadron as a

captain in 1940. He was shot down in the western campaign with his

Dornier Do 17Z and barely survived the crash landing about ten miles

southwest of Diksmuide, receiving the Iron Cross first class and was

promoted to major. During the First World War he had served as a pilot

in the Richthofen fighter squadron until the end of the war. .gif) On

the left is the former Reichsschulungsburg der NSDAP und DAF in a

period postcard and today, unchanged. In 1941 Schulte-Frohlinde was

appointed honorary professor of architecture at the Technical University

of Munich. Midway through the year he was relieved of his duties as

head of the DAF architects' office and from that point on he headed the

planning of the DAF's large-scale buildings in Munich. From 1943 to 1945

he took over the chair for architecture from German Bestelmeyer at the

Technical University of Munich and in the final phase of the war he was

appointed Gaudozentenbundfuhrer of Munich-Upper Bavaria. In the task

force for reconstruction, which met from 1943 under the direction of

Albert Speer, Schulte-Frohlinde was involved as an advisor and was

entrusted with planning the reconstruction of Bonn. In August 1944,

Hitler included Schulte-Frohlinde in the God-gifted list of the most

important architects. On Easter Sunday, April 1, 1945, a member of the

Freikorps Sauerland shot dead eight Soviet forced laborers in Erwitte.

On

the left is the former Reichsschulungsburg der NSDAP und DAF in a

period postcard and today, unchanged. In 1941 Schulte-Frohlinde was

appointed honorary professor of architecture at the Technical University

of Munich. Midway through the year he was relieved of his duties as

head of the DAF architects' office and from that point on he headed the

planning of the DAF's large-scale buildings in Munich. From 1943 to 1945

he took over the chair for architecture from German Bestelmeyer at the

Technical University of Munich and in the final phase of the war he was

appointed Gaudozentenbundfuhrer of Munich-Upper Bavaria. In the task

force for reconstruction, which met from 1943 under the direction of

Albert Speer, Schulte-Frohlinde was involved as an advisor and was

entrusted with planning the reconstruction of Bonn. In August 1944,

Hitler included Schulte-Frohlinde in the God-gifted list of the most

important architects. On Easter Sunday, April 1, 1945, a member of the

Freikorps Sauerland shot dead eight Soviet forced laborers in Erwitte.

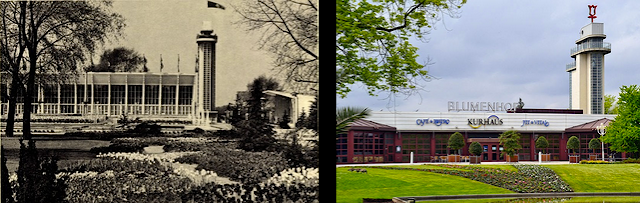

.gif) The Thingplatz shown here is centrally located in

front of a gymnasium and swimming pool as well as other sports

facilities near the shore. It served as a Freilichtbühne-

The Thingplatz shown here is centrally located in

front of a gymnasium and swimming pool as well as other sports

facilities near the shore. It served as a Freilichtbühne- .gif) Most

of the sculptures in Vogelsang – "Fackelträger" (torch bearer), "Der

deutsche Mensch" (The German Man), "Adler" (Eagle) and the

"Sportlerrelief" (sportsmen-relief) - were created by Willy Meller.

Whilst the wooden sculpture German Man disappeared in 1945, the

other two sculptures - partially damaged - are preserved today as seen

here. The torchbearer at Solstice Square is a five metre high,

martial-muscular figure of the Aryan "master race" to be bred according

to Nazi ideology. The raised torch refers to the ancient Greek myth of

Prometheus, who gives fire to man. It fits with the symbolism of light

popular in National Socialism and was reinterpreted politically: The

flame symbolizes the rebirth of the nation through the victory of

National Socialist Germany. The white area next to "Fackelträger" (torch bearer) covers up references to Hitler which originally read:

"Ihr seid die Fackelträger der Nation. Ihr tragt das Licht des Geistes

voran im Kampfe für Adolf Hitler." (You are the torch bearers of the

nation; You carry on the light of the spirit in the fight for Adolf Hitler.) The

architect of the monument was Clemens Klotz and the statue

itself was made by Willy Meller. On top of the monument a fire

could be lit.

Most

of the sculptures in Vogelsang – "Fackelträger" (torch bearer), "Der

deutsche Mensch" (The German Man), "Adler" (Eagle) and the

"Sportlerrelief" (sportsmen-relief) - were created by Willy Meller.

Whilst the wooden sculpture German Man disappeared in 1945, the

other two sculptures - partially damaged - are preserved today as seen

here. The torchbearer at Solstice Square is a five metre high,

martial-muscular figure of the Aryan "master race" to be bred according

to Nazi ideology. The raised torch refers to the ancient Greek myth of

Prometheus, who gives fire to man. It fits with the symbolism of light

popular in National Socialism and was reinterpreted politically: The

flame symbolizes the rebirth of the nation through the victory of

National Socialist Germany. The white area next to "Fackelträger" (torch bearer) covers up references to Hitler which originally read:

"Ihr seid die Fackelträger der Nation. Ihr tragt das Licht des Geistes

voran im Kampfe für Adolf Hitler." (You are the torch bearers of the

nation; You carry on the light of the spirit in the fight for Adolf Hitler.) The

architect of the monument was Clemens Klotz and the statue

itself was made by Willy Meller. On top of the monument a fire

could be lit..gif)

As might be expected, intellectual standards were very low and attendance to the Ordensburg did little to foster education. Students went to each of the four castles for a year at a time. At the academy at Krössinsee, the first year, the stress was on the study of racial science, athletics, boxing and gliding. Great attention was given to horse riding because that gave the Junkers the feeling of being able to dominate a living creature. The second year, at Sonthofen, the emphasis was on athletics, parachute jumping, mountain climbing and skiing. The third year, at Vogelsang, the students received political and military instruction, and physical training. One of the tests that year was the Tierkampf, combat with bare hands against wild dogs. The fourth year, at the prestigious Teutonic castle Marienburg, the Junkers were expected to obtain their final military formation, and political and racial indoctrination.On the left is the Malakoff then and now, the entrance to the Ordensburg. In February 2020, the German Alpine Club announced that it had taken over the left wing from Malakoff and would set up a club home there. Before this the Malakoff entrance building with the vehicle yard was sold to an Opel car museum, and the Degener brothers moved from Vreden to the Ordensburg with their Europe-wide largest collection of Opel vintage cars.